Prospects for Ukraine in 2024–2027

The Road to Here

Three years into the Ukraine War, it is worth recalling the breathless American and European estimates of Ukrainian collapse, including from then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley and President Joseph Biden.1 Germany and France reacted with a combination of disbelief and wish-casting. Germany wholly discounted the prospects of an invasion.2 This explains the volte-face that characterised Olaf Scholz’s Zeitenwende speech on 27 February, when per American estimates, Russian troops should have been in Kyiv.3 A serious French intelligence failure did occur, but France clearly viewed Russian aggression as a political opportunity, hence Emmanuel Macron’s high-speed dashes to Moscow.4 It is a testament to Macron’s political instincts that Macron ultimately transformed France’s strategic position, making it a crucial rhetorical supporter of Kyiv’s independence and European alignment.5 American intelligence failure was more explicable in one respect: the Russian campaign plan did very nearly succeed.6 Russia’s multi-axis assault, intelligence preparation, and country-wide air campaign were designed to overwhelm Ukrainian decision making, allowing Russian paratroopers to hold Hostomel Airport and Russian armored forces to enter Kyiv by 25 February. The Ukrainian military would dissolve into disconnected units that could be encircled and mopped up over the coming weeks, while the Russian Special Services would begin population control measures to occupy the country. Russia’s failure stemmed partly from planning complexity, much like Graf Schlieffen’s planned single-wing envelopment of French forces. Graf Moltke did weaken the right wing of the envelopment, but his moves never actually decreased German combat power on the right.7 But despite its theoretical merits, the Germans ultimately failed because of a number of friction points, primarily the need to neutralize Liege in 48 hours, conduct a high-speed advance through France on foot, and maintain momentum despite encountering battles. In the event, the third factor spoiled the operational plan. Much like Valery Zaluzhny and Oleksandyr Syrskyi assembled a defense of Kyiv after the shock of war dissipated, Joffre’s decision to drive forward and disrupt the German advance broke the battlefield theory of victory.8

Western planners should have understood the dangers of an overwrought, hyper-intellectualized view of battlefield maneuver.9 Even though Russian forces had pushed over the Irpin River, the capital remained in a defensible position, particularly since the Desna River narrowed Russian options in the east and the Dnipro prevented direct assault from the north. Moreover, absent the intelligence penetration that enabled Russia’s southern advances, there was little chance of Russian forces rapidly capturing urban areas. Hence Kharkiv, Sumy, and Chernihiv all resisted despite Russian encirclement, pressuring Russian supply lines running and forcing Russia to choose between an assault on the capital or methodical high-casualty urban combat elsewhere.10

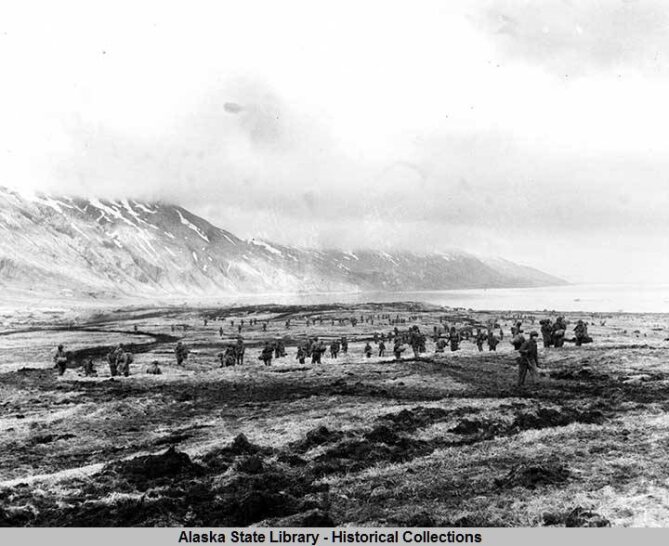

Unsurprisingly, 2022 was a year of operational movement. Most wars begin with a movement phase. Even the World War, a partial exception, proves the rule: the Phoney War from September 1939 to May 1940 was a strategic interlude, finally broken with a rapid maneuver campaign.11 Indeed, the Wehrmacht’s Fall Gelb is also illustrative in the Ukraine case.12 Ukraine and Russia have fought since 2014 over the Donbas, generating well-constructed, multi-layered fortifications along the line of contact.13 Assaulting these locations is difficult and costly, as Russia’s combat record demonstrates: it took Russia three months to capture Severodonetsk, six months to take Bakhmut, and six months of concerted combat after a decade of war to take Avdiivka. Much like the Wehrmacht’s General Staff in 1940, the Russian General Staff generated an aggressive operational plan that bypassed positional defenses. Yet, even the World War, a supposed maneuver war, had static stretches, including German and British minefield breaching operations, Soviet-German see-saw engagements around Moscow, brutal frontal assaults against trenches in Italy, and the costly U.S.-UK punch through the Siegfried Line.14

The Ukraine War’s positional-movement dynamics are similar. Ukraine staged three counteroffensives in 2022: a limited operation in Kharkiv that broke Russia’s siege, a broader Kharkiv operation that liberated 12,000 square kilometers of territory, and a more methodical operation in Kherson that threw Russian forces back over the Dnipro. Yet, since that point, there has been little to no movement, and not for lack of trying. Russia has executed two major offensives, a winter-spring 2022–2023 offensive that sought to capture Vuhledar and Bakhmut, and the winter 2023–2024 offensive against Avdiivka and Kupyansk. Neither has resulted in a major operational change, and both have imposed enormous losses on Russian forces. Ukraine, meanwhile, launched a major offensive June–September 2023, which failed to deliver operationally significant gains at obvious cost.

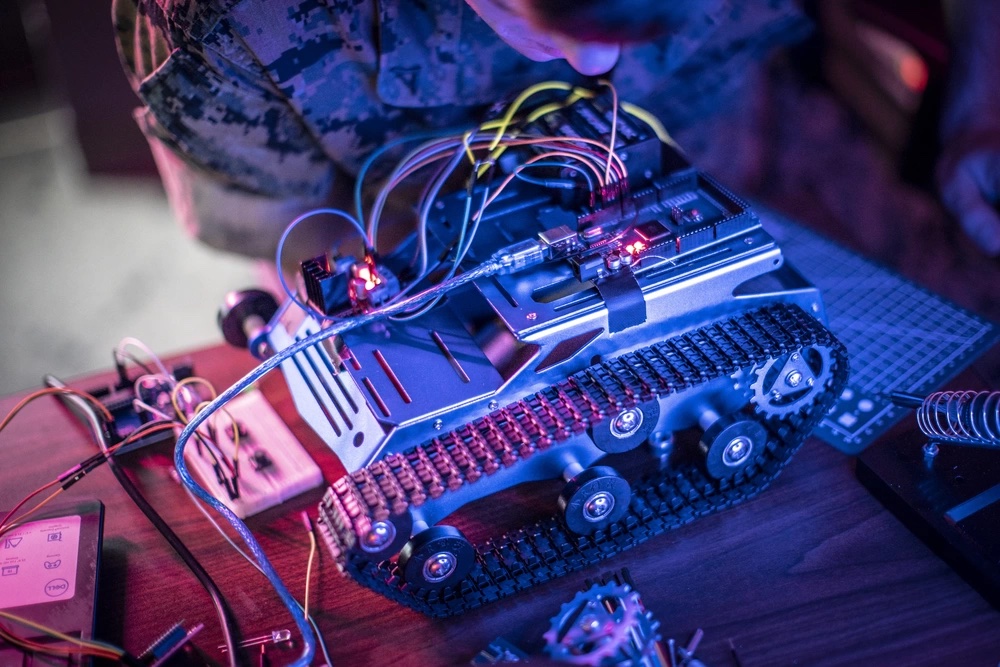

Western military and security officials repeatedly anonymously criticized Ukrainian strategic and operational decision making during the 2023 offensive.15 Ukraine, of course, largely disengaged with Western advice after the opening phase of its offensive, rapidly judging after the failure of its first breakthrough attempt against Robotyne that Western advice was irrelevant considering combat conditions.16 For example, the West has never fought a war under mutual air denial, limited but prised long-range strike capacity, and the acceleration and fusion of reconnaissance-strike and reconnaissance-fires complexes, all with a mass-mobilization army. Indeed, no Western country has executed a combined-arms breakthrough operation of the type Ukraine attempted since the World War or defended against one since the Vietnam War.

What, then, are the conditions that Ukraine faces? How can the advice and support effort be better calibrated to assist Ukrainian strategic planning and operational work? What might this tell us as a diagnostic for the battlefield and European policy over the next three years?

Positional Warfare

American advice and support missions have largely failed since Vietnam and notably failed in Iraq and Afghanistan.17 In the latter two cases, the United States refused to create a military organization that actually matched tactical and strategic requirements. The United States excels at Special Operations Forces (SOF) support. In Afghanistan and Iraq, U.S.-trained SOF were, and in the latter case remain, the backbone of state combat capacity.18 Ruthlessly deployed as assault infantry with extensive U.S. enabling capabilities behind them, local SOF tactically outfought any adversary. But the issue was strategic. Absent an American-sustained support network around them, Iraqi and Afghan SOFs lose combat effectiveness. In the Afghan case, this led to the regime’s collapse: absent air support, the Afghan National Army SOF were overwhelmed once the United States ended its sustainment mission.19

We arguably see a similar pattern in Ukraine. The closest contact between the U.S. military and the Ukrainian military prior to February 2022 came in SOF training missions.20 U.S. operators have spoken since 2022 of their lack of surprise at Ukrainian success—their view of the Ukrainian military, for bureaucratic reasons, was never transmitted to higher command or to net assessment and combat forecasting teams.21

Yet, bureaucracy alone does not explain the shortcomings of American and allied perceptions of the Ukrainian-Russian military balance, or difficulties in the advice and support mission. Bureaucratic inertia matters: Western-trained Ukrainian soldiers did receive high-quality combat medical instruction, but their trainers, never having fought on a UAS-saturated battlefield, did not provide coherent tactical and operational guidance that applied to the Ukrainian battlefield.22

Understanding the gap between the American advice and support mission and the realities of the battlefield requires a return to military theory. Specifically, we need to understand the character of positional war, to which the Ukrainian battlefield has evolved, and from there, build out a series of analytical inferences and programmatic recommendations.

The recently relieved Valery Zaluzhny’s Economist piece last November offers a useful but incomplete starting point, particularly since he patterned his essay off Soviet military-theoretical models.23 His analysis centered upon the interlocking character of UAS, air defense, mines, electronic warfare, and counter-battery fire. When combined, they create a nasty problem for the attacker—dense minefields slow the attacker, persistent UAS surveillance identify attacking units rapidly while effective electronic disruption, counter-battery fire, and air defenses limit the offensive battlespace isolation. A breakthrough is possible with sufficient mass, but training and equipping that mass is difficult. Moreover, the combat power benefits of mass decline on the Ukrainian battlefield when massed forces are discovered and thereby attacked and destroyed, a reality Ukraine has amply demonstrated through its use of precision-guided munitions.

Zaluzhny’s piece is a relevant starting point because it identifies the fundamental positional logic of the Ukraine War. But Zaluzhny, to his detriment, never explicitly defines a positional war. This generates a significant difficulty since the term itself is not thoroughly defined elsewhere.

Anglo-American military thought often conflates position with attrition. Attrition, in turn, is charged with significant negative implications. A war of attrition is often contrasted with a war of maneuver. The former is an unsophisticated slugfest akin to that of the Great War’s Western Front, in which materiel production and political resilience outweigh factors of military command.24 The latter is a model of military art, akin to Napoleon’s campaigns, in which tactical skill and aggression combine to create real examples of strategic and operational leadership.

The American bias toward maneuver over attrition is odd considering American military history. The greatest U.S. supreme commanders of the 18th and 19th centuries, George Washington and Ulysses Grant, were both masterful attritional fighters. Washington’s genius was in the retreat. While better-trained and equipped British forces won major engagements, Washington executed multiple successful retreats that preserved the bulk of Colonial forces. This was undoubtedly an attritional approach: by wearing the enemy down, Washington created the conditions for a more equitable strategic balance. Grant, meanwhile, embraced the logic of attrition. His Overland Campaign involved constant pressure on Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, compelling it to give battle multiple times in just a few weeks, ultimately locking the Confederate forces into a brutal static war they could not win. William T. Sherman, the third great general of the American tradition, fought an equally attritional war in the Confederacy’s heartland, slicing it in half and destroying its war-making capacity through his March to the Sea and subsequent Carolinas Campaign.

Moreover, the American military tradition lacks, in several fundamental respects, the concept of strategy given the United States’ commanding economic capacity. With the partial exception of the War of 1812, the United States has never engaged in a conflict from a position of structural weakness. The Confederacy did take with it well-trained officers and U.S. cotton production, but the Union’s industrial-mercantile northeast gave it a dominant advantage. Imperial Spain in 1898 was decaying. In 1917 and 1941, the United States did face significant adversaries, but America held advantages in population, industrial production, and resource wealth. Hence Franklin Roosevelt’s fundamental supposition, prior to December 1941, that ultimately American policy was simply to engage in the fight given its natural advantages.

The American strategy is, therefore, logistics, the skill of translating industrial capacity and population into combat power, and subsequently sustaining forces during engagements. This is an all-to-often neglected aspect of military science. However, it does not provide the American military practitioner with great fodder for theoretical inquiry.

The American tradition largely reaches to its German counterpart for examples of tactical military excellence. This began immediately after the World War, with the U.S. Army’s rational insistence upon debriefing German armored officers. Samuel Huntington’s The Soldier and the State solidified the trend. It takes the Prussian-German General Staff as its modern civil-military model, viewing the military officer as a professional dedicated to the rational political control of violence.25

Tactically and operationally, American military art emphasizes initiative, aggression, and the application of superior firepower and simultaneity between armor, artillery, and airpower, today coupled with cyberspace operations to collapse enemy cohesion and win a rapid, decisive victory akin to DESERT STORM or IRAQI FREEDOM. The Marine Corps equally embraced maneuver warfare and arguably drove beyond the Army’s obsession with it by the 1990s.26

This view self-evidently embraces maneuver warfare for partly self-serving reasons. Maneuver engagements are expressions of true military skill, embodied by Patton, Guderian, or Rommel—but they also keep wars short, crucial for U.S. democracy. Moreover, U.S. political authorities, per Huntington’s model, provide general objectives, while the military identifies the most rational combat solution to the problem presented. The military commander becomes capable of challenging the political leader on ostensibly objective military grounds, thereby abdicating responsibility to understand the totality of the combat environment in a manner Clausewitz would find inexplicable.

Yet, the dichotomy between attrition and maneuver, while common in American and Western military thought, is unhelpful intellectually. For one, attrition is the basic state of conflict, both from combat realities and due to Clausewitz’s friction.27 For another, the maneuver paradigm has prevented American strategists from coherently linking ends and means. By overwhelmingly emphasizing American combat methods, U.S. maneuver warfare departs from the contextual factors, political and military, that actually color combat.

The Soviet tradition conceived of maneuver and attrition rather differently. Most valuable is the work of AA Svechin, the first—and arguably the most intellectually coherent—of Soviet theorists.28 His text Strategy counterposes not attrition and maneuver, but attrition and destruction, the latter being a form of war in which the object is the destruction of the enemy’s combat capacity in direct engagements, the former being any other way of prosecuting an armed conflict. Svechin’s point is to demonstrate the limited context under which a war of destruction may be waged.

Historical comparison in military arts is difficult, hence Clausewitz’s demand that analogy should be sought from cases near in time.29 War is a political phenomenon, hence its nature is by necessity fixed, as is the nature of politics. But the character of politics, namely the organization of the political unit and the sorts of political and economic technologies employed, change over time, as does the character of warfare. The period of late 18th and early 19th century warfare thus marked the high point of the destruction approach, exemplified by Napoleon. Army size greatly expanded by the late 18th century due to changes in political technology and sustainment, but communications and transportation limits meant that tactical engagements could retain a direct link to strategy. Moreover, the 18th and early 19th-century state was personalized and post-feudal, not bureaucratic. Napoleon could win transformational victories because his enemies, as sovereigns or near-sovereigns, commanded their forces in combat, creating a direct link between the tactical and the political. This explains Napoleon’s success at Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstadt, and Wagram: in each engagement, he defeated an enemy sovereign and was, therefore, able to impose a peace. By contrast, Napoleon’s ultimate defeats from 1812 to 1815 stemmed from his inability to generate political effects from tactical victory. Borodino lacked it, while even Napoleon’s victories during the German Campaign were never overwhelming enough to achieve political reverberations. Subsequent examples of tactical engagements with direct political effect do exist, namely the Prussian victory at Koniggratz and the German victory at Sedan. But there are obvious differences between these victories and that of Austerlitz and Wagram. For in neither case did defeat lead to immediate enemy capitulation. After Koniggratz, it took Bismarck’s restraint to end the war on favorable terms. The French fought on for a year after Sedan, despite Napoleon III’s abdication.

Svechin grasped that the Great War’s brutality was a result of this loss of the tactical-political link that dominated the age of linear tactics.30 The battlespace had expanded in width and depth, through a combination of societal mobilization, advances in communications, and the advent of indirect fire artillery to necessitate an organizing principle for combat well beyond that of individual engagements. The Prussian General Staff model did provide some help, particularly with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau’s political emphasis—an approach Prussian military genius Graf Moltke the Elder missed. However, the Prussian model did not successfully provide a logic for large-scale modern combat. Svechin’s objective was to demonstrate that, rather than emphasizing a decisive point and harmonizing all efforts toward that goal, modern war would typically be a societal contest of attrition in which victory would go to the side capable of winning the final engagement, not the first one.31

Svechin’s understanding of positional warfare is couched within these terms.32 All wars have either offensive or defensive aims, which often change through a conflict, as tactical actions have strategic reverberations that compel a shift in political goals. A positional war occurs when at least one side adopts, even if temporarily, defensive objectives and digs in, creating Western Front-style layered fortification systems. Although offensives remain possible, a well-constructed defense requires excellent planning to conduct a breakthrough and exploitation operation at a high cost to the attacker. We can see this logic in action during the Soviet offensives from 1943 to 1945, when the Soviets were able to maintain the operational momentum from Kursk to Berlin through the careful management of reserves and staging of attacks, thereby preventing the Wehrmacht from reconstituting a stable defensive line.

Svechin distinguishes between two types of positional offensives, those that are conducted still under positional conditions and those that break a positional war and return it to conditions of manoeuvre. His examples for the former include some of the highest-cost battles in human history, namely Verdun and the Somme.

Transforming a positional battlefield into a manoeuvre one therefore requires immense effort and careful planning. Svechin’s analysis is instructive on the conditions necessary to prepare a positional offensive. There are two fundamental mistakes a commander can make in a positional war. First, a positional commander can reduce strategic and operational questions to those of logistics, viewing the positional fight as a contest with a static adversary that hinges upon production. Positional combat does demand a materiel focus. Yet, war is a non-linear and human phenomenon, requiring focus on far more than just materiel factors.

Second, and more dangerously, a positional commander can retain an unwarranted commitment to the offensive. Under maneuver conditions, commanders often decline the offensive, falling back to positions in the hope of making an enemy fight on unfavorable ground. This impulse, in Svechin’s view, is often taken to the extreme, although there is some good sense in it: had Lee followed it during the Gettysburg Campaign, the Army of Northern Virginia might well have retreated with its forces intact and compelled the Army of the Potomac to follow. However, under positional conditions, the scale of planning, coordination, and sequencing necessary for a breakthrough demands preparation beyond a single engagement or scrap of ground. But positional commanders rapidly become wedded to the ground upon which they fight, creating a dynamic where each side leans on the other.33

Commanders maintain positions on unfavorable ground to use them for a future offensive, even if eminently defensible territory exists just a few hundred meters behind the current front line. Limited positional offensives can succeed with proper patience and planning to unpick an enemy defensive system. But positional conditions demand the careful accumulation of resources for an ultimate offensive, with force preservation and the limitation of adversary attrition being the tactical priority.

Attrition and Decision

The Ukraine War is locked in a positional phase, with fortifications dominating the battlefield. The question, however, is whether Ukraine or Russia has any prospect of breaking the war’s positional character or whether or not the contest will continue in this manner until external political factors compel one or both parties to change their strategic calculus and accept a settlement.

Russia and Ukraine face distinct geographic problems. Viewed purely economically, and bracketing diplomatic issues and political pressure, Ukraine could accept a peace that ceded most occupied territory to Russia. Prior to 2022, Ukraine had already moved much of its industrial production away from the Donbas. Russian gains do jeopardize both Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia, but Ukraine can shift production elsewhere. Moreover, Ukraine has successfully reopened the Odesa port and expanded its rail links to Romania, reducing its reliance upon Kherson and the Azov Sea ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk.

Russia, however, cannot conclude a peace in this fashion. It lacks a wide enough land corridor between the Donbas and Crimea to maintain coherent logistics under Ukrainian pressure, as the war has demonstrated in ample fashion. In the east, it lacks an anchor for defensive lines by virtue of geographic chance, as well as sufficient strategic depth. Ideally, the Oskil and Siverskyi Donbets would anchor the line in the north, while at minimum Slovyansk and Kramatorsk would anchor the line in the center.34 Ideally, Russia would push to the Dnipro, bisecting the country and establishing that as a long-term defensive shield from Ukrainian strikes in depth. Russia requires greater territorial gains to stabilize its strategic position, or it risks—much like from 2014 to 2022—facing an insoluble strategic problem that its regime seeks to solve through conquest.

Russia has clung to the tactical offensive with the exception of Sergei Surovikin’s command during late 2022 and the summer 2023 defense in the south. Russia’s offensive results have been remarkably poor—the Russian military has lost north of 300,000 men killed and wounded, has burned through nearly all of its high-end armored vehicle stocks, and has turned to North Korea and Iran to provide it with ammunition. The difficulty is that absent a long refit period, better command-and-control structures, and improved planning, Russia will struggle to conduct and exploit a major breakthrough despite its materiel superiority.

Svechin provides two points of additional reference for commanders in a positional, attritional war. This war is undoubtedly one of attrition for Ukraine, if not for Russia, since Ukraine is incapable, for political and strategic reasons, of conducting a destruction campaign.

First, in a war of attrition, the decisive point in a post-Clausewitzean sense does not exist. Svechin does not mean that Clausewitz’s center of gravity is irrelevant—as authentically understood, Clausewitz’s center of gravity is not a physical piece of ground, but the nexus between moral cohesion, political objectives, economic capacity, and military power.35 In an attrition campaign, it is exceptionally difficult to identify a specific decisive point, because the objective is the overthrow of the enemy’s system. Hence per Svechin, the conditions for a decisive point must be created over time.

Second, in a positional war, the most crucial element of planning and operational art is the ability to manipulate enemy reserves. Positional defenses are extraordinarily difficult to break. If they are to be broken, the enemy must be corroded over time, with his forces divided, placed off balance, and attrited cumulatively to enable a final, decisive breakthrough that transforms the character of the war into one of destruction, rather than attrition.

Prospects

2024 will be a year of defensive planning, fortifying, and attrition. Russian resources are finite, and more specifically, broader economic constraints will begin to impinge upon Russian planning. Hence a successful strategy from Ukraine and the West must use this year to build combat capacity in anticipation of actions in the future.

Russia’s strategy is to buy time and keep up pressure in anticipation of a Western unraveling. Yet, it seems increasingly unlikely that this will occur. Aid is stalled in the U.S. Congress due to a combination of politicking and moral absurdity, for which blame is unevenly but collectively distributed between the Biden administration, House Republicans, and Congressional Democrats. However, the European powers look to have finally woken up. Ukraine has secured defense pacts with the UK, France, and Germany, while Central and Eastern Europe and Scandinavia are aggressively expanding defense production. Even if the United States abandons Ukraine, expanding European support and declining American leverage make this unlikely to end the war.

Russia, however, has a ceasefire as its objective for obvious reasons. The Russian labor market is already extraordinarily tight and tightening daily with more losses in Ukraine and subsequent conscription for the war effort. Military product quality has dropped as a result. Moreover, much of Russian production is instead refurbishment from Soviet stockpiles. This is enough to keep Russia in the fight, to be sure, and an old tank or artillery piece is just as deadly if employed en masse. Yet, attrition is cumulative—additional stresses on the system will unravel it.

General mobilization in Russia would place the Kremlin in an increasingly insoluble bind, particularly in light of solidifying European support for Ukraine. Russia is unlikely to win the ground war absent a period of reorganization, planning, and stabilization. But accepting this would require reducing front-line pressure, all as Ukraine executes public drone attacks embarrassing to Putin. Hence the pressure must be maintained. However, this will demand greater mobilization—soon, given the sheer number of casualties Russia has taken. A mobilization will lead to another round of human and capital flight, squeezing an already tight labor market, and triggering another round of inflationary pressure.36 As the rouble depreciates, Russia will find it increasingly difficult to purchase foreign supplies, military and otherwise. This raises the odds of a domestic that Russia has continuously sought to prevent since February 2022. This crisis will destroy the state if left to fester long enough, demanding that Russia either win the war, a proposition beyond its capacity or pause the war, a move within its power if the Europeans do fragment.

Ukraine, meanwhile, must execute a well-organized active defense that inflicts severe casualties on Russia, forces it into a mobilization cycle, and maintains the pressure during that cycle to expand societal stress. Avdiivka is an example of this. Ukraine inflicted severe attrition upon Russian forces during the six-month engagement, committing several brigades, including 47 and 110 Mechanised Brigades, elements of 10 Mountain Assault Brigade, and other smaller units to the city’s defense, against a dozen Russian line brigades and regiments, likely a half-dozen territorial brigades, and a variety of Storm-Z units. The extraction from Avdiivka, conducted by the 3 Assault Brigade, came at a cost, including 200 stranded Ukrainian soldiers, while the 110 Mechanised Brigade in particular took a beating. But in return, Ukraine inflicted north of 30,000 casualties on the Russians, in exchange for around 6,000 Ukrainian dead and wounded—a rate of two Ukrainian brigades to around ten Russian brigades depending upon precise combat strength and combat medicine.

A slow, methodical defense during which Ukraine cedes ground in a careful, painstaking manner is the best way to inflict this degree of trauma upon the Russian military. Yet, the issue is a political one. Ukraine will lose more ground this year, as Russia hopes to press Ukraine back to Orikhiv in Zaporizhzhia Oblast and then take it, and drive Ukraine back over the Oskil in Kharkiv Oblast. Russia will trumpet every victory, especially in the lead-up to the November 2024 U.S. elections. It is up to Ukraine and its partners, in Washington and Europe, to cultivate the political will to recognize the reality of the battlefield.

Ukraine can win a positional war—if it fights smart.

>Mr. Halem is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science, Senior Fellow at Yorktown Institute, Senior Fellow in Defence and the London-based Policy Exchange, and Title VIII State Department Black Sea Fellow at the Middle East Institute. He holds an Master of Arts (Hons) in International Relations and Philosophy from the University of St Andrews, and an Master of Science in Political Theory from the London School of Economics.

Notes

1. Jacqui Heinrich and Adam Sabes, “Gen Milley Says Kyiv Could Fall Within 72 hours if Russia Decides to Invade Ukraine: Sources,” Fox News, February 5, 2022, https://www.foxnews.com/us/gen-milley-says-kyiv-could-fall-within-72-hours-if-russia-decides-to-invade-ukraine-sources; and John Bowden, “Biden Warned Ukraine’s President Kyiv Could Be ‘Sacked’ By Imminent Russian Invasion,” The Independent, January 28, 2022, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/biden-ukraine-kyiv-invasion-russian-troops-b2002442.html.

2. Michel Duclos, “War in Ukraine–France Needs to Reassess its Foreign Policy Options,” Institute Montaigne, June 8, 2022, https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/war-ukraine-france-needs-reassess-its-foreign-policy-options; Bernhard Blumenau, “How Russia’s Invasion Changed German Foreign Policy,” Chatham House, November 18, 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/11/how-russias-invasion-changed-german-foreign-policy; Justin Huggler, “Embarrassment as Head of German Intelligence Trapped in Ukraine after Failing to Foresee Invasion,” Telegraph, February 26, 2022, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/02/26/embarrassment-head-german-intelligence-trapped-ukraine-failing; and Laura Pitel, “Robert Habeck Adds to Criticism of German Intelligence Blunders,” Financial Times, August 24, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/cc0b1300-89fc-4df8-863b-f691e0aac758.

3. Bastian Gigerich and Ben Schreer, “Zeitenwende One Year On,” IISS, February 27, 2023, https://www.iiss.org/sv/online-analysis/online-analysis/2023/02/zeitenwende-one-year-on.

4. Maia de la Baume, “France Spooked By Intelligence Failures,” Politico, April 6, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-military-intelligence-failure-russia-invasion-ukraine; and Luke Harding, et al., “Macron Claims Putin Gave Him Personal Assurances on Ukraine,” The Guardian, February 8, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/08/macron-zelenskiy-ukraine-talks-moscow-denies-deal-to-de-escalate.

5. Office of the President of Ukraine, “Agreement on security cooperation between Ukraine and France,” Office of the President of Ukraine, February 16, 2024, https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/ugoda-pro-spivrobitnictvo-u-sferi-bezpeki-mizh-ukrayinoyu-ta-89005.

6. See Jack Watling, Oleksandr V. Danylyuk, and Nick Reynolds, Preliminary Lessons from Russia’s Unconventional Operations During the Russo-Ukrainian War, February 2022–February 2023 (RUSI: 2023).

7. Terence Zuber, “The Schieffen Plan Reconsidered,” War in History 6, No. 3 (1999).

8. Liam Collins, Michael Kofman, and John Spencer, “The Battle of Hostomel Airport: A Key Moment in Russia’s Defeat in Kyiv,” War on the Rocks, August 10, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/08/the-battle-of-hostomel-airport-a-key-moment-in-russias-defeat-in-kyiv.

9. Napoleon’s campaigns provide ample evidence of this reality, particularly his victory at Austerlitz. See Frederick W. Kagan, The End of the Old Order: Napoleon and Europe, 1801–1805 (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2007).

10. See ISW’s tactical updates, 3 March 2022–30 March 2022, for a fuller analysis of the predicament facing Russian forces in northern Ukraine.

11. Winson Churchill, The Second World War, Volume 1: The Gathering Storm (London: Cassell, 1949).

12. Ernest R. May, Strange Victory: Hitler’s Conquest of France (London: MacMillan, 2001).

13. The only English-language assessment of the Donbas War from a military viewpoint is the Ukrainian National Defence University’s assessment. See Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, The White Book of the Anti-Terrorist Operation in the East of Ukraine, 2014–2016 (Kyiv: 2016).

14. See William Schneck, Breaching the Devil’s Garden: The 6th New Zealand Brigade in Operation Lightfoot, the Second Battle of El Alamein (DTIC, 2005), accessed via: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA447540. Unfortunately, the only version of this study is the linked one, which has a number of formatting errors, rather than a full-text PDF. The 300-page appendix is accessible as a PDF, but the original study is not. David Glantz and Mary Glantz, Zhukov’s Greatest Defeat: The Red Army’s Epic Disaster in Operation Mars, 1942 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999); Ernest F. Fisher Jr., Cassino to the Alps (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1993); and Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1993).

15. Washington Post, “Miscalculations, Divisions Marked Offensive Planning by U.S., Ukraine,” Washington Post, December 4, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensive-us-planning-russia-war.

16. For another example of snide criticism, see John Hudson and Alex Horton, “U.S. Intelligence Says Ukraine Will Fail to Meet Offensive’s Key Goal,” Washington Post, August 17, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/08/17/ukraine-counteroffensive-melitopol.

17. Rachel Tecott Metz, “Why Security Assistance Often Fails,” Lawfare, April 23, 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/why-security-assistance-often-fails.

18. Jonathan Schroden, “Afghanistan’s Security Forces Versus the Taliban: A Net Assessment,” CTC Sentinel 14, No. 1 (2021); and David Witty, “The Iraqi Counter Terrorism Service,” Brookings, June 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-iraqi-counter-terrorism-service.

19. SIGAR, Why the Afghan Security Forces Collapsed (SIGAR, 2023).

20. Adrian Bonenberger, “Ukraine’s Military Pulled Itself Out of the Ruins of 2014,” Foreign Policy, May 9, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/09/ukraine-military-2014-russia-us-training.

21. See from the early war, Michael Lee, “The U.S. Army’s Green Berets Quietly Helped Tilt the Battlefield a Little Bit More Toward Ukraine,” Fox News, March 24, 2022, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/us-armys-green-berets-have-lasting-impact-on-fight-in-ukraine.

22. Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Stormbreak: Fighting Through Russian Defences in Ukraine’s 2023 Offensive,” RUSI, September 4, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/stormbreak-fighting-through-russian-defences-ukraines-2023-offensive.

23. Valery Zaluzhny, “Modern Positional War and How to Win It,” The Economist, November 1, 2023.

24. Pat Garrett and Frank Hoffman, “Maneuver Warfare Is Not Dead, But It Must Evolve,” USNI Proceedings 149, No. 11 (2023).

25. Samuel Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1957).

26. Antulio J. Echevarria II, War’s Logic: Strategic Thought and the American Way of War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

27. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret (trans) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974).

28. The edition of Svechin referenced is Alexander A. Svechin, Strategy, Kent D. Lee (editor) (East View Information Service, 1992). This edition is accessible as a PDF, but unfortunately it lacks page numbers. Section titles and subtitles are cited where appropriate to provide the reader with an idea of a specific quotation, although the interested reader will need to access the text independently to find the precise passage referenced.

29. On War.

30. Strategy.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. As of this writing, Russia is engaged in an offensive to throw Ukrainian forces back over the Oskil. See Riley Bailey and Fredrick W. Kagan with Nicole Wolkov and Christina Harward, “The Russian Winter-Spring 2024 Offensive Operation on the Kharkiv-Luhansk Axis,” Institute for the Study of War, February 21, 2024, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-winter-spring-2024-offensive-operation-kharkiv-luhansk-axis.

35. On War.

36. Anastasia Stognei and Polina Ivanova, “Russia’s War Economy Leaves Businesses Starved of Labour,” Financial Times, November 9, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/dc76f0bb-cae2-4a3a-b704-903d2fc59a96.