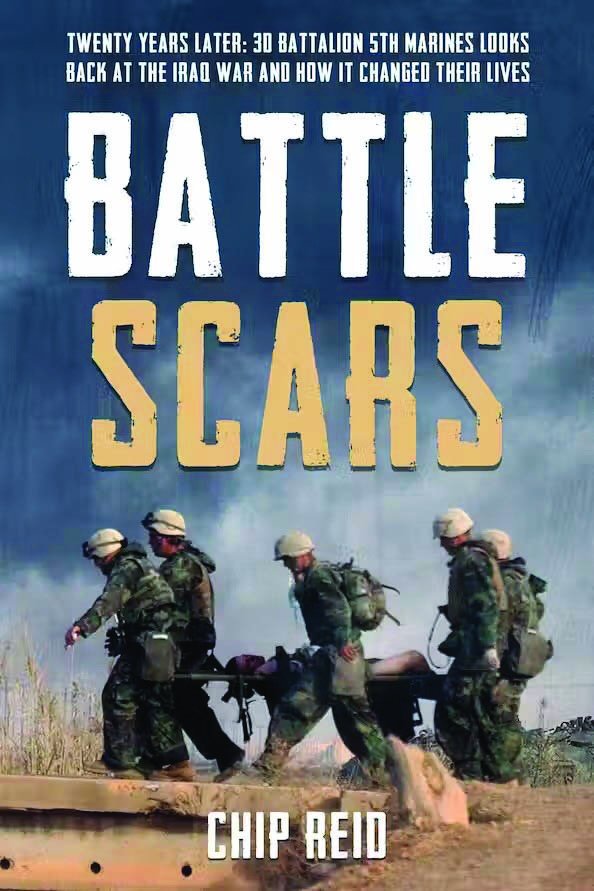

Battle Scars

By: Chip ReidPosted on May 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: In 2003, NBC News journalist Chip Reid embedded with 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines during the opening days of OIF. He spent six weeks living with the Marines and telling their stories to TV audiences back home. He developed a better understanding of what it means to be a Marine—he also developed a profound respect for these young men and the sacrifices they made. Twenty years later, Reid interviewed those Marines again. In this book he tells their inspiring stories of heroism in battle, camaraderie, patriotism and belief in the mission. Reid also writes about recovery from wounds—both physical and mental—and delves into the new appreciation for life that results from post-traumatic growth. We chose to publish this excerpt in this issue because June is PTSD Awareness month, and hope that it reinforces the importance of speaking openly about mental health issues. For information about resources available to veterans, visit: www.mca-marines.org/blog/resource/resources-for-veteran-marines/

Preface

On Thanksgiving Day 2021, while driving from my home in Washington, D.C., to the Philadelphia suburbs for a family dinner, a souped-up pickup truck roared past me on I-95. It had temporary plates and two Marine Corps stickers, one on the rear window and one on the bumper. I thought: “Isn’t that just like a Marine. He just bought the damn thing and it’s already plastered with Marine Corps stickers.”

That got me thinking about the most challenging, gratifying, jaw-dropping, and frightening story I covered in my 33 years as a journalist—the slightly less than six weeks I spent embedded with 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, as a correspondent for NBC News.

For years I had thought that one day I would escape the journalism rat-race and write a book, but I hadn’t settled on a topic. “That’s it!” I thought as the pickup disappeared out of sight. For the 20th anniversary of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2023, I would write a book about the Marines of 3/5.

As I drove, I thought of questions I wanted to ask them. Where are they today and what are they doing? Do they have families? How did their lives change due to their first combat experience? (It was the first combat for almost all of them.) What did they learn as Marines that helped them prosper in civilian life? Did they struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? What do they think about the war today?

When I returned home, I reached out to some of the Marines I had occasionally stayed in touch with and started asking questions. I found their stories fascinating and powerful—and they were eager to tell them. They clearly did not want their service and their sacrifice to be forgotten.

At first, I thought I could get a good cross-section with about a dozen Marines, but word spread about my project and requests to be included started pouring in. Eventually I interviewed more than 40 Marines, plus several wives and grown children, whose experiences and insights were often as engrossing as those of the Marines.

I was often surprised, sometimes stunned, by their honesty, how deep they reached to tell me their stories. On several occasions I heard the words “I’ve never told this to anybody who’s not a Marine, but …”

I was deeply gratified that they still trusted me after all those years. Many of them talked about arriving home from Iraq and discovering that their families knew all about where they had been and what they had done because they had been glued to NBC and MSNBC, waiting for my frequent updates on their progress along the road to Baghdad.

Whenever I appeared on TV, I was later told, the phone tree would “light up” with wives, mothers, and other loved ones speaking only two words before hanging up: “Chip’s on!”

Of course, their passionate interest in my reports had nothing to do with me—it was because they were desperate for information about their Marines. Where were they? What were they doing? Were they in danger? Had anyone been injured—or, heaven forbid, worse? When were they coming home? They hoped to catch a glimpse of their Marine in the background of my live reports—or even better—to see and hear him in an interview. I interviewed as many Marines as I could convince NBC and MSNBC to put on the air.

One of my most prized possessions is an immense photo book with “Marines” stamped on the front in gold letters. It contains dozens of letters and family photos from the Marines’ wives, girlfriends, fiancées, parents, grandparents, etc., thanking me and my crew for enduring battlefield conditions to report on their men.

This book is a tribute to the dozens of Marines I interviewed, and to everyone who served in the Iraq war. Many of the Marines I interviewed also served in Afghanistan, so I think of this book as a tribute to all who served in those wars.

World War II and the Iraq War, of course, have very different places in American history. World War II saved the world from fascism and dictatorship. The Iraq War, by contrast, is a war that many Americans, especially young ones, know little about. Many Americans who do know about the war believe it never should have happened.

I had serious reservations about the war in Iraq even before it began. But I believed then, and I believe even more strongly now, that the stories of those who fight our wars should be told. Even if a war is unpopular, even if you think it was a mistake, our men and women in uniform put their lives on the line and answered their nation’s call.

In writing a tribute to the Marines of 3/5, I believe it’s important to honor not only their service, but also their sacrifice—in battle and in the two decades since. Indeed, there is quite a bit of sacrifice in the pages that follow, including death in battle; death by tragic accident; life-changing injuries; and the whole panoply of nightmarish symptoms of PTSD. Also, of course, addiction, divorce, and suicide, which tend to plague the armed forces to a greater degree than the non-military public.

But there is also much that’s positive and life-affirming in this book: heroism in battle; the intense, life-long camaraderie among Marines; patriotism and belief in one’s mission; life-changing traits learned as Marines; and the post-traumatic growth that often follows PTSD.

For the most part, I have told the 2003 Iraq invasion story chronologically, from Kuwait to Baghdad, while interspersing that account with stories from the past 20 years about Marines who were affected by specific battles and other incidents along the way. It took only 22 days for the Marines of 3/5 to fight their way to Baghdad, but the effects on those who fought in that war have lasted two decades.

As the convoy moved toward Baghdad and the Marines came under attack almost daily, I was awed by the fact that men as young as 18 and 19 were charging forward under machine-gun fire and making instantaneous life and death decisions at an age when my biggest worries were who to take to the high school prom and what courses to take in college. I developed enormous respect for their courage and devotion to duty. That respect only increased during my time writing this book.

From someone who doesn’t have a military bone in his body, this is my small contribution to ensuring that the service and sacrifice of our men and women in uniform—even in unpopular wars—are not forgotten.

Marine Families Tell Their Stories:

The Martinez Family

In early September 2003, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines came home from Iraq after a seven-month deployment. NBC News asked me to cover the homecoming of “my” battalion. I met Joe Klimovitz, who was my cameraman in Iraq, at Camp Pendleton in Southern California.

We waited for the Marines to arrive, standing with their wives, newborn babies, mothers, fathers, and other family members, who profusely thanked us for our reports. In previous wars, those with loved ones on the front lines often went weeks or months without hearing a word. With our live and taped reports airing multiple times every day, the families kept their televisions tuned 24/7 to MSNBC or NBC.

The Marines arrived in three waves with the last arriving at 2:30 a.m. The families of the final group had waited in a state of nervous excitement for more than eight hours. When the Marines finally got off the buses, Klimo shot video of the emotional reunions and I did interviews for stories that would air later that day.

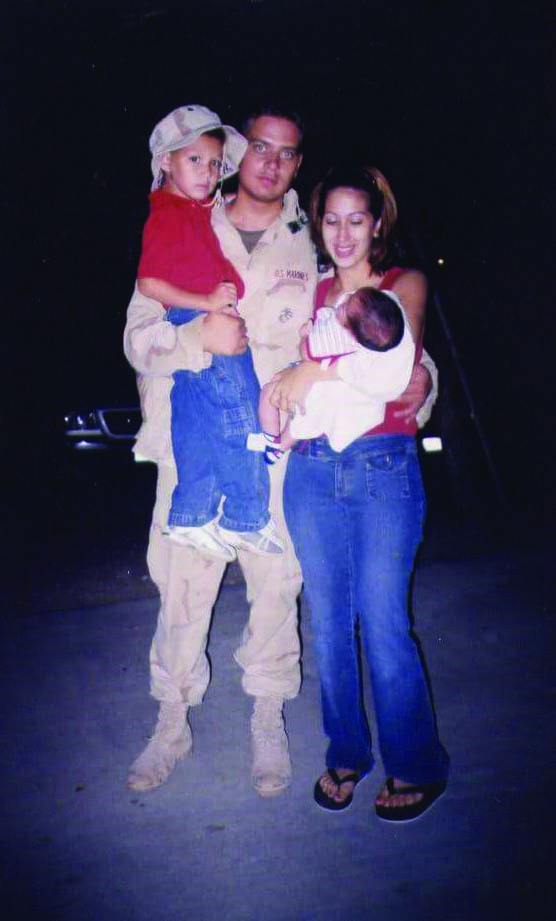

Looking at those stories years later, one of the lines I wrote stands out: “Many here say that after so long apart, getting back to normal will be hard work.” That turned out to be an enormous understatement for many of the Marines and their families, including Corporal Mike Martinez, who held his son Mike Jr., while I interviewed him and his wife Stefanie, who held their newborn son Scott.

A photo of this moment is included in this book. Stefanie was overwhelmed with joy to have their family reunited, but Mike was stoic and distant. Looking at his eyes, he appears to have what is known as “the one-thousand-yard stare.”

At the time, I thought that’s just the way Marines are. They don’t like to show their emotions. And of course, he must have been physically and mentally exhausted. In fact, though, as I later learned, the extreme disconnectedness of some of the Marines, including Martinez, was also a sign of difficult times to come.

Almost 20 years later, I interviewed Mike and Stefanie Martinez again, this time on Zoom from their home in California. Their son Mike Jr. is in the Air Force and joined us on Zoom from a base in Italy. Son Scott, a Midshipman at the United States Naval Academy, joined us from Annapolis, Md.

My first impression of the family on the screen in front of me was of the quintessentially happy military family—the proud father wearing a shirt with the Marine Corps eagle, globe, and anchor symbol, sitting next to his beautiful, smiling wife; the sons, Mike Jr. and Scott, both handsome young men proudly following in their father’s military footsteps. And in fact, I was right. They are a happy family. But it took a long time, a tremendous amount of patience, and a lot of love to get to this point.

Mike had told me before the interview that he struggled mightily with PTSD for several years following his 2003 deployment in Iraq, so I approached the topic gingerly because his family was present. He told me not to worry about it. He was totally open to any question I wanted to ask. “They know 100 percent,” he said.

All four members of this courageous family were not just willing, but eager, to talk about their struggle in detail. Their hope is that other families can learn from their difficult experience. Perhaps someone else who reads this—and is driving his family to the ragged edge because of PTSD—will seek help right away, instead of putting it off for 15 agonizing years.

Mike said he had several symptoms of PTSD, including explosive anger. Just about anything could set him off. He had such a short fuse that his family was always “walking on eggshells.”

Mike Jr. said there was never any physical abuse—but the mental abuse was at times, severe. His father could explode without warning. He said it was like living with a drill instructor. “We were scared. I was always angry, hearing my dad going off on our mom. Why is he doing this? Why is he like this? I didn’t understand at the time.”

Younger brother Scott said: “It was something that we just had to keep going through and endure, despite the fact that we knew it was wrong.”

There were some good times. Even some good years. “It wasn’t 24/7,” wife Stefanie said. “It would come and go in spurts.” But the bad times always seemed to return.

Anger was not Mike’s only PTSD symptom. Many veterans with PTSD suffer from addiction. Mike’s addiction wasn’t drugs or alcohol. He medicated himself with food, gaining an enormous amount of weight and peaking at 340 pounds. That made him even more frightening. Stefanie said his attitude was: “I’m big and intimidating, and I don’t care what people think.” Mike said his mindset, before he sought help, was: “This is just who I am. I’m the big bad guy. I’m right, you’re wrong.”

Much of that attitude was aimed at Stefanie, who says the hardest part was that she always doubted herself. “I always felt like there was something I did wrong. Everything I did was never right, and I couldn’t keep him happy.” She was often too frightened and confused to respond to his outbursts. “I would always shut down. I couldn’t say anything.”

Her job, she said, was to try to keep peace in the household. When Mike was angry, she would sneak away to warn the boys. “Just stay away from dad, he’s in a mood,” she would tell them. “I was always protecting them so they wouldn’t get the brunt of the anger,” she told me, as her husband nodded in agreement beside her. Mike’s PTSD almost tore the family apart. “There were moments where I wanted to just give up and leave, take the kids and go,” Stefanie said. “There were many nights I cried myself to sleep because I just didn’t know what else to do. I was stuck.”

She said three things kept her going: her sons, her faith, and her commitment to helping her husband climb out of the dark hole he was in. “Don’t give up. He needs you,” she would tell herself. “You have to stay. You love him. And I do. I love him to death. And I decided, I’m going to fight for him. I have to fight for him because he’s not fighting for himself.”

Mike had sought help at the VA in 2007, but says they weren’t helpful at all. A nurse even told him he needed to “suck it up.” Instead, he gave up. It took him another 12 years to try again. For most people, New Year’s resolutions rarely meet with success, but on Jan. 1, 2019, Mike’s resolution was to get help. And it turned his life around.

He started seeing a therapist who guided him through his time in combat and the horrors he had witnessed, zeroing in on one particular incident—the death of Michael “Doc” Johnson, the battalion’s first fatality in 2003. For years Mike had blamed himself for Johnson’s death, even though his reasoning made little sense. This is how he explained it: “When Johnson got hit, I felt like I failed. As a forward observer my job was to call for fire, to provide support for anybody who’s in need. I broke my radio; I could not maintain communication. My one job was to maintain communications. I could not do that. Because I failed, Johnson died.”

With the help of his therapist, and the strong support of his family, he finally accepted the fact that blaming himself was absurd. “It’s the Marine Corps,” he says now. “… Things break. It was absolutely not my fault that Doc Johnson died.” That was the beginning of the end of 15 years of self-imposed torture over unfounded feelings of guilt.

Eventually he reached the light at the end of the tunnel—and turned PTSD into Post-Traumatic Growth. Stefanie, who attended some of Mike’s therapy sessions, says his turnaround has been the answer to her prayers. He’s growing in ways that amaze and inspire her. He’s going to school, with the goal of trading his monotonous job at the post office for his dream job—teacher and sports coach.

“He’s now in a very happy place,” she says. “He’s very content with his life now.” Mike calls it a “positive place,” a dramatic change from the constant negativity of just a few years ago. And he adds that there’s no chance he could have made the change without the love and support of his family. “They were my rock,” he says. He now has a new mantra: “Better every day.” A vast improvement, he says, over his previous mantra: “F— ’em.”

Scott sees a silver lining on the dark cloud of his father’s PTSD. It taught him an important life lesson. “We saw firsthand what PTSD can do to those around you,” he said. “I feel like we have a different understanding than what the average person has.”

Epilogue

And here’s an update on Mike Martinez. During his interview he said he wanted to leave his tedious job at the post office and pursue his dream—to become a teacher and a coach. Well, guess what. He did it. In October 2023, while I was narrating this audiobook, I received the following email from Mike: “After reading the transcript from our interview, I wanted to update you with more information. I have now finished my bachelor’s degree program and I am working full time as a 7th grade math teacher. I also became the head coach for our high school cross country and track and field teams. I genuinely believe PTG is real but strangely must appreciate the PTSD that allowed me to rebuild myself into something that I never thought was possible. I guess it’s true that you can’t have a rainbow without the rain.”

Author’s bio: Chip Reid’s journalism career has spanned 33 years. In addition to being embedded with Marines during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Reid reported from Ground Zero and the Pentagon after 9/11. He has also covered stories on the war on terror from Afghanistan, Israel, Gaza, Uzbekistan, Egypt and around the world.