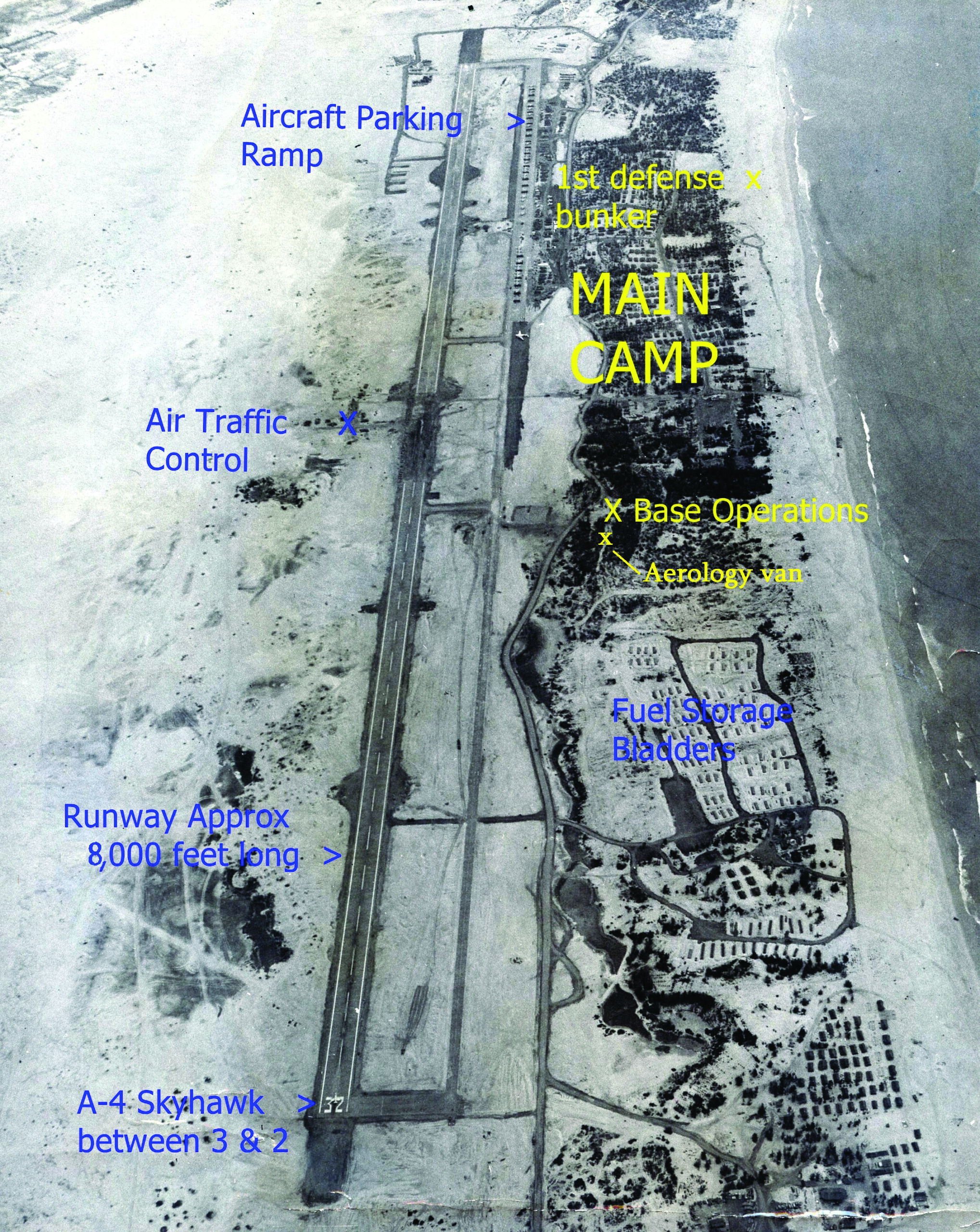

On June 1, 1965, four A-4 Skyhawks, led by Marine Air Group (MAG) 12 Commanding Officer, Colonel John Noble, landed around 8 a.m. on the first fully consolidated Short Airfield for Tactical Support (SATS) built and operated by the Marine Corps. It was an amazing feat: Within 30 days of boots on the ground, and with only 90 days’ advance notice, MAG-12 and the Navy’s Mobile Construction Battalion 10 built enough of “MCAS” Chu Lai to allow those four Skyhawks, followed shortly by another flight of A-4s, to refuel, arm and, four hours later, fly the first of thousands of sorties over the next several years.

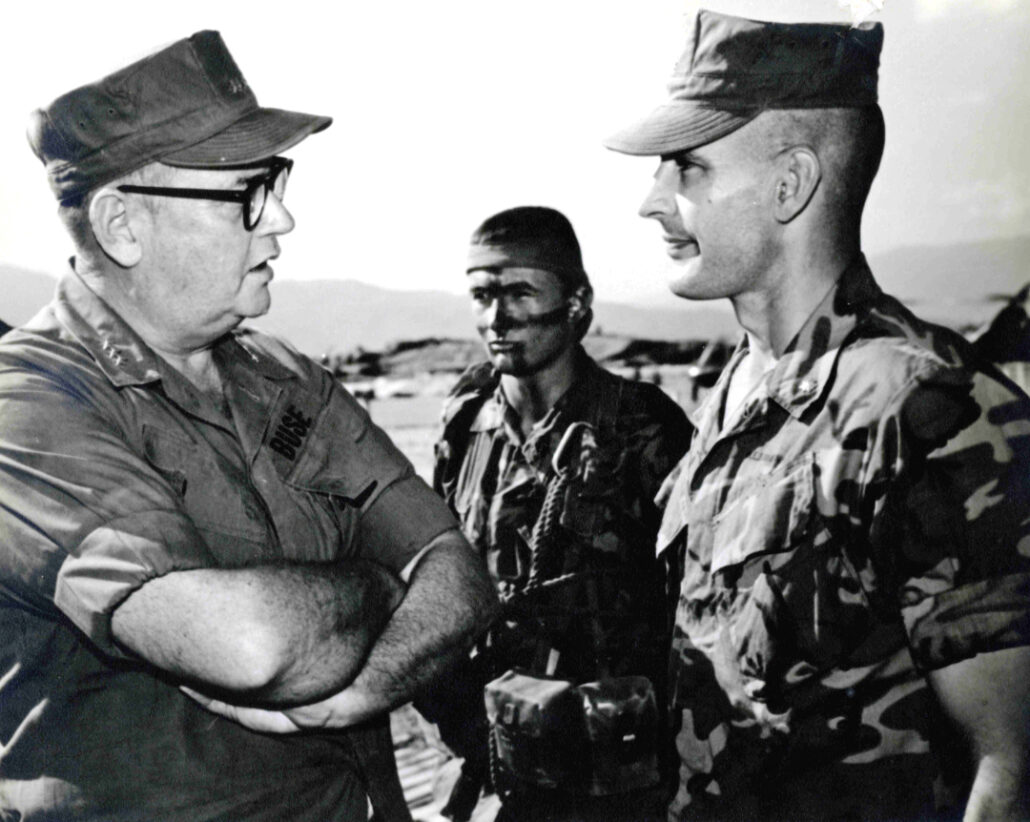

That spring, a brigade of Marines was sent to provide security at Da Nang Air Base. However, Lieutenant General Victor “Brute” Krulak, Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific (FMFPac), had been told by senior Air Force officers that Da Nang was at capacity and would not be available to support the Marines. A tentative approval was made on March 30 to establish another air base 57 miles south, which the officers told Krulak would take close to a year to build.

Little did they know, Krulak and members of his staff had already evaluated several scenarios. Although the area he had chosen for the base did not appear on their maps, Krulak dubbed the area “Chu Lai,” later explaining, “In order to settle the matter immediately, I had simply given [it] the Mandarin Chinese characters for my name.”

Based on that trip and assessment, Krulak, in so many words, assured the military brass that there would be no problem providing the needed air support in a timely manner. When asked by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara how long it would take, LtGen Krulak hesitated for a moment and then said, “25 days.”

The senior Air Force officers exclaimed that it couldn’t be done. However, as was typical of Marines’ foresight and creativity, they had begun working on a new approach that would allow this to happen nearly a decade earlier. It had already culminated in the testing of a prototype runway and taxiway surface and technical support systems at two different sites. One was built in California in 1962, and the other at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Va., in 1963.

In essence, it would be an aircraft carrier on land. Support systems would be prepackaged units of equipment in boxes, crates, vans and trailers—one for each wing—stored in strategically placed warehouses and when deployed, placed along the runway and taxiway surfaces. Navy Seabees and Marine combat and air base engineers would do the site prep, lay the surfaces and erect camps for personnel support services, resulting in a functioning Marine Corps air station in weeks rather than many months. Ultimately, it was decided that MAG-12 would take the lead, as its aircraft squadrons were more suited for the type of support and would have the greatest need for the airfield.

The History of the SATS

The concept of a SATS dates back decades prior. Its early days were rather simple, as those aircraft could land on almost any type of reasonably level and smooth surface. All that was needed beyond the field was some type of shelter from the weather to work on the aircraft and house the staff. As aircraft got heavier and faster, a suitable airfield became much more complex. World War II, especially the Pacific theater, saw the need for a quickly constructed and maintained airfield. The introduction of pierced steel (Marston) matting provided an interim step between graded dirt with compacted gravel and a permanent surface such as concrete, which took months to pour and cure. However, this did not eliminate the need for fairly long runways requiring conventional grading, and it was not suitable for larger and heavier aircraft.

Korea was the next major conflict to raise the bar on the need for an improved tactical airfield with the introduction of jet aircraft. Their sleeker design required a longer runway to obtain a faster air speed for the necessary lift on the wings. Those speeds also required a smoother runway surface.

There were three choices for commanders needing tactical air support immediately following Korea: to fly long distances from existing airfields, build a new airfield close to the needed air support or rely on an aircraft carrier if an ocean, sea or bay was close by. However, it could take upwards of a year to build such a facility, and carriers posed limitations regarding distance from the water and availability.

In the mid to late 1950s, the idea of the SATS emerged. The task for developing such an airfield was given to the Naval Air Engineering Station at Lakehurst, N.J. Basically, only four critical elements were needed to make this land-based aircraft carrier work: the runway, the taxiway and ramp areas, the catapult and arresting gear, and advanced technical support services.

The first was a smooth runway surface of suitable length. It was determined that a little more than the length of an aircraft carrier would be acceptable. Preliminary lengths were established in 1958 at between 2,000 and 3,000 feet. The Naval Mobile Construction Battalion (NMCB) Seabees could successfully provide an adequate level surface within a couple of weeks once earth-moving machines and personnel were in place, as they had plenty of experience doing that in the island hopping of World War II. The surface material was another matter. However, that was solved rather quickly with the development of AM-2 matting, a fabricated aluminum panel, 1 1/2 inches thick, with connecters so that the ends of the panels could be rotated and interlocked. Once interlocked, they could screw into an underlying base material. The panels came in sections 2 feet wide by 12 feet long, weighing 140 pounds. They could be easily handled by a four-man crew and support the weight and impact of any aircraft in the tactical aircraft inventory.

The next critical element was the catapult and arresting gear. The arresting gear was the easier of the two to develop. All Navy and Marine aircraft are equipped with a hook that drops down below the level of the wheels as they approach landing. The arresting gear on a carrier has a couple of very strong steel cables stretched across the deck just past the normal touchdown point of the aircraft. The tail hook drags the landing surface until it engages one of the cables. On early versions of aircraft, the cables zigzag back and forth between two pulleys on each side of the landing deck, separated by large hydraulic pistons. As the hook pulls the cables down the landing surface, the cables begin to shorten. The pistons resist compression and quickly slow the aircraft to a stop.

The mobile arresting gear for the early SATS used the same early technique, except the speed-reducing hydraulic pistons were mounted in a steel frame along each side of the runway and anchored securely to the ground.

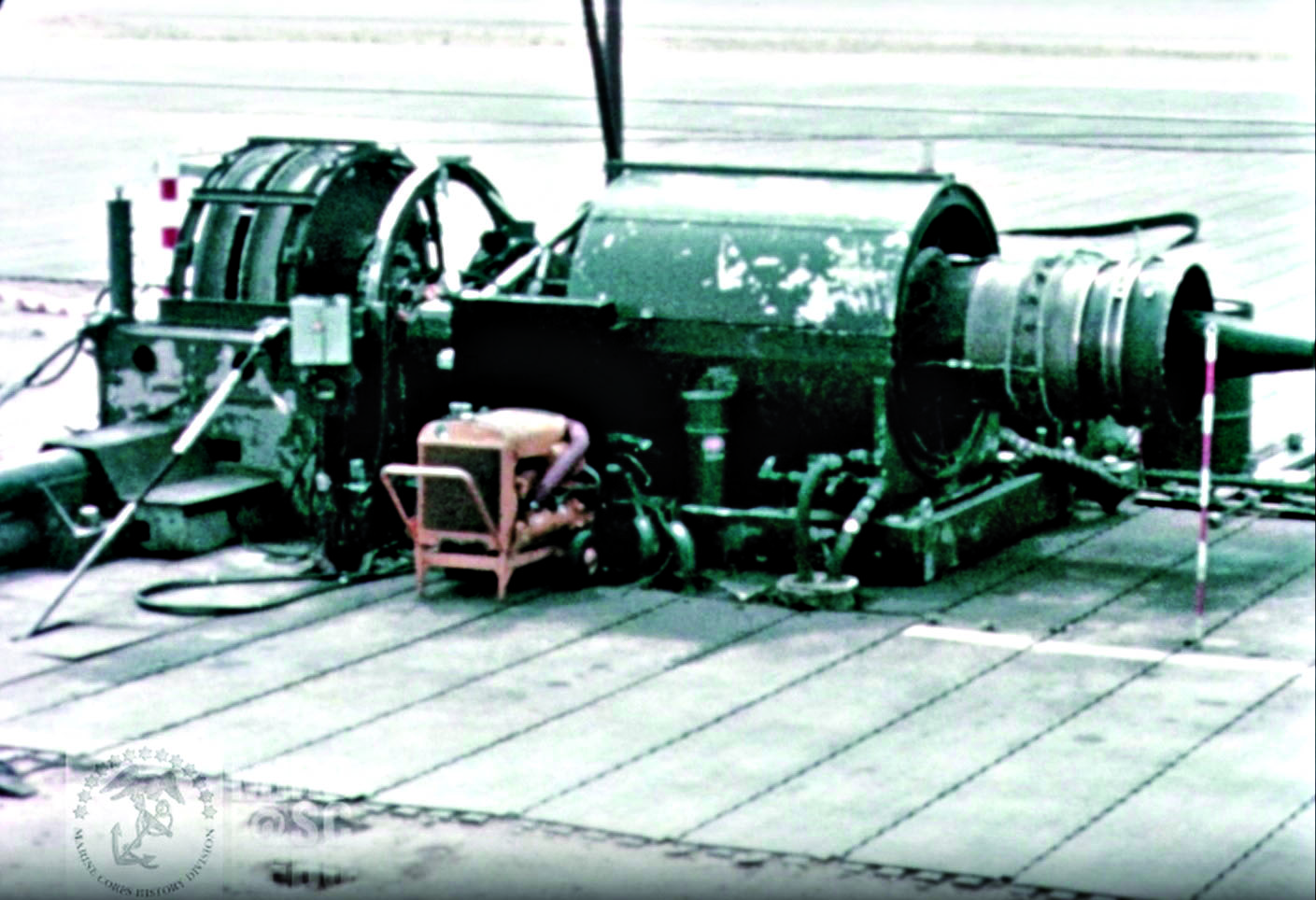

Carrier catapult systems used almost a reverse process of the arresting gear. At that time, large steam-driven pistons were located under the deck of the carrier at the departure end of the ship. The SATS catapult systems required a different approach, since there were no source of high-pressure steam and no provisions for equipment under the runway. The final design was to use a standard jet engine (GE J79) as a power source. An actual catapult system did not become available at Chu Lai until much later. In the meantime, aircraft at Chu Lai had to use jet-assisted takeoff bottles, attached to the rear sides of the aircraft.

The last of the four critical elements was the technical support required of modern aircraft and combat flight operations. Those items included, but were not limited to, air traffic control, communications, avionics repair, machine and mechanics shop, meteorological services and refueling. All these services were to be housed in self-contained or modular units.

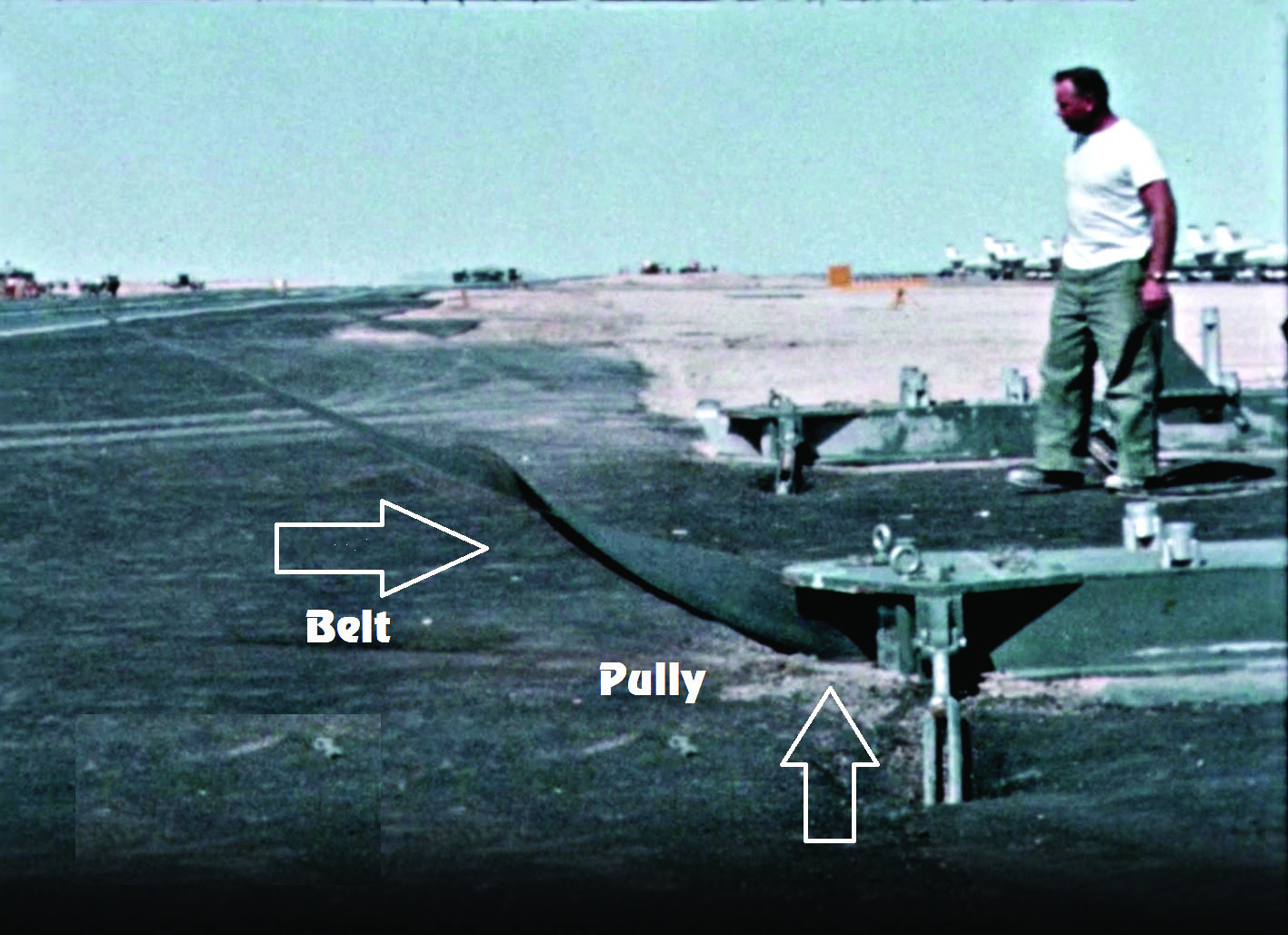

The SATS catapult system used a standard GE J79 jet engine (above) as its power source to drive the catapult. The engine was then linked to a high-tension catapult belt (right). While pilots initially used jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) bottles during the base’s first weeks, the installation of this engine-driven catapult system completed Chu Lai’s transformation. (Photos courtesy of Lawrence Krudwig)

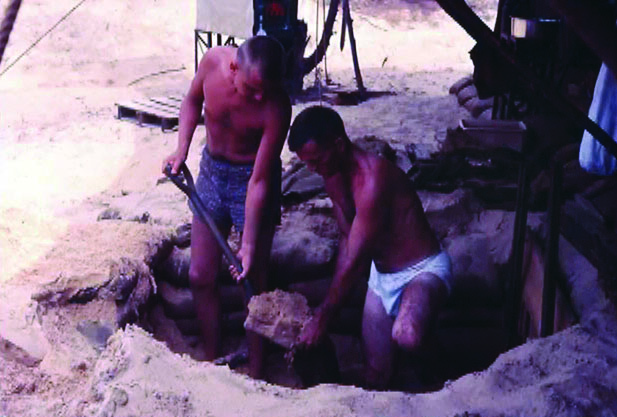

Marines dug this initial pit to tap into a freshwater source, allowing the unit to refill water buffaloes and expand into a network of pipes and water towers. (Courtesy of Lawrence Krudwig)

The Building of Chu Lai

A proposal approved on April 20 called for the MAG to be organized into six teams and transported in several landing ship, tank (LSTs) to Chu Lai in three phases. The first phase covered airfield construction, the installation of the SATS components including a basic camp layout, and the installation of certain camp facilities. The second phase was based on a fully operational airfield supporting one Marine attack squadron (VMA) with further campsite development to accommodate additional personnel and supporting functions. The third phase would bring the remainder of the MAG and an additional VMA. That plan was shortly revised to combine phases two and three. Marine Air Base Squadron (MABS) 12 had the lead on establishing the SATS and was initially scheduled to have use of four LSTs—the first two to embark phase one and the other two to follow in a couple of weeks with the remainder of the squadron.

With the ink not even dry on the plans and order, the first of many problems occurred.

Shortly before the first LST, Windham County (LST-1170), arrived on April 23 to transport troops to Chu Lai, the Navy informed 1st MAW and MAG-12 commanders that it would not be able to supply the needed LSTs or landing ships, dock (LSDs) and indicated others would not be immediately forthcoming. Loading the Windham County commenced at 6 a.m. on April 24 and proceeded satisfactorily until word was received that there would be only one LST available. This required changing all the embarkation plans to provide a maximum overall capacity on only one LST, as well as a larger construction effort. This required a complete rescheduling of manpower and materiel and the reorganizing of materiel already on the docks and in the adjacent warehouses. Reloading the Windham County was completed on April 27.

The NMCB’s transportation was entirely different, since their primary point of departure was composed of two sections from Port Hueneme and Point Mugu, Calif., following two separate exercises to Camp Kinser, Okinawa. On April 29, the NMCB, along with the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, left for Vietnam aboard two LSTs, an LSD and an attack cargo ship as part of the III Marine Expeditionary Force. The Marine brigade, acting as the advance element of a larger force, had the initial goal of hitting the beach, securing the area and acting as security for the construction and the air wing units soon to follow. They landed at 8 a.m. on May 7.

The first echelon of MAG-12 was comprised largely of personnel from MABS-12. They arrived at Chu Lai on May 7 and immediately began to unload to expedite a return to Iwakuni, Japan, to bring the remaining personnel and materiel. The personnel began the task to install and operate the facilities, such as shelters, food, water, sanitation, roads, transportation, communications, internal security and medical for the well-being of those who would be flying and maintaining the aircraft on the future base.

After setting up a basic camp, NMCB-10 began construction on May 9. While the location of the SATS facility was good for tactical purposes, heat and humidity were an issue. Official observations often recorded daytime temperatures in the upper 90s to low 100s with humidity values around 50%. Later runway temperatures were often at or above 115 degrees. Even more oppressive was late at night, when readings were in the low 90s with dew points in the 90s, resulting in humidity values at or near 100%. The weather conditions were manageable for crews by drinking plenty of water, taking salt tablets and pacing work sessions; however, the humidity still impacted productivity, equipment failures and aircraft performance.

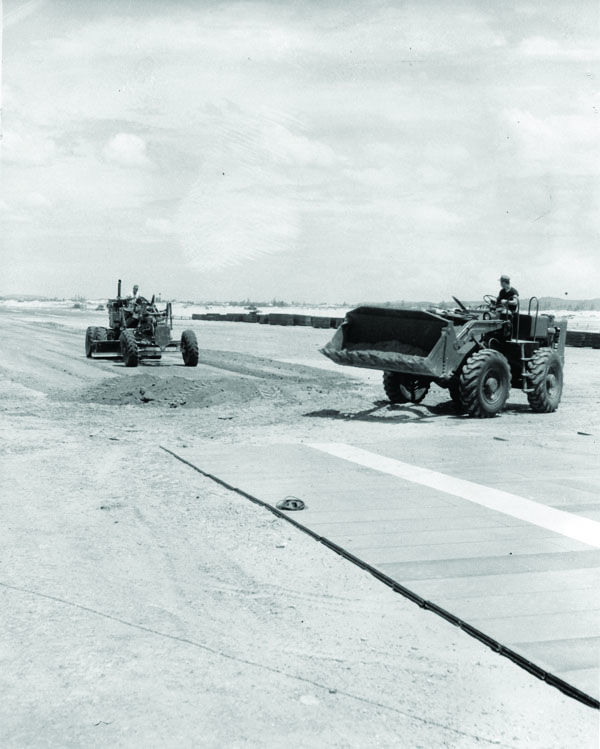

It was the sand, however, that would be a major obstacle to meeting their operational deadline. The area was roughly 100 square miles of scrub pine trees and sand that was so dry and fine, it could be described as powdery. Once a wheeled vehicle moved away from the wet sand and high tide, it would become stuck, and its wheels would just spin like in deep snow. On May 9, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Goode, the 1st MAW engineering officer, recorded, “My general impression of the entire day was that there was much wheel spinning, resulting in disorganization and little work accomplished, all compounded by the fact that three of the C.B. TD-24 tractors went out of commission.” The problems continued into the following day as more equipment fell victim to the heat and sand. With typical Navy and Marine creativity and the reprioritization of equipment, things began to fall back into place and back on schedule.

be offloaded directly from ships and moved inland.

(Photo courtesy of Lawrence Krudwig)

Over time, conditions got markedly better, as dirt was hauled in from the nearby hills to create a more extensive network of surfaced roads.

However, the sand also worked its way into bearings, clutches and other moving parts, causing premature failure. It blew into communications printers and electronic system switches and tuners. Air filters on motors required constant replacement. Because the sand was so dry and fine, it provided no suitable grounding conductive capability. This created a shock hazard to people and damage to improperly grounded equipment. The Marines needed more generators spread out at more distant locations and a three-wire feed for the hot, neutral and “ground” wires coming from and going back to the generators. They received less than half of the wires they needed, severely limiting the availability of electrical service.

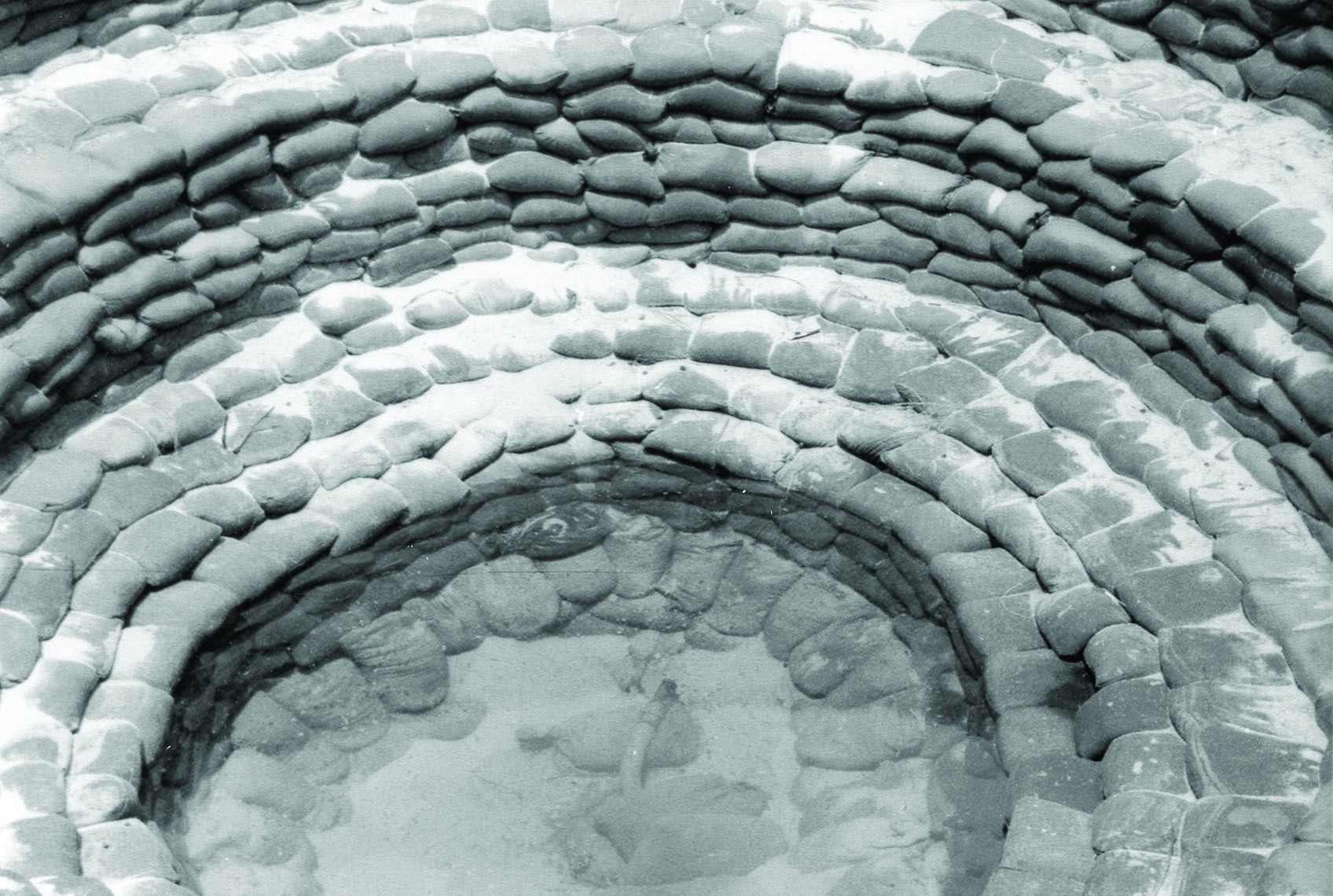

Sandbagged safety and security bunkers had to be dug by hand, but for every two shovels full that were thrown out of a hole, one shovel full trickled back in. Bunkers often had to be three to four times in diameter bigger than needed before the first row of sandbags could be put in place. The sand was equally problematic for personnel, as it got into everything from toothpaste and shaving cream to food and bedding.

According to unit diaries and other documents, only two days into excavation, things were going painfully slow. It became clear the sand was going to wreak havoc on this project. With a deadline of May 29, the construction battalion began working 24/7 moving dirt from a nearby hill, dumping and grading 64,500 cubic yards of the laterite. However, this approach would ultimately need ongoing and continued maintenance after any heavy rain, as the sand below would soften and collapse. Simultaneous with air-field construction, the servicemembers continued working on the basic camp facilities, security and communications.

One of the first orders of camp business was to find a local supply of fresh water. A pit was dug and after letting the par-ticulate settle to the bottom, the water was tested. It was free of

salt, requiring only chlorination. Marines began piping the main camp facilities and refilling water buffaloes, eventually digging an additional well and building a water tower.

Another immediate need was perimeter security. The Viet Cong used various methods to try to infiltrate the camp. And there were snipers, especially at night when any light was detectable in range. One of the first orders regarding security was that anyone’s authorized weapon was to never be more than an arm’s length away.

During the first weeks, sniper rounds started coming in from small fishing boats in the bay, beyond the effective range of the M14. A call was placed to the regimental landing team headquarters, and within minutes, an Ontos was coming down the beach in a cloud of dust. When an incoming round ricocheted off the anti-tank vehicle, the unit commander quickly spun around, lined up, fired a couple of tracer rounds and eliminated the threat.

There were other hazards as well. Local villagers and their children often approached the perimeter offering to sell items, especially cold drinks, to nearby personnel. Quick action by senior staff stopped such a practice.

The only known casualties were senior enlisted staff members. When they failed to make roll call the next morning, search parties scoured the area for days, never finding any evidence of their whereabouts. It was assumed they may have strayed too close to the perimeter during the night and were taken captive.

By May 16, enough runway surface had been prepared so that crews could begin laying the AM-2 matting. Six days later, 2,300 feet of matting had been laid.

As the first AM-2 mats were installed, the second echelon of personnel and materiel prepared to embark from Iwakuni with the remaining members of the MAG, MABS and flying squadrons, arriving on May 23. The unit diary noted that the midday temperature that day reached 117 degrees. VMA-311 and VMA-225 aircraft departed for NAS Cubi Point in the Philippines on May 26 to await the completion of the SATS runway and taxiway complex, scheduled for May 29.

The arriving ships were greeted by materiel that still sat on the beaches from the first deliveries, as well as an unstable causeway. Tracked vehicles were still needed to pull wheeled units off the beach. After all the ships were unloaded and departed, only the USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) remained. It had supported the initial brigade landing three weeks earlier using its UH-34D helicopters and was still on station continuing needed support. Work on the runways, taxiways and camp continued. By the end of the day on May 29, the runway was 3,545 feet with an accompanying taxiway and ramp area. All systems necessary to support combat flight operations were in place, and VMA-311 and 225 were ready at NAS Cubi Point. The only nemesis remaining was the weather. The remnants of a tropical storm made conditions unsafe for the Skyhawks to make the nearly 900-mile trip to the airstrip. Success would have to wait another day.

An Operational Air Station

On June 1, 1965, MCAS Chu Lai was officially declared operational. At 8 a.m., the first aircraft, the A-4 Skyhawk CE#6 piloted by Col Noble, touched down. The first VMA-311 aircraft touched down 30 minutes later. No time was wasted in arming and refueling four aircraft that would depart at 1:15 p.m. in support of an operation only six miles from the airfield. As work on the air station continued, air support missions went into full swing. At the end of June, MAG-12 aircraft had flown 303 missions and 969 sorties, delivering 2,338 bombs, 4,454 rockets and 58,471 20 mm rounds in support of infantry operations and enemy supply locations.

The month of June also saw a significant increase in camp facilities and improvements in creature comforts. The most noteworthy event was the completion of 8,000 feet of runway and adjacent taxiway on June 25. This virtually eliminated the need for jet-assisted takeoffs and landing arrests.

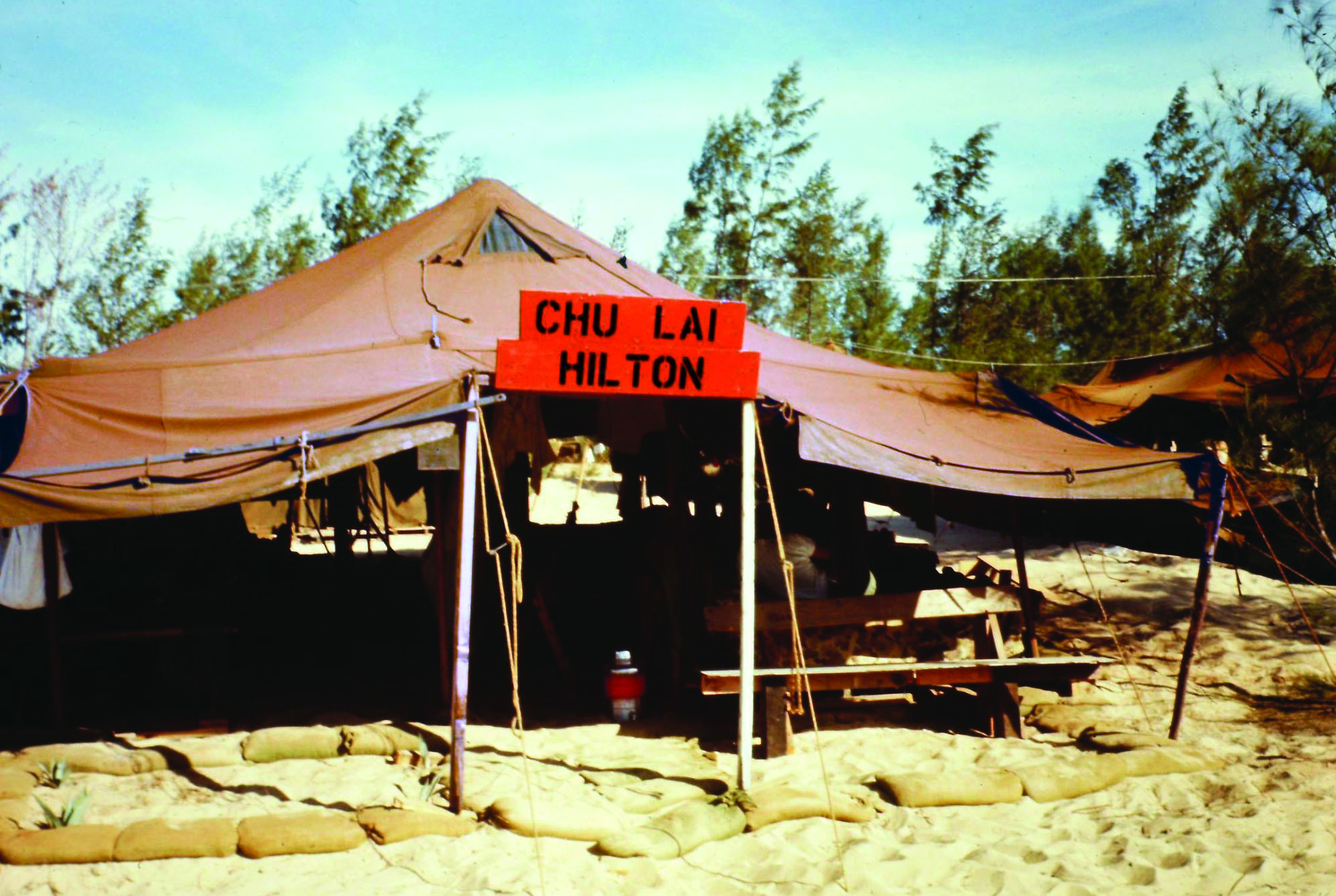

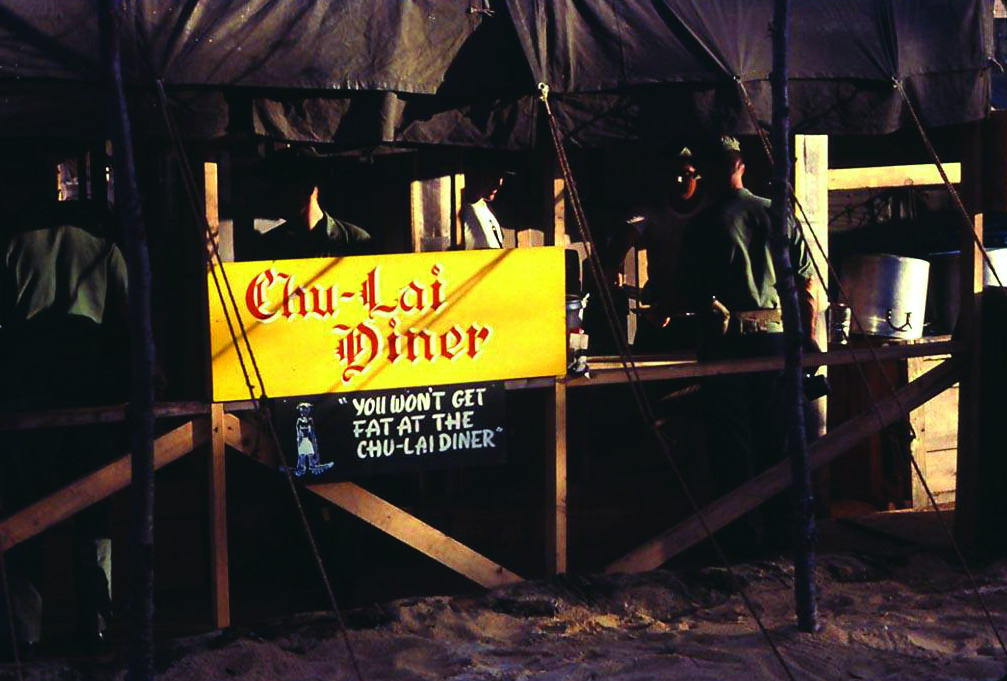

A mess hall, which had opened at the end of May, served two meals a day and obtained refrigerators, meaning more fresh meals were making their way to the troops. A post exchange was able to open on June 28, providing cold beverages. Recreation was most often achieved with a dip in the bay, which was as good as any expensive resort, and a primitive outdoor theater began showing films two days a week. The arrival of VMA-214 placed a greater demand on tent housing and sanitation, such as fixing hot showers and heads.

Electronic equipment continued to have periodic outages as the result of heat and dust. Air traffic control and radars were of most concern. High-vol-ume communications between major commands were still inadequate because of atmospheric issues caused by the heat.

As Chu Lai transitioned into an operational air station, the focus now shifted to sustaining and improving the lives of the personnel living there. (Courtesy of Lawrence Krudwig)

Although the brigade was getting bigger, the Marines were also becoming engaged in more offensive actions against the enemy. The MAG ordered the MABS to organize the equivalent of two rifle companies to take over base security, as there was a reinforced regiment of the NVA committed to throwing the Marines back into the sea. This would ultimately evolve into a mission on Aug. 18 called Operation Starlite, in an area only 12 miles south of the SATS. It would become the Corps’ first major operation in Vietnam, catching the NVA by surprise. The operation confirmed that the integration of close air support for ground operations was a sound and viable concept for the future of Marine operations.

The squadrons flew a combined total of 1,610 sorties in July and 1,656 in August, with aircraft availability at an amazing 76-79% under very harsh conditions. Ordnance delivery averaged approximately 1,000 tons per month. The first hangar was started on August 6, by which time other maintenance facilities had already been built, allowing for night repairs. Mess halls were in full operation, off-duty clubs were built, the tent city was taking on more features such as electricity, plywood floors, nearby potable water and laundry. The personnel were supplied with new utility uniforms, as the old-style cotton was literally rotting away.

The Marines had landed and were there to stay. Several months later, construction crews began the task of installing a new concrete runway to replace the matted one, a few hundred yards to the west. Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Baker, Commanding Officer of VMA-225, said of the original airstrip, “This aluminum field was as flat and even as a pool table, the smoothest, bump-free surface I ever flew from.”

Although some weeks later, a monsoon caused cavitation and created a slippery roller coaster effect, he went on to say, “But we flew!” The SATS concept had worked.

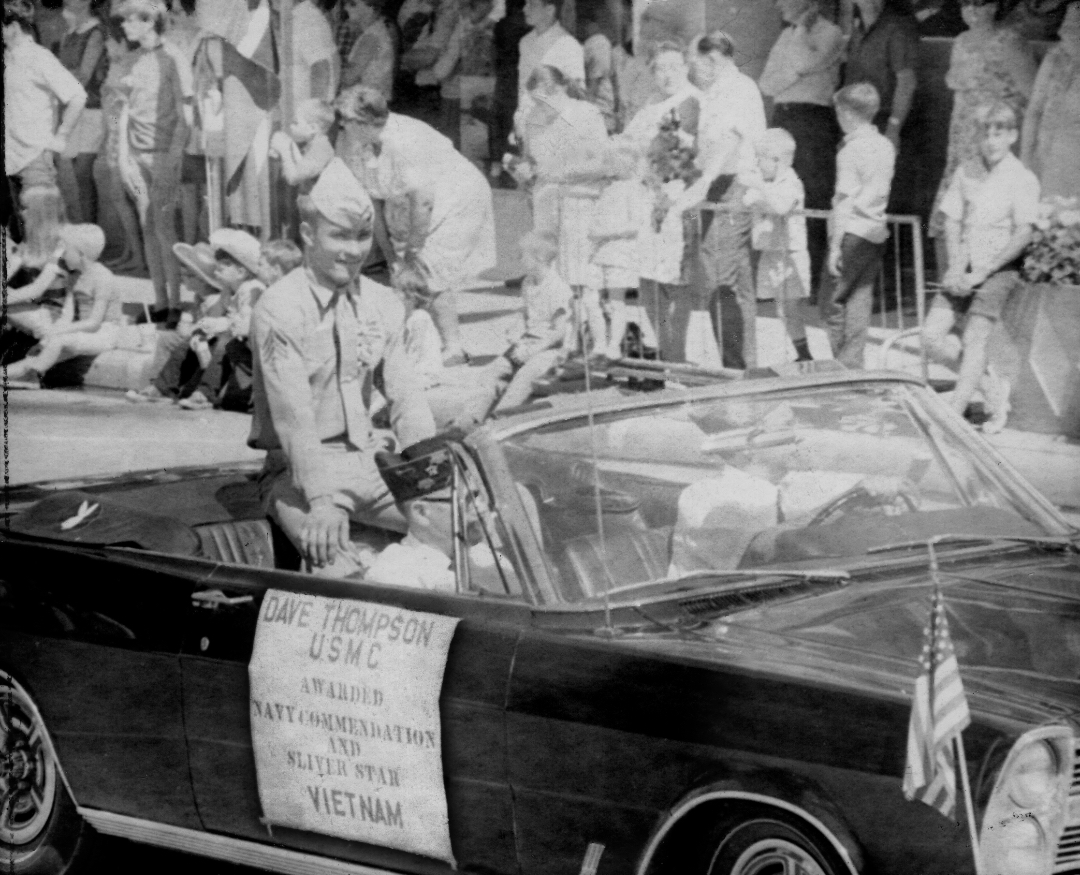

About the Author

Lawrence Krudwig is a Vietnam veteran who served as a corporal in the aerology sections of MAG-36 and MAG-12, deploying in 1965 to help establish the first SATS airfield at Chu Lai. Following his military service, he dedicated 37 years to the National Weather Service, earning numerous Department of Commerce medals for his work on national emergency alert systems.

He now lives in Missouri, where he remains active with the Marine Corps League and Missouri State University’s physics advisory board.

Enjoy this article?

Check out similar member exclusive articles on the MCA Archives:

Putting History Back Together: Telling The Story Of A Marine Helicopter Squadron Through A Rebuilt Huey

Leatherneck

By: Nancy S. Lichtman

SKYHAWK!

Leatherneck

August 1966

By: SSgt Steve Stibbens