Force Design: Making the First Thing First – Logically

By: LtCol Noel Williams, USMC(Ret)Posted on April 15,2025

Article Date 01/05/2025

Design precedes development as the architect precedes the engineer

Force design is a critically important process for any military to ensure it is ready and able to preserve deterrence and meet the test of the next conflict should it occur. The Joint Staff defines force design as “a process of innovation through concept development, experimentation, prototyping, research, analysis, wargaming, and other applications of technology and methods to envision a future joint force.”1 Importantly, this definition describes force design as a continuing process of innovation; it is an infinite game.2

Currently, there is a great deal of attention on force design and modernization across the DOD given the rise of multiple peer adversaries.3 It has been especially prominent in the Marine Corps since 2019 when the 38th Commandant made it a centerpiece of his commandancy in his Commandant’s Planning Guidance. Given this Marine Corps focus on Force Design, and the author’s familiarity with these efforts, this article will use the Marine Corps as an exemplar to discuss force design processes and recommend force design best practices applicable to all components of the Joint Force. Thus, the subject addressed herein is the process of Force Design, rather than any specific instantiation of force design. The central idea is that Force Design is the logical first step of a larger force modernization process whose functions (force design, force development, force employment) must be performed concurrently and not sequentially as the current joint doctrine implies.4

Joint Force Development and Design and Historical Analogs

The CJCS Instruction 3030.01A, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design, outlines the processes and responsibilities for Joint Force Development and Design (JFDD) and describes three lines of effort: Build the force, educate the force, and train the force.

The Joint Operating Environment (JOE) document describes future challenges, providing a shared appreciation of the threat across the department. Developing this shared vision is foundational to all subsequent steps to build, educate, and train the force. For this reason, JFDD would be better described as threat-based and concept-informed vice the CJCSI 3030.01A formulation describing the JOE as setting the conditions “for effective concept-driven, threat-informed capability development for DoD.”5 Calling out distinctions between concept-informed/concept-driven and threat-based/threat-informed may seem overly pedantic, but the distinctions have significance beyond semantic nitpicks as will be discussed later. This is especially so in the case of the Marine Corps, whose force development process describes a “concept-based” approach that places even more emphasis on concepts than the CJCSI-prescribed “concept-driven” joint process.6

Whether the JFDD process is threat-based and concept-informed vice concepts-driven/-based and threat-informed is, in important ways, analogous to the early 2000s shift away from threat-based planning when Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld replaced this Cold War-era process with Capabilities-Based Planning (CBP).7 While it is true that JFDD-related concepts are developed using specific scenarios against specific adversaries, the subsequent reduction of these concepts to lists of concept-required capabilities as the next step in the JFDD process encourages these disaggregated data to be viewed and resourced as individual capabilities rather than a system of systems that has many interdependencies. The Joint Force is a system of systems, not a simple aggregation of collected parts, and thus requires a holistic system view when defining force designs and associated capability resourcing. A line-item view created by reductive textual analysis of concepts of varying quality and relevance yields lists of capabilities and gaps functionally equivalent to the now-discredited CBP.

An insightful 2015 article in U.S. Naval Institute News provided a

retrospective assessment of the shift to CBP fifteen years after its inception. The author explains the importance of the shift to CBP by contrasting it to the Army’s 1981 threat-based AirLand Battle doctrinal reset that was developed to counter the Soviet Union. The author explains how in CBP, the by-then moribund USSR was replaced by a generic near-peer threat that “has no connections to any geography, culture, alliance structure, or fighting methodology. That adversary has no objectives, no systemic vulnerabilities, and no preferred way of fighting. Instead, the enemy is a collection of weapons systems that we will fight with (presumably) a more advanced set of similar systems, in a symmetrical widget-on-widget battlefield on a flat, featureless Earth.”8 The article then describes how problematic such an approach is because it divorces force modernization from all the particulars necessary to develop the ways and means of a coherent system to defeat an adversary.

Geography always matters, as does weather, allies and partners, access, specific technical parameters of competing weapons systems, force posture, mobility, sustainment, and network resilience. The impact of the loss of these critical design considerations in the force development process was then amplified by two decades of focus on countering terrorism. This shift caused the department to lose focus on emerging peer threat ecosystems, even while entities such as the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Office of Net Assessment were warning about the challenges of a revanchist China.9

Additionally, CBP encouraged military planning to shift focus inward vice on the enemy, thus allowing institutional preferences to prevail over war-winning imperatives. In theory, CBP could result in a Joint Force that is so dominant that it overmatches any adversary with its superior technology and operational acumen, but in practice, this is not the case. Throughout this era, science and technology investments provided a patina of innovation, and while it did yield improvements in force protection against improvised explosive devices, the real focus of the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Services, and more importantly, the real money, was on developing the next better version of existing marque capabilities such as 5th-generation tactical aircraft vice uncrewed systems (drones, collaborative combat aircraft); better-towed tube artillery vice a healthy mix of self-propelled tube artillery, rocket artillery, and loitering munitions; geostationary military satellites vice large constellations of low earth orbit micro-sats, and large surface combatants vice a hybrid fleet incorporating uncrewed surface and subsurface vessels.

The most important contribution of the 2018 National Defense Strategy was the unequivocal shift back to threat-based planning. Subsequent joint doctrine such as CJCSI 3100.01 Series, Joint Strategic Planning System, CJCSI 5123.01 Series, Charter of the Joint Requirements Oversight Council and Implementation of the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, Manual for the Operation of the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, and the previously quoted CJCS 3030.01A all made improvements to how the Department approaches planning, requirements development, and solutions development. But, as with any complex process highly dependent for success on external factors, adjustments, and improvements must be continuous given the changing nature of threats, technologies, budgets, and strategies.

From Time-Sequenced to Logically Sequential, Temporally Concurrent

CJCSI 303.01A describes three timeframes from the present: Force Employment (0–3 years), Force Development (2–7 years), and Force Design (5–15 years). While it is obvious that any process takes time, and therefore emerging capabilities will manifest further in the future than employing today’s forces, the three epochs described in the CJCSI are unhelpful and potentially detrimental.

First, the Russo-Ukraine war has demonstrated that such a time-specific process cannot work. Forces must be designed and redesigned in important ways in the near future, and the inability of a force to do so means defeat.

Second, at the most fundamental level, this sequenced construct fails. Logically, Force Design comes first (architectural design), then the force is developed to fit the design (like a house is built to an architect’s blueprint), and then it is employed (like a house is lived in). The underlying logic of the Joint Staff’s tripartite timeframes is that the acquisition process takes time and therefore Force Design manifests in the most distant epoch. But if we care about what we need to do to win tomorrow, we must focus on Force Design first just as someone building a house hires the architect before hiring the home builder.

The forces being employed today were subject to force design in the past, but in most cases, the too-distant past, and this is why there is so much consensus in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Congress on the need for acquisition reform.10 It is also inordinately focused on traditional long-term program acquisition when, increasingly, opportunities exist for software upgrades to existing systems and the purchase of more advanced non-developmental capabilities (e.g. FPV drones) is possible.

It is critical that designers, developers, and operators maintain a continuous dialog to ensure healthy feedback loops for rapid adjustment to processes and plans. The current time-dependent characterization serves as an implicit segmentation that discourages interactions among designers, developers, and operators and thus compromises essential feedback. Too often, combatant commanders (CCDR) and operating force emergent requirements are diminished by force designers and developers because these components are “just focused on today.” In the past, there was some justification for this argument, given the glacial evolutionary trajectory taken by all Services, but it is simply not true today. The CCDRs and forward-postured operating forces are increasingly conversant in both current and future adversary capabilities. In the past, when adversaries were decades behind us in fielding capabilities, a CCDR asking for contemporary countering capabilities was to ask for incremental changes; this is not the current circumstance. Now, when forward-postured forces ask for capabilities to counter existing and near-term adversary capabilities, they are asking for capabilities that are often far in advance of currently planned capabilities in the acquisition pipeline. This makes all the difference and is a key reason why the joint doctrine on timing and sequencing needs to be re-examined.

Concept-Driven or Concept-Informed

In describing the execution and implementation of JFDD, CJCSI 3003.01A states, “Concept-driven, threat-informed, capability development begins with a vision of the future operating environment that guides the DOD through a campaign of learning to identify the capabilities required to achieve the objectives established in national strategic guidance.”11

Concepts are extremely important elements of Force Design, but they are not the first thing, nor are they the most important. Vision comes first, and since force development processes and the systems they produce are sensitive to initial inputs, flaws in vision can have cascading negative effects on final outcomes. It is important to get the first thing, the main thing, right first. As Einstein said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask, for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.”

Force Design is more deductive than inductive (as a recursive intellectual exercise, it will inevitably have elements of both). Experience and professional judgment allow us to have a vision and then a hypothesis. This tentative vision, which describes the desired attributes of the future force (objective force) needed to solve a specific military problem, is the vital spark of creation: the first thing.

Concepts are useful because they pull together desired attributes into a coherent whole that describes important elements of the larger warfighting system and aids the progression from an impressionistic vision to the refined blueprint.

Current concepts are of varying quality and utility. They are certainly useful but also quite imperfect. Given this reality, basing Force Design on these concepts cannot help but lead to a flawed force design if we use textual analysis of these concepts to determine requirements per the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development Systems. Deconstructing concepts to transliterate them from conceptual think pieces to mechanistic lists, and then by rote, converting these lists to gaps and then requirements, is bound to lead to confusion amongst force developers and solution developers as the logical warp and woof of force design are shorn from the process, just as CBP did in the early 2000s. Additionally, flawed concepts do not get better through abstraction.

Of course, lists can be quite useful, but we do not need a concept to generate a list. It would be surprising if the authors of concepts did not start with a list in their minds first and there is nothing wrong with this. Concepts are useful for their consilience of information into a narrative that can deliver shared wisdom while also stimulating further creative thought.

The problem with lists is what bureaucracies do with them. They are often an excuse to reduce a complex cognitive task into manageable parts, which can be useful, but this is not a way to build a fit-for-purpose war‑

fighting system—it is simply a way to understand an already formed system. An architect does not take a pile of materials and build a house from what is in the pile. An architect uses education, experience, and knowledge of materials to build a plan. Mechanical engineers add greater detail to the blueprint to describe its internal systems and piece parts. If force designers are the architects, then force developers are the mechanical engineers, and both should be informed by concepts, not an abstracted list of those concepts’ key points.

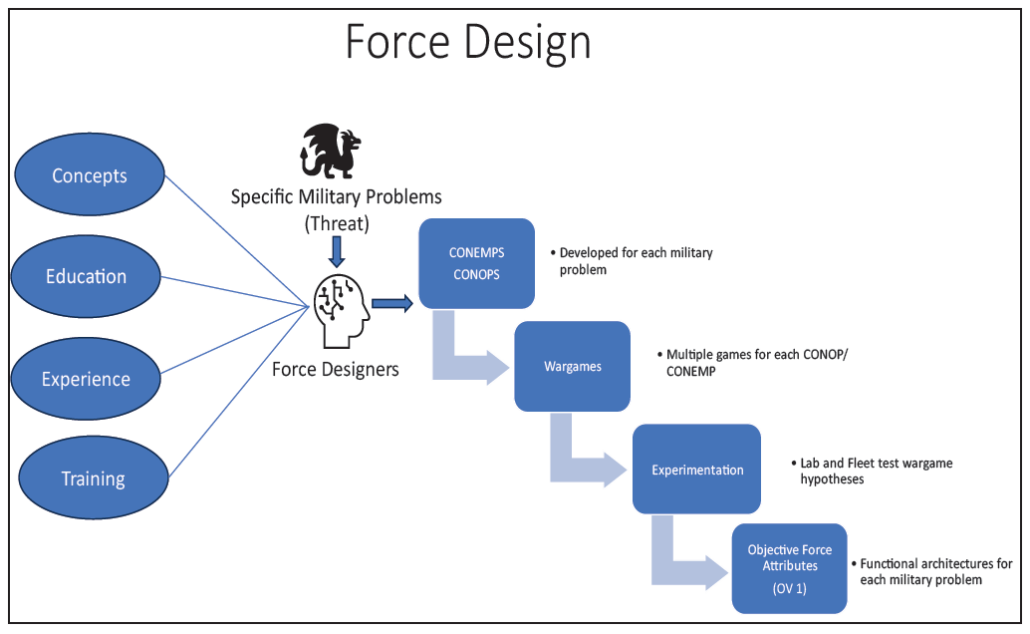

Figure 1 offers a notional process flow for Force Design while emphasizing the centrality of the force designer and his cognitive processes.

In sum, Force Design should be concept-informed and not concept-driven. Force designers produce conceptual frameworks for force developers to define system particulars—not simple lists.

The most valuable conceptual work is derived by focusing a concept on a very specific scenario believed to be likely. This requires concept developers to understand more than good storytelling and understand applied warfighting. If we were to develop a range of concepts/concepts of operation for all supported combatant commands across the spectrum of competition and conflict, we would possess a robust playbook for likely challenges at the level of detail necessary to describe and build a system. Critically, this approach would require articulation of not just material requirements but also non-material requirements such as training, organization, facilities, logistics, tactics, techniques, and procedures, etc.

A concept supports thought and creativity and loses its purpose when subjected to Derridean deconstruction. Force designers are architects, while force developers are mechanical engineers, and both use concepts to maintain the purpose of and vision for the objective force.

Those involved in Force Design should be informed by the complete range of concepts relevant to their military problem and focus on using this knowledge to develop the concept of operations in narrative form and graphically in an operational view.12 This ensures a systems view that maintains priority for a functional warfighting system versus the current process’s proclivity for devolution into a “one-to-N” list of preferred capabilities with no guarantee they will cohere into a functional warfighting capability that can be fielded. Such lists are also susceptible to manipulation at various levels of the chain of command by those advocating for their special interests whether part of the system architecture or not.

Case in Point: Marine Corps Force Design

A system comprises three fundamental elements: a purpose or function, system elements, and interconnections. In current process parlance, this is analogous to mission, capabilities, and interdependencies. This means Force Design is about system development—a combat system.

While biological evolution demonstrates that chance combinations of chemicals and energy can lead to complex lifeforms, we should not expect a warfighting system to emerge from the muck and mire of lists, technology, and capabilities, given that acquisition processes are, thankfully, somewhat shorter than biological evolutionary time horizons.

To achieve speed of relevance, we must rapidly create a system, test it, modify it, and test it again. Fortunately, military professionals have the benefit of specialized knowledge, which, when combined with past and ongoing Force Design efforts, enables them to jump ahead evolutionarily to an imperfect but fully formed vision for a future war‑

fighting system through deductive reasoning. Conversely, over relevant time horizons, gaps and capability lists will not coalesce into an objective force (system of systems) inductively—an overarching vision is required because we are looking for something new, unencumbered by traditional approaches and existing capabilities. A creative step of system definition, through Force Design, is required to guide force development.

Because the Marine Corps has evolved incrementally since World War II, there has been little attention paid to Force Design as the focus of the combat development process of this era was on buying a newer version of existing platforms. Force structure changes during this period were the subject of a parade of force structure working groups, force organizational review groups, and integrated process teams, with many of their recommendations not being implemented due either to lack of resources or to subsequent redirection from leadership.

This historical experience demanded little in the way of force design and mostly required finding ways to improve existing capabilities, such as a better truck, HMMWV, AAV, etc. For decades, the Marine Corps Combat Development and Integration Command (CD&I) focused predominately on the ground combat tactical vehicle strategy because that is where Service-defining capabilities were thought to lie, and except for aircraft, it was where the most expensive platforms resided.

Unfortunately, this was to the exclusion of upgrading our artillery systems to move beyond towed artillery to self-propelled. There was also inadequate investment allocated to Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance, and installations. There was substantial discussion about this, but funding was subordinate to the vehicle strategy. These decisions placed the Marine Corps in a situation where organic sensing and fires were inadequate for peer conflict. The 37th Commandant, Gen Neller, recognized the problem in his 2017 Posture Testimony, which stated unambiguously that “the Marine Corps is not organized, trained, equipped, or postured to meet the demands of the rapidly evolving future operating environment.”13

Force design must be a core competency for any organization charged with force modernization and development, or we will find ourselves in a circumstance, yet again, where Gen Neller’s testimony will ring true. Currently, the Marine Corps’ combat development organization (CD&I) lacks dedicated force designers and instead relies upon ad hoc process teams, study groups, and organizational reviews to produce the vision and the attributes for an objective force. This lack of dedicated force designers all but guarantees that the nuances of the proposed design developed by an ephemeral ad hoc group will be inadequately translated and implemented by force developers, having been lost in the translation from vision to concept to list.

Recommendations

Amend Joint and Service Process Documents

Both the order and the temporal descriptions in the CJCSI should be reconsidered to reflect the logical progression of force development: Force Design, Force Development, and Force Employment. In addition to changing the order of activities, the arbitrary timeframes should be eliminated as they are not accurate and simply reinforce the flawed conception that Force Design only manifests in the distant future. As discussed, this is no longer the case in an environment where software-defined capabilities and commercial, non-developmental solutions are an ever-increasing portion of the warfighting system.

Joint doctrine should make explicit that force design is threat-based and concept-informed vice concept-driven and threat-informed, and reemphasize the centrality of the JOE and related threat assessments. Threat documents should be unambiguously defined as the starting point for Force Design.

Force designs must be consistent with the Analytic Working Group principles and standards wherein they must be detailed enough to be tested through wargames and experimentation. Thus, force designs can be thought of as testable hypotheses. Importantly, the joint doctrine is explicit that wargaming, experimentation, and analysis are crucial to shaping Force Design. These activities do not validate a design; rather, they contribute to an iterative process of improvement. For the Joint Force, the Joint Warfighting Concept guides organization, training, and equipping, and Service designs should clearly reflect how they fit within the Joint Warfighting-informed Joint Force.14

Best Practices

Concept required capabilities derived from concepts are insufficient for force development purposes. As CJCSI 3030.01A states, “CONEMPs are the most specific of all military concepts and contain a level of detail sufficient to inform the establishment of programmatic requirements.”15 Thus, even with the existing joint doctrine, Force Design derived from operating and functional concept required capabilities is inadequate. If lists are made to aid in understanding and communicating, they must be placed in context and not allowed to become the main thing.

The Army has a force management occupational specialty (FA 50) that encompasses force development, force integration, and force generation. Officers are selected for FA 50 around their eighth year of service to attend a fourteen-week qualification course, and are expected to pursue subsequent education throughout their career.16 The Army also has a Futures Command headed by a four-star general in Austin, TX. The Marine Corps has made no investments in focusing and professionalizing its future force to the extent the Army has, and the results speak for themselves. The Army is implementing the fundamental aspects of Marine Corps Force Design (formerly Force Design 2030) at speed and scale and, one might argue, beating the Marine Corps at its own game.17 Of course, from a non-parochial perspective, the Army’s successes should be celebrated as they are making the Army more capable and relevant for the future fight. Go Army! All Services should learn from the Army and consider professionalizing the force design and force development workforce.

Force Design Professionals

Force Design is not a product, it is a process—a creative process, and it is the first step in force development once threats and challenges have been identified. At the outset of the Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030, this first step was performed by an ad hoc group because there was nobody dedicated to force design. Given this lack of force design professionals, when the Provident Stare (the name given to the initial Force Design 2030 planning group) organization was handed off to the Deputy Commandant CD&I, CD&I had to proceed over subsequent years with a continuing string of ad hoc integrated product team efforts focused on pieces of the overarching design developed during Provident Stare. This structurally exposes the process to discontinuities and confusion given the lack of continuity in those doing the design and development. If Force Design is a continuous process and not a one-off effort, then Services should all have dedicated force designers educated, trained, and experienced in the art and science of designing a force. Gen Berger and other senior leaders recognized that existing capability portfolio management processes were suboptimal for a design effort requiring discontinuous change given they are the product of the historical, incremental approach to force development.

Given Force Design’s centrality to force development, and the inherent need for continuous adjustment, force design should be an organic core competency.

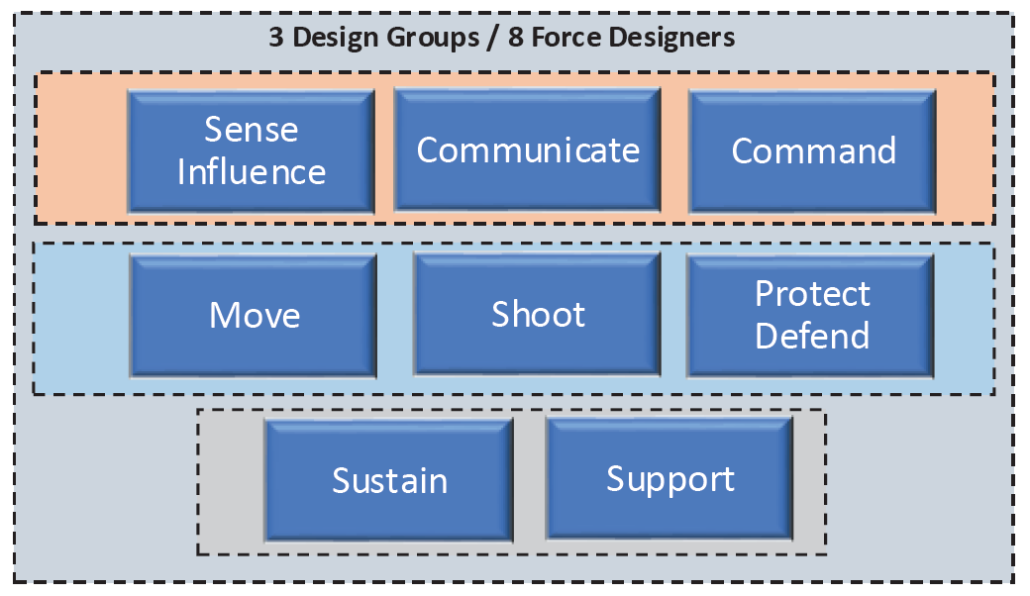

In the Marine Corps, this could be accomplished by converting existing capability portfolio managers (CPMs) (active-duty colonels) to force designers. Force Design focus areas might include sense/influence, communicate, command, move, shoot, protect/defend, sustain, and support, each overseen by a force design colonel (Figure 2). As an option, these elements could be grouped into design groups should a different rank/command structure be desired. These design groups would be configured as follows:

- Knowledge (K-DG): Sense/Influence; Communicate; Command.

- Fight (F-DG): Move; Shoot; Protect/ Defend.

- Enable (E-DG): Sustain; Support.

Alternatively, rather than form separate design groups, the aforementioned groupings could simply be viewed as “caucuses” amongst the force designers, which in practical terms could be used to plan travel and briefings when all force designers cannot attend or should other reasons so dictate. Such an informal grouping could enhance synergy between force designers that have especially strong interdependencies.

All relevant domains would be addressed in each of the design groups with the biggest difference being that Aviation would be fully integrated, versus the special relationship that now exists between CD&I and Deputy Commandant for Aviation (DCA) where the Aviation CPM is effectively a liaison for DCA vice an integral part of the requirements process. Currently, DCA determines requirements and provides solutions to the Aviation CPM. If deemed necessary, an aviation-focused design group could be added, but other CPMs would still approach their design activities in all domains, including air. The multidomain battlefield requires force design that is conceived in all domains.

For the Marine Corps, the criticality of naval integration suggests that adding a Navy captain as a ninth force designer would be beneficial. This individual would provide connectivity to OPNAV staff and Numbered Fleet Headquarters. Given the current direction of the Army, an Army force designer would also be a logical addition, and a SOCOM force designer would be helpful as well.

Force designers would work together daily as an integrated team like the civilian concept of scrum where a multi-disciplinary team works together to produce a new product. Battle rhythm and daily routine would be very similar to the Marine Corps’ School of Advanced Warfighting with research, seminars, and supporting analysis culminating in the development of a blueprint for the Objective Force, a narrative description of the doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, and facilities attributes of the envisioned force. A supporting brief would be available to general officers and others to ensure consistent messaging on the desired Marine Corps of the future.

On a yearly cycle, all operating and functional concepts would be briefed by the owner or author of each respective concept. This would reinforce concepts as a major component of Force Design’s intellectual foundation. Guest speakers from National Defense University, Marine Corps University, and local think tanks would be regular calendar events.

Travel to exercises, experiments, wargames, other Service Futures Commands and force design entities, and industry partners would occur monthly. Force designers need to be imbued with a sense of the possible through extensive outreach to operating forces, other Services, industry, and academia. The Marine Corps Warfighting Lab would provide regular updates on insights drawn from their wargaming and experimentation activities.

Force Developer Professionals

Force development follows force design and is guided by a Force Design blueprint. Marine Corps Deputy CPMs could be redesignated as force developers. The current senior/subordinate relationship between CPMs and deputy CPMs could continue with the new force designer/force developer construct since close coordination will be required to translate the force attributes described in the Force Design blueprint into formal requirements or problem statements (for problem-based acquisition). Force developers would run the Capabilities-Based Assessment process.

Force developers would focus exclusively on requirements and problem statement development. Solutions would best be accomplished by solution developers under a single roof to benefit from multi-disciplinary expertise and enhanced situational awareness given the proximity and integrated processes within a separate solutions directorate. Force developers would work in close coordination with solution developers to continually refine requirements while force development and solution development benefit from creative tension caused by the clear separation of responsibilities. This increased specialization also allows more time for each to perform their respective tasks.

Notionally, force developer portfolios would map directly to the eight force designer portfolios and would address the following:

- Sense & Influence: Intel, C-Intel, Cyber, all domain sensors, space, information.

- Communicate: Space, terrestrial, military/commercial C4.

- Command: Command Relations, Authorities, Componency, Joint/Combined integration.

- Move: Ground, air, and sea mobility.

- Shoot: Air, ground, lethal, non-lethal, kinetic/non-kinetic, cyber.

- Protect/ Defend: Air, ground, cyber.

- Sustain: Organic and theater logistics.

- Support: Ground, Air, Sea installations, war reserves, supply, maintenance.

Solutions Development Professionals

For the Marine Corps, solution development is done within multiple organizations including the Combat Development Directorate, the Warfighting Laboratory, Systems Command, and Training and Education Command, among others. Solution refinement would be an iterative process involving structured interactions between requirements and solution developers. Over time, a separate solution-focused directorate, headed by a senior executive or brigadier general, would develop a cadre of solutions professionals who understand Joint Force, industry, and technology opportunities and will be equipped to steer solutions through the optimal acquisition pathway.

Conclusion

As stated above, Force Design is first and foremost an act of creation. It involves the assimilation of historical and personal experience, missions, threats, technologies, concepts, concepts of operation, strategic guidance, Joint Force concepts and capabilities, and especially CCDR (customer) demand. The cognitive assimilation of multi-variate and complex knowledge to derive a coherent system capable of performing desired functions is where systems thinking and force design thinking coalesce into a vision of an objective force.

As a continuous process, Force Design requires dedicated force designers to adapt designs in response to changing threats and opportunities. Each Service has an advanced career-level school for operational planning like the Marine Corps’ School of Advanced Warfighting. A force design division within CD&Is Combat Development Directorate would provide an analogous environment to develop Service-level strategic planners and prepare colonels for increased responsibilities as general officers serving as deputy commandants and in commands such as the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab and Marine Corps Systems Command and various joint assignments. The traditional ad hoc approach to the assignment of senior leaders worked in an era of incremental change, but the increasing complexity of the modern battlefield and the associated technical aspects of capabilities development require a more professionalized approach to senior leader talent management.

While not the focus of this article, force development processes beyond the CBA process should be explored to streamline and speed up the development of requirements and the crosswalk of requirements to a dedicated Solutions Directorate that maintains an initial bias toward joint solutions.

While the foregoing recommendations, in their specifics, are focused on the Marine Corps, the fundamentals of force design and force development are applicable across the department:

- Force development should be threat-based. The JOE and related threat assessments are the foundation upon which force development is conducted.

- Force development should be concept-informed. Concepts are important narratives that describe pieces of the overarching warfighting system, but they are, by design, tentative and not comprehensive.

- Force design, force development, and force employment are concurrent, not sequential, processes.

- Force design is a creative mental process accomplished heuristically—it is not a dissection of capabilities described in incomplete and evolving concepts. Concepts are just one input among many.

- Joint Capabilities Integration Development System needs to be benchmarked against a conflict like the Russo-Ukrainian War and its ability to deliver a hellscape-like set of capabilities as defined by COMINDOPACOM, ADM Paparo. If it cannot deliver against these tests at the speed of relevance, it should be replaced.

Force Design is the locus of innovation and the architect of force development; we must evolve our processes and organization and professionalize the force design workforce to do it well.

>LtCol Williams is a Fellow at Systems Planning and Analysis and provides strategy and policy support to the Deputy Commandant, Combat Development and Integration.

Notes

1. Department of Defense, CJCSI 3030.01A, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design, (Washington, DC: October 2022).

2. James Carse, Finite and Infinite Games (New York: Free Press, 2013).

3. Congressional Research Service, Defense Primer: Geography, Strategy, and U.S. Force Design, (Washington, DC: December 2024).

4. CJCSI 3030.01A, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design.

5. Ibid.

6. Headquarters Marine Corps, Force Development System User Guide, (Washington, DC: April 2018).

7. Donald H. Rumsfeld, “Transforming the Military,” Foreign Affairs, May 1, 2002, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2002-05-01/transforming-military.

8. Col Michael W. Pietrucha, “Capability-Based Planning and the Death of Military Strategy,” USNI News, August 5, 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/08/05/essay-capability-based-planning-and-the-death-of-military-strategy.

9. Thomas Mahnken, Net Assessment and Military Strategy (Amherst: Cambria Press, 2020).

10. Government Accountability Office, DoD Acquisition Reform: Military Departments Should Take Step to Facilitate Speed and Innovation, (Washington, DC: December 2024).

11. CJCSI 3030.01A, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design.

12. Department of Defense, DoD Architecture Framework Version 2.02, (Washington, DC: August 2010).

13. Senate Committee on Army Forces Posture of the Department of the Navy, “Statement by General Robert B. Neller before Senate Committee on Army Forces Posture of the Department of the Navy,” June 15, 2017, 115th Congress.

14. CJCSI 3030.01A, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design.

15. Ibid.

16. Department of the Army, Dept of Army Pamphlet 600-3-25, Force Management Functional Area, (Washington, DC: April 2024).

17. Jen Judson, “US Army Deploys Midrange Missile for First Time in Philippines,” Defense News, April 16, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2024/04/16/us-army-deploys-midrange-missile-for-first-time-in-philippines