The Dogs of War: Canine Companions Vital to Corps’ Success

By: Chris KuhnsPosted on February 15, 2026

Executive Editor’s note: We bring you this story in recognition of Na-tion-al K9 Veterans Day on March 13. It marks the date in 1942 when the U.S. Army began training dogs specifically for military use.

A light, intermittent rain fell on Guam and the Marines of 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment on the night of July 25, 1944. The inky darkness was broken by occasional flares rocketing up from offshore destroyers and 60 mm mortars closer to the front lines. Along the entire line, Marines experienced probing attacks from the Japanese. The Marines of 1/9 could hear Japan’s night assault against their division’s reconnaissance company. Ahead of them lay the heights of Mount Tenjo, where the Japanese consumed sake, working themselves into a frenzy for an attack.

Embedded in the lines of Company C, an unusual trio of Marines huddled in a foxhole. Corporal Harry Brown and Private First Class Dale Fetzer slept fitfully. Perched on the lip was PFC Skipper, a black Labrador Retriever, ears perked up and listening for sounds undetectable to human senses. A canvas leash ran from Skipper’s collar to the hand of PFC Fetzer, his handler.

Around 4 a.m., Skipper abruptly shot up in a low crouch, staring toward Mount Tenjo. Every follicle of hair stood on end as Skipper bared his teeth and gave a nearly imperceptible growl. PFC Fetzer snapped awake, recognizing at once Skipper’s alert posture. Shaking his partner, Fetzer whispered, “Get the lieutenant. They are coming,” before turning his attention back to the dog. After quietly praising Skipper for his alert, he ordered him to the bottom of the hole, to lie down and stay.Around 4 a.m., Skipper abruptly shot up in a low crouch, staring toward Mount Tenjo. Every follicle of hair stood on end as Skipper bared his teeth and gave a nearly imperceptible growl. PFC Fetzer snapped awake, recognizing at once Skipper’s alert posture. Shaking his partner, Fetzer whispered, “Get the lieutenant. They are coming,” before turning his attention back to the dog. After quietly praising Skipper for his alert, he ordered him to the bottom of the hole, to lie down and stay.

Within 10 minutes, Japanese soldiers poured down from Mt. Tenjo, crashing into the lines of 1/9, attempting to exploit a gap between their regiment and 3rd Battalion, 21st Marine Regiment (3/21). Skipper lay nervously in the hole as the world erupted in gunfire. PFC Fetzer, atop the hole, fired away with his M1 carbine at the hordes of Japanese. A Japanese hand grenade shot into their foxhole, shredding Fetzer’s legs and sending him down into the hole, beside his lifeless comrade, Skipper. Fetzer later described what happened next as a blacked-out maniacal rage over the death of his dog. He leapt from his hole and, by his own account, killed every Japanese soldier he could find.

As sunlight swept away the horrors of that night, it revealed dead Japanese all around. Lieutenant William Putney, 3rd Marine War Dog Platoon (MWDP) Commander, found Fetzer sitting on the edge of his foxhole cradling Skipper’s body, tears streaming down his face. Lt Putney drove Fetzer and Skipper to graves registration, near Blue Beach, where they had landed five As sunlight swept away the horrors of that night, it revealed dead Japanese all around. Lieutenant William Putney, 3rd Marine War Dog Platoon (MWDP) Commander, found Fetzer sitting on the edge of his foxhole cradling Skipper’s body, tears streaming down his face. Lt Putney drove Fetzer and Skipper to graves registration, near Blue Beach, where they had landed five days earlier. The MWDP commanders had already established a war dog cemetery, beside 3rd Division’s. Skipper’s name was stenciled to a white cross, and he was laid to rest beside the Marines he had protected. Skipper was credited with saving the company with his early warning against the Japanese onslaught. He was not the first nor the last Marine war dog buried there.

The Inception of the War Dog

Using dogs in combat goes back centuries; however, the practice wasn’t adopted by the United States military prior to 1941. Working dogs were a foreign concept to the American people, particularly the military. When the events of Dec. 7, 1941, thrust America into World War II, the nation mobilized to assist the war effort. A civilian agency, Dogs for Defense, was created shortly after the outbreak of the war to recruit dogs for service with the military.

Initially, the Marine Corps turned down the idea of war dogs, believing only units directly involved in destroying the enemy or saving Marines should be created. But as weary Marines fought desperately for their lives on Guadalcanal, they came to understand the ferocity of the Japanese and the need for tactical advantages. The idea was reconsidered, perhaps influenced by the Marine Corps prewar publication “Small Wars Manual,” which stated that dogs “may sometimes be profitably employed … to detect the presence of hostile forces.” In November 1942, Commandant Thomas Holcomb ordered the establishment of a war dog training school at New River, N.C.

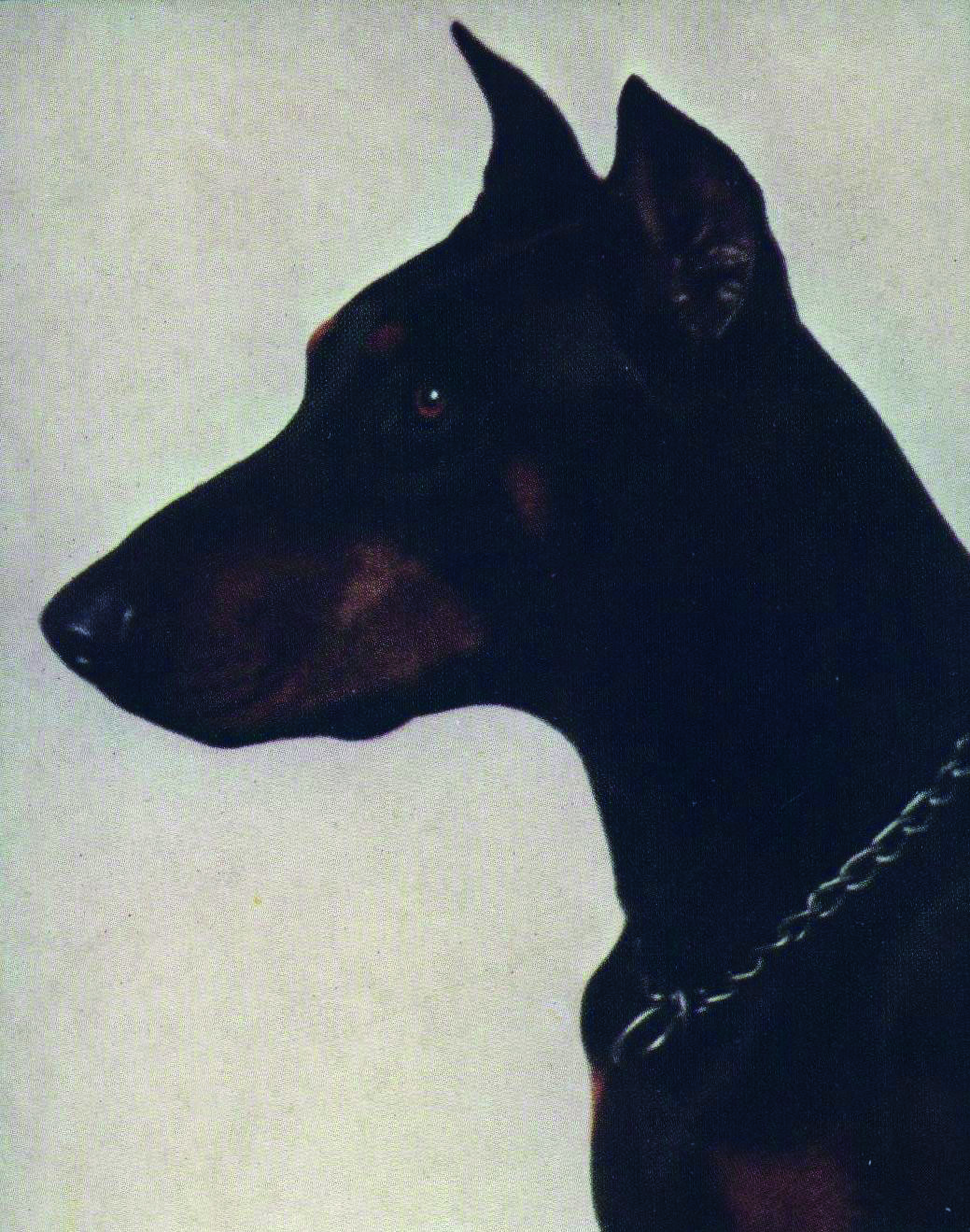

The first to arrive were 20 Marines and 38 dogs from Army training centers. More dogs came from the civilian population through donations made to the Marine Corps. The first donor was the Doberman Pinscher Club of America, which initially contributed 20 Dobermans. Recurring donations ensured Dobermans were included among all war dog platoons throughout the war. Families caught up in patriotic fervor donated their pets as well, leading to a mix of breeds in Marine kennels. There were few formal requirements for Marine dogs during the war.

Dogs were disqualified if they were too skittish, barked excessively or had a fear-based bite reflex. Dogs who passed the physical and temperament tests were paired with handlers, who came as infantrymen from the Fleet Marine Force or infantry training school. Once matched, they would then begin a 14-week course. Teams would be separated into one of three assigned jobs. Messenger dogs were trained to run back and forth between two handlers at the command “Report!” These dogs covered impressive distances and could track down a handler who was far out of eyesight.

Scout dogs were trained to lead patrols, never bark and sense for movement in their surrounding environment. Similarly, sentry dogs were trained to alert their handlers and guard command posts, stationary emplacements and the front line at night. Contrary to belief, dogs were never trained to “sniff” for the enemy. At the time hand-lers did not understand how to train a dog to alert based on scent. Instead, each dog was trained to detect movement, with their own unique way of alerting, which a handler had to learn and anticipate. A dog might crouch low and give a growl or point their nose at a movement. During training it was discovered that dogs can alert on enemy movement up to 500 yards away.

To the Pacific

Marines eyed up these “dog Marines” for the first time in 1942 and were skeptical of their abilities. The infantrymen imagined dogs barking at night, giving away their position or eating all their rations. No one wanted to give the 1st Marine War Dog Platoon a chance until the 2nd Raider Regiment commander, Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley, witnessed their capabilities.

On Nov. 1, 1943, D-day on Bougainville in the Northern Solomons, handlers climbed down cargo nets into Higgins boats while their dogs were lowered in improvised harnesses. They landed an hour after the first wave, splashing onto the thin strip of sand before plunging into the dark, impenetrable jungle. Two dog teams were attached to Company M, 3rd Raiders: Doberman scout dog Andy, with handlers PFCs Robert Lansley and John Mahoney, and German shepherd messenger dog Caesar, with handler PFC Rufus Mayo. Their task was to patrol down the Piva Trail and take up a blocking position deep in the enemy jungle. Andy led the way, giving multiple alerts on enemy positions, which the trailing Raiders deftly handled. Not a Marine was lost.

Despite the initial success, doom soon crept on the Raiders. Their radios became saturated with moisture as they fought off Japanese incursions on the trail. Caesar reestablished the communications link by running 1,500 yards nine times under fire, carrying handwritten messages. At sunrise on the morning of Nov. 3, PFC Mayo lay in a damp foxhole when Caesar suddenly leaped over the edge, teeth bared for a fight. Before Mayo could comprehend the situation, he recalled Caesar, who turned to run back. Just then, three shots rang out from the jungle. Caesar yelped and fled down the trail. Mayo took off after him and found Caesar back at the company area with another handler, three bullets in his body. Nearby Raiders, showing their newfound love for war dogs, improvised a litter and carried Caesar to the aid station for lifesaving surgery. He survived, returning only weeks later to duty and his adoring Raiders.

“An Unqualified Success”

Word spread across the Marine Corps, and the United States, about these four-legged heroes. Caesar’s likeness adorned postage stamps, and newspaper articles described the dog’s ordeal. LtCol Shapley praised the dogs’ performances, calling them “an unqualified success,” which encouraged additional war dog platoons. By the end of the war, seven war dog platoons were constituted. Each Marine division was assigned at least one war dog platoon. The dogs accompanied the infantry into every campaign from 1944 to the end of the war.

Although the infantrymen were dismissive at first, once the Marines dug in for the night, they watched and hoped for the war dogs and handlers to come to their lines for night security. These dogs, experts at catching infiltrators, remained alert all night. Riflemen discovered that if a dog and handler were in the hole with them, they could sleep, perhaps the only deep sleep they could get during a campaign. As the dog teams walked to the front lines in the evenings, they were welcomed with pre-dug foxholes and infantrymen inviting them in.

The war dogs led the riflemen into the jungles of Guam, flushed out Japanese stragglers on Saipan, endured the murderous shelling on Iwo Jima and shared the miserable conditions on Okinawa. During the Peleliu campaign, the war dogs shared astoundingly harsh conditions. Temperatures soared well into the triple digits, and razor-sharp coral, which covered the island, cut up the dogs’ paws. Handlers carried their dogs over the terrain to spare them the agony of walking.

PFC Thomas Price and his Doberman Chips, of the 5th MWDP, were attached to 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, on Peleliu. Price wrote home to his parents in October describing the torment of fighting there. Chips saved his life during the first night by alerting him to an infiltrator. He recounted his absolute terror as he waited, Ka-Bar in hand, for the enemy to come.

The next night, they endured a mortar barrage. “I got in a foxhole with Chips and started praying,” wrote Price. He continued, “Then Chips gave a yelp. I reached down and felt blood running down his leg.” Despite the wound, Chips alerted around 4 a.m. The entire company opened fire on this early morning attack, dispersing the Japanese before they could surprise the Marines. Both Chips and Price were wounded by shrapnel, and Chips was evacuated. He was one among dozens of war dog casualties during the brutal fight on Peleliu.

In another letter, Price wrote that “it would be like losing my right arm, if anything happened to Chips.” All handlers shared his sentiment, forming incredible bonds with their dogs. They endured all manners of hardship and terror, looking out for one another while enduring the most savage of conditions.

Even the dogs demonstrated these bonds of companionship. On Guam, the night of July 22, 1944, Edward Topka, 3rd MWDP, fought furiously for his life after his Doberman, Lucky, alerted. Topka was nearly overrun by Japanese but held them off at the cost of a mortal wound. Corpsmen found him at sunrise, surrounded by a dozen slain enemies. They did everything possible to save him. Lucky lay faithfully by Topka’s side. As Topka’s final breath left him, Lucky’s demeanor shifted from mournful to ferociously protective. He snapped at the corpsmen, driving them off Topka’s body. Teeth and claws bared, he stood watch over his fallen master, ready to tear apart anyone who came too close. It took several fellow handlers to subdue the devastated Lucky to recover Topka’s body. According to Lt Putney, Lucky was never the same, and he was sent back to the States.

Always Faithful

As the fighting on Okinawa died down in July 1945, the war dog platoons with the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions continued their patrols to uncover any bypassed Japanese. Marines in the Pacific were preparing to invade Japan when the news of the Japanese surrender reached them. Instead of invading, the men and dogs transitioned into an occupation force. Slowly, they were all sent back to Camp Lejeune, N.C., as the need for dogs decreased.

Originally, there was no plan for how to handle these aggressive, combat-hardened dogs. The idea of euthanasia was floated but instantly shut down by the platoon commanders who had endured combat alongside them. They developed a de-training program in the hopes of rehabilitating them.

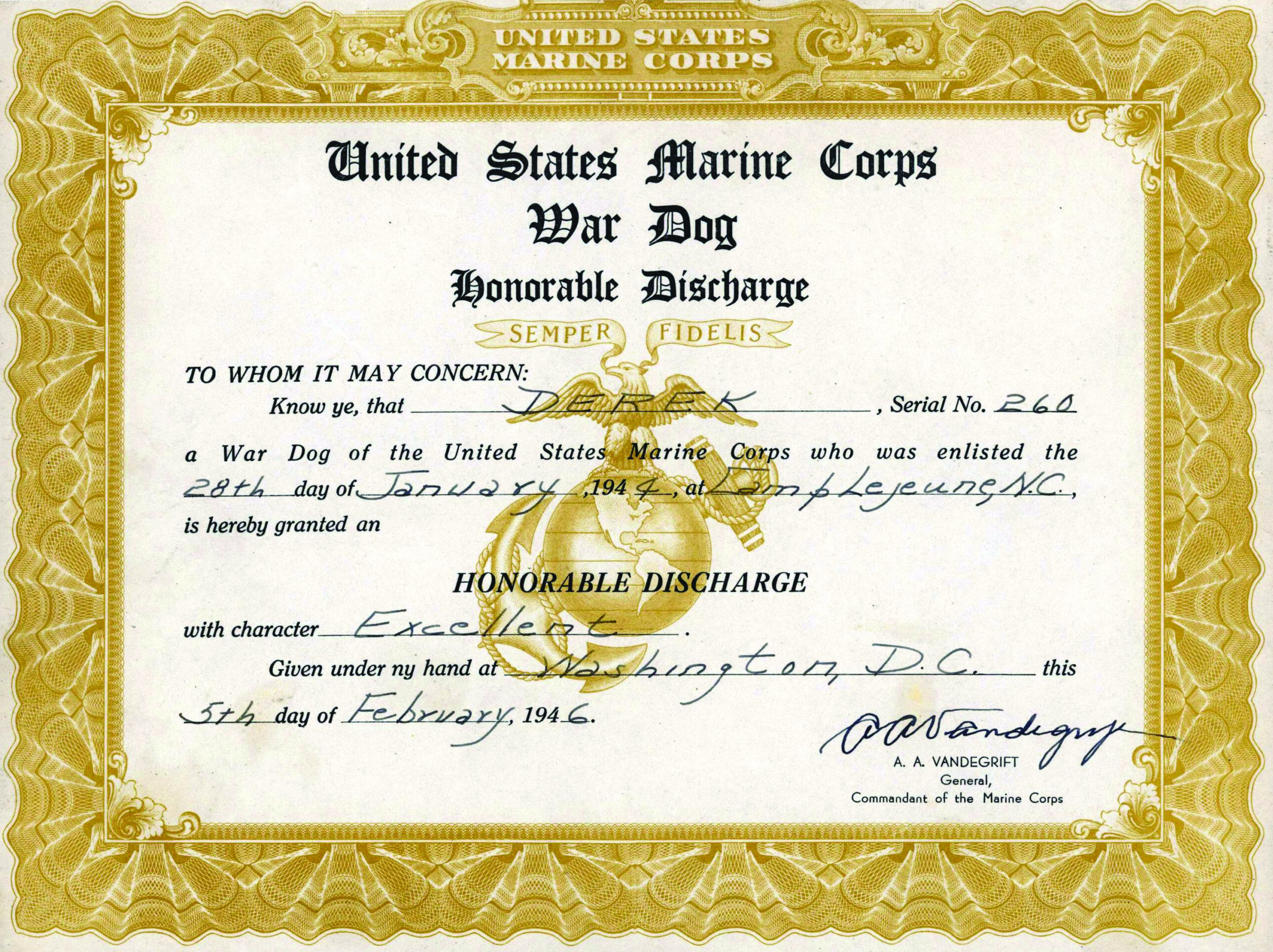

The dogs were trained to re-enter civilian life, breaking their military routine. Handlers were changed frequently, dogs were allowed to relax and Marines from the Camp Lejeune Women’s Reserve units took the dogs for walks. William Putney, now the war dog veterinarian at New River, tabulated that only four dogs, out of 559, were euthanized for extreme, trauma-related aggressiveness. This was an astounding accomplishment, contradictory to outside predictions.

When the war dog training facility shuttered in 1946, dogs were returned to their civilian owners. Many of the dogs were able to accompany their handlers, as Marines received permission from the original owners to keep their wartime companions. Tom Price and Chips went back to Maryland to continue their lives together. Few, like Corporal Marvin Corff and Rocky, from the 2nd MWDP, had to tearfully part ways. Corff’s last view of Rocky, his faithful companion through the war, was sitting on his owner’s front steps in Chicago, Ill.

The dogs and men of the Marine war dog platoons had followed the same motto as all Marines since the Corps’ inception: Semper Fidelis. These men and dogs endured the worst campaigns in the Pacific, never wavering in their dedication to mission and to each other. Their profound bond held them together, as it does all combat veterans. Their legacy of service lives on in memorials to these men and four-legged Marines across the country.

Nowhere is it more evident, however, than on a tiny corner of Guam, near a beach where decades earlier, Marines splashed ashore with their war dogs under fire. A statue of a Doberman overlooks the final resting place of the dogs who died during that campaign, including Skipper, the savior of Company C, 1/9. His ears are perked up, head erect, and he is vigilantly on watch, always faithful.

Featured Photo (Top): Pvt John L. Drugan and Pal, 4th MWDP, on Okinawa, May 1945. Pal saved a platoon of Marines from an ambush by alerting his handler of a hidden Japanese machine-gun nest.

About the Author

Chris Kuhns, a former Marine infantryman, separated from the Marine Corps to pursue his passion for military history, specializing in the history of the Marine Corps. He serves as the director of the Pennsylvania Military Museum in Boalsburg, Pa., and as the deputy director of the U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company, a nonprofit organization. He calls Gettysburg, Pa. home.

Enjoy this article?

Check out similar member exclusive articles on the MCA Archives:

Lucca: Wounded Marines War Dog Warms Hearts

Leatherneck

July 2013

By: Rebekka Heite

Forgotten No More: Remembered Forever

Leatherneck

October 2013

By: Nancy Hoffman

Smoke the Donkey: Marines Befriend “The Luckiest Donkey in Iraq”

Leatherneck

April 2016

By: Cate Folsom