A new application of Boyd’s model

The work of the late Col John Boyd has significantly influenced the doctrine and concepts of the U.S. armed forces for the last 30 years. Boyd’s achievements during his Air Force career include substantial contributions to fighter tactics and aircraft design.1 Yet, he is better known for his ever-evolving and eclectic theoretical efforts to define conflict and for his simple decision-making model, the famous “OODA loop.”2

In this article, we introduce another construct for consideration. The authors are avowed maneuverists, who find value in Col Boyd’s wide-ranging theories, notwithstanding his contempt for battles of attrition, which are sometimes unavoidable. Boyd’s detractors criticize the underlying historical cases he drew upon and his lack of published substantive scholarship. But over the last two generations, he has arguably offered better frameworks for thinking about warfare (especially at the tactical level) than anyone else. A concept that addresses uncertainty, cognition, moral factors, feedback loops, continuous adaptation, and time-competitive decision making is quite powerful. His theory rightly stresses the value of relative tempo vice just acting faster, which Boyd clearly understood.

Thus, we are not surprised that Boyd’s conception of war as a violent and time-competitive clash to disrupt an opponent’s mind and force cohesion has traction with many in the U.S. military and Marine warfighting doctrine.3 Boyd was respected and praised by numerous students of war.4 Additionally, having numerous devoted acolytes, the late strategic theorist and prolific author Colin Gray, counted Boyd as an honorable mention on his list of favorite strategic theorists.5 “The OODA loop may appear too humble to merit categorization as a grand theory,” Gray observed, “but that is what it is. It has an elegant simplicity, an extensive domain of applicability, and contains a high quality of insight about strategic essentials.”6 Scholars at the Army War College support this assessment.7

Boyd’s thinking also influenced the development of the U.S. Army’s AirLand Battle doctrine and underpins the Army’s concept of mission command, which embraces the delegation of responsibility and decision making down the chain of command to ensure tempo is not ceded to the enemy.8 The Navy’s Next Generation Air Dominance program, involving unmanned loyal wingmen flying with sixth-generation manned fighters, continues to assess the implications new technology will have on cockpit decision-making.9

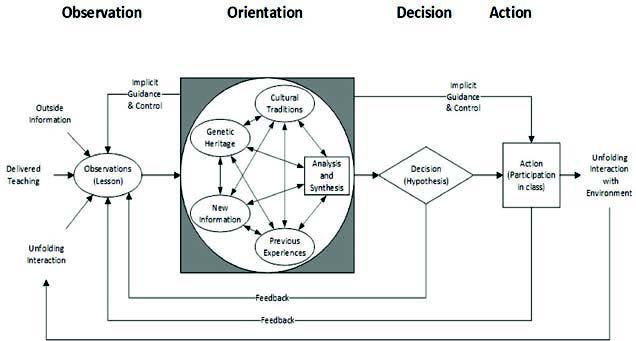

Moreover, Boyd’s OODA construct (see Figure 1) has been popularized in both military and management circles and has taken root in the military doctrine of many NATO countries.

But as previously noted, Boyd’s work is not without controversy or criticisms.10 Some scholars found the leap from Boyd’s cockpit experiences difficult to scale up to the operational and strategic levels of war.11 One critic labeled him a “blind strategist” who was “in the dark” due to his fraudulent reading of history.12 According to this critic, maneuver warfare somehow “corrupted the art of war” and is responsible for the catastrophic decisions made in Iraq and Afghanistan. That critique is both facile and hyperbolic. The most balanced observers of Boyd’s research acknowledge that he was not a professional historian and that his selection of historical cases reflected some bias.13

These shortcomings tempted some Army officers years ago to wishfully give the OODA loop a sendoff into academic oblivion.14 These authors focused on the simple four-step OODA loop, which is a shorthand description. They would be justified based on that abbreviated understanding. But they overlooked Boyd’s richer and expanded version that better depicts his thinking.15 There have been other efforts to construct alternative concepts including the critique–explore–compare–adapt loop and, in Australia, a pair of analysts proposed an act-sense-decide-adapt (ASDA) cycle.16 The ASDA concept stressed the competitive learning and adaptation aspects of warfare, as did Boyd.17

An Alternative Approach

Changes in the global security environment since the 1980s and ineluctable demands confronting today’s strategic planners suggest Boyd’s OODA loop could use a modest update. Thus, we propose a 4-D Model of discovery, design, decide, and disseminate/monitor. This builds upon Boyd’s OODA cycle while expanding his concept to enhance its relevance to the strategic level of war. Underpinning the need for the 4-D model are the following drivers:

- The deliberative nature of strategy is less about making fast decisions and more about identifying and deeply understanding the right problem and the rigorous generation of a sound solution.

- The collective character of strategy formulation, including group dynamics between commanders, allies, staffs, and specialists, and not just one individual’s cognitive cycle. The importance of discourse in building a shared understanding needs reinforcement.18

- The opportunity to incorporate advances in the cognitive sciences and other sciences that have occurred since Boyd developed his framework.19

- The thrust of the military design movement has steadily influenced strategic planning.20

- The need for a more explicit recognition of the role of risk in strategy formulation and implementation. There are new dimensions of strategic risk that transcend traditional concepts of risk to mission and forces that must now be accounted for: the risk that action or inaction poses to democratic governance, the global economy, and nation-states’ ability to marshal both manpower and materiel to meet the exigencies of protracted war.

In Boyd’s time, few fighter pilots or infantry commanders had to worry much about these factors. Today, they may find themselves quickly assigned to a combatant command headquarters and tasked with writing war plans and operations orders in an era of strategic competition and gray zone challenges. Thus, Boyd’s focus on operational or tactical success using the OODA cycle requires some translation for staff officers who are required to think strategically in peacetime but not yet moving to the sound of the guns.

The “4 D” Model (Discovery, Design, Decide, Disseminate/Monitor)

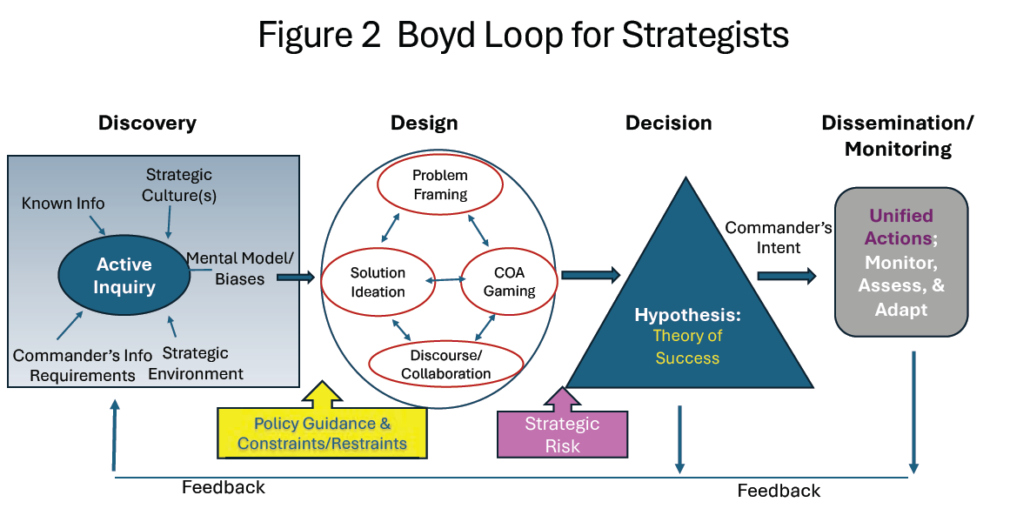

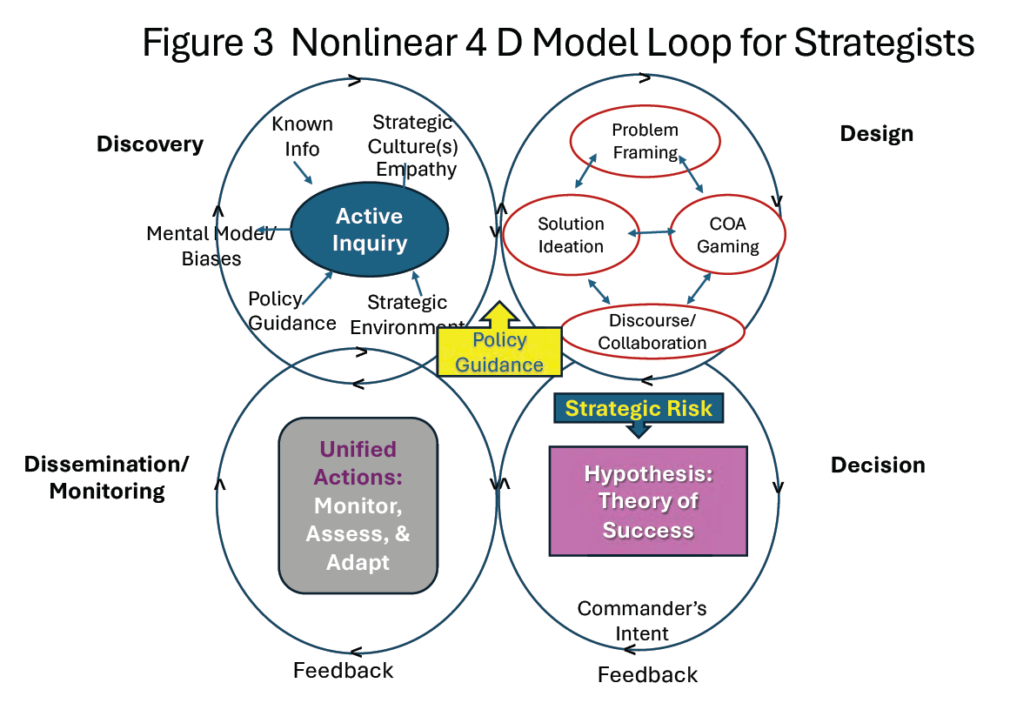

Our proposed model is presented in Figure 2. We came to recognize from Boyd that these are not isolated steps; instead, they are interconnected by information flows from continuous feedback loops.21 Our model blends Boyd’s interdisciplinary efforts with additional elements and attempts to help modern-day commanders and their staffs apply it to their critical command functions. To represent the nonlinear and continuous interaction that Boyd intended, we revised our version as depicted in Figure 3. This depiction came out of Boyd’s writing about the nonlinearity of warfare and seeks to better reflect the interactive nature of the various components.

Discovery

In place of observe, we propose discovery, which connotes a more active effort to learn and understand. Obviously, the Observe step is drawn from Boyd’s experience as a fighter pilot. Observing is not irrelevant to fighter pilots nor strategists, but a more proactive search is needed to build a comprehensive understanding of the strategic environment and the particular strategic culture of the adversary. What is necessary is an active effort to learn and appreciate what GEN McMaster called strategic empathy, which he defined as “the skill of understanding what drives and constrains one’s adversary.”22

In the discovery component, we include the identification and attempted resolution of “known unknowns” and an effort to satisfy the commander’s information requirements. We also include a recognition of the perspectives and mental modes, heuristics, and biases of key leaders and strategists, as Boyd properly noted.

An integral component of the discovery step involves identifying political constraints (actions that must be taken) and restraints (actions that are not authorized) that will shape the design step. In an era of great-power competition between nuclear-armed adversaries, escalation control and the political imperative to find acceptable off-ramps will impact the design of strategies involving the use of force between nuclear powers and their surrogates.

Design

In lieu of orientation, we have labeled the next step of the process as design. Whereas Boyd used orientation to capture the elements of sense-making, leading to analysis and synthesis, our model explicitly uses some of the simpler components of design as practiced in joint and Service planning methodologies. Design is not a single step; it is a developing awareness based on constantly changing circumstances and imperfect information. In Boyd’s briefing lectures, he stressed that orientation never ceases but rather constantly evolves as it takes in new data.23 “Orientation isn’t just a state you’re in,” he claimed, “it’s a process. You’re always orienting.”24 Likewise with design.

Some aspects of design theory have been incorporated within the existing joint planning process.25 While this has not been the sweeping paradigm change design advocates would like, it has helped generate the desired outcomes of the design movement (more creativity, critical thinking, challenging outdated frames, etc.). We agree with proponents who embrace complexity and novel ways to make sense of dynamic and non-linear environments and who want to exploit divergent thinking and leverage deep reflection.26

Yet, the notion of design theory and military applications is in flux. Now, as was the case a decade ago, there is little agreement on exactly what design thinking is or how to best apply it in strategy or operational art.27 The field is split between purists and pragmatists.28 While recognizing that design theory is a valuable but rather philosophical approach, we are practitioners who appreciate pragmatic applications.29 Design theory is not inconsistent with Boyd’s work, given his emphasis on complexity and systems theory, as well as the cognitive sciences.

Design is a useful intellectual approach that can assist planners who must grapple with wicked or ill-structured problems that are non-linear, interactively complex, and have no stopping rule or final end-state.30 But planners who ignore Boyd’s ideas and attempt to use design to overcome war’s inherent ambiguity and uncertainty will be gravely disappointed.31 At best, ill-structured problems can be managed or mitigated and not permanently solved. Instead of seeking some sort of utopian end state, planners must be content with achieving an acceptable sustainable state.32

Our conception of design includes problem framing, the first step in any serious strategy formulation process.33 That enables multiple diverse approaches (or courses of action) to be generated to resolve the gap between a perceived environment and a desired change. Design generates ideations in the form of potential solutions or mitigations, and these are fed into the analysis and synthesis process via the gaming of options or courses of action. All of this is interactively refined by discourse and collaboration among commanders and staffs. Critically, the insights gleaned from this process will almost always require the approaches or courses of action to be modified, necessitating yet another round of testing and experimentation before the Commander takes a decision.

Although doctrine still encourages strategists to develop a Theory of Victory, such verbiage can lead to over-reach when identifying the ends for which military force is going to be used. States acquire nuclear weapons to immunize themselves against regime change and existential defeat. Victory implies an outcome that is much more favorable than returning to the status quo ante or a negotiated settlement involving major concessions from both belligerents. History informs that the former is difficult to achieve and so a Theory of Success may have greater utility during strategy formulation.

Decision

The next component of the framework is the actual decision. Boyd appropriately labeled decisions as a hypothesis. This hypothesis represents a causal relationship between actions and desired ends, which is the operative theory of success in the evolving strategy.34

The commander is responsible and accountable for this decision as well as the degree of freedom of action for independent judgment that he or she delegates to subordinates and coalition members.35

In our model, we included strategic risk as an element in the decision component. Risk is an enduring reality in both strategic and operational decision making. The rigorous assessment of risk is or should be a critical and explicit step in strategy development. There is always a risk to any strategy thanks to the unrelenting reality of uncertainty in human affairs and especially war.36 Yet, it is often a weak link in U.S. strategy formulation and decision making.

Strategic risk is more than the risk to mission or force in joint risk analysis. It can come from many sources, both internal and external. Most of the time we look for risk from vulnerabilities or external events. The joint doctrine note on strategy suggests that risk analysis is an implicit function and relegates it to the assessment phase. It states, “Implicit to the implementation of a strategy is the identification of its associated costs and risks.”37 This is limiting and slightly problematic. Risk considerations should be explicit and start with the development of a strategy as well as execution and refinement from assessments. However, retired GEN Stan McChrystal insists that the greatest risk to our organization is from ourselves.38 Our lack of empathy, curiosity, and critical thinking leave us open to surprise from foreseeable hazards.

Risk assessment is a continuing process based on new information, or planning assumptions that reveal themselves to be inaccurate. A strategy and design team will look at risk in its gaming and synthesis. However, a conscious effort to accept risk or modify a strategy is the responsibility of the senior official approving the strategy. Risk is not well understood, and risk management is not applied consistently and explicitly at the policy and strategic decision-making levels. The U.S. strategy community needs to sharpen its appreciation for risk as a requisite step in testing strategic choices, making risk-informed decisions, and implementing strategy.

The inclusion of risk within the strategy process is now well recognized in U.S. doctrine but not by Boyd. Hence our inclusion of it as an explicit item to improve our capacity to appreciate risks to and from our strategy.39

Dissemination and Monitoring

After a decision has been made, it must be disseminated to all subordinate actors in such a way that captures the commander’s intent and logic. We have not used “act” since higher-level headquarters themselves do not act as much as support implementation and assessment.40 They do direct action across their formations, which must be continually assessed and which may generate the need to adapt the strategy or how it is being implemented. We specifically include monitor as a part of a commander’s function (and his staff) as it supports both mission command and documents the vital assessment process. Monitoring vice control is a notion we have absorbed from Boyd himself.41 Boyd felt that control was too focused on limiting freedom of action, which is the opposite of what learning and rapid adaptation are supposed to achieve.

Monitoring includes adopting useful assessment metrics that can help senior commanders and the civilian leaders they serve to answer the most difficult wartime question of all: is our strategy working? Bogus metrics and failing to ask this question frequently enough during a campaign can undermine the virtuous cycle of learning inherent to Boyd’s overall concept.

Regarding transitions and change, as the Russo-Ukraine war demonstrates, war is a competition in learning and adaptation.42 This is just as true at the strategy level as it is in the conduct of warfare.

Pitfalls

Strategists must be mindful of pitfalls that can lead to less-than-optimum outcomes or outright failure. We expect our adapted model will help ameliorate them. Richard Rumelt believes that “a good strategy recognizes the nature of the challenge and offers a way of surmounting it. Simply being ambitious is not a strategy.”43 Nor are big audacious goals and broad arrows on a map conducive to sound strategy. Some of the most dangerous pitfalls to remain aware of include:

Ignoring or Stifling Criticism

• The discovery step includes gathering as much relevant information about the problem as possible—the security environment, adversaries, friendly forces, allies, and partnered nations, and required resources to implement and sustain the strategy. A bias toward happy talk and good news can result in overly optimistic judgments that seep into the design step and lead to developing facile courses of action and the downplaying of associated risks. Prudent strategists are wary of too much sunshine intruding on the process and jealously guarding their objectivity and dispassionate analysis.

Forgotten Assumptions

• Strategy making takes time. Edward Miller has noted that “strategists are not clairvoyants,” and the development of War Plan Orange for defeating Imperial Japan in World War II was “a plan nurtured over thirty-five years.”44 Admittedly, this is a long time. Nevertheless, regardless of duration, strategy development requires that planners keep track of the assumptions underpinning their thinking and constantly cross-check them against reality. Circumstances will dictate whether old assumptions should be refined or discarded, and new ones adopted. A seemingly simple assumption like “country X or Y will or will not provide U.S. forces basing access,” can have an outsized impact on strategic outcomes. It is the impact that discarded, or newly adopted assumptions, have on the overall strategy—and the imperative to understand their second and third-order effects—that matters most.

Interagency Cooperation

• A strategy that integrates all elements of national power will, by necessity, involve multiple Executive Branch departments and agencies—each with its own unique organizational cultures and resource limitations. Understanding the role civilian agencies have in the strategy, and their timelines for execution, which, in most cases, differs from when the positive effects of their actions will be realized (i.e., financial sanctions and tariffs imposed, mobilization of industrial base, etc.) is crucial. Involving the interagency at the outset of the 4-D process will help promote a realistic understanding of what these stakeholders are bringing to the table, or not.

Rigid Adherence to the Plan

• Good strategies have some organic flexibility baked into their design so they can adapt to changing circumstances during implementation. Strategy refinements and modifications are almost always necessary to meet the moves and countermoves of a thinking adversary. The U.S. “Europe First” strategy during World War II allowed for operations in the Pacific and Mediterranean without causing decision makers to lose sight of the ultimate prize. Throughout the war, military objectives were expediently modified to exploit success and more effectively align resources with changing operational and strategic priorities. There is a reciprocal relationship between policy and strategy during war that should occur naturally.45 Identifying the shifts and the strategic trade-offs that should be made and for what reasons is strategic acumen of the highest order.

Conclusion

Like Clausewitz, Boyd deserves his place in the pantheon of useful philosophers of war. Oddly, both never really finished their work, and we are left with some questions to resolve on our own. We are not surprised Boyd’s various concepts resonate with many theorists and practitioners exposed to warfare. Despite the critics, we believe that any conception of warfare remains on solid ground with Boyd’s ideas about relative tempo, uncertainty, decision making, and adaptation. The convergence between Boyd and the Marine Corps is tied to their common emphasis on adapting to new circumstances in conflict. Ian Brown stresses, “such adaptability required a mind-set that could recognize when circumstances changed,” and the ability to “process the new information, and make those decisions necessary to adapt and triumph.”46 As noted earlier, the Army and the Navy also see some virtue in many of Boyd’s ideas.

We do not contend we have discovered the Rosetta Stone, but we offer this alternative model to help further leverage Boyd’s construct, especially for higher staff levels. We argue that Boyd would be happy to debate about the modified loop we have developed. Boyd hated dogmas and expected his ideas to germinate and evolve. Locking into a single mental model was tantamount to failure, or as Boyd colorfully put it, “You’ll get your pants pulled down.”47 His key point was to not become predictable or locked into templates which he labelled as cognitive stagnation.

While some of Boyd’s ideas can and should be challenged, his thinking “has shifted strategists, planners, and operators from mass-based to tempo- and disruption-based conceptions of war, conflict, and competition.”48 We should continue to build on that at all levels of war. The extensive use of the OODA loop model for decision making is a testament to the pervasive utility of this concept. Yet, Boyd’s contributions go well beyond the OODA framework and are worthy of serious study. However, they do not represent the final word. In fact, it is quite likely that the late Col Boyd would be unhappy if his provocative insights did not engender more debate and evolution.

>Col Greenwood (Ret) currently works as a Research Staff Member at the Institute for Defense Analyses in Alexandria, VA.

>>LtCol Hoffman (Ret) was, until his retirement, a Distinguished Research Fellow at the National Defense University, Washington, D.C.

Notes

1. Barry Watts and Mie Augier, “John Boyd

on Competition and Conflict,” Comparative Strategy 41, No. 3 (2022).

2. Which for those not familiar with the construct stands for observe, orient, decide, and act.

3. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCDP 1, Warfighting, (Washington, DC, 1997).

4. For positive assessments of Boyd’s many contributions see Grant T. Hammond, The Mind of War: John Boyd and American Security (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 2001); Chet Richards, Certain to Win, (Bloomington: Xlibris 2004); Robert Coram, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War (New York: Little, Brown, 2005); Ian T. Brown, A New Conception of War: John Boyd, the U.S. Marines, and Maneuver Warfare (Quantico: Marine Corps University Press, 2018).

5. Colin S. Gray, Modern Strategy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

6. Ibid.

7. Clay Chun and Jacqueline Whitt, “John Boyd and the “OODA Loop,” War Room blog, Army War College, January 8, 2019, https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/podcasts/boyd-ooda-loop-great-strategists.

8. Jamie L. Holm, An Alternate Portrait of Ruin: The Impact of John Boyd on United States Army Doctrine, (Fort Leavenworth: School of Advanced Military Studies, U.S. Command and General Staff College, 2021.)

9. John Robert Pellegrin, “Boyd in the Age of Loyal Wingmen,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, June 2024, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2024/june/boyd-age-loyal-wingmen.

10. Robert Polk, “A Critique of the Boyd Theory—Is It Relevant to the Army?” Defense Analysis 16, No. 3 (2000); and James Lane, “A Critique of John Boyd’s A Discourse on Winning and Losing,” Research Gate, February 2023, unpublished thesis, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368470051

_A_Critique_of_John_Boyd%27s_A_Discourse_on_Winning_and_Losing.

11. James Hasik, “Beyond the Briefing: Theoretical and Practical Problems in the Works and Legacy of John Boyd,” Contemporary Security Policy 34, No. 3 (2013).

12. Stephen Robinson, The Blind Strategist: John Boyd and the American Way of War (Dunedin: Exile Publishing, 2021).

13. Frans Osinga, “Getting a Discourse on Winning and Losing” A Primer on Boyd’s ‘Theory of Intellectual Evolution,’ Contemporary Security Policy 34, No. 3 (2013).

14. Kevin Benson and Steven Rotkoff, “Goodbye OODA Loop,” Armed Forces Journal, October 2011, http://armedforcesjournal.com/2011/10/6777464.

15. David Lyle, “Looped Back In,” Armed Forces Journal, December 2011, http://armedforcesjournal.com/perspectives-looped-back-in.

16. David J. Bryant, “Rethinking OODA: Toward a Modern Cognitive Framework of Command Decision Making,” Military Psychology 18, No. 3 (2009).

17. Justin Kelly and Mike Brennan, “OODA Versus ASDA: Metaphors at War,” Australian Army Journal 6, No. 3 (2009).

18. T.C. Greenwood and T.X. Hammes, “War Planning for Wicked Problems,” Armed Forces Journal, December 1, 2009, http://armedforcesjournal.com/war-planning-for-wicked-problems. See also Ben Zweibelson, “Seven Design Theory Considerations, An Approach to Ill-Structured Problems,” Military Review (November–December 2012).

19. Frans P.B. Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Thinking of John Boyd (New York: Routledge, 2006).

20. Ben Zweibeleson, Understanding the Military Design Movement: War, Change and Innovation (Abingdon: Routledge 2023).

21. Alistair Luft, “The OODA Loop and the Half-Beat,” Strategy Bridge, March 17, 2020, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/3/17/the-ooda-loop-and-the-half-beat.

22. H.R. McMaster, Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World (New York: Harper, 2020); H.R. McMaster, “Developing Strategic Empathy: History as the Foundation of Foreign Policy and National Security Strategy,” Journal of Military History 84 (2020); Allison Abbe, “Understanding the Adversary: Strategic Empathy and Perspective Taking in National Security,” Parameters 53, No. 2 (2023); and Montgomery McFate, “The Military Utility of Understanding Adversary Culture,” Joint Force Quarterly 38, No. 3 (2005).

23. “The OODA Loop and the Half-Beat.”

24. John Boyd, cited in Brett and Kate McKay, “The Tao of Boyd, How to Master the OODA Loop,” Unruh Turner Burke & Frees, September 15, 2014, https://www.paestateplanners.com/library/Tao-of-Boyd-article-2016.pdf.

25. Daniel E. Rauch and Matthew Tackett, “Design Thinking,” Joint Force Quarterly 101, No. 2 (2021). See also the Army Design Methodology and Marine Corps Planning Process.

26. Ben Zweibelson, “Fostering Deep Insight Through Substantive Play,” in Aaron P. Jackson ed., Design Thinking Applications for the Australian Defence Force, Joint Studies Paper Series No. 3 (Canberra: Center for Strategic Research, 2019).

27. Aaron Jackson, “Design Thinking: Applications for the Australian Defence Force,” in Aaron P. Jackson, ed., Design Thinking: Applications for the Australian Defence Force (Canberra: Australian Defence Publishing Service, 2019).

28. Aaron P. Jackson “A Tale of Two Designs: Developing the Australian Defence Force’s Latest Iteration of its Joint Operations Planning Doctrine,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17, No. 4 (2017).

29. Ben Zweibelson, “An Awkward Tango: Pairing Traditional Military Planning to Design and Why it Currently Fails to Work,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 16, No. 1 (2015).

30. “War Planning for Wicked Problems.”

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Andrew Carr, “Strategy as Problem Solving,” Parameters 54, No. 1 (2024).

34. On Theory of Success see Jeffrey W. Meiser, “Ends+Ways+Means=(Bad) Strategy,” Parameters 46, No. 4 (2016); Frank G. Hoffman, “The Missing Element in Crafting National Strategy, Theory of Success,” Joint Force Quarterly 97, No. 4 (2020); and Brad Roberts, On Theories of Victory: Red and Blue (Lawrence Livermore Laboratory: Center for Global Security Research, 2020).

35. Lawrence Freedman, Command, The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2022).

36. Colin S. Gray, Strategy and Defence Planning: Meeting the Challenge of Uncertainty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

37. U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Doctrine Note 2-19, Strategy, (Washington, DC: December 2019).

38. Stanley McChrystal and Anna Butrico, Risk: A User’s Guide (New York: Penguin, 2021).

39. A point stressed by a former Combatant Commander, see Kenneth F. McKenzie, Melting Point: High Command and War in the Twenty-first Century (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2024). See also Frank G. Hoffman, “A Weak Element in U.S. Strategy Formulation: Strategic Risk,” Joint Force Quarterly 116, No. 1 (2025).

40. Drawn from Jim Storr, Something Rotten, Land Command in the 21st Century (Havant: Howgate, 2022).

41. Boyd, slide 32 from “Organic Design for Command and Control,” May 1987.

42. Mick Ryan, “Russia’s Adaptation Advantage,” Foreign Affairs.com, February 5, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/russias-adaptation-advantage. For a deep study of adaptation in Ukraine see Mick Ryan, The War for Ukraine: Strategy and Adaptation Under Fire (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2024).

43. Richard P. Rumelt, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters (New York: Crown Business, 2011).

44. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991).

45. Dan Marston, “Limited War in the Nuclear Age: American Strategy in Korea,” in Hal Brands, ed., The New Makers of Modern Strategy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024).

46. A New Conception of War.

47. Boyd quoted in A New Conception of War.

48. Brian R. Price, “Decision Advantage and Initiative Completing Joint All-Domain Command and Control,” Air and Space Operations Review 3, No. 1 (2024).