Not by Technology Alone

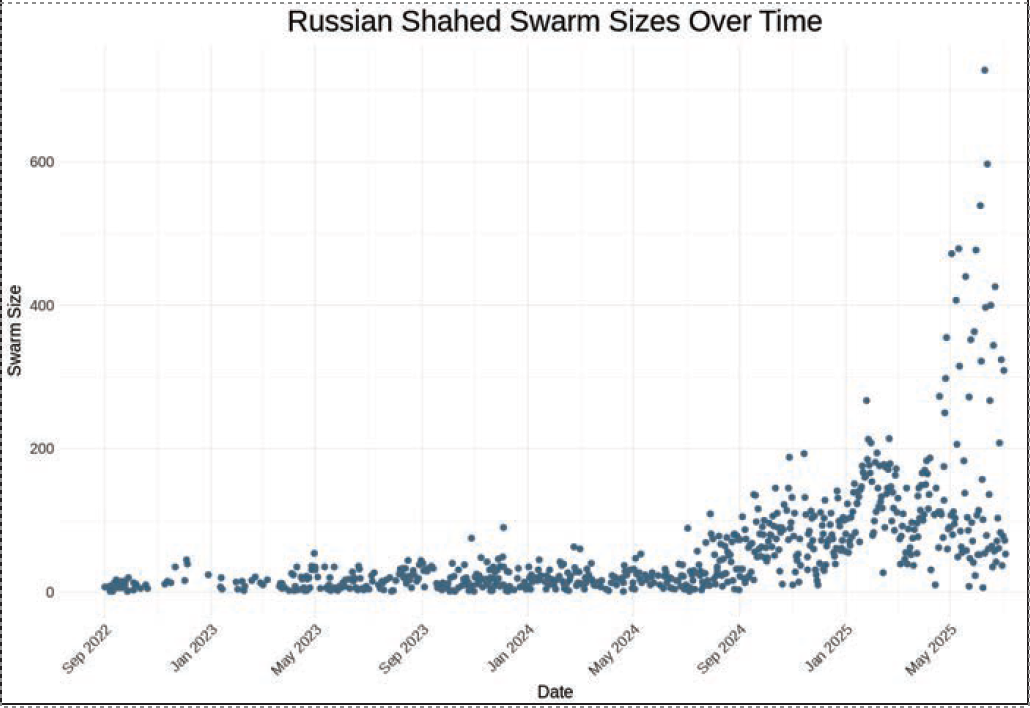

Drones have provided significant tactical advantages to both sides during the three years of brutal fighting in the Russo-Ukraine war. So, it is not surprising that uncrewed autonomous and first-person view drones and other uncrewed platforms are being heralded as the war-winning technology of the future.1 This euphoria was magnified by Ukraine’s June 2025 Operation SPIDERWEB, which masterfully employed drones to attack Russian air bases approximately 2,500 miles from the static front.2 This led some commentators to declare that the attack was Kiev’s Pearl Harbor.3

Moreover, two authors have proclaimed that the “drone era” is a military revolution and will remove the element of fear from war.4 This is an astonishing statement given that human beings fight wars to intentionally inflict violence on others out of “greed, fear, and ideology,” making it unlikely humans will disappear from tomorrow’s battlefields.5

This article contends that drones and artificial technology (AI) will continue to transform how future wars are fought; however, technology alone is unlikely to generate the required vic-tories to qualify as the next revolution in military affairs (RMA).

Evolution or Revolution?

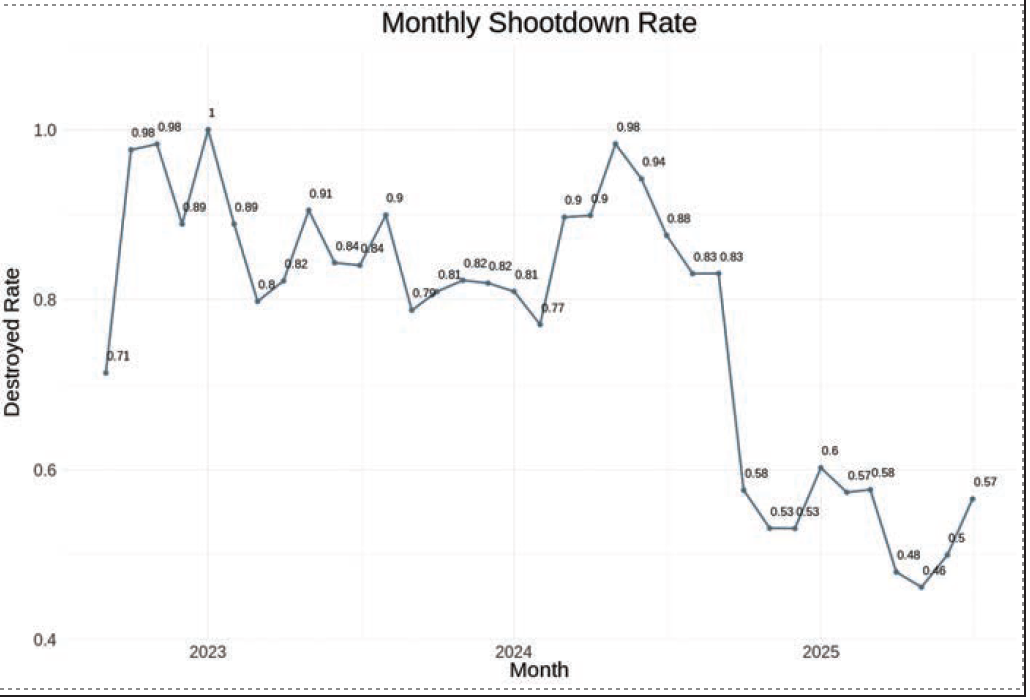

Drones have transformed the battlefield in Ukraine, but in an evolutionary rather than revolutionary fashion, as their impact falls short of the truly disruptive change that constitutes an RMA.6 Neither side has been able to decisively break through their opponent’s fixed, layered defenses and transition to sustained offensive operations necessary to achieve their respective political aims and “theories of victory.”7 A recent RUSI study concluded between 60–80 percent of Ukrainian first-person view, tactical drones failed to reach their target in 2024.8 Those that did were unable to destroy the armored vehicles they were trying to kill due to Russian electronic warfare jamming, poor weather, unfavorable terrain conditions, and operator error. A lack of Ukrainian artillery often prevented suppressive fires from being effectively employed with drones against Russian air defenses and dismounted soldiers protecting key targets. All told, first-person-view drones have proven most effective against enemy troops in the open. However, armies that disperse, conceal, maneuver with stealth, and deceive will likely lessen the effectiveness of adversary kill chains in the future.

… two authors have proclaimed that the “drone era” is a military revolution …

Technology + Operational Concepts + Organizational Adaptation = RMA

Revolutions in military affairs occur when a new technology is combined with innovative operational concepts and organizational adaptation to fundamentally alter the character and conduct of conflict.9 The RMAs dramatically increase the combat potential and military effectiveness of fighting forces relative to a specific adversary, but these three ingredients must be amalgamated before a true RMA is born.10

Revolutions in military affairs are rare occurrences—Andrew Krepinevich cites only ten since the 14th century.11 Nevertheless, premature pronouncements that a new RMA has arrived are not new. In 2004, Stephen Biddle cited six such examples: the inventions of dynamite, the machinegun, the naval torpedo, the airplane, strategic bombing, and the atom bomb.12 Biddle believed these new technologies led military thinkers of their day to overestimate the impact they would have on warfare.

This trend continues today and, on one level, it makes sense. War’s inherent brutality has long incentivized humans to seek short wars and “silver bullets” that can reduce its cost in casualties and national treasure. Moreover, the reliance on advanced technology has been a central pillar of the American Way of War since at least World War II, as the United States places greater emphasis on technology in planning and waging war than any other nation.13

Yet, in the context of the Russo-Ukraine War, drone performance has been exaggerated despite compelling evidence otherwise. Amos Fox argues that drones in protracted land campaigns, like Ukraine and Gaza, have proven strategically irrelevant given their inability to take or retake territory, hold ground, seal borders, and protect populations.14 Other studies question drone reliability and effectiveness.15 Thus, claims that drones have revolutionized the character of war deserve closer scrutiny.

Generating Leap-Ahead Combat Capabilities

As noted above, RMAs change the character of war because they generate an asymmetrical advantage in combat capabilities vis-à-vis one’s adversary. What is revolutionary is not the pace of change, but rather, the character of the change and the degree of overall improvement in military capabilities.16

Such improvement can occur absent new technology, as was the case with the 18th-century French “levee en masse” (i.e., forced conscription) that tripled the size of Napoleon’s Army in less than a year.17 It can also result from repurposing and imaginatively using old technology, as Germany did with tanks—first employed by the British in the 1917 World War I battle of Cambrai—by integrating armor with radio communications, airplanes, and mechanized infantry to generate a potent combined-arms team that became the blitzkrieg.18

Yet, it is important to acknowledge that the introduction of new technology is a key incubator that can alter the character of war, as witnessed with the precision-strike revolution that came of age in the 1991 Gulf War.19 Some three decades later, the precision strike RMA enabled the United States to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities in Operation MIDNIGHT HAMMER.20 But battlefield context matters, as it took eleven weeks of bombing from fourteen NATO nations (some 40,000 aircraft sorties flown) along with the threat of ground invasion during Operation ALLIED FORCE before Serb leader, Slobodan Milosevic, backed down.21

Coming of Age

In almost all cases, new technologies mature more slowly than military planners and operators desire. The 1972 Linebacker II bombing campaign against North Vietnam expended approximately the same number of laser-guided munitions as the 1991 Gulf War.22 The qualitative improvements that allowed the same number of munitions to be exponentially more effective than their forbearers took nearly two decades.

The same is true with ground-launched anti-tank weapons systems. What started in the late 1970s with the Dragon and family of wire-guided missile systems eventually matured into the “fire and forget” Javelin that proved so effective against Russian armor in 2022.23

… RMAs change the character of war because they generate an asymmetrical advantage in combat capabilities vis-à-vis one’s adversary.

Drones, too, have a long lineage that traces back to 1917–1918 when the British and American’s respectively, developed the Aerial Target and Kettering Bug pilotless aerial platforms.24 Yet, it was not until the Vietnam War that drones were deployed in relatively large numbers.

In sum, a lengthy maturation process ensues before new technologies, innovative warfighting concepts, and organizational adaptations successfully combine to ignite revolutionary, leap-ahead combat capabilities. This time-consuming process is not exclusively the fault of tech developers, engineers, and an unwieldy defense acquisition process. Rather, lengthy, but essential, military experimentation must also occur to provide the Services and Joint Force practical insights into how its concepts and organizational design should be adapted to effectively campaign with the new technologies.25

Maintaining Asymmetrical Advantage

The competitive asymmetrical advantages new technologies bring to warfare are fleeting. Being a “first mover” or early adopter of enhanced capabilities incentivizes competitors to counterbalance, especially if the new capabilities are widely proliferated.26

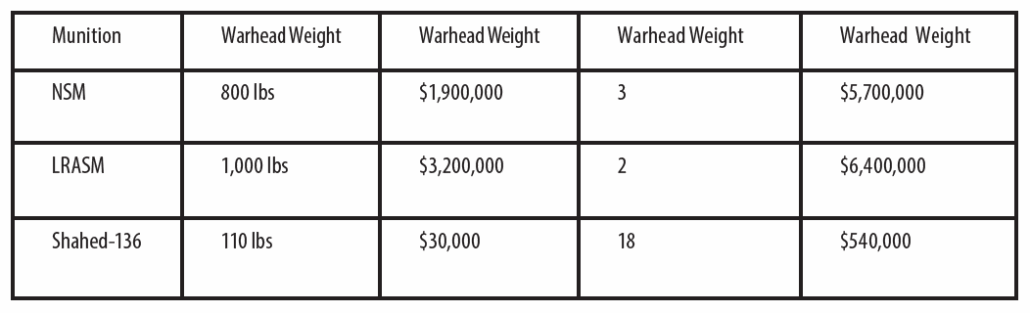

Today’s rapid diffusion of technology means smaller powers and non-state actors can easily and cheaply manufacture or commercially acquire drones, satellite imagery, global communications devices, and a host of other technologies for battlefield use. The Houthis recently demonstrated this with their drone attacks against Red Sea shipping.27 Thomas Mahnken describes this phenomenon as one of “emulation,” which will continue to erode, if not eliminate, the comparative asymmetrical advantage drones and other emerging technologies afford the U.S. military.28

When the barriers of emulation are too high, adversaries will attempt to develop countermeasures to thwart new combat methods.29 As an example, to offset U.S. firepower and mobility advantages in Iraq and Afghanistan, the enemy’s weapon of choice was the improvised explosive device (IED)—the legacy “boobytrap.”30 Decades earlier in Vietnam, the Viet Cong used the low-tech entrenching tool to turn the Cu Chi area outside of Saigon into 155 miles of underground tunnels and mini-subterranean cities to counter America’s air power advantage.31

Thus, smart adversaries will rapidly emulate or develop countermeasures to negate the asymmetrical advantages afforded by real or faux RMAs. In Ukraine, the world has watched this process play out in realtime, which makes the Russo-Ukraine conflict a revolution in adaptation war vice a universal RMA.32

Weighing the Risk of Military Innovation

Military innovation is a “balancing act between destroying traditional ways of war and creating new ones,” a gamble that risks losing more by abandoning legacy capabilities than is created with new innovations.33 Past, but flawed high-risk bets about the changing character of future wars include the development of British armored doctrine before World War II;34 the U.S. Air Force embracing the long-range nuclear bombing mission in place of close air support and air superiority competencies needed in the Korean War; and the U.S. Army restructuring itself into Pentomic formations to fight on a nuclear battlefield.35 According to Kendrick Kuo, in each case, militaries divested themselves of critical capabilities and competencies they needed in the next war.36

… prudent observers of modern war are right to question any technology being championed as a “war-winner”…

Fear of missing the next military revolution and being relegated to “second mover” status can seductively entice force planners to bet and invest in the wrong RMA. Sir Lawrence Freedman argues that Ukraine’s drone environment is context-specific and may not be germane to future battlefields that are not characterized by static front lines and slow-moving, long-range drones that have trouble penetrating well-defended targets—in need of more effective integration with other traditional military capabilities such as aircraft, armored vehicles, and artillery—to prove decisive.37

Freedman is not alone in his thinking, which makes it risky to adopt the drone tactics, techniques, and procedures from the stalemated Russo-Ukraine War as a perfect template for future conflicts.

The Pitfalls of Technological Determinism

Historians Williamson Murray and McGregor Knox believe the lessons of history demonstrate that technological superiority does not guarantee success in war.38 In World War II, U.S. materiel and technological dominance still required grueling battles across the Pacific to the Japanese homeland before an exhausted and starving adversary ultimately capitulated.39 More recently, technologically-backward states like North Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan denied the United States its war aims, notwithstanding the latter’s overwhelming firepower advantage.

Clausewitz argued that war is fundamentally a contest of human wills, which means there is more to war than simply “blowing up targets.”40 Ultimately, human factors such as leadership, training, discipline, and doctrine—not weapons—are the final arbiter of battlefield success or failure. Thus, underestimating the tenacity and staying power of a technologically inferior underdog comes with a high price tag.

Forward into the Unknown

Until the Russo-Ukrainian War ends, both sides will continue to rapidly adapt. Lessons observed during the war’s early years may provide new insights that will help inform how the United States and other nations transform their militaries for future conflicts. However, rushing to judgment about the efficacy of specific technologies in a protracted war that has no clear end in sight only impedes this learning process. Thus, prudent observers of modern war are right to question any technology being championed as a “war winner” until the war being used as an exemplar is won.

The late British historian, Sir Michael Howard, remarked in a 1973 lecture on Military Science in an Age of Peace, “that whatever doctrine the Armed Forces are working on now, they have got it wrong. I am also tempted to declare that it does not matter that they have got it wrong. What does matter is their capacity to get it right quickly when the moment arrives.”41

Hopefully, Sir Michael’s prescient words will stimulate continued sober analysis of the strengths and limitations of drones and AI on the modern battlefield. This will require some intellectual humility that we may all be wrong, including this author.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Col Greenwood is a Research Staff Member at the Institute for Defense Analyses. He was an Infantryman who commanded the 15th MEU (SOC), served as Director of the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, and completed multiple assign-ments in the Pentagon and on the National Security Council staff.

NOTES:

- Tomas Milasauskas and Livdvikas Jaskunas, “FPV Drones in Ukraine are Changing Mod-ern Warfare,” Atlantic Council, June 20, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrai-nealert/fpv-drones-in-ukraine-are-changing-modern-warfare.

- Kateryna Bondar, “How Ukraine’s Operation ‘Spider’s Web’ Redefines Asymmetric Warfare,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-ukraines-spider-web-operation-redefines-asymmetric-warfare.

- Roger Boyes, “Kyiv’s Drone Attack is a Pearl Harbor Moment,” The Times, June 3, 2025, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2025/06/02/ukraine-drone-strike-at-tack-russia-pearl-harbor/83987304007.

- Antonio Salinas and Jason P. Levay, “Military Revolutions from the Spanish Tercio to First-Person View Drones,” War on the Rocks, May 15, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/05/military-revolutions-from-the-spanish-tercio-to-first-person-view-drones.

- Margaret MacMillan, War: How Conflict Shaped Us (New York: Random House, 2020).

- Stacie Pettyjohn, “Evolution Not Revolution: Drone Warfare in Russia’s 2022 Invasion of Ukraine,” Center for a New American Security, February 2024, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep57900.

- Thomas C. Greenwood, “Why Ukraine’s Breakthrough Operations Are So Difficult,” The National Interest, December 31, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/why-ukraines-breakthrough-operations-are-so-difficult-207815; and J. Boone Bartholomees, “Theory of Victory,” Parameters 38, No. 2 (2008).

- Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Tactical Developments During the Third Year of the Russo-Ukraine War,” Royal United Services Institute, February 2025, https://www.rusi. org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/tactical-developments-during-third-year-russo-ukrainian-war.

- Andrew F. Krepinevich, “Calvary to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions,” The National Interest, No. 37 (1994).

- James R. Fitzsimonds and Jan M. Van Toll, “Revolution in Military Affairs,” Joint Forces Quarterly (Spring 1994).

- “Calvary to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions.”

- Stephen Biddle, Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

- Thomas G. Mahnken, Technology and the American Way of War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

- Amos Fox, “Drones Are Game-Changing, But They Are Not the Answer to the Inherent Challenges of Land Warfare,” Small Wars Journal, August 6, 2025, https://smallwarsjournal. com/2025/08/06/drones-are-game-changing.

- Jakub Jajcay, “I Fought in Ukraine and Here’s Why FPV Drones Kind of Suck,” War on the Rocks, June 26, 2025, https://warontherocks. com/2025/06/i-fought-in-ukraine-and-heres-why-fpv-drones-kind-of-suck.

- Andrew W. Marshall, “RMA Update,” Memorandum for the Record, Office of the Secretary of Defense (Washington, DC: May 1994).

- Williamson Murray, “Thinking About Revolutions in Military Affairs,” Joint Forces Quarterly (Summer 1997).

- Mark Cartright, “Blitzkrieg: The Lightning War Tactic of Combined Arms,” World History, November 28, 2024, https://www.worldhistory. org/Blitzkrieg.

- David R. Mets, The Long Search for a Surgical Strike: Precision Munitions and the Revolu-tion in Military Affairs (Montgomery:

Air University Press, October 2001). - Joseph Rogers, “What Operation Midnight Hammer Means for the Future of Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 23, 2025, https://www.csis. org/analysis/what-operation-midnight-hammer-means-future-irans-nuclear-ambitions.

- Ivo H. Daalder and Michael E. O’Hanlon, Winning Ugly: Nato’s War to Save Kosovo (Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, 2000).

- “Calvary to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions.”

- Charlie Goo, “American Dragon: This Missile Launcher Turns Tanks to Dust,” The National Interest, June 30, 2021, https://nation-alinterest.org/blog/reboot/american-dragon-missile-launcher-turns-tanks-dust-188853.

- John F. Keane and Stephen S. Carr, “A Brief History of Early Unmanned Aircraft,” Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab Technical Digest 32, No. 9 (2013).

- Tom Greenwood and Jim Greer, “Experimentation: The Road to Discovery,” Strategy Bridge, March 1, 2018, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/html/trecms/AD1223471/index.html.

- John D. Maurer, “The Future of Precision-Strike Warfare: Strategic Dynamics of Mature Military Revolutions,” Naval War College Re-view 76, No. 3 (2023).

- Alison Bath, “Navy Fired More than 200 Missiles to Fight Off Red Sea Shipping Attacks, Admiral Says,” Stars and Stripes, January 16, 2025, https://www.stripes.com/branches/navy/2025-01-16/houthis-navy-red-sea-missiles-drones-16500246.html.

- Thomas G. Mahnken, “Weapons: The Growth & Spread of the Precision-Strike Regime,” Daedalus 140, No. 3 (2011).

- “Weapons: The Growth & Spread of the Precision-Strike Regime.”

- Jason Shell, “How the IED Won: Dispelling the Myth of Tactical Success and Innovation,” War on the Rocks, May 1, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/05/how-the-ied-won-dispelling-the-myth-of-tactical-success-and-innovation.

- MSW, “The Cu Chi Tunnels,” WarHistory. Com, July 15, 2020, https://warhistory.org/@ msw/article/the-cu-chi-tunnels.

- Mick Ryan, “The New Adaptation War,” Substack.com, April 16, 2025, https://scsp222. substack.com/p/adaptation-war-with-mick-ryan.

- Kendrick Kuo, “How to Think About Risks in US Military Innovation,” Survival, February-March 2024, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2024.2309077.

- Kendrick Kuo, “Dangerous Changes: When Military Innovation Harms Combat Effectiveness,” International Security 47, No. 2 (2022);

- “How to Think About Risks in US Military Innovation.”

- “Dangerous Changes: When Military Innovation Harms Combat Effectiveness.”

- Lawrence Freedman, “Are Drones the Future of War?” Substack.com, July 29, 2025, https://samf.substack.com/p/are-drones-the-future-of-war.

- MacGregor Knox and Williamson Murray, The Dynamics of Military Revolution, (Cam-bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- Colin S. Gray, Weapons Don’t Make War: Policy, Strategy, and Military Technology (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993).

- Pat Garrett and Frank Hoffman, “Maneuver Warfare Is Not Dead, But It Must Evolve,” Proceedings, November 2023, https://www.usni. org/magazines/proceedings/2023/november/maneuver-warfare-not-dead-it-must-evolve.

- Michael Howard, “Military Science in the Age of Peace,” The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) Journal 119 (1974).