2025 Gen Robert E. Hogaboom Leadership Writing Contest: First Place

Approachability is a bridge that connects you to your Marines. You are either paving the way, building barriers, or cutting off access. In the Marine Corps, trust and communication are paramount in candid conversations that can save lives and resources, making the difference between mission success or failure. The Marine Corps is a maneuver warfare organization that relies on trust built up and down the chain of command.1 Commanders owe their Marines clear intent and the resources to accomplish the mission. Followers owe their leaders accurate feedback, clarifying questions, and the trust to operate within the confines of the arena.

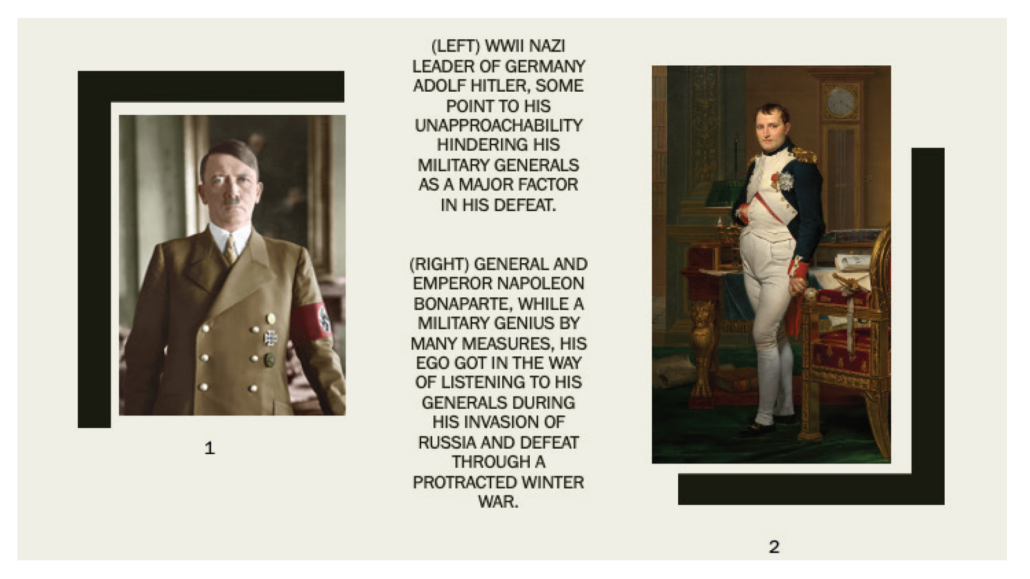

However, a culture of silence stifles creativity and hinders mission readiness. When senior leaders lack approachability, they struggle to gain a clear insight into what occurs at the lowest levels of their organizations. As leaders ascend through the ranks, their responsibilities expand, and their influence increases, yet their familiarity with the junior leaders and their troops decreases. An unintended consequence inflicted by overly busy schedules and competing priorities is a mounting difficulty for junior Marines to relate to their senior leaders. There is a direct correlation between increased rank and perceived harshness and limited interactions between senior and junior leaders often lead to the misperception that senior leaders are unrelatable and unapproachable.2 As leaders, assessing one’s level of approachability helps bridge the gap between senior leaders and junior Marines, leading to increased trust and effectiveness in the Marine Corps.

The Challenge of Relatability

The mask of command, like body armor on a deployment, does not have to be worn at all times and in all situations.3 At its core, the perception of approachability is amplified by military traditions of customs and courtesies and by increasingly busy schedules that leave minimal time for senior leaders to troop the lines. Senior leaders’ intent on maintaining their war face—a stoic and authoritative demeanor—may unintentionally reinforce the divide between leader and led.4 While maintaining this demeanor has a time and place, such as formal ceremonies or leading troops in combat operations, it can be counterproductive in day-to-day interactions. Knowing when, where, and with what level of formality shows a mature leader willing to adapt to their position and circumstances. Striking a balance when visiting Marines sends one of two messages: either you are never there and do not care, or you are there too much and do not trust them to operate without strict supervision.

Marines build trust through the process of “Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing,” especially while operating at the company level or below.5 Unfortunately, due to competing commitments, senior leaders do not have the freedom or time to be as involved with junior leaders during the trust-building process. Oftentimes, the context of decisions is lost while troops on the ground focus on the down and in of the tactical level, while senior leaders focus on the up and out at the operational and strategic levels. However, there must be a common ground in which information is shared from the bottom up and the top down to create a shared consciousness and culture. All levels of leadership should have ownership in this process; however, it is up to senior leaders to build a climate of approachability and trust that drives this process. It is the responsibility of leaders to link the purpose of tactical actions with strategic context while fostering unit morale and working to achieve common goals.

The Power of Approachability

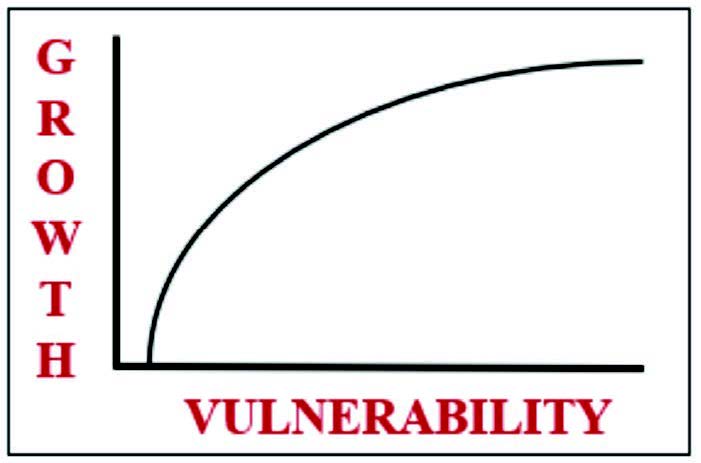

Being an approachable leader is not a sign of weakness; it is a powerful tool that enables senior leaders to gain the trust of their subordinates and access to the unvarnished truth. Approachable leaders foster an environment where junior Marines feel valued and empowered to speak openly, which helps to identify and address problems before they escalate. There are several ways a senior leader can display approachability and build two-way communication. Senior leaders can increase their approachability by being conscious of their demeanor and communication style, prioritizing face-to-face interactions, attending training, visiting deployed forces, and holding regularly scheduled town halls.

Leadership Tools for Approachability

Effective communication promotes a sense of purpose, trust, and collaboration that is essential for senior leaders when engaging with junior leaders. Senior leaders must ensure their messages resonate and inspire action by self-reflecting on, “Who is my audience? What’s the best method to reach them? How long do I have? What methods are available to me?”6 For junior Marines, effective communication must be clear, concise, and relatable to compete with their limited attention span, which is often divided among various work responsibilities and entertainment distractions. Communication must be tailored to reach your intended audiences while fostering trust and rapport. Additionally, feedback from trusted advisors and previous “gray beards” provides leaders with both wisdom and wasta.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps demonstrates effective communication by using social media platforms to communicate short, impactful video clips that deliver key messages such as reminders to complete the annual Combat Fitness Test.7 These videos, tailored to the Marine ethos, use straightforward language and relatable scenarios to connect with Marines at all levels, fostering trust, unity, and approachability. By leveraging modern technology and brevity, leaders ensure that critical guidance and values are shared effectively, empowering junior Marines to act decisively and confidently.

Demeanor plays a crucial role in shaping how others perceive us and directly influences our ability to build relationships. While it may seem minor, demeanor has significant leadership implications. A large portion of communication is non-verbal, meaning even small adjustments in bearing can greatly enhance approachability and effectiveness in leadership.8 Leaders who smile, engage in casual conversations, and show genuine interest in their Marines’ lives create a sense of camaraderie. A leader who smiles more appears relatable and less intimidating. This does not mean that leaders should forgo professionalism or adopt a perpetual grin, but rather, they should be mindful of how their expressions and body language impact their Marines’ perspectives. A sideways glance of displeasure during a brief can leave some Marines questioning their abilities and willingness to speak their minds.

In-person communication should be prioritized to ensure non-verbal body language is used to convey your meaning, especially when controversial or complex ideas need communicating. Senior leaders can cultivate approachability by prioritizing face-to-face interactions. Whenever possible, communication should be delivered in the most personable way possible, especially if it is sensitive or personal, such as the loss of a loved one or corrective action. Communication priority should start with face-to-face, followed by video, then voice calls, and lastly, written messages.9

Visible presence could include visiting the companies, walking the lines, eating meals with your Marines, casual meetings, planned mentorship sessions, and unit social events. During these interactions, leaders should practice active listening, demonstrate empathy, and refrain from passing immediate judgment. Senior leaders should leverage informal settings to foster candid conversations. These small actions signal that the senior leader is not just an authority figure but also a mentor and an ally.10 When Marines see their leaders as approachable, they are more likely to share their honest perspectives.

To learn what is happening on the ground requires being on the ground. By visiting in person, listening, and then sharing context for Marines wondering about policy or strategic changes that impact them, an approachable connection is much more likely. Often, a unit’s dynamics might go unnoticed without taking the time to visit the troops. Battlefield circulations can seem like an excuse to get out of the office or rack up frequent flyer miles, but the message it sends to the troops and the insights gained by observing and listening to Marines cannot be replicated by storyboards or situation reports. Battlefield circulations can provide an opportunity for a senior leader to be approachable, and they must be willing and able to provide context to things their Marines care about. All decisions are made in context. If someone does not understand the decision, they likely do not understand the context. Leaders who share context find their formations less resistant to change, and therefore, approachability is invaluable during times of innovation and change.

Senior leaders’ participation in mess nights, warrior nights, and the Marine Corps Ball might seem like trivial matters, but they provide Marines of all ranks and specialties an opportunity to commune and share in a setting that fosters relationship-building and transparent communication. By breaking down the barriers of rank and formality in these settings, leaders create an environment where ground truth can flourish as everyone takes part as a family of warriors. As trust increases, the speed of actions and decisions will also increase, creating a tempo Marines strive for in maneuver warfare.11

The last method is the inclusion of town hall meetings. A good method to assess the trust built between senior and junior leaders is the presence of challenging questions and two-way dialogue in public forums. If senior leaders are practicing the aforementioned approachability skills, town halls should provide insightful feedback. While approachability fosters open communication and trust, it also necessitates guiding interactions to remain productive and respectful, especially in public forums where poorly framed questions can undermine credibility, distract from the discussions, and hinder unit morale. By setting the tone for what constitutes thoughtful inquiry, leaders can encourage dialogue while maintaining professionalism.

Dumb Questions Exist, a Litmus Test: Arrogance, Ignorance, or Agenda

While senior leaders should take the mantle when developing approachability, junior leaders also hold responsibility for their demeanor and actions. For example, a senior leader should encourage open and candid dialogue, but that does not mean all questions are appropriate. Most Marines have heard questions that were not well thought out, in which the audience rolls their eyes and the chain of command grumbles under their breath. There is a three-part self-diagnosis everyone should ask before asking a question in a public forum:

One: Am I demonstrating arrogance? Everyone has met over-eager people who know the answer to the question but wish to grandstand while citing their litany of achievements and knowledge.

Two: Does this question show ignorance? Ignorance is measured within the context of the experience, rank, and length of service of the person asking the question. A junior Marine with limited experience has more room to ask foundational questions as opposed to someone who clearly should know the answer to what they are asking yet is demonstrating holes in their professional education out of laziness, immaturity, or low IQ.

Three: Does this question display an agenda? For example, when the Marine Corps controversially decided to divest of tanks, many tankers stood up in public settings with questions to senior leaders designed to point out their agenda to retrieve the steel beasts from the scrap heap of history.12

Junior Leader Responsibility—Moral Courage

Approachability for senior leaders has utility, however, that does not negate junior leaders from displaying moral courage in the case of unapproachable leaders. George C. Marshall offers a case study on courage in the face of unapproachability. As a junior officer, George C. Marshall demonstrated significant moral courage in the face of adversity. Marshall served on the staff of a historically unapproachable leader, GEN John “Blackjack” Pershing. Equivalent to a six-star general, Pershing was known for his blistering tirades and blunt demeanor.13 However, long before Marshall became the Chief of Staff of the Army, the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of State responsible for the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after World War II. He first stood up to his unapproachable leader with honesty and humility while deployed to France in World War I.14 Although initially taken aback, Pershing respected Marshall as a man he could trust to give the painful truth instead of the pleasing lie.

Conclusion

Approachability is a cornerstone of effective leadership, yet it is often overlooked as leaders climb the ranks. By smiling, engaging with Marines on a personal level, and fostering open communication, senior leaders can bridge the gap that separates them from their subordinates. This connection not only builds trust and morale but also provides access to the ground truth needed to make informed decisions. In a profession where lives depend on effective leadership, the importance of approachability cannot be overstated. Senior leaders must embrace this trait, recognizing that genuine connection with their Marines is the foundation of mission success.

>LtCol Mitchell is the Marine Raider Regiment Operations Officer. He began his Marine Corps career as an Infantry Officer before becoming a Marine Raider. He holds a master’s degree from Air Force University, specializing in Russian proxy warfare, and another from the Naval Postgraduate School, focusing on the Stand-In Force concept in Indo-Pacific conflict. Throughout his career, he has been deployed globally on a range of assignments.

Notes

1. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCDP 1, Warfighting, (Washington, DC: 1997).

2. Eric Wendt, “DA3900 Command & Leadership: Perceived Harshness and Positivity Model,” (lecture, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, October 10, 2023).

3. John Keegan, The Mask of Command (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1988).

4. Full Metal Jacket, directed by Stanley Kubrick (Warner Bros, 1987).

5. Admin, “What Is Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing?” Six Sigma Daily, August 17, 2020, https://www.sixsigmadaily.com/what-is-forming-storming-norming-performing.

6. David Grossman, “6 Steps for Effectively Connecting with Your Audience,” Your Thought Partner, July 18, 2022. https://www.yourthoughtpartner.com/blog/6-steps-for-effectively-connecting-with-your-audiences.

7. GEN Eric Smith, “Commandant of the @USMC (@CMC_MarineCorps)/X,” X, November 27, 2024, https://x.com/CMC_MarineCorps?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1861876810738483360%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Ftaskandpurpose.com%2Fculture%2Fmarine-cft-commandant-eric-smith%2F.

8. Chris Voss, “How to Use the 7-38-55 Rule to Negotiate Effectively,” MasterClass, June 7, 2021, https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-use-the-7-38-55-rule-to-negotiate-effectively.

9. Eric Wendt, “DA3900 Command & Leadership: Communication Hierarchy Model,” (lecture, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, October 10, 2023).

10. Director, Marine Corps Staff and Administration and Resource Management Division, HQMC Mentoring Guide, (Washington, DC: n.d.).

11. Stephen M.R. Covey and Rebecca R. Merrill, The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything (New York: Free Press, 2008).

12. Matt Gonzalez, “Force Design 2030: Divesting to Meet the Future Threat,” Marines.mil, December 1, 2021, https://www.marines.mil/News/News-Display/Article/2857680/force-design-2030-divesting-to-meet-the-future-threat.

13. Public Broadcasting Service, “Black Jack Pershing: Love and War,” PBS Learning Media. n.d., https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/collection/black-jack-pershing-love-and-war.

14. GEN George C. Marshall, “I’m Sorry, Mr. President, But I Don’t Agree With That At All,” The George C. Marshall Foundation, February 4, 2021, https://www.marshallfoundation.org/articles-and-features/im-sorry-mr-president-but-i-dont-agree-with-that-at-all.