A Shared Hardball History: Pre-World War II Marines, Japanese Were Friendly Foes on the Diamond

By: Kater MillerPosted on March 15, 2024

In August of 2021, the Japanese national baseball team won the gold medal in the Olympic Games. They defeated the United States 2-0 at Yokohama Stadium, in the same city where Japanese and American baseball teams squared off against each other for the first time more than a century ago. The two countries have a long, shared history of baseball. Because Marines have been stationed across the globe, they found themselves in a position to take part in these international baseball games, which many people hoped would foster goodwill and promote peace between the two rising superpowers of the early 20th century.

The United States’ global influence expanded rapidly on the heels of the Civil War. One of the main exports that followed was baseball, which exploded in popularity domestically during the war. Americans took the game to far-ranging outposts, playing it among themselves to relieve boredom, and planting its seeds in the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, the Philippines and Japan—all places where baseball is still very popular today. Major General John A. LeJeune bragged, “Everywhere we go, we leave them basball.” This notion is somewhat true, but the truth is a little more complicated. For instance, Cuba had already had a professional baseball league for two decades by the time the Marines showed up during the Spanish-American War in 1898. In fact, Spain had tried to suppress baseball because it was rivaling bullfighting as the most popular sport on the island. It was American and Canadian missionaries who spread the game well before the U.S. Marines showed up to play.

American businessmen also took the game of baseball with them as a recreational pursuit, but for the most part, they had no interest in expanding the game outside of their enclaves. The missionaries wanted to include a form of physical education in their foreign schools and often introduced the sport to local students as a form of exercise. Many believed that they were teaching American-style values to their students, and that would help them to become “civilized.” In China and Japan, baseball would become very popular by the end of the 19th century.

In treaty ports such as Yokohama, foreign athletic clubs catered to European and American members. Rugby, cricket, and baseball were popular pastimes among the inhabitants of the foreign settlements. The Yokohama Athletic Club, founded in 1868, was initially almost exclusively British. Over time, Americans supplanted the British, and baseball supplanted cricket as the most popular sport played at the club by the late 1880s. According to Donald Roden, author of the article “Baseball and the Quest for National Dignity in Meiji, Japan, published in The American Historical Review, Americans living in Japan used baseball as a way to express their national identity.

Sports clubs in treaty cities restricted access to Japanese athletes. They could not participate in the sporting events, but they were hired to maintain the grounds on which the games were played. Despite the prohibition, a Japanese baseball team from Ichiko University challenged the American baseball team in Yokohama in 1891, but the Americans declined. Undeterred, the Ichiko side continued to challenge the Americans. Because of the restrictions, the Americans declined for nearly five years before finally relenting. They agreed to play, and the May 23, 1896, game was a lopsided and embarrassing defeat for the Americans. The students of Ichiko trounced the Americans 29-4. On June 5, the Americans agreed to another game, hoping to avenge the loss. The team bolstered their roster by using extra players from the U.S. Navy vessels in Yokohama Harbor. These efforts did not achieve their desired results, and the Americans suffered a similar humiliation, suffering a 32-9 defeat. A third game eventually went the Americans’ way after they pulled more ringers off of the newly arrived USS Olympia, according to Roden.

At this point, baseball’s popularity exploded in Japan. Roden recognized that Americans in Yokohama played baseball to maintain their identity as Americans, viewing it as a rugged, individualist sport, while the Japanese players found that baseball aligned with their collectivist ideals. They felt the team sport was better suited to underpin collectivism than individual sports like judo. Baseball took on whatever ideal the players needed it to take. Americans saw their turn at the plate as an expression of their independent nature, as man-to-man combat. Japanese players saw their turn at the plate as an opportunity to sacrifice themselves for the good of the team.

Japan, like America, started an age of expansion towards the end of the 19th century. When the Japanese Navy crushed the Russian Navy in the 1905 Battle of Tsushima, the western powers took notice. The Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese war changed the military dynamic in Asia, and the United States began to view Japan as a potential adversary. Both nations wanted to keep a foothold in the Pacific Ocean, securing islands to use as bases to re-coal their fleets. War with Japan seemed like a very real possibility after Japan’s annihilation of the Russian fleet.

Because baseball had become so popular in Japan, both the United States and Japan thought that college and all-star tours of each other’s countries would foster a sense of goodwill and enhance the chance for peace. Baseball seemed like a good way for the countries’ young men to meet, compete peaceably and foster good diplomatic relationships. These tours started in 1905, when Waseda University’s baseball team toured the United States and lasted through the 1930s. The most notable of these was the 1934 American all-star tour of Japan, which featured superstars like Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth.

Marines also played baseball against Japanese teams nearly until the United States entered World War II. In 1910, Waseda University played a series of 24 games in Hawaii against local civilian teams, U.S. Army teams, a U.S. Navy team and the Marines. Waseda won 11 of their games, including two games out of three against the Marines. This would be the first of many games between Waseda and the Marines over the next 23 years, the most high profile of which was a 1927 game in Quantico, Va., with Japanese Ambassador Tsuneo Matsudaira and Commandant John A. Lejeune in attendance.

Waseda University was a frequent opponent of the Marines in China as well. It was in China that the Marines and Japanese teams faced off against each other the most often. Both countries enjoyed equal footing in the international settlements in the Chinese concessions, and both countries used baseball as an opportunity to exhibit national pride.

There were two areas of China where Marines regularly played sports. The first was in North China and included the cities of Peking and Tientsin. The Marines of the Legation Guard joined the North China League, a baseball league composed of the American and Japanese businessmen of the foreign settlements in those cities, and the 15th Infantry, a U.S. Army unit in Tientsin. Occasionally, the teams of visiting U.S. Navy ships joined in. The earliest games were in the 1910s, and they continued until the onset of WW II.

The second area was Shanghai. In 1927, a civil war in China was about to erupt. The Marines sent the 3rd Brigade, under the command of then-Brigadier General Smedley Butler, to Tientsin and Shanghai to protect the international settlements there. Much of the brigade went to Tientsin, and they formed a baseball team that joined the North China League.

The 4th Marines went to Shanghai and stayed there until 1941. They found that the city was rife with sporting competitions, including polo, soccer, rugby, tennis, bowling and baseball leagues. The American and British civilian population living in the international settlement made dozens of sports fields. The city boasted five YMCAs, one of which catered exclusively to the U.S. military personnel. There were several baseball fields in Shanghai but the most well-kept was at the Shanghai Race Course. The race course itself tended to be a major hub of sports and military activity. Since the 4th Marines’ billeting was dispersed through the city, the track’s infield was a place they could drill and pass in review. The facilities included a grandstand, a baseball diamond, tennis courts, cricket pitches, several soccer and rugby pitches, and tees and greens to play golf shoehorned in between everything else. Chinese laborers meticulously maintained the race course; its baseball diamond was one of the best in the world.

Shanghai’s thriving sports atmosphere benefited the Marines’ physical conditioning, but some commanders did not see it that way. One Marine officer lamented the fact that duty in the city was making his troops soft—the infrastructure did not allow the Marines to practice field problems, and they had to perform forced marches through the city streets early in the morning before commuters choked them off. Marines drilled and paraded through the well-maintained infield of the Shanghai Race Course and the Columbia Country Club, some of the only training spaces available to them. The commander wanted his units to rotate through the Philippines, where they could do proper military activities in a harsh environment to toughen up.

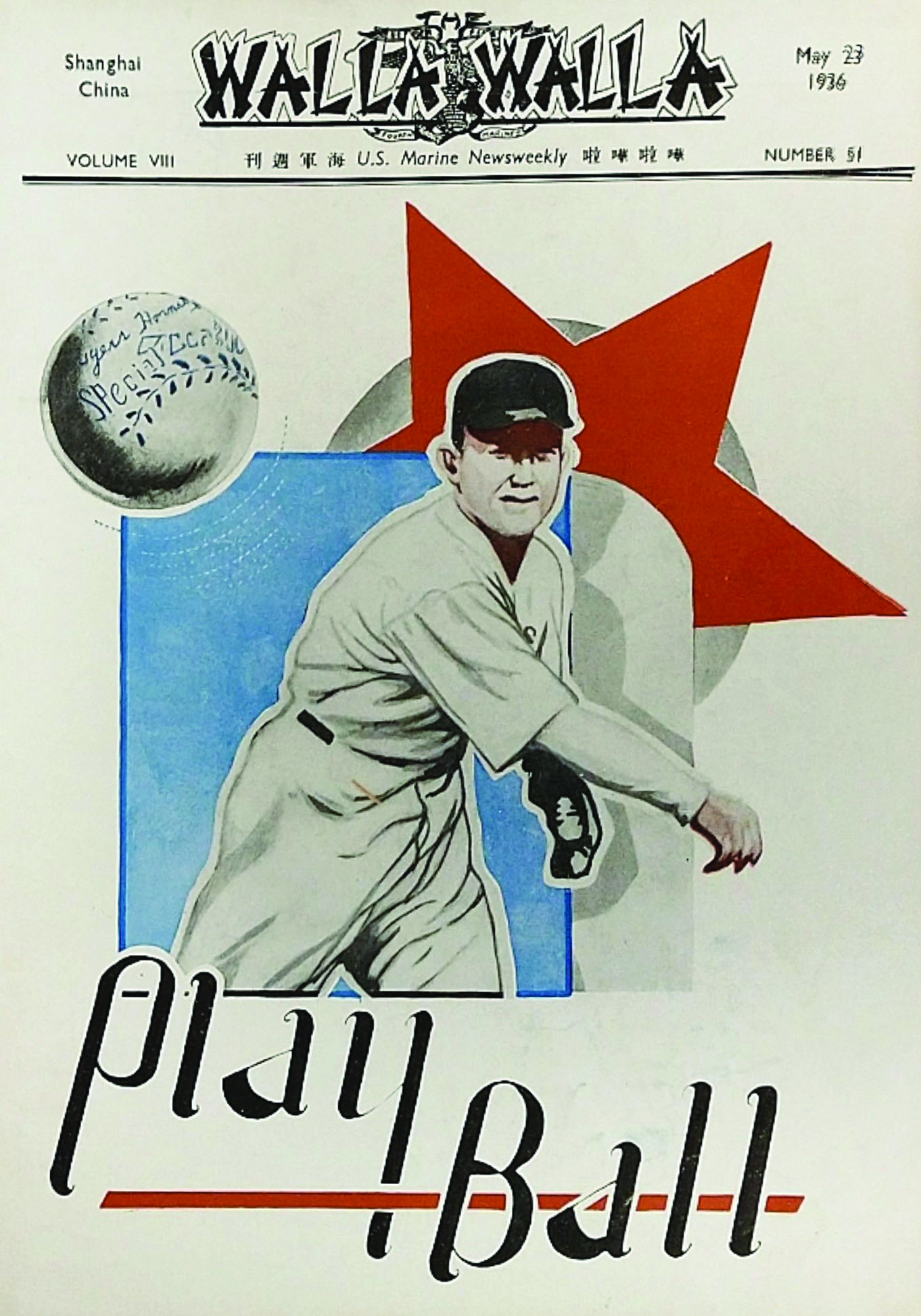

Due to the lack of regular military training, the 4th Marines in Shanghai were a perennial baseball powerhouse playing through the Shanghai baseball matrix. The teams in the league generally consisted of civilian businessmen and government officials called the Amateurs and U.S. Sailors anchored on the Man of War Row on the Huangpu River or the Yangtze River Patrol. Some years, the 4th Marines fielded a regiment-wide team. Other years, each battalion and the headquarters fielded their own teams. And some years included Japanese and Chinese civilians. The league was quite multinational.

The Peking Marines unsuccessfully attempted a goodwill tour of Japan in 1925. In 1930, the 4th Marines managed to tour the country, where they were welcomed by throngs of cheering fans. They played 14 games against college and corporate teams and won 10 of them. Leatherneck published an account of the tour in January 1931. The 4th Marines failed in an attempt to tour the country again the following year.

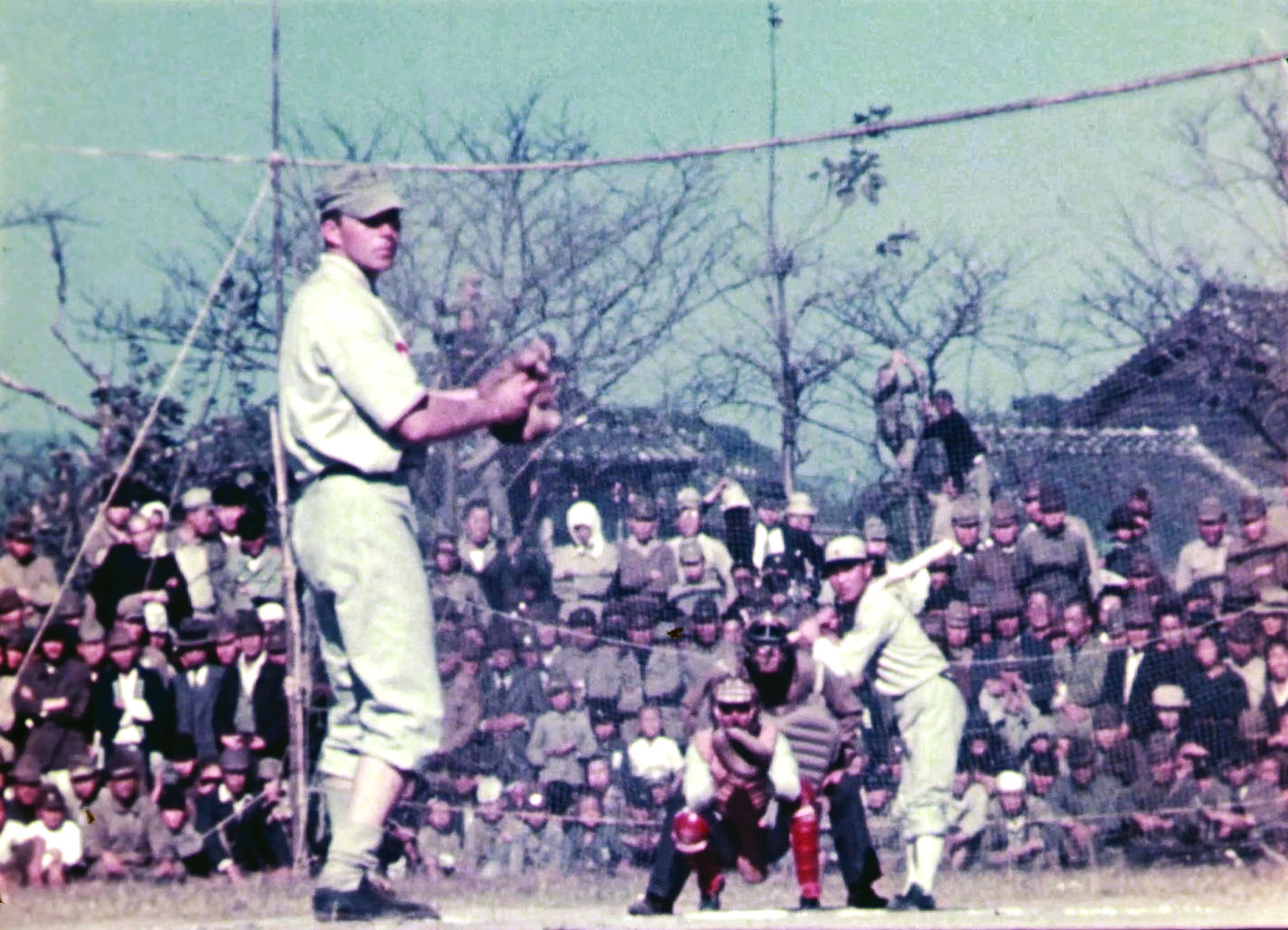

In the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese colleges and high schools toured China, playing games against Japanese and American baseball teams. Year after year, the Marines played against touring Japanese universities like Waseda, Keio, Meiji, Tokyo, the Saga Commercial School, and others. The visiting Japanese students usually gave the Marine teams a tough time. They used Japanese baseballs (slightly smaller than American ones), hired local Japanese umpires, and let the Japanese team set the ground rules. They usually played at the Hongkew Park diamond, which was in the Japanese defense sector of Shanghai. The games had an air of mutual respect and cordiality. Marines in China talked every year of how exciting the visiting colleges were because of their remarkable style of play.

In July 1936, the Golden Dolphins, one of Japan’s first professional baseball teams, traveled to Shanghai to play baseball. They planned to play the 4th Marines, American civilians and the Japanese civilian baseball teams in a best two-out-of-three style tournament. They handily defeated each team in succession and won without the need to play the third game. The Americans made an all-star team of Marines and civilians, which the Golden Dolphins beat as well. The North China Herald reported that the professional side was going to travel to Tientsin to play another game against the Marines there, but no record of that game was reported in the English newspapers of China.

The Meiji University team visited in the summer of 1937 and beat the Marines twice, the American civilians twice, and the local Japanese civilians once. They then beat an all-star team of Marines and civilians 10-0. The visiting team sent a letter of appreciation to the Marines for the spirit of their play, which they published in the July 31, 1937, edition of Walla Walla. The visit from Meiji was one of the last times Japanese universities sent teams on tours to China, because the Second Sino-Japanese War began to erupt through the country.

Not for the first time that decade, Marines watched firsthand as China and Japan edged closer to war. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, and hostility between the two nations boiled over. In late January 1932 the Japanese military stationed in Shanghai attacked Chinese army units in the district of Chapei. Marines took defensive positions along the Soochow Creek, which separated their defense sector from Chapei. They watched as Japan burned the district in the two-month-long battle. A Japanese bomber, operating from an aircraft carrier off the Chinese coast, bombed a cotton mill, injuring a few Marines who were billeted there.

The Japanese attack on Chapei ended in March. Though many of the Marines felt he baseball season, and that summer at least two Japanese college teams visited. Those were the Saga Higher Community College and Ritsumeikan College. The 1932 Shanghai league included a team of Japanese businessmen and a U.S. Army team from the 31st Infantry Regiment, which deployed to the city during the crisis to reinforce the Marines.

But in late summer of 1937, Japan took a more aggressive posture in China. Fighting once again erupted in Shanghai, and the Japanese fought to drive the Chinese military away from the city. In October, the North China Star reported that a Golden Dolphin pitcher who the previous year had embarrassed the teams of Shanghai, identified only as “Matsumoto,” joined the Japanese Army and was sent back to China, where he was killed in action.

Relations between the Japanese and American governments rapidly unraveled. The Marines were ordered to keep the armed non-American units out of their sector by any means necessary. After several months of intense fighting, the Japanese succeeded in expelling the Chinese fighting forces from Shanghai and acted more belligerently toward the other countries of the international settlement. They attempted to bring armed troops into the American defense sector, where Marines resisted their ploys to conduct armed patrols there. In December 1937, the Japanese bombed the USS Panay (PR-5), of the Yangtze River Patrol. The bombing killed three U.S. Sailors and wounded dozens more. President Franklin D. Roosevelt considered a military reprisal against Japan, but the isolationist stance of the United States pervaded. Eventually, the Japanese government apologized and paid for the damage done to the ship.

After the fighting of the previous year, the 1938 Shanghai baseball league consisted of three Marine teams and one team of American amateurs. Gone was the cooperative atmosphere from earlier years. The Second Sino-Japanese war raged through the country, and it looked like war was imminent in Europe. The foreign military contingents evacuated Shanghai, leaving the Marines in an increasingly vulnerable position. The baseball league in Shanghai survived through the 1941 season, but only American teams entered the competition in the final three years.

International baseball lasted a little longer in Peking and Tientsin. Between 1929 and 1938, the only Marine Corps team in North China was the one put together by the Legation Guard. In 1938, the 15th Infantry left Tienstin, and the Marines took over their compound. They fielded a second team, used the 15th Infantry’s Can Do Field and joined the North China League.

In 1939, Marines faced off against a baseball team from the Japanese Embassy, winning 6-4. In the summer of 1940, the Marines played one final baseball game against a Japanese military team. They used a rubber baseball, as the leather-covered baseballs were becoming hard for the Japanese government to supply. The Japanese team beat the Marines 14-1, but in consolation, the Marines were treated to libations at the Japanese club after the game. The camaraderie of the baseball teams in 1940s China was one of the last times the two countries would be on good terms until well after WW II. At least three of the Marines who played in the final July game later ended up as prisoners of war.

During WW II, the sport endured domestically—America always has baseball. Japan was forced to withdraw from the sport until their eventual surrender. Baseball returned to the Japanese populace after the war as a way to regain normalcy. It seems fitting that the two nations are still facing off—and that Japan won its gold-medal game in Yokohama, where the games between the two countries began.

Author’s bio: Kater Miller is a curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps and has been working at the museum for 12 years. He served in the Marine Corps from 2001-2005 as an aviation ordnanceman.