Archibald Henderson: An Era

By: LtCol P.N. Pierce & LtCol F.O. HoughPosted on December 15,2024

Article Date 01/01/2025

>Originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette, July 1960. Extracted from Chapter Four of The Compact History of the U. S. Marine Corps, by LtCol P.N. Pierce and the late LtCol F.O. Hough. Copyrighted by Hawthorne Books, May 1960. $4.95

ON OCTOBER 17, 1820, MAJOR ARCHIBALD HENDERSON was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and became the fifth Commandant of the Marine Corps at the age of 37.

Under the blunt, outspoken Henderson the Marine Corps underwent some profound changes. The long span of years of his command were eventful ones, and through a series of dramatic events which commanded wide attention, the Corps established a high reputation with the people of the nation. The man who was to become known as “the grand old man of the Marine Corps” was largely responsible.

Morale was low in the Armed Forces of the 1820s. As usual after each war, the military had been shunted aside. The War of 1812 was rapidly passing into the limbo of forgotten things. It had been an unpopular war to begin with, as far as Americans were concerned. The war-torn era of Napoleon had ended at Waterloo, and the great powers of Russia, England, Austria and Prussia had combined in the Quadruple Alliance to “preserve the tranquillity of Europe” against a revival of revolution. The danger of being drawn into a European war appeared very remote. The Congress of the United States was much too occupied with internal expansion to pay attention to the relatively few people it hired for the defense of the nation. The strength of the Marine Corps stood at 49 officers and 865 enlisted men.

Immediately upon assuming command, Henderson, who had evidently given the matter considerable thought, set about improving the morale and efficiency of his Corps. He began by personally inspecting every shore station which included Marines and many of the ship’s detachments. He was a stickler for detail, and continually gave evidence of knowing thoroughly the job of everyone of his Marines. He insisted on the strictest economy in the expenditure of funds, and personally handled the majority of the Corp’s legal affairs. Although he had the reputation of being a martinet, he went to great lengths to insure that his officers and men were properly accorded their every right.

In the matter of training he was almost a fanatic. He had long realized that the key to the efficiency of any fighting organization lay in two inseparable and basic fundamentals—training and spirit. He ordered all the newly commissioned officers to duty at Marine Corps Headquarters, in order to personally supervise their indoctrination and training. During most of his tour of duty, the Army was unable to absorb all of the graduates of West Point. Henderson obtained as many of these officers as possible for the Marine Corps. To assist in the training of the new officers, and to act as a nucleus for a landing force, he kept a skeletonized battalion at Headquarters. This battalion was thoroughly trained in the latest developments of military weapons and tactics.

Henderson demanded, and received, the strict subordination of all his officers. He took no nonsense from anyone, including his superiors in the U.S. Navy. On one occasion, when the Navy Department countermanded his orders to a Marine Captain to go to sea, Henderson went directly to the President. He respectfully, and probably vigorously, explained that it was imperative that his orders be carried out in order to vindicate his position and authority. Four days later the captain in question reported for sea duty, and the Secretary of the Navy reported to the President for what might have been described as a unilateral conversation.

The agencies for maintaining law and order in the United States during the first half of the Nineteenth Century were few and far between. Those which did exist were poorly organized, and even more poorly trained. During this era the Marines were often called upon to lend a hand in local disturbances.

In the great Boston fire of 1824 they performed both rescue work and police functions in helping to stamp out the wave of pilfering and looting which followed the holocaust.

A short time later, Maj Robert D. Wainwright earned prominent mention in the classic school books of the era, McGuffey’s Readers. And, for the next 75 years, the nation’s school children received a lesson dealing with the heroic conduct of Marines.

The scene of the action was the Massachusetts State Prison at Boston. Having become thoroughly dissatisfied with their lot in life, some 283 prisoners staged a riot which rapidly got beyond control of the prison authorities. With the situation out of hand, the warden sent a frantic call for help to the Boston Marine Barracks.

Maj Wainwright, with a detachment of 30 Marines, soon arrived at the prison area. Making a hasty estimate of what was apparently a bad situation, Wainwright came up with a simple solution. Hastily forming a single rank facing the prisoners, he ordered his Marines to fire a warning volley into the air. The shots had the desired effect and the clamor subsided. As his Marines reloaded their muskets, the major addressed the rebellious prisoners, “These men are United States Marines,” he said. “They follow my orders to the letter.”

Turning to the Marines, Wainwright consulted his watch, and then issued his orders in a loud, parade ground voice, “Exactly three minutes from now I shall raise my hand over my head,” he bellowed. “When I drop my hand you will commence firing. You will continue to fire until you have killed every prisoner who has not returned to his cell.”

For three long minutes not a word was spoken. The only sound was the shuffle of the inmates’ feet as they dejectedly returned to their cells.

With the advent of the 1830s the traditional isolationist policy of America underwent an abrupt change. It had become apparent to the United States that many areas of commercial advantage lay beyond its own boundaries. This change in policy had a pronounced effect on the functions performed by Marines. As a result of it, the Marines, under the energetic leadership of their fifth Commandant, ranged far and wide to protect the interests of their country.

Late in 1831 the natives of Sumatra seized and robbed an American merchantman in the harbor of Quallah Battoo. This act of piracy resulted in the murder of several members of the crew. In retaliation the United States sent the frigate Potomac, especially outfitted for the job, on a punitive expedition against the Sumatran pirates. Arriving in February 1832, the Potomac put a landing force of over 250 Marines and sailors ashore. In two days of bloody warfare, the force captured four pirate forts and reduced the town of Quallah Battoo to a heap of smouldering ruins.

At the same time, on the other side of the Southern Hemisphere, Marines were having some difficulties in South America. Argentina was attempting to establish claim over the Falkland Islands. In pursuit of this claim, that country looked with extreme disfavor on American vessels conducting trade with the Islands. In an effort to discourage this practice, the Argentinians proceeded to impound three American schooners and jail their crews. Marines from the sloop Lexington waded ashore and through dint of considerable small arms fire, succeeded in impressing the Argentine officials that the United States did not look kindly upon such treatment of its ships and citizens.

But, as far as the Marine Corps was concerned, the most far-reaching effect of the new anti-isolation policy of the United States was reflected in the Act of 1834. Passed by Congress on June 30, the legislation authorized a substantial increase in the strength of the Marine Corps. It also settled the question of its control, by placing it in the hands of the Secretary of the Navy. In addition, it authorized the President to order the Marines into whatever action his judgment dictated, including duty with the Army. Within the year the President was to make good use of his newly granted powers.

In the Everglades of Florida a bad situation of long standing was rapidly coming to a head.

Over a period of many years runaway Negro slaves had found refuge with the Seminole Indians and many slaves and members of the tribe had intermarried. The southern planters, aware of this refuge for their escaped slaves, had made repeated petitions to the Crown of Spain, without avail. Unhappy with the refusal of Charles IV to take the necessary steps to return their slaves, the southern land owners began to petition their own government for the annexation of Florida. In 1819 a portion of Florida was purchased from Spain for $5,000,000. Immediately the slave owners renewed their demands to the government that their slaves be returned. Inasmuch as some 75 years had passed since their ancestors had taken refuge in Florida, it was a little difficult for the Seminoles to understand the claims of the planters. As a result, such demands met with a particularly unenthusiastic response by the Seminoles.

Under the political pressure eventually brought to bear by the slave owners, the Administration completed a treaty with the Indians, under which the government would take the tribe under its protection and assign the Indians to reservations. Perhaps things might have worked out if certain enterprising souls hadn’t become aware of the lucrative possibilities in the profession of slave catching. The “slave hunters,” in direct violation of the terms of the treaty, entered Florida in organized bands to catch runaway slaves who brought high prices on the slave markets. There is no evidence to indicate that the government made any attempts to stop this practice, although the Indians continually demanded redress.

In 1828 the proposal was made to the Seminoles to move to a reservation in the area now occupied by the state of Arkansas. Tribal chiefs made a reconnaissance of the area and returned with the report that “snow covers the ground, and frosts chill the bodies of men.” Their objections notwithstanding, the Seminoles were ordered to emigrate West. At which point, things got rapidly out of hand.

Determined to force the emigration, the government sent troops into Florida. Just as determined to remain where they were, the Seminoles made preparations for war. In December 1835 the hostilities began in earnest, and in a short time the horrors of the Seminole War were being chronicled throughout the land.

BGen D.L. Clinch, who was commanding the US troops in Florida, was charged with the responsibility of the removal of the Indians. The end of the year found the well-armed Indians, under the leadership of a colorful half-breed named Osceola, assembled in the almost inaccessible swamps of the Withlacoochee River.

Clinch, whose immediate problem was to protect the white settlers, decided to attack the Indians. Since his own force, which occupied Fort King near the present town of Ocala, was too small for the job, he sent to Fort Brooke on Tampa Bay for reinforcements.

The reinforcements, numbering 110 and under the command of a Maj Dade, answered the call of Gen Clinch with colors flying and bugles blaring across the swamps. With the possible exception of Custer’s debacle at Big Horn, the fate of this force is without parallel in the history of Indian warfare.

Shortly after Dade’s force crossed the Withlacoochee, they were met with an ambush so effective that only two survivors remained to crawl through the wire grass to safety. One was Pvt Clark of the 2d Artillery who, although badly wounded, is reputed to have crawled to Fort Brooke, a distance of 60 miles. The other was Louis Pacheo, a Negro slave who acted as guide for the force. There is reason to suspect that the escape of Pacheo from the ambush was something more than blind luck. Be that as it may the only man to survive without a scratch lived to the venerable old age of 95 without being taken to task for his treachery, if such it was.

On the same day as the Dade Massacre, Osceola and a small band invaded a dinner party given by Gen Wiley Thompson, who had been sent from Washington to oversee removal of the Indians, and murdered the General and his five guests. If there had been any doubts about the earnestness of the war in Florida, the Dade Massacre and the murder of Gen Thompson provided the clinching argument.

By the spring of 1836 the Army in central Florida found themselves in difficulty. Some 1,000 soldiers were trying to round up and deport over 3,000 Indians. The State militias, which had originally augmented the Army of the South, soon had their stomachs full of poor food, swamp fever and general discomfort. And, with the coming of spring, they left Florida for healthier climes.

To add to the general misery, the Creek Indians of southern Alabama and Georgia decided to go on the warpath. The results of this uprising were severe enough to cause the Army to shift its main effort from the Seminole country to the area occupied by the Creeks.

At this juncture Archibald Henderson volunteered the services of a regiment of Marines for duty with the Army. The offer was promptly accepted. On May 23, 1836, President Jackson, under the recently enacted law, ordered all available Marines to report to the Army. Henderson, never one to sit on the sidelines, insisted on leading the regiment personally. By taking practically all officers, reducing shore detachments to sergeant’s guard, and leaving behind only those who were unfit for duty in the field, Henderson was able to mobilize more than half the total strength of the Corps.

There is a tale, often related by Marines, that Col Henderson closed Marine Corps Headquarters during this period. It is said that he locked the door to his office, placed the key under a mat, and tacked a neatly lettered sign to the door which read:

Have gone to Florida to fight Indians. Will be back when the war is over.

A. HENDERSON

Col. Commandant

More reliable accounts indicate that the Commandant left the Headquarters in charge of LtCol Wainwright, with the Band to provide the guard. Among those deemed unfit for duty in the field was one Sgt Triguet, whom Henderson commended to Wainwright in a letter of instruction which began: “Sergeant Triguet is left to assist in attending to the duties at Headquarters. He is a respectable old man, and has no other failing than that which but too often attends an old soldier….”

Henderson, with a force of 38 officers and 424 enlisted men, reported to Gen Winfield Scott at Columbus, Georgia. Since the Commandant was under direct orders of the Secretary of War, he technically became an Army officer and was placed in command of a brigade composed of Marines, Army Infantry and Artillery, and friendly Creeks.

Presaging the modern Marine battle garb of dungarees, the troops wore white fatigues, rather than the green and white uniforms of the period. Armed mostly with muskets, they also carried some of the new-fangled Colt rifles which had a disconcerting tendency to explode spontaneously when carried loaded for any length of time in the hot sun.

Both the Marine commander and Gen Scott took an optimistic view of the final outcome of the campaign. In a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Henderson wrote: “It is now expected that the Campaign will be closed in the course of ten days or two weeks….” On the same day Gen Scott went on record to the effect, “war against the hostile Creeks is supposed to be virtually over.” One may well speculate as to the thoughts of Gen Scott a month later when he was recalled to Washington for an investigation of his conduct of the war against the Creeks and Seminoles. After a long, drawn-out investigation, Scott was exonerated and restored to his command.

The end of summer brought with it the termination of the Creek Campaign. The Creeks were removed to a reservation in what is now the state of Oklahoma, and the Army of the South again turned its attention to the problem of the Seminoles in Florida.

On June 24 a battalion of Marines under LtCol W.H. Freeman reached Milledgeville, Georgia, and moved on into Florida. In October Freeman’s battallion was consolidated with the one Henderson had been leading into a six-company regiment and moved to Apalachicola, to garrison Fort Brooke. The Marines were augmented by a regiment of Creek Indians, some 750 strong, who had been mustered and were paid as militia. The regiment was officered mainly by Marines, and wore white turbans to distinguish them from the enemy during battle. The Seminoles were rather unhappy about being pursued by their blood relatives, and showed their dislike by scalping all Creeks who fell into their hands.

On November 21 the Creeks, under the command of 1stLt Andrew H. Ross, fought an advance guard action at Wahoo Swamp. From Wahoo a four-pronged advance, two columns of Army troops and two of Marines, pushed the Seminoles back to the Hatchee-Lustee River. Six days later the main body of Indians was located in the area of the Great Cypress Swamp, and was promptly attacked. The attackers managed to capture the horses of the enemy and 25 prisoners, most of whom were women and children. The braves slipped back into the swamp. Henderson left a detachment to guard the prisoners and horses, while the regiment pressed on after the warriors who had taken up positions on the opposite bank of the Hatchee-Lustee. The troops extended along the river bank and took up a cross fire, in an effort to dislodge the enemy. As soon as the Indians’ fire slackened, the troops crossed the river by swimming and by means of logs. According to Henderson’s report, “… we pursued the enemy as rapidly as the deep swamp and their mode of warfare permitted.”

The chase continued until nightfall when Henderson was forced to withdraw his troops from the dense undergrowth. The result of the day’s operations was the capture of the Indian women and children, already mentioned, 23 Negroes, a few horses and some clothes and blankets. The battle report states that one Indian and two Negroes were seen dead by the troops.

As a result of his routing of the Indian forces Henderson was brevetted a brigadier general and several Marines were promoted for “gallantry.” Four days later, Abraham, a Seminole Chief, appeared at Henderson’s camp under a flag of truce. This marked the beginning of several days of negotiations between Maj Gen T.H. Jesup, to whom Gen Scott had relinquished command upon being recalled to Washington, and the Indian leaders at Fort Dade. These meetings finally resulted in an agreement by the chiefs to assemble their people for transportation to their new reservation. The peace treaty was formally signed on March 6. Jesup, believing the war to be over, began to discharge his volunteers.

On May 22, 1837, Henderson received orders to proceed to Washington. Taking with him all Marines except two companies, which totalled 189 officers and men, Henderson left Florida the next day.

On the night of June 2, Micanopy, grand chief of the Seminoles, and several of his lesser chiefs who had encamped with their followers near Tampa Bay, the port of embarkation, were abducted and taken to the interior. The next day a report was received from the troops south of Hillsboro that the Seminoles encamped in that vicinity had disappeared. These two incidents were the signal of the renewal of hostilities. Gen Jesup reported, “This campaign, so far as relates to the Indian emigration, has entirely failed,” and requested to be “immediately relieved from the

command of the Army.” The Seminole War was far from over.

For the next five years Archibald Henderson vainly tried to get the remaining Marines recalled from Florida. His appeals were met with refusal by the Secretary of War, who felt that the need for Marines in Florida was more pressing than the need for their return.

Jesup was finally relieved and realized what had been his burning desire since the beginning of the campaign—to join his family and spend the rest of his life on his farm. He was replaced by Col Zachary Taylor, who was soon promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

The campaign wore on and the possibility of success appeared more remote with each passing day. Osceola, who had been arrested while conferring with Gen Jesup, died in prison at Fort Moultrie in October 1837. The next year some 4,000 Seminoles made the move to Oklahoma, though many of them slipped away from the New Orleans concentration camps and returned to the Everglades.

The two remaining companies of Marines put in four more years of duty along the coast and around the keys of Florida with the Mosquito Fleet. From June 1838 to the summer of 1842, this array of half a dozen small vessels, two barges and 140 canoes was manned by 68 officers and 600 men. The Marines of the fleet numbered about 130, and for the first two years of operation were commanded by 1stLt George H. Terrett who, seven years later, was to lead the way into Mexico City.

The object of the Mosquito Fleet was twofold, to intercept communications between the Indians and small boats operating off the Florida coast, and to conduct amphibious sorties into the interior of the Everglades. The fleet operated successfully throughout the remainder of the campaign, and the Indians came to have great respect for the “sailor boats” as they called them.

In the summer of 1842 the Seminole War gradually waned, without formal cessation of hostilities and with neither side clearly victorious. The Marines returned north in July, well pleased to be relieved of what had been six long years of extremely dreary duty. In the final accounting, 61 Marines had given their lives in the Seminole Campaign. Over half of them had died from disease, and one unfortunate soul had departed the scene, dispatched by a friendly musket ball—“discharged by accident.” In analyzing the success of the campaign, one need only reflect upon the fact that the Seminoles still occupy the Everglades of Florida.

With the Seminole War a matter for the record books, Henderson again turned his attention to strengthening and developing the Corps. His efforts were aimed at keeping the Marines in a state of readiness for any emergency, domestic or foreign. The remainder of his career was distinguished by such important events as the Mexican War and Perry’s Expedition to Japan. Under his direction Marines virtually covered the globe. To protect Americans and their commerce with China, they stormed the forts of Canton during the great Taiping Rebellion. In the South Seas they splashed ashore to bring the rampaging Fiji Islanders to heel. In the jungles of Central America they made their first contact with the Republic of Nicaragua, which was to see the repeated return of Marines over the next three-quarters of a century. Along the Gold Coast of Africa the slave traders, on more than one occasion, felt the bite of a Marine’s bayonet.

For the 50 years he wore the uniform of a Marine, Archibald Henderson preached the gospel of strong leadership and constant readiness. At 74, he dramatically demonstrated that advanced age was no deterrent to practicing what he preached.

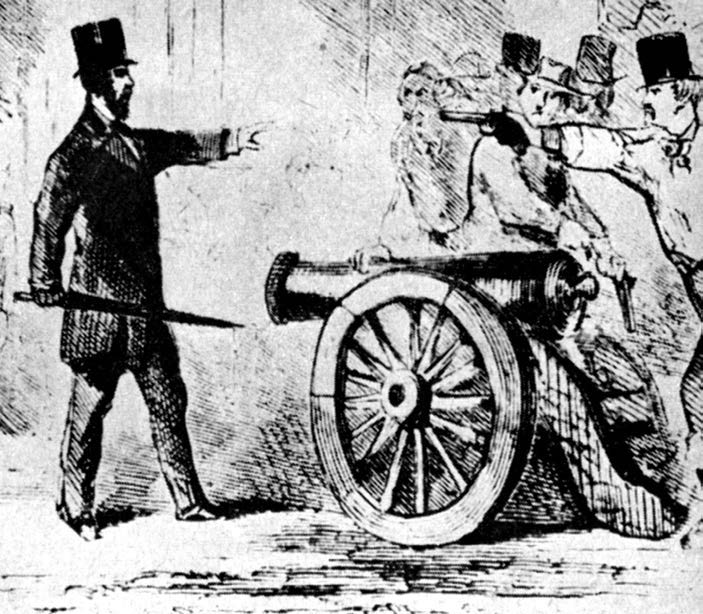

The issues of the elections of 1857 were particularly bitter ones. In an effort to control the election in Washington, the “Know Nothing” Party imported a gang of hired thugs, known as the “Plug Uglies,” from Baltimore. The gang commenced activities by physically threatening the voters, and finally put a complete halt to the elections by taking possession of the polling places throughout the city. Civil authorities, unable to cope with the situation, appealed to the President who ordered two companies of Marines from the Marine Barracks to restore order to the city.

The Marines met the “Plug Uglies” on Pennsylvania Avenue, in the vicinity of City Hall. The rioting thugs, who were armed with every conceivable weapon, dragged up a brass cannon, aimed it at the Marine formation and demanded that they return to their barracks. Capt Tyler, commanding the Marines, ordered a detachment forward to capture the cannon. At that moment, Gen Henderson, who had been mingling with the mob and was dressed in civilian clothing, walked calmly up to the muzzle of the cannon and forced the weapon around. Henderson addressed the “Plug Uglies,” warning them of the seriousness of their acts and telling them that the Marines would fire if it became necessary. In the hectic few minutes that followed, a number of rioters who fortunately were very bad marksmen, fired their pistols at Henderson. A platoon of Marines charged in to protect the Commandant and capture the cannon. One of the rioters, at point blank range, aimed his pistol at Henderson’s head. A Marine knocked the pistol to the ground with a butt stroke of his musket. The General promptly grabbed the culprit by the collar and the seat of his pants and marched him off to jail. With the riot getting out of control, the Marines opened fire. The rioters, suddenly convinced that the Marines meant business, beat a hasty retreat and order was restored to the city.

On January 6, 1859, the “grand old man of the Marine Corps,” who had served as Commandant under 11 Presidents, died in office at the age of 76. The impact of his strong personality and zealous devotion to duty remains to this day, indelibly engraved on the Corps to which he devoted over 50 years of his life.

The era of Archibald Henderson had encompassed two wars worthy of examination from the standpoint of the nation’s history. One, which had been purely internal, was the protracted campaign against the Creek and Seminole Indians. The other, which took place on foreign soil, provided the Marines with the first line to their hymn, and the nation with something it had long wanted—a western boundary that bordered the blue Pacific.