So, You Want to Influence a Foreign Government?

By: Dr. Douglas BryantPosted on March 15,2025

Article Date 01/04/2025

Messaging for competition and crisis

It is no secret that the Marine Corps wants to influence Russia, China, and other foreign governments. Like the rest of the Joint Force, the Corps is working to optimize information capabilities for competition and crisis—as described in the 2022 National Defense Strategy—to deter the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) aggression against the United States, Taiwan, the Philippines, and others. Washington is concerned with a host of other PRC behaviors—not least of which is its massive and continuous malicious cyber operations against U.S. critical infrastructure. But so far, the DOD has prioritized warning against the consequences of seizing Taiwan.

The clearest messaging has come from the top. More than once, President Biden publicly stated that the U.S. would intervene to defend Taiwan if the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) attacked.1 Deputy Secretary of Defense Hicks made clear that the Replicator Initiative is intended to counter China in a Taiwan Strait contingency, and ADM Paparo, Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, has said he wants “to tum the Taiwan Strait into an unmanned hellscape.”2

What effect, if any, do these messages have on Xi Jinping and his few trusted subordinates with any real power? Power matters here because the purpose of these messages is to change Beijing’s behavior, and thus, the intended message recipients must have the power to affect state-level behavior. Within the influence community, there is debate about how to answer that question and even whether it is answerable. The fact that there is an influence community suggests that most influence capabilities and operations are not so highly visible as declarations from combatant command (CCMD) commanders, deputy secretaries of defense, or presidents. Less visible and less potentially escalatory—but also less potentially effective—influence operations may produce smaller effects that are harder to identify.

Purported effects typically assume—rather than demonstrate—causal connections. The PLA is investing in countering unmanned aerial vehicle swarms; they must be responding to ADM Paparo and Secretary Hicks, obviously. However, the PLA has been researching and investing in creating and countering drone swarms for years. How do we know their latest research and development is not what they would have done anyway—or had even planned to do before those public comments were made?

The trouble with giving up on assessing the effects of influence operations is that without them, you cannot get better. You cannot learn anything, determine what works, what does not, what produces unintended consequences, or even whether your actions are undermining your own goals. The PRC’s wolf warrior diplomacy is a prime example. That overly aggressive, bullying style of international diplomacy almost entirely backfired. It was intended to force compliance with Beijing’s foreign policy, view of its borders, ownership of the South China Sea, and the reach of its economic leverage. Instead, it pushed South China Sea claimants, South Asian, Pacific, Central and South American, and African nations closer to the United States.

Given the time, tax dollars, personnel, and other resources invested in the Joint Force’s influence capabilities, failure to develop precision measures of those capabilities would be akin to fraud, waste, and abuse. So, it is worth asking some basic questions to understand what the influence endeavor is based on, how to determine if it works, and what kinds of outcomes one would expect it to produce.

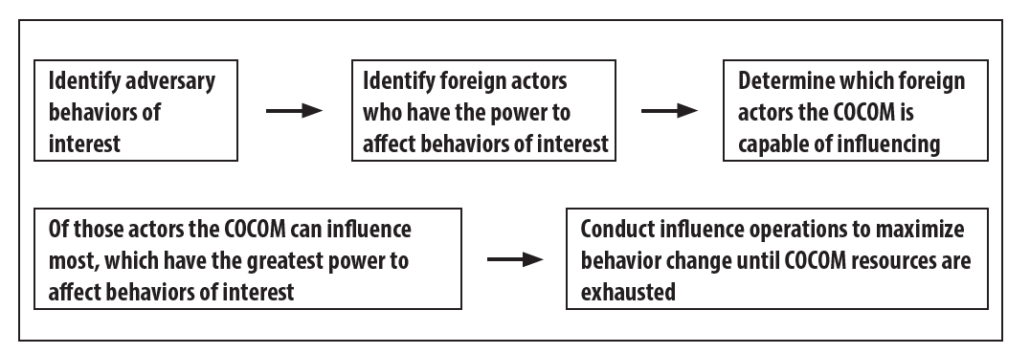

The first question the Marine Corps must answer is whether it can, in fact, influence any adversarial actors who meet two criteria: the actor is engaged in some behavior the Corps wants to affect, and the actor has the power to change that behavior. Behaviors of interest, to be more specific, can refer to intentions to take certain undesirable actions in the future (e.g., to invade or blockade Taiwan)—behaviors the influence specialist wants to change—or desirable behaviors the influence specialist wants to reinforce and maintain. In either case, these are typically state behaviors that express a nation’s foreign policy. When adversarial nations have autocratic regimes, the actors in question are a small number of national state, party, and military decision makers and the cadre of trusted advisors who can influence them.

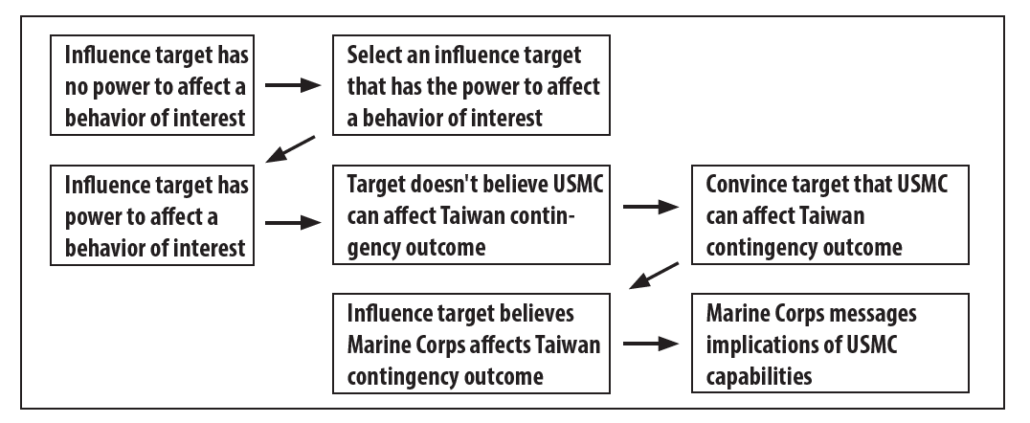

Like the rest of the Joint Force, the Marine Corps must identify these actors, which of them have the power to influence state behaviors of interest to the Corps and defense policies the Corps supports, and which of them—if any—care about and pay attention to the Marine Corps and its capabilities. The conclusion is not foregone. Beijing may be preoccupied with deep concern over Space Force, Air Force, and Navy capabilities. Of course, Beijing’s leaders could both discount the role and effectiveness of the Marine Corps in a Taiwan contingency and be mistaken in doing so. It could be the case that they discount the Marine Corps when in fact, given China’s goals and capabilities, Beijing should give due weight to the role of Marines in future combat. In this case, it would fall to the Marine Corps to reshape those judgments to garner greater influence.

Combatant commands, which have unique information capability authorities, face practical limitations that may prevent them from ever leveraging Marine Corps capabilities for information effects. Combatant command information staffs, J3Xs, and J39s have limited capacity. If they determine that adversarial leaders are most concerned with, and most responsive to, messages about air, space, and naval capabilities, they will prioritize those messages, perhaps justifiably excluding Marine Corps systems from influence messaging content.

Whether adversarial state actors care enough about the Marine Corps to change national policy and state behaviors is a straightforward intelligence question. If the intelligence community can answer it in the affirmative, the Corps then confronts whether, how, and who should carry out a campaign of influence.

Whether to take any specific national security action, or program of actions, is too big and important a question to address here. It requires fuller treatment. American history includes catalogs of actions taken because they could be—without due diligence of whether they should have been. Deterrence is the best justification for strategic information operations—influence with the goal of preventing warfare—so one might reasonably ask, “What is there to lose by trying to avoid war?” Executed in ignorance, though, deterrence efforts can make warfare more likely—as when demonstrations of advanced capabilities produce an arms race that makes accidents more likely.

There is a logical, commonsense process for how to proceed with influence operations, and a scientific process for how to make the endeavor successful. The former is straightforward. National security organizations like the Marine Corps and its subordinate commands have missions and directives from higher echelons. Some of these organizations have guidance and orders to influence adversaries’ behavior. These are likely the first units in the chain of command to have the subject-matter experts capable of answering the questions above—whether there are potential influence targets who can affect state, party, or military behaviors and whether those actors care about Marine Corps capabilities enough to be influenced by them. These subject-matter experts are intelligence analysts; linguists and cultural experts; experts on the PLA, CCP, and PRC organizations, structures, decision making, and policymaking; red teams; psychologists; other social and behavioral scientists; strategic communication experts; influence planners; and sometimes technical subject-matter experts.

The essential question above is whether there is a specific, individual human who both 1) has the power to change state behavior (or has influence on someone who has such power) and 2) can be influenced by a given U.S. command (given its specific capabilities and authorities). Every command, whether a Service headquarters or a CCMD, is limited by its authorities in who and how it can influence—and further limited by its influence capabilities. This latter limitation encompasses the

organization’s knowledge of the information environment, inclusive of its understanding of the specific individuals who could be influenced to some effect, together with its skill at wielding influence. Thus, there are more individuals who satisfy condition 1), who have the power to change state behavior (or influence someone who does), than there are who satisfy condition 2), who can be influenced by a given U.S. command.

This question is too rarely asked and more rarely answered. It is more often replaced with questions like, how can we influence China? or the PLA? or Russia? or only slightly better, PRC and PLA leadership? Worst of all, it is often replaced by the question how can we leverage the exercises and other activities we are already doing to influence unidentified individuals in these groups? Imprecise questions like these undermine measurement and refinement.

Of the skilled professionals listed above, then, two are key. Psychologists who know how to influence individuals and how to design and assess measurable influence operations, and intelligence professionals who gather and interpret the information on which psychologists rely.

Complementing the logical process is the scientific process used to test influence operations—in scientific parlance—to detect effects and measure effect sizes—and in military parlance—conduct assessments using measures of effectiveness. In doing this, scientific methods should be (but typically are not) employed to establish whether association, correlation, and causation are present. Such methods are key to ruling out alternative explanations by controlling for the influence of other variables and the influence of chance. To uncover relationships between independent and dependent variables, experiments must be designed (i.e., operations must be planned) using proven experimental design methods that can detect such relationships.

This is done by constructing operations as experiments that can disconfirm specific hypotheses. To take an example from above, one might hypothesize that ADM Paparo’s hellscape comment had some effect on Beijing’s behavior—but such a hypothesis is too broad to be disconfirmed. What the influence effects specialist wants to know is not whether Beijing responded to Paparo, used the word “hellscape” in its own public messaging, or even changed its behavior and claimed that it was doing so in response to Paparo—but whether, in fact, Beijing made a specific, desired behavior change—the change the operation was designed to bring about—in response to Paparo’s message, and that had Paparo not communicated his message, the behavior change would not have occurred.

To answer this question, the influence professional must have and investigate more specific hypotheses. Typically, these are formed when an operation is initially designed. Disconfirmable hypotheses—hypotheses that can be disconfirmed through empirical experimentation—in this case take the form, “Influence act a will cause influence target t to take response action r.” In practice, such a hypothesis is built on other hypotheses about groups of adversary actors (e.g., PLA officers with the power to affect cyber-attacks on U.S. critical infrastructure). Specific influence acts typically include specific messages, messengers, and contexts. They are delivered to specific target audiences to achieve specific behavioral outcomes. Specificity makes measurement possible. Imprecision in target audience identification (e.g., operations to influence “PRC” or “PLA”) muddies measurement and results in failure to demonstrate operational outcomes.

Through careful design, measurement, repeated experimentation, and data analysis, influence practitioners can—in theory—discover how to get foreign leaders to take desired paths, but those findings will usually be relative to the specific uses, leading to findings of the sort: Xi is movable on topics t1, t2, and t3, but not t4, t5, and t6. Xi is receptive to messages m1, m2, and m3 on topic t1, but not persuaded by those messages on topics t2 and t3. Message m1 is persuasive 20 percent of the time when delivered through messenger d1 and 31 percent when delivered by d2. Message m2 is only persuasive 22 percent of the time when delivered through d1, but d2 is effective 34 percent of the time with m2. Message m3 is a military action not delivered by a specific messenger, but it has proved 10 percent effective.

Neither the Marine Corps nor the DOD has such findings or the data on which to reach them—and that is not only because influencing foreign leaders is historically a State Department task. Currently, no one in the U.S. government has such data because no one has embarked on the whole-of-government research program necessary to produce it.

Whether the Marine Corps, DOD, and other government departments and agencies will develop the necessary data infrastructure and measure influence activities—rather than just doing things—remains to be seen, but neither current budgetary priorities, institutional inertia, nor the short tenure of American military and civilian leaders bode well for research-driven statecraft. On the plus side, advanced data capture and analytics for foreign influence may be tools too powerful for any government to wield responsibly.

>Dr. Bryant is a veteran Army Intelligence Officer, Psychologist, and Neuroscientist at Headquarters Marine Corps DC I where he works as an Information Operations Effects Specialist. He has written on institutional and policy challenges facing DOD’s information and influence efforts, and proposed solutions in Proceedings and the Journal of Information Warfare.

Notes

1. Frances Mao, “Biden Again Says US Would Defend Taiwan if China Attacks,” BBC, September 19, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62951347.

2. Jim Garamone, “Hicks Discusses Replicator Initiative,” DOD News, September 7, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/article/3518827/hicks-discusses-replicator-initiative; Joel Wuthnow, “Why Xi Jinping Doesn’t Trust His Own Military,” Foreign Affairs, September 26, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/why-xi-jinping-doesnt-trust-his-own-military.