A Furious Fight: An Artillery Marine’s Account of the Assault on Iwo Jima

By: Andrew BiggioPosted on February 15, 2024

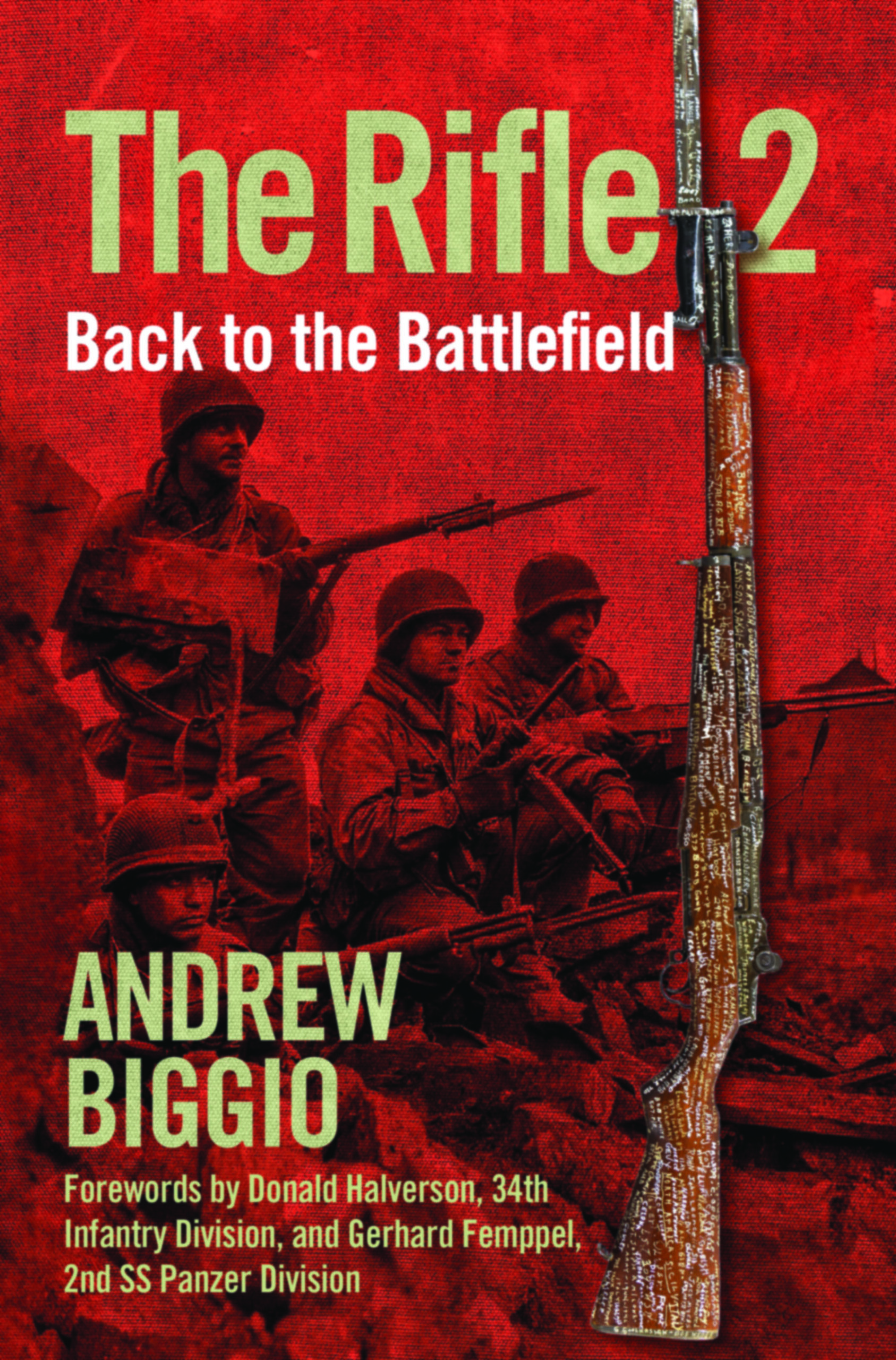

Editor’s note: The following story is an excerpt from the book “The Rifle 2: Back to the Battlefield” by Andrew Biggio. When Biggio returned from deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, he had questions about the cost of war, so he decided to ask those who knew the answer—World War II veterans. Marines like John Trezza, whose story we published here, told Biggio about the complexities of life after combat. The book can be purchased at https://amzn.to/47lUNs2. You can listen to a few in-depth conversations I had with Biggio on the Marine Corps Association podcast, “Scuttlebutt,” www.mca-marines.org/scuttlebutt.

The sounds of explosions and distant gunfire were fierce. There was no such thing as a break during D-day on Iwo Jima, and since there was no rear echelon, the battle raged everywhere. The call for fire missions was constant, but the men of “Fox” Battery, 2nd Battalion, 13th Marines, had no choice; they had to pause. “Our guns were red-hot. If we put another shell in through the cannon, we risked killing our whole gun crew,” John Trezza told me.

John Trezza stared at his 75mm howitzer. It was glowing red. You could have cooked hamburgers for the whole company on it. If another shell was placed into the artillery piece it could detonate. The Marines from his battery had just run a hundred shells through it in a short period of time. The Japanese had emplacements everywhere on Iwo. There was no end in sight to the calls for fire missions. They were facing an entrenched enemy estimated to be over 20,000 strong.

Casualty collection points and rendezvous areas developed behind the artillery units on Feb. 19, 1945, throughout the day. Wave after wave of Marines landed, and those who were supposed to be in reserve found themselves hitting the island midday on D-day instead of in the following days, as they’d initially supposed would occur.

Packs and supplies of those killed on the island began to pile up behind Fox Battery. Then one pack arrived that seemed to hush the sounds of distant gunfire as the Marines passed it around. Written in black ink on a piece of gear attached to the pack was the name “BASILONE.” The Marines of Fox Battery studied it in disbelief.

“When it got to me I couldn’t look at it,” said John, as he sat on a couch 77 years later. He was still emotional about the Italian-American war hero from New Jersey who had been killed in action. The two had much in common. They were both Italians, both Jersey boys, both Marines, and most of all, both proud Americans. John Basilone was admired by the whole Marine Corps after his actions on Guadalcanal, actions which had earned him the Medal of Honor.

“Before we left Hawaii, I got the chance to meet him. We all looked up to him. He didn’t have to go back into combat. He had a ticket to stay home forever and sell war bonds. He wanted to be with the Marines and he died doing so,” John added. It was amazing to see the profound impact Gunnery Sergeant Basilone still had on his Marines nearly eight decades later. These Marines were not 18 years old anymore. Here was 96-year-old man still upset as he remembered the loss of a Marine Corps icon. This was deep admiration. No propaganda could accomplish this. Gunny Basilone was truly a legend.

Back on Iwo Jima, an 18-year-old John Trezza couldn’t look at his fallen hero’s empty pack. It would be admitting that Basilone was really gone, and that the Japanese could kill anyone. Yet John’s turmoil over seeing Basilone’s gear was soon interrupted. It was time to start shelling again. The infantry depended on it.

John’s fatigues were powdery white, his uniform crusted by the salt from the ocean in which he had been submerged only hours before. His landing on the beach had been anything but pleasant. For all the Marines of the 5th Division, it had been hectic.

The entire 5th Marine Division was created for the purpose of taking Iwo Jima. It was the first time the Marine Corps developed such a unit with one island as its objective. John trained on Camp Tarawa in Hawaii for six months, then loaded onto the troop transport ship. It was there he met Medal of Honor recipient John Basilone. They and the other Marines aboard spent 38 days on the ship, heading generally west. After landing, the two would never meet again, yet John would never forget him. Iwo Jima affected the lives of all Marines who took part for generations to come.

After a long month of zigzagging through the Pacific, the 5thMarDiv anchored near the island of Saipan. The Marines took to the decks of the transport ships. “We would watch the B-29s take off to do their bombing runs. It seemed like there was one taking off every minute,” John said. This activity gave the Marines something to occupy their time, and the young men crowded the decks to view the mighty Army Air Corps fly away to strike Japan.

What they didn’t yet know was that those same B-29s were most likely being used in an attempt to prevent the onslaught that lay ahead for the 5thMarDiv. But aerial carpet bombing of the volcanic island of Iwo Jima proved to be unsuccessful. Saying the Japanese were a “well-entrenched enemy” was an understatement. Their tunnels, caves, pillboxes, and artillery emplacements remained for the most part unscathed despite American bombing raids. Anything that could be moved was wheeled or pushed into a tunnel or cave. The only advantage the bombings gained for the invading Marines was to provide defilades for cover. Other than that, Iwo Jima was like every other island, a smoky flaming mess with thousands of Japanese soldiers at the ready.

After a few days the ships left Saipan, destined for their final stop: Iwo Jima. “It was Feb. 19, a Monday morning, I’ll never forget it,” John said, shaking his head.

Before the sun rose, Marines were pushing their way through chow lines in the ship’s mess hall. It was noisy and hectic, and adrenaline was high. The first waves of Marines made their way to the bottoms of their ships. The ship carrying John’s unit was an LCT (landing craft tank). Stored inside the ship’s hull were amphibious tracs and DUKW (pronounced “duck”) boats that could be launched from the bow once the ramp opened. Overhead, fighter planes soared, providing covering fire for the first waves of Marines heading for the beach. The landing crafts and amphibious vehicles of this first wave chopped forward in the ocean until they reached the black sand.

“The first wave was unopposed. The Japanese wanted them to make their way inland to a certain point before opening up on them,” John explained.

“Which wave were you?” I asked.

“Third wave,” he replied. “All hell broke loose on the second wave.”

It was John’s turn to load onto the DUKW boat. “There were four of us. A Coast Guard guy was driving it,” he recalled.

The DUKW is a boat with wheels extending underneath it. It does not travel fast on water, as John and the other Marines quickly found out.

John recalled the frightening ordeal. “We were drenched with water within minutes of leaving the ramp of the big ship. Mortar shells were landing on each side of us.”

Landing crafts were also taking direct hits not far from John’s DUKW. The ocean seemed to be crowded with burning, scuttled landing crafts. The immense enemy fire, now concentrated on the beach and ocean, was causing a traffic jam for incoming waves of troops. The Coast Guard skipper in charge of John’s DUKW boat couldn’t find a place to land on his designated area of the beach.

The beach was littered with vehicles and Marines. The pileup was proving to be deadly and prevented reinforcements from coming ashore. The DUKW boats’ skippers were all having trouble finding openings, and when they did they risked running over Marines already present and bogged down by enemy fire.

The Coast Guard skipper of John’s DUKW boat had to work fast. He powered the boat to the far left of the designated area. “He led us right into a cove,” John said.

The DUKW boat full of scared Marines made its way into the natural opening. As it pulled into the cove the Marines began to jump off the sides.

“I jumped off the back and nearly drowned.” Unbeknownst to John, the water here was significantly over his head. In a sheer panic, he unslung his rifle from his body. His M1 Garand sank to the bottom of the ocean. Stripping himself of his gear, John rose to the surface, gasping for air. The DUKW boat was still within arm’s reach.

“I grabbed hold of it and climbed back on,” he recalled. The incident still left John feeling short of breath 77 years later.

John boarded the boat again. “I had no helmet, no weapon, no nothing!” The DUKW boat spun about, trying to find a spot where John and the others could place their feet. The skipper was able to locate solid earth for John to step out on. John waited for the thumbs-up, then was off.

“I ran as fast as I could to the beach. When I looked up I saw a 300-foot cliff. ‘Should I go up there?’ I thought. ‘What’s on the other side?’ I figured I would go back to where I was supposed to land first, Red Beach One.”

John began to follow the beach farther down before making his advance inland. “I was running around bareback, with no equipment whatsoever!” John was practically shouting as he related this to me in his living room. The extreme circumstances of his landing had lost none of their shock value over the years.

Nervous and unarmed, John scurried along the black sand. “I got to Red Beach 1 and there was still no possible way to get in. I don’t know how all those guys got into that little pass,” John said. Red Beach 1 was blockaded with vehicles, bodies, and equipment. There was no way around it. “That’s when I decided to go to Red Beach 3.”

John ran further along the sand toward Red Beach 3. At this beach a weaponless John observed a set of makeshift stairs that ran along the cliffs. “They must have been built by the Japanese. There were a couple hundred stairs and they ran all the way up.” This pathway seemed the only way to link up with his unit. He began to crawl up the side of the stairs.

“All the way to the top there were dead Marines along the stairs. They were slumped over and all appeared to be shot through the head and face. They each had just a small trickle of blood running from between their eyes.”

The bodies of Marines who had attempted to ascend the stairs were scattered over the hillside. They were the victims of earlier waves, and John gazed at each one as he climbed around them, the lifeless bodies serving as markers the higher he climbed.

“Every one of those guys I saw dead …. ” John had to pause. The memory of the fallen Marines still haunted him. “Every one of those guys, my heart went out to them.” Nearly 80 years later, the tears still came.

What happened when you got to the top of the stairs?” I asked.

“Then I found my outfit!” John said, a smile on his face. Reuniting with his field artillery battalion was obviously a much happier memory. “Right then and there I found my guys.”

Fox Battery was set up not far from the summit of the cliff John had climbed. Their guns had been dragged into position in the earlier two waves.

“The first man I saw was a forward observer from my battery, a lieutenant. I didn’t want him to know I didn’t have a rifle, so at this point I’m still trying to look for a weapon. I didn’t look long before we had our first fire mission.”

John’s attempt to arm himself would have to wait. The 75 mm howitzers were ready to fire.

“I lost count how many shells we fired. The forward observer was giving us coordinates all day, and at night we shot illumination rounds. By day two we were running out of ammunition.”

John’s battery was doing a historic job grunts of the 5th Marine Division.

At night, however, things got weird. An unknown voice called out to them. “Fox Battery, where are you? Fox Battery, where are you?” The voice seemed to come from far in the distance. “We found that so strange. We were taught never to call out to one another in the night. So we hid low behind our guns and ignored it.”

John believes it was Japanese soldiers testing to see if they could infiltrate. Some Marines and forward observers had gone missing. There was no way to tell if they had been tortured or killed for information by the Japanese.

“The next day, day three, we totally ran out of ammunition for our howitzers,” John said. The Marines of Fox Battery made multiple runs to and from the beach trying to track down any ammo they might find for their guns.

The less they fired, the less protection the infantry had. As an artillery man, you were the king of battle and often the hand of God. It was artillery that could knock down rows of banzai charges.

Ammunition finally reached the beachhead, and men ushered rounds to Fox Battery’s position. The new high-explosive shells had arrived just in time. Enemy counterbattery fire was incoming.

“Luckily we had a time-fire radar. We could adjust quickly and knock them out.”

By day seven, Fox Battery’s position was known to the enemy. The Japanese zeroed in. Enemy counterbattery poured in faster than John and his gun crew could adjust. Finally their ability to return fire ceased altogether when an enemy shell exploded to their left. The Japanese artillery blew John and the other Marines off their howitzer like rag dolls.

Stunned and temporarily deaf in both ears, John lay facedown in the dirt. Other Marines were scattered around. They slowly attempted to get up and get back to the gun. John found he could not bounce back like the others. As they sat him up, he looked down below his belt line. There was smoke coming from his groin. He had a large hole in his pants. He was hit.

“I placed my hand in my pants. I was hit right by my family jewels,” he said quietly.

John was bleeding heavily. As the men shouted for a corpsman, the roar of other artillery pieces firing drowned their screams for help. John tried to staunch the blood loss from his groin, but soon passed out.

“When I gained consciousness, I was in a tent hospital. I looked down at my groin. I could see they did a good job fixing me up, and I passed back out.”

It was a relief for a 19-year-old boy to know he still had his penis and testicles. Still under a considerable amount of morphine, John was transported to a hospital ship offshore for more rehabilitation. While John was out of the fight, the battle for Iwo Jima raged on.

“Dealing with my injuries was some delicate stuff. You could put three or four fingers into my wound,” John explained. He would spend the next five months recovering in hospitals both in Guam and Hawaii.

John was ultimately satisfied with the healing process. He could have lost his manhood on Iwo Jima. Thanks to surgeons, he was able to have a normal life and create a family.

“I came home and later joined the sheriff’s department on May 1, 1950. I retired in 1978.” John retired as the deputy warden of the Essex County Jail in New Jersey. In the prison system he would run into other Marines who had chosen to go down a different road after the Battle of Iwo Jima. “It makes you think if the war contributed to the behavior of some Marines after their return home from combat.”

John had a point. Like many others, he and I both had chosen law enforcement after the Marines. By doing so we were at times confronted with the fact that some Marines chose crime.

As I placed the rifle into its case, I believed my time with John had come to an end. “Where do you think you’re going?” he asked.

“Well, I got a long drive back to Boston.”

“You aren’t going anywhere until you have some of my meatballs!”

John hobbled over to the kitchen and turned on the burners on the stove to warm up a pot. A few minutes later, he was off-loading giant meatballs on a plate for me.

I knew I had a long drive from New Jersey to Boston ahead of me, but I sat down with the Italian-American Marine. I bit into one of the meatballs he had made, and he told me I couldn’t leave until I was finished with my meal.

I can honestly say they were the best damn meatballs I ever had.

Author’s bio: Andrew Biggio is a Marine veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is currently serving as a Massachusetts police officer and is the president of the nonprofit Boston’s Wounded Vet Run. “The Rifle II” is his second book.