How LAR Wins in the Deep Fight

2025 LtCol Earl “Pete” Ellis Essay Contest: Second Place

On an early morning outside Jõhvi, Estonia, a Marine Corps light armored reconnaissance (LAR) company occupies a screen along a narrow corridor of farmland interspersed with pine forest. One hundred kilometers to the southwest, a MEU and a NATO battlegroup stage to seize key terrain across the Baltic. Bound to the road network due to heavy forest, the company pushes its eight-wheeled, 25mm armed light armored vehicles (LAV-25) forward, establishing observation posts and seeking to gain and maintain contact with the advance guard of an approaching enemy battalion tactical group. Mounted in vehicles designed in the 70s and fielded in the 1980s, the company’s mission is straightforward but unforgiving: provide early warning of enemy activity and provide decision space for higher-echelon commanders.

Within minutes, the company is in contact. Overhead, small drones loiter freely, marking positions for enemy artillery and dropping shaped charges onto the static and exposed LAVs. First-person-view (FPV) quadcopters slip under the dense canopy, striking the vehicles concealed in hasty hide sites. Enemy infiltration teams mounted on civilian all-terrain vehicles probe the screen line, dismounting to bypass the company’s fixed observation posts to sniff out routes for exploitation. What began as a classic security mission for which LAR has trained for 40 years, unspools into a disaggregated unmanned aerial system (UAS) and sensor fight for which the Marines are ill-equipped. As the fight deteriorates, radio nets clog with reports of enemy precision fires, mobility kills, and rapid attrition. The company evaporated faster than any retrograde or recovery plan could absorb.

As the firefight built ashore, unmarked commercial watercraft, part of a “shadow fleet” operating under layered ambiguity, sailed the coastal traffic patterns north of Jõhvi.1 Exploiting flags-of-convenience paperwork, Automatic Identification System gaps, and routine harbor clutter, a 30-person raid force disembarks, quickly moving inland along forest tracks to harass the main NATO supply routes. Using low-power radios, commercial quadcopters, and cached munitions, the infiltration team stages hasty ambushes, lays counter-mobility obstacles, and cues indirect fire from standoff positions. Their aim is tempo vice destruction: delay, disrupt, seed doubt. In under two hours, the LAR company is combat ineffective. Friendly vehicles are fixed, the MEU’s screen penetrated, and LAR is violently pulled into a reality its design and doctrine were never built to endure.

What happened outside Jõhvi was not just a tactical failure—it was a systems failure. It exposed the growing gap between legacy platforms and modern threats, between the doctrine we have and the fight that is already here. Additionally, it also clarified the path forward. This article proposes a restructured four-platoon LAR company: two security platoons, a reconnaissance platoon, and a fusion platoon. This practical and immediate concept bridges the gap to evolve the LAR force from a platform-bound screen line into a modern sensor-enabled, reconnaissance-integrated network. By leveraging fieldable technology and rethinking organizational structure at the company level, this model provides MAGTFs with a scalable advantage: sensing earlier, making decisions faster, and imposing costs across domains and environments. This evolution of LAR is more than a one-off fix; it reflects a broader challenge across the Marine Corps: how to adapt legacy systems and structures to meet the demands of a rapidly changing fight without waiting for the perfect solution.

The Challenge

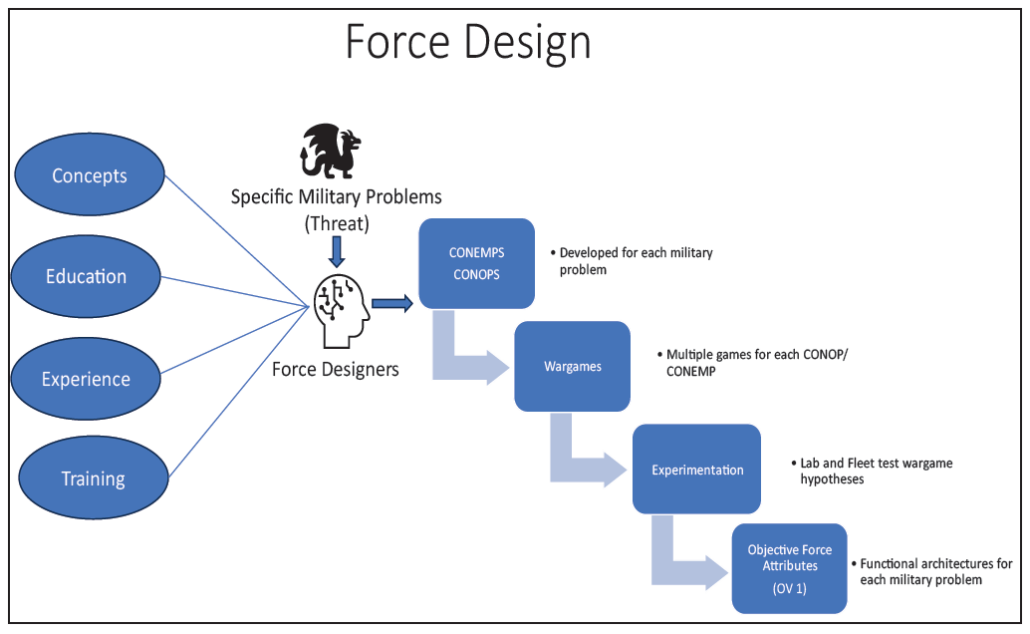

The issue facing the Corps’ LAR community is not direction; it is velocity. The ongoing transformation within the LAR community mirrors the larger shift across the Marine Corps. Central themes include disciplined experimentation under Force Design: aggressive use of accessible, often commercial off-the-shelf technology; preparation for new vehicles and tools; and the development of concepts of employment that meet today’s tasks while anticipating tomorrow’s fight. Force Design’s message to the LAR community is unambiguous: transition from platform-centric LAR to all-domain mobile reconnaissance inside the emerging mobile reconnaissance battalion—integrating land, maritime, and unmanned reconnaissance to link sensors to shooters and build joint/combined kill webs in contested littorals.2 This shift pushes LAR into the multi-domain fight while demanding we fully embrace new ways of sensing and communicating. These shifts enable us to generate aimpoints and close kill chains without friction and redundant reachback. Layered over this is a familiar strain of insecurity about identity and purpose, an unease that has long shaped debates inside the Corps, which some (half-jokingly) call the “platypus syndrome.” Change is assumed; tempo is the test; LAR must evolve fast enough to preserve core advantages while integrating pervasive digital capability.

Much good work is already on the table, but more must be done in the near term. LtCol John Dick and 3d LAR demonstrated the value of a bottom-up approach: building organic FPV strike teams inside the ground com-bat element, training to a repeatable cue-confirm-strike drill, treating power, electromagnetic action, and airspace as fire-support problems, and deliberately using commercial tools to balance cost, sustainment, and risk.3 Maj Brent Jurmu, Maj Brandon Klewicki, and LtCol Matthew Tweedy emphasize the structural need for change: move now toward the mobile reconnaissance battalion, prioritize sensing over platform identity, organize for teaming between manned and unmanned systems, open-architecture command and control to enable any sensor to feed any shooter, and resource resilient communications, power, and logistics as combat enablers rather than afterthoughts.4 Retired Col Philip Laing’s earlier thesis reinforces this by asserting that LAR is a mind-set, not a hull. The focus must be on reconnaissance pull, tempo, deception, dispersion, and mounted—dismounted integration—while warning against let-ting the vehicle define the unit.5

What these contributions do not fully solve is the immediate bridge between what LAR and the MAGTF currently retain and what we need next. We require a tactical force construct that operates with legacy LAVs and available light vehicles yet delivers stand-in sensing and fast sensor-to-shooter handoffs. This includes a practical gear list, training progression, and command-and-control habits that work tomorrow morning, not just in the out-years. Additionally, we must prioritize survivability, particularly armor survivability, ensuring that our vehicles can withstand emerging threats while maintaining operational flexibility. That is the bridging solution.

The Bridging Solution

What follows is a concept of employment and equipment, validated by Apache Company’s role within 2d LAR’s Task Force Destroyer during our Baltic deployment in the summer of 2025. The concept preserves LAR’s core reconnaissance and security functions while providing a practical framework to integrate enhanced sensing, fusion, and shaping capabilities expected of next-generation formations. Drawing on recent conflicts and years of community experimentation, the design postures usable capabilities now with the equipment on hand while providing on-ramps for the force to swell additional kit to expand our force offering. The result is a highly mobile, flexible formation that leverages existing assets and tactics, creates clear on-ramps for accelerated fielding of new sensors and systems, and reduces operational risk while preserving maneuver and survivability. The design works at the company level for MEU and MAGTF requirements and scales to a three-line company battalion construct. Finally, this sensor-laden formation travels well. It nests naturally within the Joint Force and exploits the Marine Corps’ inherent strength, our expeditionary character.

How Apache 2d LAR Fights

Apache Company was organized around three complementary platoon constructs that executed concurrent reconnaissance and security. The company can cover a 20 km² land area of operations and sense more than 30 miles off the coast. In effect, Apache fielded a multi-domain, long-range sensor company and stood up company-level command, control, communications, and computing with mostly on-hand equipment. The company was reinforced by 2d LAR’s intelligence section, Marine Forces Europe and Africa, II MEF 2d MarDiv enablers, and a few proactive contract partners. This concept has been greatly influenced by the vision outlined by Dr. Jack Watling in his book Arms of the Future.6

Reconnaissance Platoon

Built on ultra-light vehicles and operating near/on the contact line, the platoon carried long-range communications, Group-1 sUAS, multi-domain sensors, and medium direct-fire weapons (machineguns and recoilless rifles). Small in signature and highly mobile, it served as the company’s contact element—confirming or denying information requirements from higher and contributing new information to feed the intelligence cycle through timely ground reporting to the fusion platoon. It executed rapid ambushes to harass, disrupt, and buy time in restrictive terrain. By trading armor for speed, the platoon consistently punched above its weight.

Security Platoon

Positioned in depth behind the reconnaissance platoon, the security platoon operated LAV-25 and anti-tank variants. It preserved the company’s freedom of maneuver by providing armored overwatch and reinforcement for the reconnaissance platoon. From a relative standoff, it employed stabilized, long-duration sensors and Group-1 sUAS to detect and track enemy axes of advance. This posture enabled us to orient killing systems without becoming decisively engaged. As the company’s backstop, it delivered the armored punch to interdict maneuver, absorb pressure, and maintain tempo.

Fusion Platoon

Operating from a suite of LAVs tailored to specific mission requirements and a small complement of utility task vehicles (UTV) for last-mile mobility and logistics, the platoon provided Group-2 sUAS, mesh communications to tie into higher headquarters, a light surveillance and reconnaissance coordination center package, and expeditionary sustainment and maintenance inherent to any LAR formation. It was also where, as Apache dubbed it, a “Reconnaissance Integration Network” was exercised: information drove decisions, and mission command stayed forward. The fusion platoon pulled feeds from the furthest-forward sensors and pushed critical data across the battalion network, working in near real time with the S-2 to turn raw detections into targetable tracks. With our company dispersed to provide significant “depth by default,” our maritime domain awareness team employed sensors, meshed with partner-nation feeds, and flew group-2 sUAS over the littorals. Fusion packaged and distributed; battalion prioritized and matched effects. The result was a rapid targeting rhythm by which reconnaissance, security, fusion, and the S-2 moved as one system.

We did uncover a few key gaps, however, in lethality and sustainment. To supercharge the next iteration, the company must leverage the full potential of our force by enhancing both capability and reach. First, field command-launch units to amplify our armored killing power, enabling faster, more agile responses to emerging threats. Expand UTV capacity for increased power generation and cargo carry, allowing for sustained operations in austere environments. Integrate additional sensors to broaden our sUAS screen and strengthen the fusion network, improving situational awareness and intelligence flow across units. Bring in the next wave of sUAS and counter-UAS tools to stay ahead of evolving threats in the air. Finally, provide access to, and training for, modernized data-driven targeting software that seamlessly connects company-level targeting with MAGTF and joint fires, ensuring precise and synchronized engagements. These enhancements would not only elevate LAR’s operational capabilities but also ensure it is an even more effective and indispensable asset to the broader mission, increasing efficiency, accuracy, and the ability to project power across the deep battlespace.

Advantage

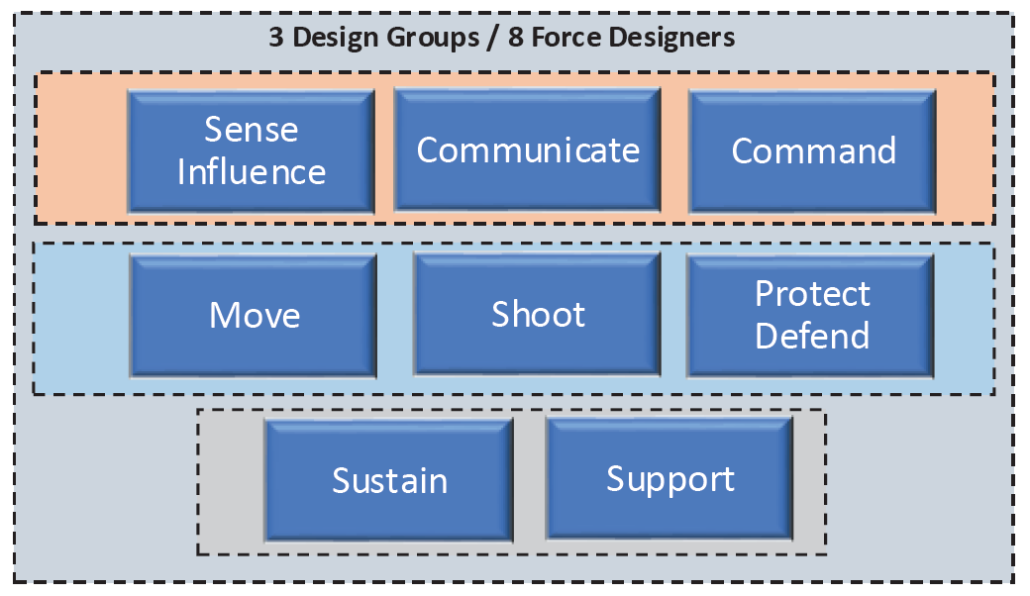

Together, these three elements produced a survivable, organically supported company that sensed, decided, and acted at the tempo the deep fight demands; feeding higher headquarters while shaping the fight in front of it. Following the Baltic deployment, Apache stood up a second security platoon, establishing one reconnaissance platoon, two security platoons, and a fusion platoon, for a total of 31 vehicles: 20 LAVs and 11 UTVs.

This concept of employment shows how LAR can evolve from a legacy cavalry formation into a modern stand-in sensor ecosystem. It retains traditional reconnaissance and security capabilities while posturing to absorb new technology as it arrives. Light reconnaissance brings agile, low-signature sensing and harassment. Armored security preserves freedom of maneuver, provides lift and power, and delivers the kinetic punch. Fusion, as the sensor and sustainment hub, closes the sensor-to-shooter chain and keeps the company supplied and computing forward.

The outcome is a formation that can operate independently for ten to fourteen days, answer commanders’ priority information requirements in stride, and sustain operations across littoral terrain while contributing to the broader kill web. It aligns with past experimentation proposals while refocusing on the enduring tasks of reconnaissance and security. This modern formation turns today’s kit into near-term advantage.

The Counter

At the tactical edge, legacy hulls with bolt-on tech are delicate. Power and computing are often the first to fail; when they do, the “sprint” stops. Edge-level processing, exploitation and dissemination and target formatting can compress time but widen risk: deconfliction with close air support; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; long-range fires on a tight MSR turns into information overload, and one bad grid buys fratricide. A LAV used as a node is still a hot, loud, tall target, often easier to find than to fuel. Adding maritime domain awareness to land feeds risks data overload and slower decisions, and roles blur: infantry battalions already field scouts and recon battalion owns the deep fight. Where does an LAR stand-in sensor company end and its missions begin?

This construct is built to fight through the loss of fragile links, with Group-1/2 feeds treated as temporary: valuable when up, replaceable when not. We layer sensors and plan graceful degradation, reverting to traditional methods if the network fails. First-person-view provides precision fires, task-organized and rationed by target value, with conventional fires as backup. Edge-level processing, exploitation, and dissemination safeguards ensure target packets follow rules of engagement, grid-quality checks, and restricted-operating-zone discipline to prevent fratricide. Light armored vehicles as nodes operate from defilade, acting as generators and routers before becoming targets. Endurance is key, supported by low-mobility screens, low signature-long duration observation, and pre-staged supplies. Light-armored reconnaissance is self-sustained, with maintenance, recovery, power, and logistics under armor that outranges infantry battalions. Maritime domain awareness is just another sensor lane, with priority information requirements and named areas of interest feeding into a fusion platoon, which in turn generates tracks and releasable aimpoints for higher echelons. Light armored reconnaissance and recon overlap naturally in the deep fight, but LAR is uniquely equipped to push deep and extract without relying on external lift or sustainment, supporting operations beyond a single frontage.

The stand-in sensor company concept is not a concept for the distant future. It is a working answer to today’s problem: how to turn legacy formations into lethal, relevant forces across all domains. Apache Company’s construct shows that with the right organization and fielded tools, a LAR unit can deliver the decisive advantage MAGTFs need: sensing early, striking fast, and shaping tempo in complex, contested terrain. It proves that innovation doesn’t always mean waiting on new platforms; it means rethinking how we fight with what we have. The LAR community’s evolution is a microcosm of the Corps-wide challenge: adapt fast, fight smarter, and build toward the future without waiting for the perfect solution. This is not about replacing cavalry, it is about making it and the MAGTF writ large matter in the fight ahead.

Tomorrow’s Fight

Capt Ellis awoke with a start and quietly replayed the dream where his legacy company was torn apart; unprepared for the battlefield he now faced. Reality would be different. He stepped into his enhanced LAV-C2 and oriented on the sensor displays and the common operational picture.

Hours before the enemy advance guard pushed toward Jõhvi, geospatial stand-off sensors flagged movement along likely avenues of approach. Tucked into hide sites with vehicles camouflaged, Apache’s reconnaissance platoon confirmed with Group-1 systems and set hasty ambushes to disrupt the axis of advance. As the column entered the kill zone, direct-fire systems killed the lead and trail vehicles, fixing the formation. At the same time, Group-2 platforms observed and adjusted long-range fires, streaming feeds to the fusion platoon and higher.

While the fight built ashore, the maritime picture stayed warm: Automatic Identification System and coastal radar returns, rapid reports, and Group-2 pay-loads over the water fed the battalion to track craft along the coast. A suspected grey-fleet vessel broke pattern north of Jõhvi; the cue moved from S-2 through fusion to the northern security screen. A UTV team maneuvered to the beach exits, found the landing sites cold, and laid obstacles and observation to deny a raid force its easy off-ramps.

Ten kilometers behind the FLOT (forward line of troops), security platoons screened in depth, watching the contact forward and reorienting on alternate approaches as the enemy tried to bypass the kill zone. In coordination with fusion, they finalized a rearward passage once reconnaissance platoon finished its harassment and shaping mission against the lead trace.

Inside the company’s architecture and surveillance and reconnaissance collection cell, Marines worked with the battalion S-2 (intelligence section) in near realtime: pushing critical data up and pulling refined intelligence down. Targets were packaged, prioritized, and effects queued for ultimate impact. At higher echelons, commanders saw rapid updates and live feeds through the shared portal. Decision cycles accelerated with expanded options made possible by a symbiotic relationship between sensors, intelligence, and higher echelon fires. In practice, the stand-in sensor construct bought time and space for follow-on forces now shifting from one area of operations to the next and shaping the fight before it fully arrived, ashore and along the coast.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Capt Marshall is the Company Commander of Company A, 2d Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, 2d MarDiv.

NOTES:

- Michael Kofman and Matthew Rojansky, “Russia’s Growing ‘Dark Fleet’: Risks for the Global Maritime Order,” Atlantic Council, September 30, 2025, https://www.atlanticcoun-cil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/russias-growing-dark-fleet-risks-for-the-global-maritime-order.

- Headquarters Marine Corps, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: 2020).

- John Dick, “From Concept to Capability–Building an Organic FPV Strike Team in the Ground Combat Element (Part I),” The CX File, July 9, 2025, https://thecxfile.substack. com/p/from-concept-to-capability-building.

- Brent Jurmu, Brandon Klewicki, and Mat-thew Tweedy, “Equip the Mobile Reconnaissance Battalion Now,” Marine Corps Gazette, May 2024, https://www.mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/Jurmu-May24-WEB.pdf.

- Philip Laing, “More Than a System: LAR as a Mindset” (master’s thesis, Marine Corps University, Command and Staff College, 2011).

- Jack Watling, The Arms of the Future: Technology and Close Combat in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023).