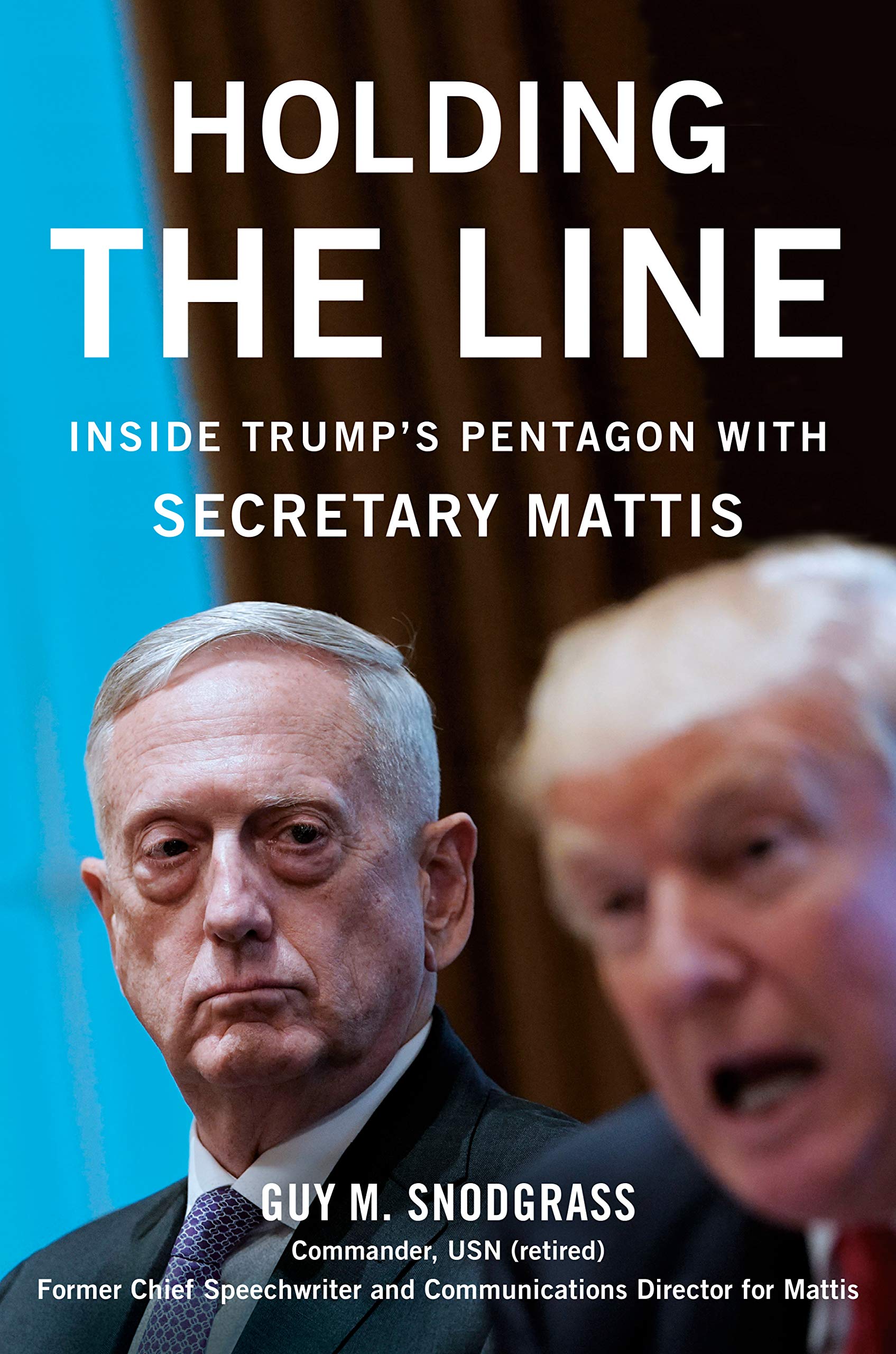

For the years spanning the late 20th and early 21st

centuries, former Secretary of Defense and retired Marine General James N.

Mattis stands as a preeminent exemplar of the Corps’ warfighting ethos: “He has

commanded Marines at all levels, from a rifle platoon to a [Marine

Expeditionary Force].”1 Capping a 40-year military career, he retired with four

stars, notwithstanding his willingness to speak his mind, frequently

challenging conventional wisdom and spurning political correctness. Marines

loved his plain-spoken manner, his affection for them and, above all, his

noteworthy combat leadership. The general public admired the authenticity of

this no-nonsense American warrior and treasured the quotable quips that made

occasional headlines.

Both in battle and the highest command and joint duty assignments, he honed natural leadership traits. He enriched his tactical and strategic insight and skills with intellectual curiosity about everything military: a passion reflected in his personal library of over 6,000 volumes and his claim, “[T]here’s no substitute for constant study to master one’s craft.” Upon retirement from the Corps in 2013, he became a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. He achieved a remarkable scholar-warrior reputation, neither exceeded nor even matched by anyone else of any rank or Service. In Call Sign Chaos, Mattis amplifies that stature.

When President Donald J. Trump selected Mattis as his first Secretary of Defense in January 2017, it came as no surprise that Congress overwhelmingly voted to waive a Federal law that would have otherwise disqualified him from that post for seven years after his military retirement. The only other such congressional waiver enabled five-star General of the Army George C. Marshall to become Defense Secretary in 1950. The Senate quickly confirmed Mattis by a vote of 98-1 (with only Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand voting no, and Sen. Jeff Sessions not voting while his appointment as Attorney General was pending).

Mattis served just two years as Secretary. On 20 December 2018, he submitted his resignation, which he attaches verbatim at the end of Call Sign Chaos. Mattis offers not a word to assess President Trump’s policies, character, or leadership. Instead, he promises that he is “old fashioned [and does not] write about sitting Presidents.” Almost exclusively, he draws upon his four decades as a Marine.

In this immediate runaway best-seller (briefly number one on the New York Times non-fiction list), Mattis promises “to convey the lessons [he] learned for those who might benefit, whether in the military or in civilian life.” The book’s three sections, “Direct Leadership,” “Executive Leadership,” and “Strategic Leadership,” connect his military career to the leadership theme. The story’s sole protagonist, Mattis links his professional autobiography to his own growth in leadership as his rank and responsibility rose.

He delivers “lessons” far beyond the prologue’s modest promise and outside the parameters of his legendary career and reputation as a Marine. He translates his military acumen and record into myriad memorable, fact-rich, teachable paragraphs that can resonate with current and aspiring military and civilian leaders. His exceptional combat instincts materialize in the direst of combat circumstances, portrayed in gripping accounts, capturing the urgency of those moments, and translating them into practical ways to think, lead, and prevail.

Although he shares jacket cover credit for authorship with Bing West, a formidable military author in his own right with a stellar background as a combat Marine and Assistant Secretary of Defense, this is Mattis’ first-person story from beginning to end. His voice carries the narrative, and his life history in the Corps and beyond personifies the “lessons … learned.” No doubt, West influences the riveting flow and readability of the narrative, but he remains behind the curtain; the only visible narrator is Mattis.

Call Sign Chaos will become a standard volume in curricula of America’s war colleges and career military schools at all levels. Despite the necessary military terminology and acronyms, his book will also strike chords for civilian university programs in politics, business, and leadership. For at least the present and near future, Call Sign Chaos should be America’s most authoritative and accessible primer on leadership in both military and civilian spheres.

During the three leadership phases described in Call Sign Chaos, he usually sees clearly through the fog of war, both in small, close engagements and in theater-wide strategic decisions and planning. He pleads to his share of mistakes, though, and forgives errors of others when done in a good faith effort to aggressively show initiative and accomplish the mission. He was ever ready to spar about decision making with superiors and subordinate commanders, yet always open to ideas from good thinkers of all ranks. As a Commanding General during the crucible of combat, he lauds recommendations to him by corporals or lieutenants that made decisive differences.

In crisis after crisis, he draws from a vast, self-made intellect—nurtured constantly by an insatiable desire to read and learn from others. With perhaps some unnecessary repetition, he admonishes his audience to do the same. His advice to read arises from experience, practice, and application:

Reading sheds light on the dark path ahead. By traveling into the past, I enhance my grasp of the present. I’m partial to studying Roman leaders and historians, from Marcus Aurelius and Scipio Africanus to Tacitus, whose grace under pressure and reflections on life can guide leaders today. I followed Caesar across Gaul. I marveled at how the plain prose of Grant and Sherman revealed the value of steely determination. E.B. Sledge, in With the Old Breed, wrote for generations of grunts when he described the fierce fighting on Okinawa and the bonds that bind men together in battle. Biographies of Roman generals and Native American leaders, of wartime political leaders and sergeants, and of strategic thinkers from Sun Tzu to Colin Gray have guided me through tough challenges. Eventually I collected several thousand books for my personal library. I read broadly and selected a few battles and areas where I was weak to study deeply.2

Mattis describes his early life only cursorily. His was a hardscrabble youth, marked by boredom in classrooms, reading at home, and regular hitchhiking starting at age thirteen. In college he “was a mediocre student with a partying attitude.” After underage drinking, a judge sentenced him to spend some weekends in jail. This setback awakened him to healthier pursuits. Following college, he earned his commission in 1972 as a second lieutenant. Mattis proves that a rise to the Marine Corps’ top echelon and beyond requires no privileged upbringing or unearned advantage.

Leadership is Mattis’ constant focus and touchstone. He eschews generalities, platitudes, or banalities—the banes of many textbooks. Instead, he demonstrates mastery of the art of war with dozens of riveting vignettes that include: planning for combat, arguing for or against specific tactics, and leading in combat. As a commander, his greatest affection is for his troops. Achingly, he laments the regular promotions that further removed him from direct supervision of, and camaraderie with, Marines engaged with the enemy: “I stayed in the Corps to be with the troops.”3 He lavishes praise, often by name, on fellow warfighters of all ranks who excelled on his watch.

He can be critical of commanders who, for him, did not measure up. He issues harsh, yet valid, assessments of U.S. Army GEN Tommy Franks who initially rejected deployment of Marines in Afghanistan because “[w]e don’t have access from the sea.” For Mattis, “[t]his was a classic example of being trapped by an outdated way of thinking. The Marines don’t need to be anywhere near a beach to land from ships.” According to Mattis, Franks inexplicably deprived the Marines of a clear opportunity to take out Osama bin Laden in the Tora Bora Mountains in December 2001, nearly ten years before Navy SEALs killed him in May 2011.

Mattis entertains as he teaches, demonstrates, and instructs. Intensity and pace leap from page to page and assignment to assignment. In his telling, large and small controversies among military and civilian leaders abound, and he was a principal actor in most of his examples. He weaves his mastery of warfare’s history, from antiquity to the present, into decision making at all ranks, from squad and platoon leaders, to combatant commanders, and the Commander-in-Chief.

Some critics contend that Mattis could be ruthless in the conduct of his leadership or complain that he is out-of-step with modern sensibilities, but history justifies his difficult personnel and operational decisions. He confronts head-on criticism for his colorful language and, far from apologetic, tackles critics with the same rhetorical gusto that he embraces with his actions on the ground.

As CG, 1st MarDiv, his relief of Colonel Joe Dowdy as commander of Regimental Combat Team 1 in 2003 was an unusual step. It was an abrupt removal of a distinguished and respected senior officer during combat operations in Iraq. Mattis’ explanation, however, makes sense. Without ever identifying Dowdy by name (even though the event and Dowdy’s name were publicized at the time), he depicts the colonel as overly fatigued and reluctant to carry out Mattis’ aggressive intent in the attack. During a face-to-face session with Mattis, Dowdy “expressed his heartfelt reluctance to lose any of his men by pushing at what might seem to be a reckless pace.” Because Dowdy’s honest admission contradicted the aggressive combat plan, Mattis fired him “on the spot,” even while acknowledging Dowdy as “a noble and capable officer who in past posts had performed superbly.”

In another example, he was NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander for Transformation in Norfolk and oversaw a staff of officers from many nations. He fired an unnamed foreign admiral working with him at because the admiral’s mistreatment of staff continued, even after Mattis’ counseling.

His frank assessment of political interference with military missions is persuasive. Mattis praises the positive and successful leadership of President George H. W. Bush, acknowledging how “he avoided sophomoric decisions like imposing a ceiling on the number of troops or setting a date when we would have to stop fighting and leave.” Moreover:

He approved of deploying overwhelming forces to compel the enemy’s withdrawal or swiftly end the war … He systematically gathered public support, congressional approval and UN agreement. He set a clear, limited end state and used diplomacy to pull together a military coalition that included allies we’d never fought alongside. He listened to opposing points of view and guided the preparations, without offending or excluding any stakeholder, while also holding firm to his strategic goal. Under his wise leadership, there was no mission creep.

He is critical of some aspects of President George W. Bush’s leadership in Iraq who held back the Marines in Fallujah, even though Mattis contended that they held an advantage that needed to be timely exploited. Bush overruled him, and Mattis “believed the President’s goal [to share combat responsibility with other nations] was idealistic and tragically misplaced.”

But he saves his harshest critiques for unwise military decisions by President Barack Obama, especially in the unwarranted and vacuum-creating withdrawal of all American troops from Iraq in 2011. He recites frustrating meetings with officials, including then-Vice President Joe Biden, and was perplexed at the level of ignorance about the likely consequences of a pullout—as foreseen by Mattis and many others in uniform.

His active duty career abruptly ended when he was fired as CG, U.S. Central Command. He recalls the circumstances and sets forth dissatisfaction with the poor quality of civilian military oversight at the end of 2012:

In December 2012, I received an unauthorized phone call telling me that in an hour, the Pentagon would be announcing my relief. I was leaving a region aflame and in disarray. The lack of an integrated regional strategy had left us adrift, and our friends confused. We were offering no leadership or direction. I left my post deeply disturbed that we had shaken our friends’ confidence and created vacuums that our adversaries would exploit.

I was disappointed and frustrated that policymakers all too often failed to deliver clear direction. And lacking a defined mission statement, I frequently didn’t know what I was expected to accomplish. As American naval strategist Alfred Mahan wrote, ‘If the strategy be wrong, the skill of the general on the battlefield, the valor of the soldier, the brilliancy of victory, however otherwise decisive, fail of their effect.’

Unfortunately, the predicted unraveling of Iraq occurred quickly as ISIS gained strength and geography, and U.S. troops had to return to the fight. Mattis makes a cogent case that self-inflicted strategic errors cost American lives and treasure and did grave injury to U.S. standing with other countries.

In addition, Obama’s failure to live up to his “red line” warning to the Assad regime in August 2012, wherein the former president stated that “a red line for us we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized,” profoundly diminished American credibility. A year later, when the Assad regime in Syria repeated its use of chemical weapons in defiance of Obama’s warning, the President authorized no retaliatory action. “This was a shot not heard around the world,” says Mattis, “Old friends in NATO and in the Pacific registered dismay and incredulity that America’s reputation had been seriously weakened as a credible security partner.”

At the same time, Mattis tempers a warrior’s credo with compassion for innocent victims of war, especially women and children caught up in or near the maelstrom of the battlefield. He rails, for instance, at “the egregious behavior of rogue guards at Abu Ghraib [which] had cost us the moral high ground.” Mattis’ leadership package emphasizes adherence to the law of war as a basic tenet. Even as he speaks often and straightforwardly about his quest to lawfully kill those enemy combatants who stand in the way of his Marines’ mission, and who fail to surrender, he never permits crossing professional or ethical lines. He cites two core principles that may appear to be paradoxical or contradictory to some. For Mattis, they are the essence of leadership in projecting deadly force in areas where civilians reside.

First, don’t stop. Don’t slow down, don’t create a traffic jam. Jab, feint, hit, and move, move, move.

Second, keep your honor clean. Thousands of homes, stores, stalls, and mud and concrete houses lined the roads. Terrified civilians would be in the line of fire. I made it clear that our division would do more than any unit in history to avoid civilian casualties.

The phrase, “no better friend, no worse enemy,” attributed to

Roman General Lucius Cornelius Sulla over 2,000 years ago, embraces a

fundamental truth for the ethical combatant, and it became Mattis’ calling

card.

Mattis challenges innumerable conventional wisdoms. He displays ingenuity and creativity in combat and invites those qualities in his subordinates; dispels rigid adherence to “doctrine” which he conceives as a startup point; and sees “commander’s intent” as a conceptual primer, not a constraint, for commanders who should understand what that intent is and be able to “seize fleeting opportunities under stress.”

Mattis often injects his famous wry sense of humor into a substantive message. He takes apart a mainstay of modern military (and civilian) classrooms and briefings—the PowerPoint:

PowerPoint is the scourge of critical thinking. It encourages fragmented logic by the briefer and passivity in the listener. Only a verbal narrative that logically connects a succinct problem statement using rational thinking can develop sound solutions. PowerPoint is excellent when displaying data; but it makes us stupid when applied to critical thinking.

Effective leadership must combine discerning, sometimes elusive, qualities for anyone in a position of high authority and responsibility. The ability to inspire others and to cause them to follow with trust and confidence requires a combination of talent, high character, integrity, perseverance, and hard work. A leader of troops in combat must also demonstrate personal courage and presence of mind in the most daunting circumstances. In Call Sign Chaos, Mattis powerfully demonstrates the qualities and actions that define leadership, but, perhaps most important for a work like his and West’s, he shows others what they, too, need to be leaders themselves.

Notes

1.

Col Chris Woodbridge, “Authentic Leadership:

An Interview with General James N. Mattis, USMC (Ret) and Francis J.

(Bing) West,” Marine Corps Gazette (Quantico,

VA: October 2019).

2.

See Call Sign Chaos,

Appendix B, which is Gen Mattis’ letter during the Iraq War elaborating on the

importance of professional reading. He also lists 58 of his “favorite books.”

3.

In a post-publication interview, Gen Mattis said, “Well there’s no doubt in my

mind the most enjoyable job is to be an Infantry Platoon Commander where the

physical toughness and the mental abilities are on full display to your troops.See “Authentic Leadership.”