By June 15, 1944, the Central Pacific drive of the United States had inexorably pushed the Japanese back toward their homeland. Throughout the methodical island-hopping campaign, the Japanese had put up stiff resistance, fighting furiously on the sea, on land, and in the air. Unlike the Marines, who had developed a combined arms team that included infantry weapons, artillery, and tanks as well as naval gunfire and close air support, the Japanese failed to integrate all their available weapons. Noticeably absent was any significant use of tanks or armor. That would all change with the invasion of the Mariana Islands.

The 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions landed on Saipan on June 15. Japanese artillery and mortars were hidden on the heights overlooking the beaches. Small, local counterattacks attempted to push back the invaders. But the Marines’ combined arms teams dealt with each piecemeal attack. Despite more than 3,000 casualties and gains of less than a mile inland, in some places less than three hundred yards, the Marines had a solid foothold on the island. By evening, the Army’s 27th Infantry Division was landing.

On D-day, the men of Lieutenant Colonel William K. Jones’ 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, came ashore on the extreme left flank of the invasion force. Known as “Willie K” by Marines, Jones led his men inland beyond the beaches, where the bulk of enemy forces were entrenched, passing a radio station with its tall tower a few hundred yards from the beach.

The Japanese use of tanks on the first day was disjointed and uncoordinated. At about noon, four unsupported light tanks attacked the boundary between 1st and 2nd Battalions, 6th Marines. “Amtanks,” Marine amphibious infantry support vehicles mounted with a cannon, destroyed three of the Japanese tanks.

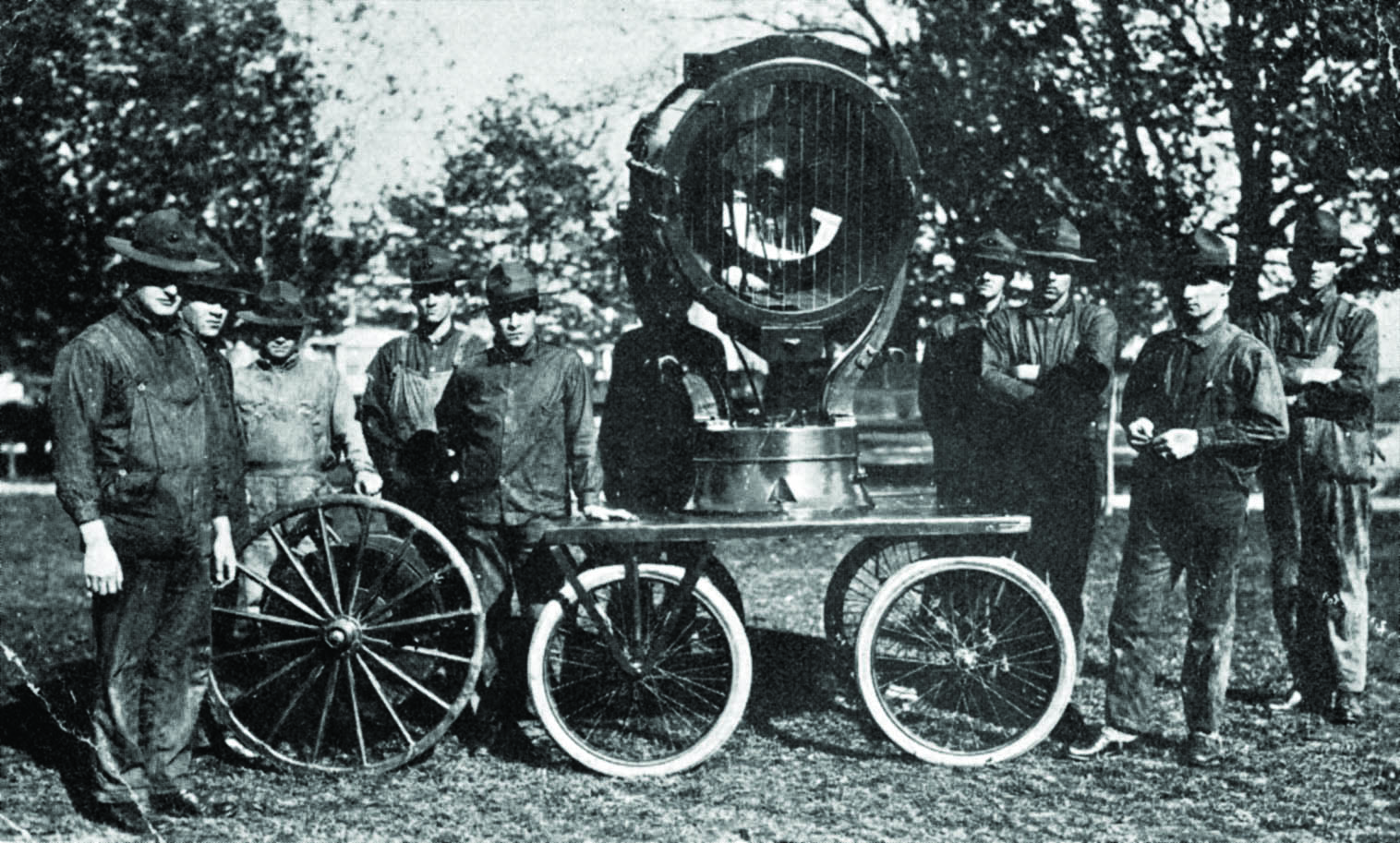

During that first night, Japanese sailors attempted a small landing with a few amphibious tanks on the left flank of 2ndMarDiv. It was defeated by the combined arms of the Marines, in part due to a new weapon, the 2.36-inch rocket launcher, which would later be nicknamed the bazooka. The Japanese also carried out frequent infantry attacks that night, probing and pushing for weaknesses to exploit. Artillery, naval gunfire, tanks and 75mm guns mounted on halftracks supported the Marine infantry, and by morning there were over 700 Japanese dead near 2ndMarDiv and hundreds more in 4thMarDiv’s sector.

The next day, Jones’ battalion continued to carve out the island’s terrain, flanked by 2/2 under Major Howard Rice. The men of 1/6 made way for the remainder of the 2nd Marine Regiment to land.

That night, both Marine divisions formed tight perimeters and prepared for a Japanese counterattack. Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saito, the commander of the Japanese army on Saipan, issued an order for the 136th Infantry Regiment and the 9th Tank Regiment to “attack the enemy in the direction of Oreal (Charon Kanoa Airfield) with its full force.” In “Saipan: The Beginning of the End” by Carl W. Hoffman, Saito described the plan: “The tank unit will advance SW of Hill 164.6 after the attack unit [the infantry] has commenced the attack. The tank unit will charge the transmitting station and throw the enemy into disorder before the penetration of the attack unit into this sector.” Then, the Japanese 1st Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force would attack from the north, parallel to the beach, to capture the Charon Kanoa Airfield, which was well behind Marine lines. One Japanese NCO noted, “Our plan would seem to be to annihilate the enemy by morning.”

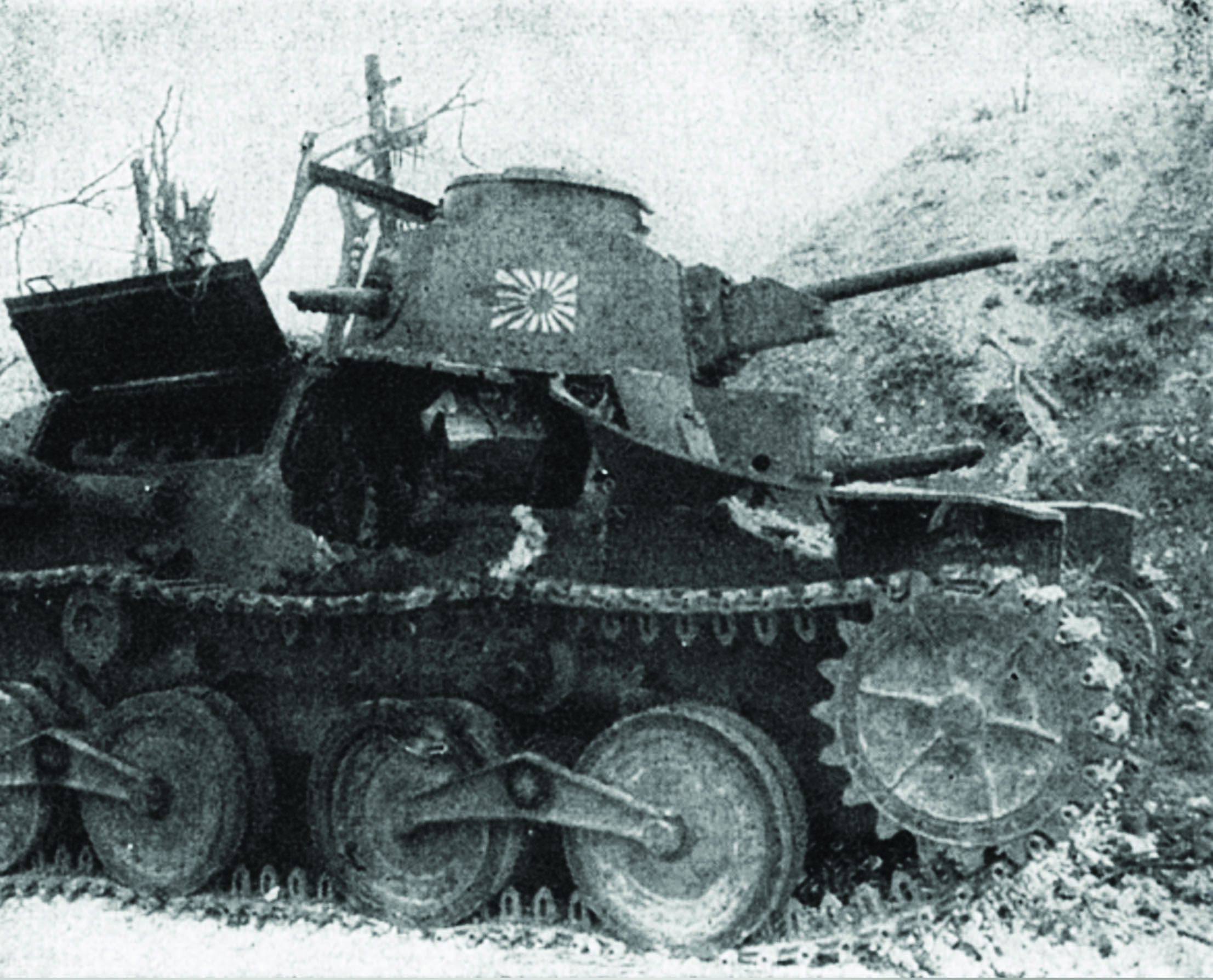

This time, the Japanese had between thirty and forty tanks. Most were medium Type 97 Kai Shinhoto Chi-Ha vehicles armed with a 47mm main gun and a couple of machine guns. A few were the smaller Type 95 Ha-Go armed with a 37mm main gun and two machine guns.

The tanks gave away their presence moving into their attack positions. The Marines heard the sounds of their engines, as well as the chanting and shouting of Japanese infantry, early in the evening. Due to poor coordination, the Japanese attack didn’t begin until 3:30 a.m. and the Marines were ready.

Captain C.G. Rollen called for armored support as the enemy tanks approached the front line of Company B, 1/6. A platoon of M4A2 tanks from Company A, Second Tank Bn, and a section of the halftracks were dispatched to support the infantrymen. Rollen called for artillery and naval gunfire support. The Navy provided an almost constant supply of star shells, turning the night into an eerie bright daylight.

Correspondent Robert Sherrod, in his book “On to Westward,” quoted one Marine who said: “The [Japanese] would halt, then jump out of their tanks. Then they would sing songs and wave swords. Finally, one of them would blow a bugle, jump back into the tanks, if they hadn’t been hit already. Then we would let them have it with a bazooka.”

Major James A. Donovan Jr. executive officer of 1/6, noted: “Many of the tanks were ‘unbuttoned,’ [with their turrets open,] the crew chief directing from the top of his open turret. Some were being led by a crew member afoot. They seemed to come in two waves, carrying foot troops on the long engine compartment or clustered around the turret, holding on to the handrail. Some even had machine guns or grenade throwers set up on the tank.” Marine artillery and machine guns stripped away their infantry support. Then the infantry Marines took over.

The armor of the Japanese light and medium tanks was so thin that, in many cases, Marine antitank rounds went completely through them. Several Japanese tankers became disoriented as star shells and tracers lit up the darkness. They strayed into nearby swamps and were immobilized, making them easy targets for the Marines.

Donovan recalled, “The battle evolved itself into a madhouse of noise, tracers, and flashing lights. As tanks were hit and set afire, they silhouetted other tanks coming out of the flickering shadows to the front or already on top of the squads.” Marine infantrymen hunkered down in their foxholes as some of the enemy tanks managed to reach the front-line positions.

Jones related in a June 1988 Leatherneck article, “One tank, leaking oil heavily, soaked a Marine as it passed over his foxhole. Another Marine, also lying low in his foxhole until a tank passed over him, jumped out and stuck a coconut log in its bogey wheels. The tank spun in circles. And when the bewildered tank commander opened his turret top to see what was going on, the Marine jumped on top and hurled a thermite grenade into the open turret. The tank blew up like a volcano.”

As the battle grew in ferocity, Rollen was injured by the concussion of a near miss. Jones ordered Captain Norman K. Thomas, the Headquarters Company commander, to take over the command. Oddly enough, Thomas had earned a Silver Star on Tarawa in relief of Rollen there. Now, as Thomas advanced, he was struck and killed by fire from a Japanese tank. Sergeant Dean Squires saw the captain fall. He shot the Japanese vehicle commander and placed a demolition charge on its back deck—the resulting explosion disabled the tank.

Corporal Donald Watson threw two phosphorous grenades on the back deck of a tank passing by his foxhole, then shot the crew as they exited the burning vehicle. Despite machine-gun fire from another tank, he retrieved a wounded comrade who was stranded in the midst of the enemy tanks. He would be awarded the Navy Cross.

Two other Marines were awarded Navy Crosses by knocking out seven tanks with seven rockets. Private First Class Charles D. Merritt and PFC Herbert J. Hodges moved into the open, dodging from left to right and back again. Both were untouched by enemy tank and infantry fire.

Private Robert S. Reed used his rocket launcher to hit four Japanese tanks. After he ran out of rockets, he mounted a Japanese tank and put it out of action with a grenade down the hatch. PFCs John Kounk and Horace Narveson stalked the enemy tanks. Ultimately, they scored hits on three tanks with four rockets.

Machine-gun squad leader, Sergeant Alex Smith, frustrated that the bullets of his guns bounced off the tanks’ armor, left his Marines and moved into the open. Using the grenade launcher mounted on his carbine, he disabled three tanks in quick succession.

Japanese artillery attempted to silence the Marine artillery instead of concentrating on the Marine front-line positions. This let the infantry Marines concentrate on the enemy assault. Marine artillerymen suffered many casualties but continued firing.

During the action, Donovan noted, “The Japanese tanks … appeared confused. As their guides and crew chiefs were hit by Marine rifle and machine gun fire, what little control they had was lost. They ambled in the general direction of the beach, getting hit again and again until each one burst into flame or turned aimless circles only to stop when hit.”

As daylight spread across the battlefield, Marine tanks and halftracks advanced into the area, finishing off many of the derelict enemy vehicles. By 7 a.m., the attack was over. Only one Japanese tank remained in action, but it rolled away into the hills. A call for naval gunfire brought down a barrage of 5-inch gunfire from a destroyer, which turned the tank into a smoking pyre. Despite the long night, Jones’ Marines began the day’s attack at 7:30 a.m.

If all the claims of destroyed tanks were added up, including those of the infantry, antitank guns, tanks, and halftracks, they would have equaled over 50 tanks. After the battle, 2ndMarDiv observers counted 31 metal carcasses. Perhaps a thousand Japanese men were dead. Jones was circumspect, stating that if the Japanese attack on June 17 had been successful, it “would have been fatal to the division’s fighting efficiency.”

For the rest of the campaign, Japanese tanks were used only in small numbers, the largest armored attack occurred on June 24, when tanks of Co C, 2nd Tank Bn, destroyed seven Japanese tanks near the town of Garapan.

Slowly, relentlessly, the Marines and soldiers conquered the island. Airfields were secured, allowing B-29s to bomb Japan. The only major counterattack was a banzai charge on July 7, the largest in the Pacific Island campaigns, of 4,000 bedraggled Japanese soldiers, sailors, and civilians without armored support. They smashed through front-line positions but were ultimately killed. The campaign for Saipan ended with the island declared secure on July 9.

In Oscar Gilbert’s book “Marine Tank Battles in the Pacific,” the commander of the Marine tanks, Captain Ed Bale, talked about credit for the destruction: “The argument has never been settled who destroyed the Japanese tanks, whether B Company [2nd] Tank Battalion or whether Weapons Company, 6th Marines did.” Sherrod gave credit to the infantrymen in an article for Leatherneck: “But most of the [Japanese] tanks were knocked out by infantrymen … who declined to get panicky. They waited in their foxholes until the moment was right, then they let go with bazookas or with antitank grenades. Some of them sat in their holes until the tanks rolled over and past them. Then they aimed at the weaker rear armor.” Ultimately it was the individual Marine, acting as part of the combined arms team, that defeated the Japanese in the Pacific.

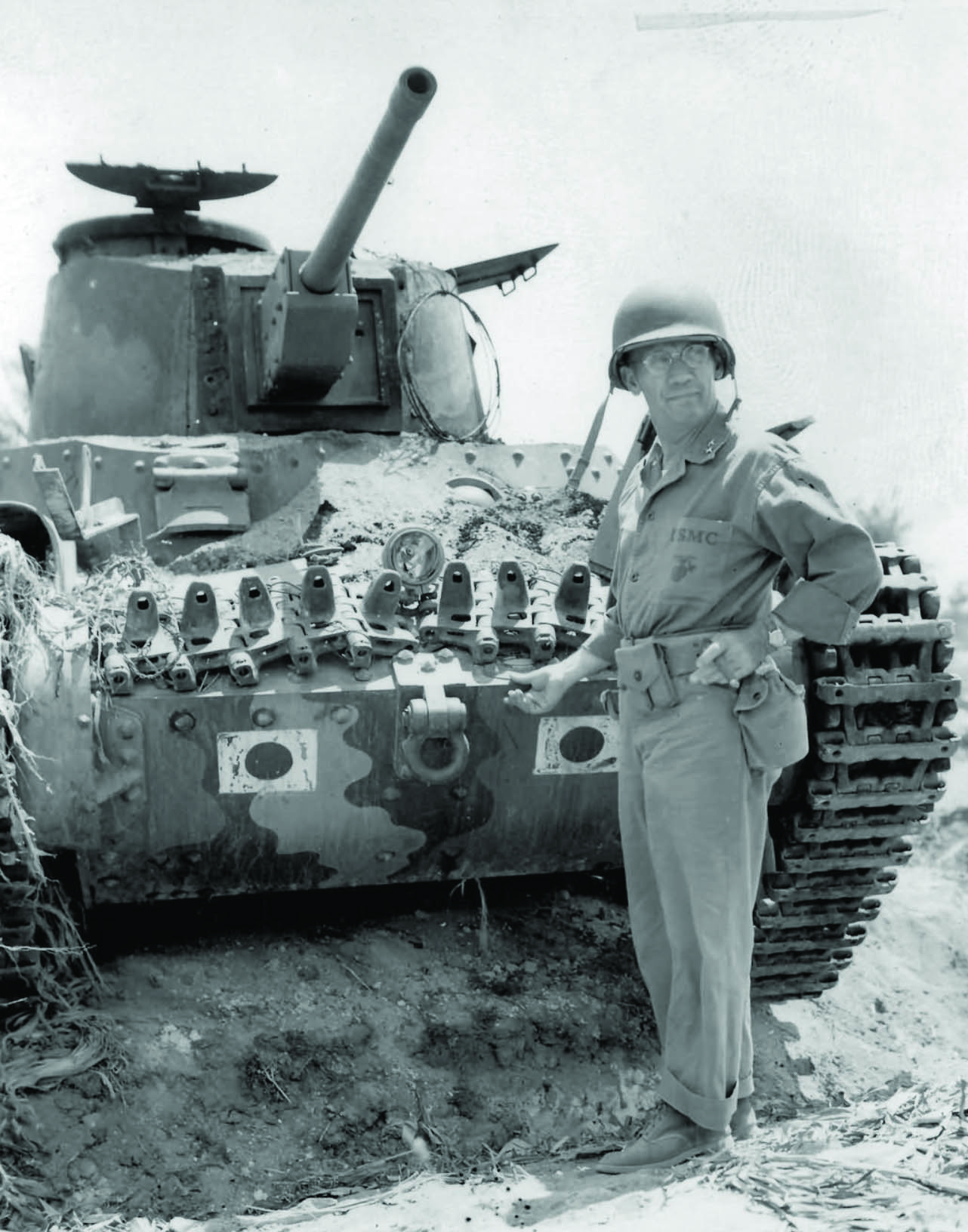

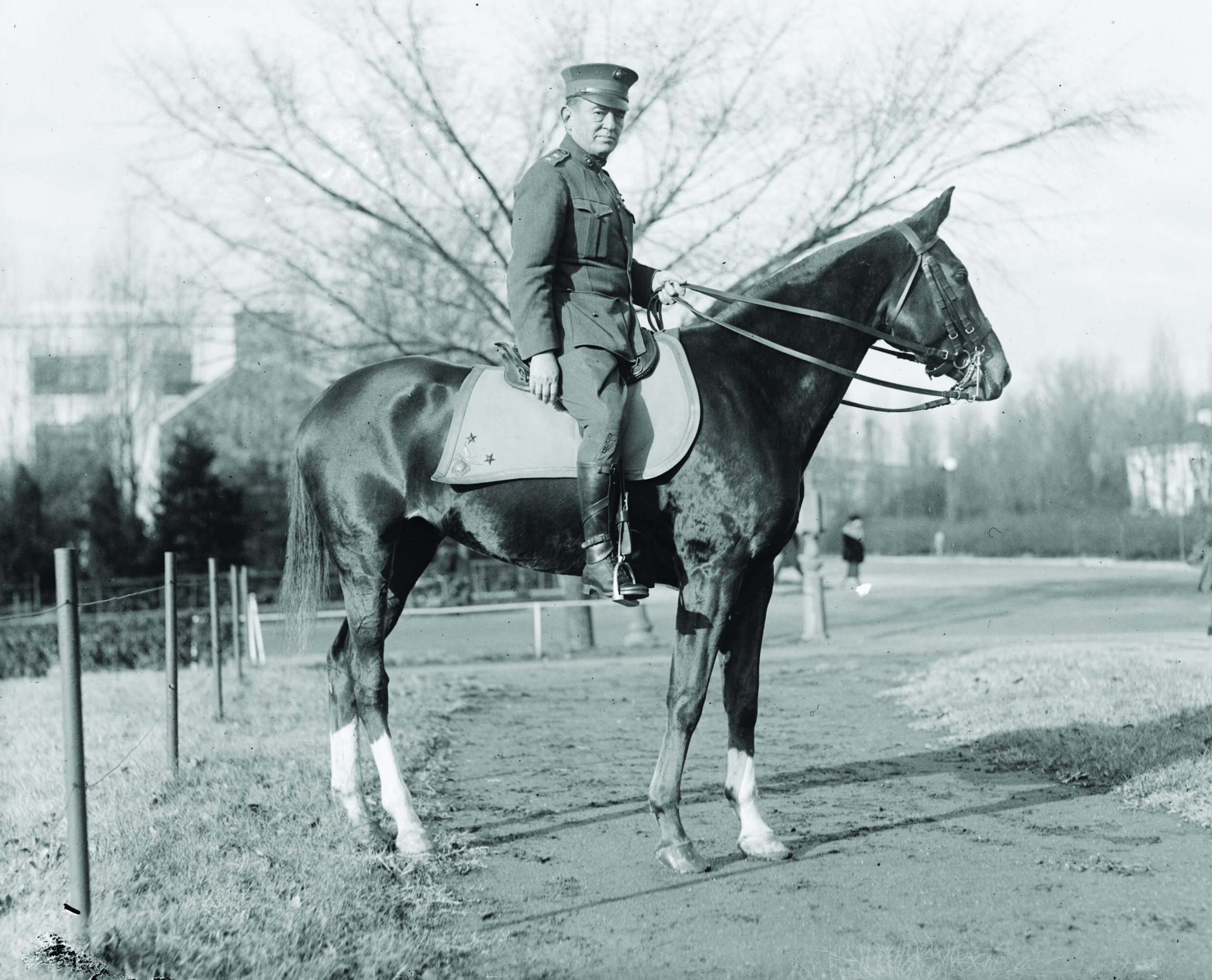

General Thomas Watson, commanding general of 2ndMarDiv, surveyed the destruction around 1/6 and pronounced, “I don’t think we have to fear [Japanese] tanks anymore. We’ve got their number.” The general was right; the Japanese never tried a large-scale tank assault in the Pacific.

Author’s bio: MSgt Jeff Dacus, USMCR (Ret) is a retired Marine tanker. He is the 2020 recipient of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation General Roy S. Geiger award. He is the author of the books, The Fighting Corsairs: The Men of Marine Fighting Squadron 215, Desert Storm Marines: A Marine Tank Company at War in the Gulf, and Perceptions of Battle: George Washington’s Victory at Monmouth.