The importance of the strategic concept

Effective military education and training do not take place in a vacuum. Rather, both are elements in a force planning strategy that implements the Service’s strategic concept.1 It is the Marine Corps strategic concept that defines and drives its education and training requirements, and those requirements should determine the architecture of its schools and curriculums.

For its first one hundred years, the Marine Corps’ strategic concept required no formal education or training. Marines “were aboard ship to protect the ship’s officers and the vessel from the crew, many of which were or might be drunkards, malcontents, thieves, arsonists, thugs and mutineers,” and “were basically soldiers detailed for sea service whose primary duties were to fight aboard but not sail their ships.”2 This Service’s force plan centered upon ships’ detachments, which sometimes were used ashore to strengthen naval landing parties.

This changed after the Mexican War (1848) with the Marines’ primary missions altered to that of going ashore to protect American lives and property, manning ship’s guns, and quelling civil disorder. These were still missions that could be accomplished by provisional battalions and regiments organized from Marines drawn from ship detachments and Marine Barracks, but these larger landing forces required some basic training, and new officers and enlistees were joined to Marine Barracks for a prescribed initial period of instruction.

As modern steel battleships were developed, a higher technical proficiency was required of crews, requiring more extensive naval training. This led to greater Navy professionalism and less need for a ship’s guard. Generally, Navy officers began to view Marine officers as their intellectual and social inferiors, and beginning in the 1890s, an influential cadre of Navy officers tried to eliminate Marines from ships altogether.3 The reform-minded Colonel Commandant Charles McCawley, who had seen his own position as Commandant reduced in grade to colonel from brigadier general, addressed the difficulties through a major reorganization of the Corps. As part of this reorganization, all of the 50 officers joining the Corps between 1881 and 1897 were Naval Academy graduates, promotion examinations were instituted for corporals and sergeants and included “reading, writing, and the simple rules of arithmetic,” and in 1885, the Navy Department published a Marines Manual: Prepared for the use of The Enlisted Men of the United States Marine Corps, ordering its distribution to all Marines having more than one year left on their enlistments.4 At Colonel Commandant McCawley’s insistence, the distribution of this manual “for enlisted men” was also distributed to all Marine officers.

McCawley’s restructuring continued under Colonel Commandant Charles Heywood. On 1 May 1891, Colonel Commandant Heywood created the School of Application. Heywood located the school at Marine Barracks, Washington, DC, and put it under the direction of Capt D.P. Mannix assisted by SgtMaj Thomas F. Hayes. Colonel Commandant Heywood would also introduce mandatory examinations of officers and fitness reports.5

Unlike the commissioning of only Naval Academy graduates, the creation of the School of Application, the introduction of examinations, and the publication of a Marine Manual were changes in education and training tied to a force planning strategy. Restricting new officers to the ranks of Naval Academy graduates was an early form of joint professional military education (JPME), “grounded in the justification that officers need a common basis of knowledge with each other and with others in the national security community in order to operate effectively,” a justification of JPME that continues.6

Lacking under McCawley and Heywood was a Marine Corps strategic concept. Unwanted, disorganized, flaying, and shrinking, the Commandants struggled to maintain the Corps as a separate Service within the Navy Department. It was the 1900 Navy Board that provided the Marines with a strategic concept.

The 1900 Navy Board, under ADM George Dewey who had claimed that if there had been 5,000 Marines with which to garrison Manila in 1898 there would have been no Philippine Insurrection, formally changed the Marine Corps’ primary mission to defending bases in the Caribbean and off the Chinese mainland—creating what became known as the advance base mission.7 In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt, no fan of the Marine Corps, tried to isolate the Marines from the Army and Navy ships with Executive Order 969 defining the duties of the Marine Corps, in order of priority, as:

- Garrison naval yards and stations inside and outside of the United States.

- Provide mobile defense for naval bases and stations outside the United States.

- Man static naval base defenses outside the United States.

- Garrison the Panama Canal.

- Provide expeditionary duty overseas in times of peace.8

For the first time since the era of sailing ships, Marines had a place within the national security apparatus to develop a strategic concept that would establish the Corps’ education and training requirements for the next forty years.

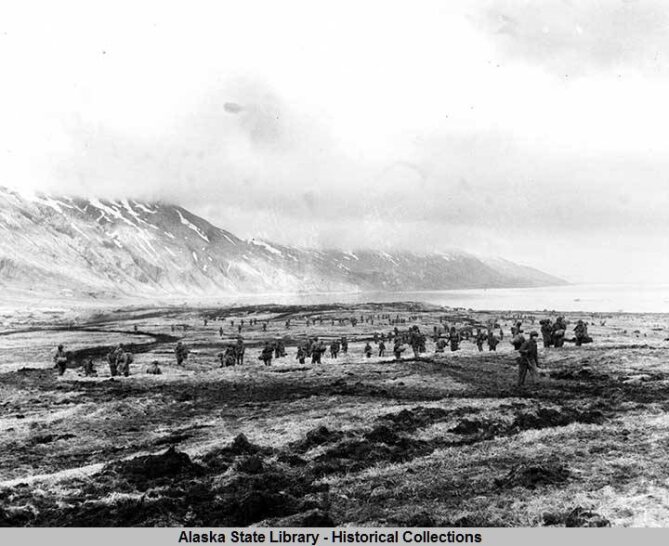

Despite all efforts to reduce Marines to yard guards, the Marines focused on other missions. In 1910, the Corps founded the Advance Base School in New London and created the Advance Base Force in 1913. The following year the First and Second Advance Base Regiments conducted the first advance base exercise on Culebra.

As the Marine Corps focused on advance base operations, its missions of defending bases in the Caribbean and expeditionary duty overseas in times of peace took on new importance. Marines were called upon to fulfill President Theodore Roosevelt’s corollary to the Monroe Doctrine to intervene in the Caribbean and Central America to guarantee European financial interests. Initially, these interventions were peaceful; however, in 1915 the nature of these interventions changed when President Woodrow Wilson offered armed intervention to the Dominican Republic government to protect it from rebels—euphemistically referred to as bandits. “The policy had thus been extended from financial supervision to the necessary control to assure the maintenance of peace.” The issue of whether such armed occupations constituted an initiation of war was resolved when it was agreed, “If you land one section of the Army that is war.” But “you can land a Sailor or a Marine and it is not considered war.”9 In that single sentence, the Marine Corps expeditionary mission was solidified.

While on expeditionary duty in the Dominican Republic and Haiti, Marine Corps education and training would further evolve with the creation of regimental schools in 1922. In addition to valuable bush warfare and counterinsurgency training, these schools also provided Marines with communication and cooperation with aircraft training, marksmanship, using bayonets and grenades, and interior guard. Officers were further instructed in using aviation, artillery, naval gunfire, armored cars, and tactics. Enlisted men lacking general education competencies were enrolled in correspondence courses initially developed by the International Correspondence School (ICS) and delivered through the Marine Corps Institute (MCI).10

A different form of expeditionary duty saw Marines joining the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France where, in addition to providing a Marine brigade for combat, Marines served at all levels of command across the AEF. John Lejeune commanded the Army’s 64th Brigade and three French regiments before taking command of the U.S. Second Division. Eli Cole commanded the Army’s 41st Infantry Division (First Depot Division), and Smedley Butler commanded Camp Pontanezen, a key chokepoint in the AEF’s Service of Supply. Field-grade Marine officers distinguished themselves in command and on the staffs of Army formations. Marine captains and lieutenants did the same leading Army units in combat.11

This experience, coupled with the continued Marine Corps occupation of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, shaped a new Service identity within the Corps. The Marine Corps had developed its own cadre of flag officers and had achieved success in organizing and commanding large formations. The Corps now had Marine Corps bases, independent of a naval yard or station, at Quantico and Parris Island. The Marine Corps began to think of itself as an independent Service within the Department of the Navy. To sustain this independence as a Service would require a significant shift in the strategic concept of the Corps. In January 1920, this shift in Service self-concept saw officer training moved from Parris Island and Philadelphia and formally reconstituted as Marine Corps Schools at Quantico. Also relocated to Quantico were the remnants of the Advance Base Force which had been left at the League Island Naval Yard under the command of temporary MajGen L.W.T. Waller, one of the Marine Corps’ most distinguished and colorful officers, who was too old and too incapacitated for service in France or the Caribbean.

Initially, the curriculum of Marine Corps Schools “mirrored that of the Army’s staff school at Fort Leavenworth and the studies centered around Army doctrine, Army Organization, and Army problems.”12 With the exception of The Basic School, Marine officers were not required to attend Marine Corps Schools, and many elected to attend Army schools instead. Similarly, they could attend the Naval War College or the new Naval Aviation School, bypassing the Company Officers’ and Field Officers’ Course. Within the operating forces, Marines trained in amphibious warfare and advanced base operations with the Navy in Cuba, Hawaii, and Culebra.

Meanwhile, the Marine Corps Schools used the Marines stationed at Quantico to enact large Civil War battles. Under the command of BGen Smedley Butler, the East Coast Expeditionary Force (formerly the Advance Base Force) conducted long field marches to enact large-scale re-enactments of Civil War battles, including Pickett’s Charge while at Gettysburg. In both field exercises and lectures, students at Marine schools were provided instruction on lessons learned in the American Revolution and Civil War.13

For a Service whose self-concept was as an independent Service within the Department of the Navy, its education and training were lacking in both content and focus. This would change with the creation of a Division of Operations and Training within Headquarters Marine Corps, the individual scholarship of Marines such as Dion Williams, the publication of the Tentative Landing Operations Manual in 1934, and command of the Marine Corps Schools passing to James Carson Breckinridge.14

Col Breckinridge first commanded Marine Corps Schools from 2 July 1928 to 25 December 1929. Following service in China, BGen Breckinridge returned to Marine Corps Schools on 25 April 1932, with a reform agenda and the direction provided by his predecessor, the departing MajGen Commandant Lejeune:

There is a field in the conduct of war which can be properly covered only by Marines, and that is military operations connected with naval activities. Once ashore, there is no great difference between Army and Marine forces, but skillful execution of the vital operation of transfer from troopship to a safe position on the beach, of itself, justifies the maintenance of an efficient Marine Corps as an essential part of the naval establishment.

The design of courses at the Marine Corps Schools should, therefore, have in view that the Marine Corps is not an Army but an essential part of the Navy to be employed for naval purposes and that emphasis on the education of its officers should be placed on the requirements of those purposes.15

Under Breckinridge, the curriculum of Marine Corps Schools—including its Extension School which included courses for non-commissioned officers—was revised with fully one-half of the instruction focused on advance base operations. For a time, Breckinridge closed the senior course to allow the faculty to participate in creating doctrine. In 1934, a change in the school’s course titles to the Amphibious Warfare Junior Course and Amphibious Warfare Senior Course was pushed by Breckinridge to reflect better what was being taught to Marines at Marine Corps Schools.

The Marine Corps strategic Service concept would be further refined under Commandants Russell and Holcomb as they prepared for war in the Pacific. Marine Corps training and education would continue to evolve as part of force planning. Outside of Marine Corps Schools, specialized training was taking place in aviation, the employment of supporting weapons, logistics, and fleet operations. By 1939, the Marine Corps, although understaffed, was prepared to expand quickly and conduct offensive operations in the Pacific. Its training and education programs had been an effective part of a force planning strategy that successfully implemented the Marine Corps’ strategic concept.

The five years immediately following the end of the Second World War were exhausted in various schemes for defense unification, all of which envisioned a substantially reduced Marine Corps—if such a Corps continued to exist. Even within the Marine Corps, a special board, the Advance Base Problem Team at Marine Corps Schools reported that within an atomic age of warfare, the World War II type of amphibious assault was dead. LtCol Victor Krulak, a member of The Advance Base Problem Team, said the report voiced:

a prospective military philosophy. It consists of thinking in terms of the next war instead of the last. This means starting with ideas, when you have nothing more tangible, and developing them into concepts, procedures, and weapons for the future.16

The work begun by the Advance Base Problem Team remains interrupted and unfinished.

On 5 July 1950, elements of the U.S. Eighth Army engaged the North Korean Army at Osan. By August, the Eighth Army and its allies had been pushed south into the 230-kilometer-long Pusan Perimeter. On 2 August, the First Provisional Marine Brigade, led by BGen Edward Craig, landed at Pusan, entering combat on 7 August. Marines were once again deployed as part of the Army and the work begun by the Advance Base Problem Team was interrupted.

During the Korean War, “Marine Corps Schools, Camp Pendleton and MCAS El Toro carried the main burden of training … the Schools for turning out junior officers, and Pendleton and El Toro for preparing and processing the steady flow of replacements. … By the end of the war, 60 percent of the Corps had traveled that path … Conspicuous in the Pendleton cycle was the ordeal of cold-weather training.”17

A similar scenario would take place on 8 March 1965, when the 9th MAB landed at Da Nang, South Vietnam. Again, the Marines would be placed under Army control, and a steady flow of reinforcements followed by replacements would travel through Marine Corps Schools, Camp Pendleton, and MCAS El Toro. “Two and Thru” Marines dominated the force, spending six months in training, followed by thirteen months in Vietnam and 90 days in garrison before an early release. The work of the Advance Base Problem Team was now forgotten, and its members retired.

Thirty-five years (1945–1975) of a policy of defense unification, major deployments as part of an American land army, and a continuously transitory force changed the Marine Corps Service concept. While Marines would continue to make landings in Lebanon, the Dominican Republic, Cambodia, and elsewhere, the Corps as an organization was adrift, moving away from its Service strategic concept and advance base and amphibious heritage.

At the Marine Corps Development and Education Command, curriculums were revised to both confront and embrace these changes. At the Command and Staff College, its curriculum began to include topics “outside of its previous narrow Marine Corps and amphibious warfare focus.” Emphasis was now placed on statecraft, analysis of treaty obligations and restrictions, unified and specified commands, and the career potential of service “with departmental, combined, joint, and high-level Service organizations.”18 Envisioned as a sort of field-grade workshop, “a good portion of the student’s time will go into individual research projects, with corresponding free time for independent work written directly into the course syllabus.”19 “The Commandant of the Marine Corps also desired that the students be competitive; competitive not against each other, but against the high standards expected of a Marine officer.”20 Once again, the Corps was adrift with an unclear strategic concept, as was reflected in its training and education.

As the Marine Corps struggled to regain a Service concept other than that of the Nation’s better-prepared “second land army,” two visionary leaders were emerging. At Fleet Marine Forces Pacific, LtGen Louis Wilson was loudly arguing for modernization, insisting the Marine Corps should be a force in readiness—responsive and mobile while maintaining fast-moving, hard-hitting, seabased, air-ground task forces. In the same time frame, BGen Alfred Gray was changing Marine Corps training to emphasize large-scale maneuvers in desert and cold-weather environments. Both Wilson and Gray were redefining the Marine Corps strategic Service concept, but Gen Gray would take it the furthest, publishing a statement concerning service philosophy that became doctrine (FMFM 1, Warfighting). Warfighting provided a Service philosophy, but it fell short of providing a strategic concept for the Corps.

While the Marine Corps likes to tie the creation of Marine Corps University in 1989 to the publication of Warfighting in that same year, Marine Corps University is actually an end-product of defense unification as expressed in the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986. Goldwater-Nichols itself was a congressional reaction to the incessant inter-Service rivalries of the previous century and the perceived military failures that were the result of these rivalries.

Goldwater-Nichols sought to replace each Service’s strategic concept with a DOD-wide, Joint Services strategic concept (“joint” becoming the operative word replacing “unified”). Much of Goldwater-Nichols focused on the effective management of military officers, and section 663 (Education) contained additional requirements specifically related to “Joint Professional Military Education (JPME).” One of these requirements was a “review of service schools’ curricula to strengthen the focus on joint matters and to ensure that graduates were adequately prepared for joint duty assignments.”21 The House Armed Services Committee panel on military education (the Skelton Panel) recommended that Phase I JPME be taught in service colleges with a follow-on, temporary, Phase II taught at the Armed Forces Staff College (AFSC).22 Congress integrated this recommendation into the Fiscal Year 1990–1991 National Defense Authorization Act as a statement of congressional policy.23 In follow-up inducements to encourage attendance, Congress authorized the offering of accredited master’s degrees and more flexibility in follow-on assignments. Marine Corps University is a direct outgrowth of a congressionally mandated, Joint Services’ strategic concept, and funding earmarked to effect that joint concept.

Military education and training do not take place in a vacuum. Rather, both are elements in a force planning strategy that implements the Service’s strategic concept. The development of such a Service strategic concept has been hampered by two factors. The first is the extraordinary success Marine officers have enjoyed in rising to the top of the DOD unified command structure. In many ways, Marines have far exceeded their counterparts. Finding a Service strategic concept will require general officers willing to forgo the career opportunities “with departmental, combined, joint, and high-level Service organizations” Goldwater-Nichols jointness has provided in favor of leading Marines. The other factor is once again Marines have been deployed for an extended period as part of an American land army.

As the Armed Forces regroup from the decades-long Global War on Terror, the JPME concept has come under increased scrutiny and criticism. On 5 February 2019, the Secretary of the Navy announced decisions and immediate actions resulting from the department-level, department-wide, Education for Seapower study. This memorandum called for the refocusing of Navy and Marine Corps education and training on warfighting capabilities, naval war‑

fighting, and the consolidation of the department’s education programs into a single Naval University System with departmental education and student selection standards. It also directed a review of JPME with recommendations for changes to make naval JPME more relevant to naval careers and the “unique, expeditionary-centric, forward operational requirements of the Navy-Marine Corps team.”24

As has been discussed within the Gazette, controversy surrounds the formulation of a Marine Corps strategic concept and the strategic force plan to implement that concept. EABO, as a strategic concept continues to be challenged by advocates for a Marine Corps focused on extended land operations in conjunction with the Army. This focus on supporting Army operations has critics not only within the Marine Corps but also within the Air Force, Navy, and Pentagon. For the time being, this lack of an accepted Service concept and force plan makes the design of effective training and education impossible. However, this might be the proper time for Marine Corps Schools (i.e. Marine Corps University) to undertake the challenge of the 1950s Advance Base Problem Team to start with ideas, when you have nothing more tangible, and develop them into concepts, procedures, and weapons for the future.

>Dr. Doyle was in federal service for 22 years including 9 years in the Marine Corps, resigning as a CWO2 to accept a civilian appointment within the DOD as a Supervising Academic Programs Officer. As a National Guardsman, he spent 32 months of active duty as the Operations Sergeant of a Special Forces Battalion. Following federal service, Dr. Doyle has been employed as a university executive. His professional military education includes the Amphibious Warfare School (Extension) and the Naval War College.

Notes

1. The strategic concept is defined by the Service’s roles or purposes in implementing national policy and must answer the question: What function does the Service perform that obligates the nation to assume responsibility for its maintenance and continuation? Security, Strategy, and Forces Faculty, Strategy and Force Planning (Newport: Naval War College, 2004).

2. Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1939).

3. Robert Debs Heinl Jr., Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corp 1775–1962, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Nautical and Aviation Pub. Co. of America, 1991); and Jack Shulimson, The Marine Corps Search for a Mission, 1880–1898 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993).

4. Contrary to an 1899 Act of Congress, with the Class of 1896 the Navy Academy refused to graduate Marine Corps officers. This would continue until 1914. See Soldiers of the Sea.

5. In January 1909, the School of Application relocated to Marine Barracks, Port Royal (now Parris Island).

6. Pauline M. Shanks Kaurin, “Professional Military Education: What Is It Good For?” The Strategy Bridge, June 22, 2017, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2017/6/22/professional-military-education-what-is-it-good-for.

7. Search for a Mission.

8. Semper Fidelis; “Report on Marine Corps Duplication of Effort Between Army and Navy,” 17 December 1932, Gray Research Center, Archives Branch, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA.

9. LtCol C.H. Metcalf, “The Marine Corps and the Changing Caribbean Policy,” Marine Corps Gazette 21, No. 3 (1937); and Edwin N. McClellan, “American Marines in Nicaragua,” Marine Corps Gazette 6, No. 2. (1921).

10. MCI and ICS remained important sources of education and training for Marines into the 1970s. The author of this article completed ICS’ three-year course on public accounting while an enlisted Marine, passing the qualifying exam for state licensure as a public accountant.

11. John J. Pershing, General Pershing’s Official Story of the American Expeditionary Forces in France (New York: Sun Sales Corp, 1919); and Edwin N. McCellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1920).

12. Senior School Syllabi, Schedules, Synopsis, Regulations, Courses 1939–1970 from “History of the Field Officers’ School.” Source unknown.

13. Ibid.

14. See Dion Williams, “Marine Corps Training,” Marine Corps Gazette 10, No. 3 (1925; Dion Williams); “Fleet Landing Force,” Marine Corps Gazette 11, No. 2 (1926 and Dion Williams); “The Education of a Marine Officer,” Marine Corps Gazette 18, No. 2 (1933).

15. Memorandum from the MajGen Commandant to BGen Randolph Berkley, “Report of Board, Copy Attached,” 13 May 1931, “Marine Corps Schools, 1930–34,” folder 1. Marine Corps Research Center, Marine Corps University.

16. Marine Corps Historical Branch Interview with Col V. H. Krulak on November 18, 1953.

17. Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corps 1775–1962.

18. Donald F. Bittner, Curriculum Evolution, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, 1920–1988, (Washington, DC: History and Museum Division, Headquarters Marine Corps 1988). PCN 19000316900 Curriculum Evolution Marine Corps Command and Staff College 1920–1988 (marines.mil).

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, Report of the Panel on Military Education of the One-Hundredth Congress, committee print, 100th Cong., 1st sess., April 21, 1989 (Washington: GPO, 1989).

22. Ibid.

23. Section 1123, P.L. 101–189, November 29, 1989. This legislation was codified as a footnote to Section 663, of Title 10 United States Code.

24. Secretary of the Navy Memorandum, Education for Seapower Decisions and Immediate Actions, (Washington, DC: 2019).