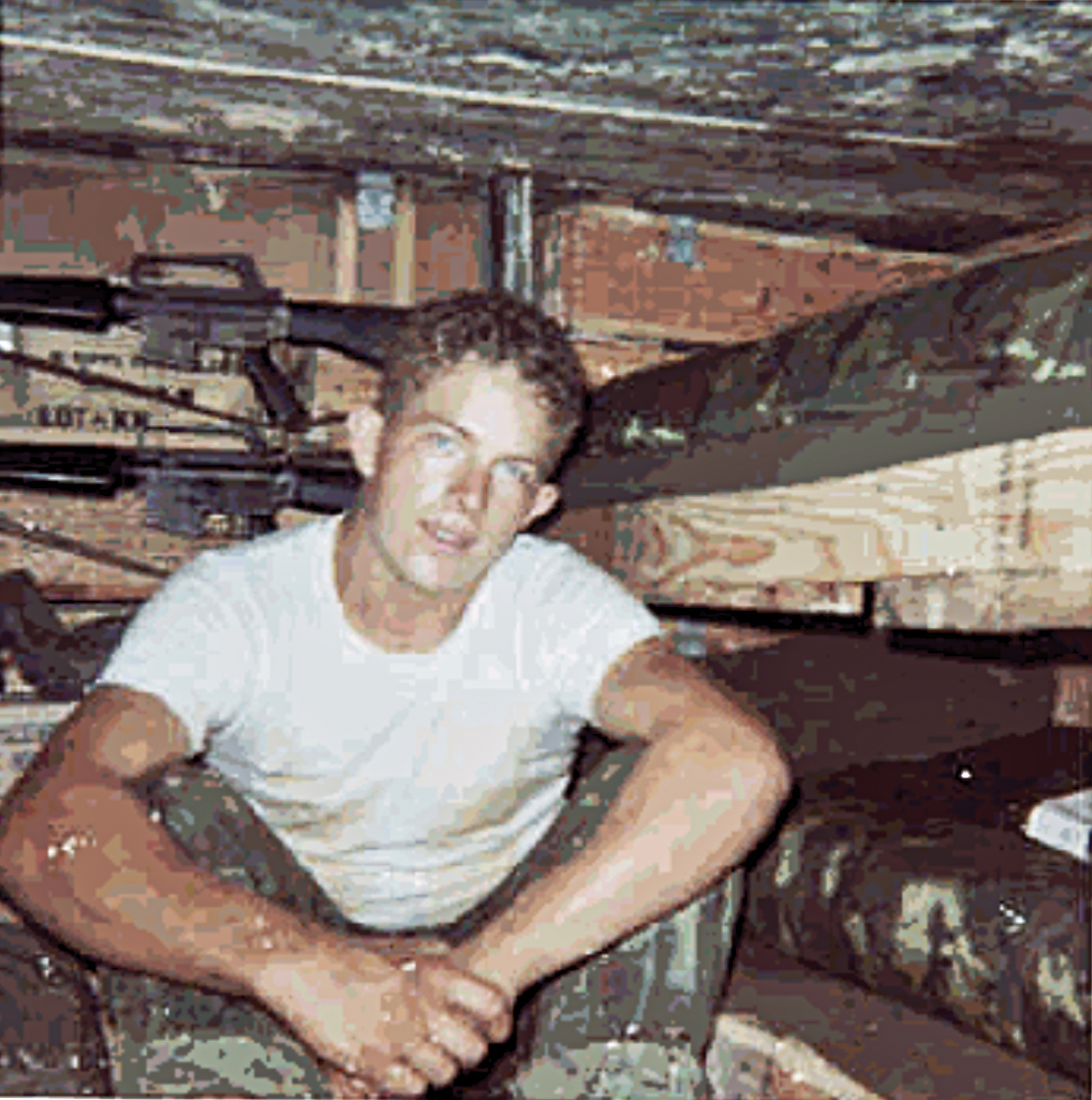

Dusk settled over the hilltop on Feb. 24, 1969. Lance Corporal Patrick “Mac” McWilliams examined the Marines assigned to him for listening post (LP) duty. All of them were green, recently arrived in country and shuttled out for their first stint in the bush. Mac’s four months in Vietnam made him an old salt in their eyes, with experience to help keep them alive. He previously spent time on the hill, and already acquainted himself with the menacing jungle beyond the perimeter. The grunts were exhausted from patrols over the last few days. Some in the company treated LP duty with complacency, despite the inherent danger being isolated outside the wire. Mac resolved to teach the new guys correctly. He passed out grenades and trip flares and performed final checks. The four-man team proceeded down a finger, beyond the final defensive web of wire and into enemy territory.

Mac found a spot 100 yards into the jungle and set up the radio. Private First Class Dennis Gardner moved farther ahead to set up a trip flare across a trail.

“If that thing goes off, we need someone to throw the first grenade,” Mac said.

“I used to play quarterback,” Gardner told him. “I’ll do it.”

For Mac and numerous other veterans from “Echo” Company, 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, their return to guard duty on the hill 10 days earlier proved apprehensive and unwelcome. In November 1968, their platoon scaled the mountainside to carve a remote base out of the Vietnamese jungle. They strung together C4 explosives and blew down trees in the rough shape of a landing zone (LZ). Helicopters lifted in heavy moving equipment to finish off the stumps and flatten the crest. Marines dug fighting holes and constructed bunkers out of old ammo boxes while more choppers offloaded a battery of 105mm howitzers into newly constructed gun pits. The position, named LZ Russell, became the newest fire support base in a nexus of interlocking artillery. Multiple hilltops similar to Russell blanketed the jungle, covering infantry operations along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Since Russell’s establishment, nearly 300 Marines continuously occupied the hill. Mac’s platoon departed to fight in other battles along Mutter’s Ridge and near Con Thien shortly after the artillery pieces arrived. They returned to Russell for their turn on guard duty less than three months later.

Six guns from “Hotel” Battery, 3/12, occupied the crest. They presented an attractive target for North Vietnamese Army (NVA) fire. The base sat in the remote northwestern corner of South Vietnam, a stone’s throw away from the DMZ and within view of the Laotian border. Daily ground operations in the vicinity generated fire missions around the clock. In the month of January 1969, the three 105mm batteries of 3/12 fired nearly 30,000 rounds. Totals from later months that year reached closer to 40,000 rounds.

Three gun pits surrounded the main LZ at the summit. The remaining three stretched out down a long finger protruding east. The entire position lay exposed to enemy view. Enemy soldiers probed the grunt perimeter and fired mortars sporadically around the hill, mapping out Marine positions and registering their fires. By the end of February, platoons from Companies E and F, 2/4, and one platoon from Co K, 3/4, defended Russell’s perimeter around Hotel Battery.

Shortly after midnight on Feb. 25, a fire mission crackled to life from the radio. Fire Support Base (FSB) Neville, located just 5 miles west, called urgently for help. The voice on the other end reported the news most dreaded by Marines on an isolated hill; NVA sappers penetrated the wire and overran the base. Hotel Battery sprang to action. All six guns opened fire on pre-registered targets surrounding Neville. For three hours, the battery pounded Neville’s entire perimeter, firing over 300 rounds of high explosives or illumination. The artillerymen endured the work, many without even knowing what was happening on the nearby outpost. To them, it was just another midnight fire mission.

The roaring howitzers kept Mac and his Marines awake at the LP. They rotated through radio watch as the hours passed and tried to sleep. Around 4 a.m., the fire mission ceased and the jungle fell quiet. Before their ears adjusted to the silence, without any warning, mortar rounds impacted behind them inside the perimeter at the top of the hill. Mac, Gardner, and the others bolted upright and clinched their rifles. A chorus of small arms fire punctuated the space between explosions. The Marines understood, without a doubt, that NVA soldiers broke through the perimeter and were already overrunning LZ Russell, even under their own mortar fire.

Mac tried to raise the command post (CP) but received no reply. He ordered the others to grab their gear and move out. He figured their original position had been spotted and set up again near a large fallen tree. Gardner hit the deck, sheltered behind the uprooted base. The trip flare he placed earlier in the night suddenly ignited down the trail in front of him. A blinding light illuminated numerous NVA moving up the hill. Gardner pulled the pin on his grenade, cocked his arm back, and let it fly. The perfect toss landed on the trail and exploded amongst an enemy group. More unseen NVA opened fire in the LP’s direction. The four Marines fired rapidly at sounds of movement in the surrounding jungle. Heavy impacts from a .50-caliber machine gun threw up dirt in mini explosions all around them. With nowhere to run and no one to help, the LP stayed put and fought for their lives. They were not alone in their plight, as the sounds of battle from the hilltop increased in a terrifying pitch.

Lance Corporal Bruce Brinke stood radio watch in the platoon CP bunker, having checked in with the LP throughout the night. When the howitzers ceased fire, the “Thoomp, thoomp, thoomp,” of mortars in the distance resonated soon after. The first explosion struck right outside the bunker, with a second scoring a direct hit. Brinke and the other Marines inside dove for cover as explosions enveloped the hill. He landed halfway through the door of another adjacent room inside the bunker. A satchel charge flew through the open bunker door, falling next to Brinke’s platoon commander, Second Lieutenant William Hunt. The bunker erupted in a ball of fire. Shrapnel ripped a large gash through Brinke’s leg, but the wall of the adjacent room protected his upper half. He tried to move as the bunker burned and collapsed around him. In the chaos, he discovered the remains of Hunt, who absorbed much of the blast and died instantly.

Another Marine assisted Brinke outside the burning structure. As they exited, muzzle flashes pierced the darkness within inches of Brinke’s face. An NVA sapper waited outside against the bunker wall within arm’s reach. He unloaded on Brinke and his companion as they walked out. The two Marines fell back, hitting the ground outside the doorway. Miraculously, Brinke suffered only one gunshot in the arm near his shoulder. The other Marine was hit once in his leg. The enemy soldier scampered off to find his next victims, believing the two Marines were dead. Brinke lay bleeding from his wounds, waiting for another enemy to find him and finish the job.

Corporal Alvin Winchell took shelter in a fighting hole with his squad as the mortars impacted. A bunker nearby suddenly exploded and collapsed, burying six Marines inside. In the flashes of light, Winchell saw NVA sappers advancing up the hill under the fire of their own mortars. Some of the enemy carried no weapons, but cradled explosive satchel charges in their arms and tossed them in each Marine bunker they passed. Winchell’s platoon sergeant ordered him to move his squad down the hill to a breach in the wire where sappers streamed through. Winchell gathered his machine gun team and sprinted toward a bunker near the breach. He set up the gun on the roof and scanned for targets.

“You could only see shadows in the dark until somebody popped up a flare,” Winchell remembered. “You don’t know if it’s a Marine or NVA, but it was just like ants coming up that hill.”

The machine-gun team opened fire on the shadows swarming from the jungle. The rattle of violence filled the air behind Winchell as the NVA overran LZ Russell and the battle devolved into utter chaos. Wounded and dying men screamed for help. American and Vietnamese weapons chattered back and forth. Darkness veiled the horrifying realities of hand-to-hand combat from a broader view. Through this phase of intensely personal killing, every Marine on the hill experienced his own unique version of the battle, and cemented in their minds the memories that would haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Numerous stories from the savage fighting that night later emerged. The overwhelming volume of simultaneous events, the darkness and the unmitigated confusion shrouded the details. Many of the Marines who inspired their legend are now gone. To many more, Feb. 25, 1969, remains a night too painful to discuss, even 55 years later. The stories that have come to light illuminate the ferocity of the battle, and how the actions of individual Marines across the hill turned the tide against the enemy.

As Brinke lay on the ground, after being blown up and shot outside his bunker, Gunnery Sergeant Pedro Balignasay eventually passed by. By this point in his career, Balignasay earned renown as an old breed legend of the Corps. The Marines affectionately referred to him as, “Gunny Huk,” in honor of his Filipino roots. Born in the Philippines in 1927, Balignasay immigrated to the U.S. and enlisted in the Marine Corps. He served in WW II, Korea, and saw three combat deployments in Vietnam before he retired in 1973. He was widely known by the grunts of 2/4 for his weapon of choice, carried at all times; a Filipino bolo knife.

“Hey Gunny Huk! Can you help me?” Brinke cried. “I need to get up!”

Balignasay approached. He held his bolo knife in one hand and a shotgun in the other. He hastily triaged Brinke and saw that he would survive, and he lay in a covered position.

“Sorry Marine, I can’t do anything more for you. I gotta go kill some NVA.”

Balignasay’s Silver Star citation describes multiple times he was wounded that night as he roamed the hill directing uninjured Marines or helping move the wounded to cover. It alludes to his instrumental role in, “killing numerous enemy and successfully defending their position.” At least five of these enemy reportedly fell victim to Gunny Huk’s beloved bolo.

Captain Albert Hill, the Echo Co Commander, survived the initial barrage of mortars and satchel charges and entered the hand-to-hand clash over the hill. At one point, Hill pulled the pin on a grenade to hurl at an enemy. At that very moment, another NVA sapper rushed him. Hill locked into mortal combat, the live grenade still clutched in his hand. Unable to let go, lest he blow himself up alongside the sapper, Hill prevailed over his foe and used the grenade like a rock in his hand to bludgeon the enemy to death. Like Balignasay, Hill received a Silver Star for his role in defending the hill.

LCpl Rick Davis served as an artilleryman with Hotel Battery. His reinforced bunker withstood multiple direct hits during mortar barrage, and a thick wool blanket hung across the doorway deflected satchel charges tossed by NVA sappers. The bombs detonated outside, disorienting the Marines, but leaving them unharmed. Davis searched the bunker for a rifle as an NVA officer boldly barked out orders from somewhere nearby. Davis and the other Marines pushed through the doorway with rifles ready. They killed several NVA outside their bunker as they moved a short distance over the parapet into their gun pit.

The enemy soldier shouting orders stood on the parapet wall. Davis fired several rounds into him. Another Marine shooting from the opposite direction fired into the soldier at the same time, and he fell dead. The Marines arranged in a small defensive position around the gun. Wounded men called out for help all around them. Amidst the explosions, gun fire, and hand-to-hand combat, Davis set out with the others to rescue them. They recovered several Marines, some lying wounded around their gun pits, others partially buried inside the collapsed bunkers.

When not preoccupied with beating back the NVA sappers, many like Davis undertook the enormous effort of saving the lives of their fellow Marines. Doc Rich Woy, a corpsman assigned to Brinke’s 3rd platoon, found Brinke lying outside the bunker door where he fell. Woy bandaged his wounds before proceeding onto other patients.

“I could see Doc Woy working on one guy up by a mortar pit behind us,” said Winchell, recalling a scene from memory as his squad held the line. “Doc had a tube in his throat trying to keep him alive.”

Woy survived the same satchel charge that killed Hunt and wounded Brinke in the CP bunker. He extricated another platoon corpsman from the CP and moved him to safety near Winchell’s squad. From there, he worked his way up and down the hill treating wounded Marines. Eventually, he remained at the LZ triaging and loading critical patients on medevac choppers. For his tireless work, Woy received a Silver Star.

Many of the wounded lay trapped in bunkers, collapsed from the onslaught of satchel charges. Private Michael Harvey, a radio operator with 2/4, discovered two partially buried Marines. He worked feverishly removing the heavy debris. A bullet pierced a nearby fuel drum, lighting it on fire. Without hesitation, Harvey threw himself across the wounded Marines as the drum exploded. His body shielded them from the resulting fireball. He died as a result of the injuries he sustained. For his incredible actions, Harvey was posthumously awarded the Silver Star.

Private First Class William Castillo, a mortarman with 2/4, freed several Marines from a bunker destroyed in the initial moments of the attack, then single-handedly returned to firing his mortar. Incoming rounds blew him off the tube twice, but he got up and returned each time to continue firing. When another bunker exploded and started burning, Castillo ran to the entryway and pressed ahead through a thick cloud of black smoke rolling out the door. He discovered five Marines inside, blinded by the smoke and in shock. Castillo led all five outside to safety. He survived the night, and for his heroic actions, received the Navy Cross.

Winchell remained with his squad on the perimeter mowing down sappers as they appeared from the jungle. For his courage and leadership over his squad through the battle, Winchell received a Bronze Star with combat “V.” He heard a scream for help up the hill behind him. He moved toward the voice and found the severely wounded corpsman moved to safety by Doc Woy. In excruciating pain, the corpsman instructed Winchell to grab two morphine syrettes from his bag and inject them into his buttocks. Winchell administered the medication, then rubbed his finger in the Doc’s blood and drew a “M” on his forehead. A new and deafening roar of explosions suddenly split Winchell’s ears and lit up the jungle around him. Friendly artillery fire, similar to the barrage Hotel Battery provided for FSB Neville earlier in the night, began raining down.

“It sounded like a freight train coming in,” Winchell recalled. “They rang the hill all around the perimeter. Some landed inside. I looked at the corpsman and told him, ‘I think we’re f—ked.’ ”

Mac, Gardner and the others on the LP willed their bodies into the dirt through the barrage. Still outside the wire, they lay directly under the intended impact zone.

“It was raining hell fire!” said Gardner. “Arty was landing all around us. The ground shook, the darkness lit up, and shrapnel was flying from the explosions striking the trees. All we could do was hug the ground and hope a round didn’t land on top of us!”

After what seemed an eternity, dawn broke mercifully over the hilltop. The friendly barrage ceased, and the fight for LZ Russell trailed off. The only NVA remaining inside the wire lay dead. The rest vanished back into the jungle. The morning revealed the battle’s horrific aftermath. The enemy successfully disabled three of the six howitzers. Bunkers around the hill crumbled in ruins with screaming Marines trapped inside. American and Vietnamese bodies lay intermingled in a grotesque spectacle attesting to the savage combat. Unidentifiable body parts littered the hill, remnants of the many satchel charges employed by the sappers with devastating effect.

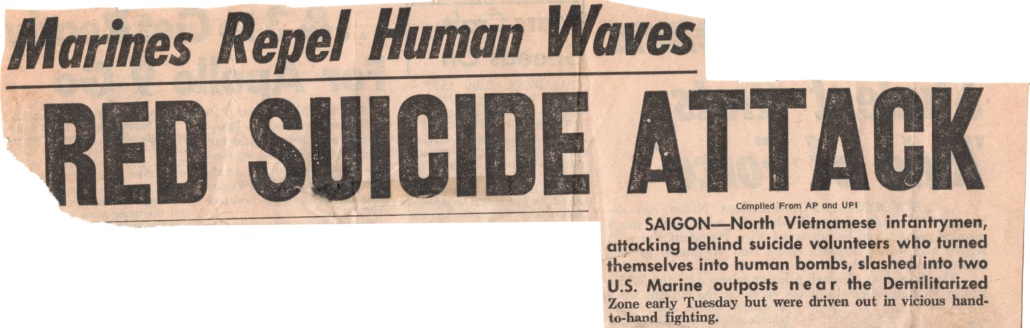

This headline ran in Stars and Stripes within a week after the attack, succinctly describing the horror the Marines faced.

Miraculously, the four Marines on LP duty survived the night unscathed. They remained outside the wire waiting permission to reenter friendly lines, lest they be mistaken as enemy and gunned down. Their anxiety soared as they sat in the quiet jungle. The peace was broken by a lone Marine somewhere nearby up the hill, calling out to God for help. Finally, they received the all clear.

The body of an NVA sapper shot through the head greeted them as they passed through the wire. Almost immediately, Mac directed the others toward a collapsed bunker to retrieve the body of a Marine buried inside. Gardner discovered the bunker was his own, which he shared with three others. They moved sand bags and ammo boxes to create an entrance. Inside, Gardner found the remains of another Marine from his squad who was up for LP duty the previous night, but Gardner went in his place. He suffered the initial onslaught of survivor’s guilt as he dug the Marine out and dragged the body up the hill to the LZ for evacuation. His squad mate was the first dead body Gardner had ever touched. Afterwards, Gardner and the others continued from bunker to bunker carrying dead Marines to the top of the hill.

The LZ shrank as bodies collected near the crest. Dead Marines were lined up awaiting their turn for evacuation, with dead NVA stacked nearby. Marines and corpsman triaged the wounded for evacuation as helicopters trickled down through a thick haze that settled over the hill. Twenty-nine Marines and Navy corpsmen were dead. Nearly 80 more were wounded. Those who remained piled the enemy dead high on a cargo net in an unsuccessful attempt to lift them from the hill under the belly of a helicopter. Finally, Marines were forced to toss the bodies over the steepest side of the hill to be burned. The helicopter squadrons stretched thin as they simultaneously evacuated casualties from LZ Russell and the fight at FSB Neville, where 14 died and almost 30 were wounded. In one night between the two hills, the price paid by the Marines and Navy corpsmen defending them amounted to 43 killed, and over 100 wounded.

In the weeks following Feb. 25, the infantry platoons that guarded the hill moved on quickly. In typical grunt fashion, no significant period of rest or reflection could be afforded. The Marines moved on to other hilltops, other jungles, other battles. For many, the experience at LZ Russell stood out as a defining moment of their time in combat and would forever dominate their dreams. In contrast, many artillerymen of Hotel Battery remained at LZ Russell through the spring and summer of 1969, daily reliving the fight they had all survived.

“I never slept after that night,” said Rick Davis, who remained on the hill with Hotel Battery for several months after the attack. “I just never would have put it past the NVA to come back and try to finish off the rest of us. We got resupply of some new guns, new ammo, new people. There was a lot of work to do.”

Some Marines, like LCpl Ken Heins, spent nearly their entire 13-month deployment on the hill. During the battle, Heins was blown up inside his bunker and trapped after he blacked out. He came to after daybreak when Marines entered the ruins and rescued him. Other Marines inside with him reported that NVA soldiers had entered the bunker during the night and stolen items off them as they played dead. Miraculously unwounded, Heins stayed on the hill and helped rebuild some of the bunkers where his friends were killed or maimed. The artillerymen started carrying loaded rifles and grenades to defend themselves at a moment’s notice, rather than relying solely on the grunts for protection. The NVA continued probing the lines and firing sporadically into the perimeter, but another assault like the night of Feb. 25 never materialized.

The battery fired thousands of rounds per month as the year wore on, staying busier than they had ever been. At one point, the work so thoroughly exhausted Heins that he slept uninterrupted through the awe-inspiring and earth-quaking devastation wrought by a nearby B-52 “arc light” bombing run. In September, the fire missions unexpectedly came to an abrupt and definitive halt. The Marines received orders to vacate the hill and destroy the base. Reasoning behind the decision failed to disseminate through the ranks. To a Marine like Heins, after spending his entire deployment on the hill, surviving the February assault, and grieving the friends he’d lost there, the abandonment of LZ Russell made all of it feel like a tragic waste.

Hotel Battery prepared their guns and equipment to be hauled out. Engineers rigged explosives to all the bunkers and piled high the extra powder bags, fuel, ammo, and any other gear condemned to destruction. They drenched everything with gasoline in preparation for the great conflagration that would render the hilltop useless to the NVA. On Sept. 21, Heins loaded the last of his gear onto a helicopter and climbed aboard. LZ Russell shrank beneath him as the chopper ascended. Without warning, a massive explosion detonated on the LZ. Heins felt and heard the “BOOM” over the sound of the helicopter. A mushroom cloud expanded into the sky.

“Holy shit!” he yelled. “They just blew the hill up! They didn’t leave us much time to get the hell out of the way!”

When the chopper landed, Heins learned the explosion happened prematurely, and by accident. Reportedly, a Vietnamese Kit Carson Scout on the LZ flicked a burning cigarette butt into a pile of powder bags. The powder ignited, sparking a monumental chain of explosions. Two Marines and two Kit Carson Scouts perished. Numerous others were severely wounded. One Marine, PFC James W. Jackson Jr., was evacuated to a hospital in Quang Tri alongside the other wounded, but somehow mysteriously vanished from the emergency room. Investigators never discovered any evidence or sign of him, and to this day, Jackson is listed as missing in action, presumed dead. The victims of Sept. 21, 1969, marked the tragic ending to the existence of LZ Russell.

Survivors fought to move on from the battle. Other veterans from Vietnam or later wars who endured similarly horrific events are the only ones who can truly understand the struggle these men endured. They fought for a return to normal life. They fought for their families and fought for themselves. Today, even five and a half decades later, they still face the demons of LZ Russell on a daily basis. Tragically, a few of these veterans ended their own lives, becoming the last victims claimed by the long-forgotten hill.

“There are veterans from LZ Russell all around the country, and they are all wounded,” reflected Rick Davis. “They’ve been wounded for a lot of years, and everybody is on a mission to help everybody else. Everyone saw what happened that night in 100 different ways and has been affected differently. There have been divorces, people getting fired and losing everything they have, people getting sick, committing suicide, families left with questions. There was a lot of stuff going on, and it was a mess. Somebody had to pay the price for what happened that night. We’ve been paying it ever since.”

In the late 1990s, a Marine from Hotel Battery named Skip Poindexter published a website in memory of LZ Russell. The site evolved into a repository of photographs and written memories of veterans who spent time on the hill. In August 2000, the LZ Russell Association was officially founded, with Heins as president. The organization scheduled the first reunion of LZ Russell veterans in Las Vegas. Marines gathered from around the country. For some, the initial excitement faded quickly as they sat face to face with other veterans, some of whom they had not seen since Feb. 25, 1969.

For years, they buried memories that they hesitated to unearth. Old animosities between the artillery battery and the infantry units reared. The Marines spent their lives after Vietnam refusing to speak of the events with people who could never understand them, and now suddenly faced the only ones who could. After a time, and with enough alcohol, the tension dissipated. The Marines pieced together the puzzle of the battle, filling in gaps for each other that had bothered them for years. More reunions took place, aiding greatly in the healing process. For numerous veterans of LZ Russell, however, attending the reunions and the passage of time remains inadequate, and they refuse to discuss the battle to this day.

Heins returned to Vietnam on several occasions in the years after the war. On five different trips, he scaled the old hill back to the top where LZ Russell once stood.

“Personally, I feel like half of me died up there.”

In this sentiment, Heins is not alone. On two of his trips to the hill, Heins took with him the ashes of other LZ Russell survivors to spread on the hill. Their final wishes were to be reunited with their brothers lost there, and the part of their youth that never returned home.

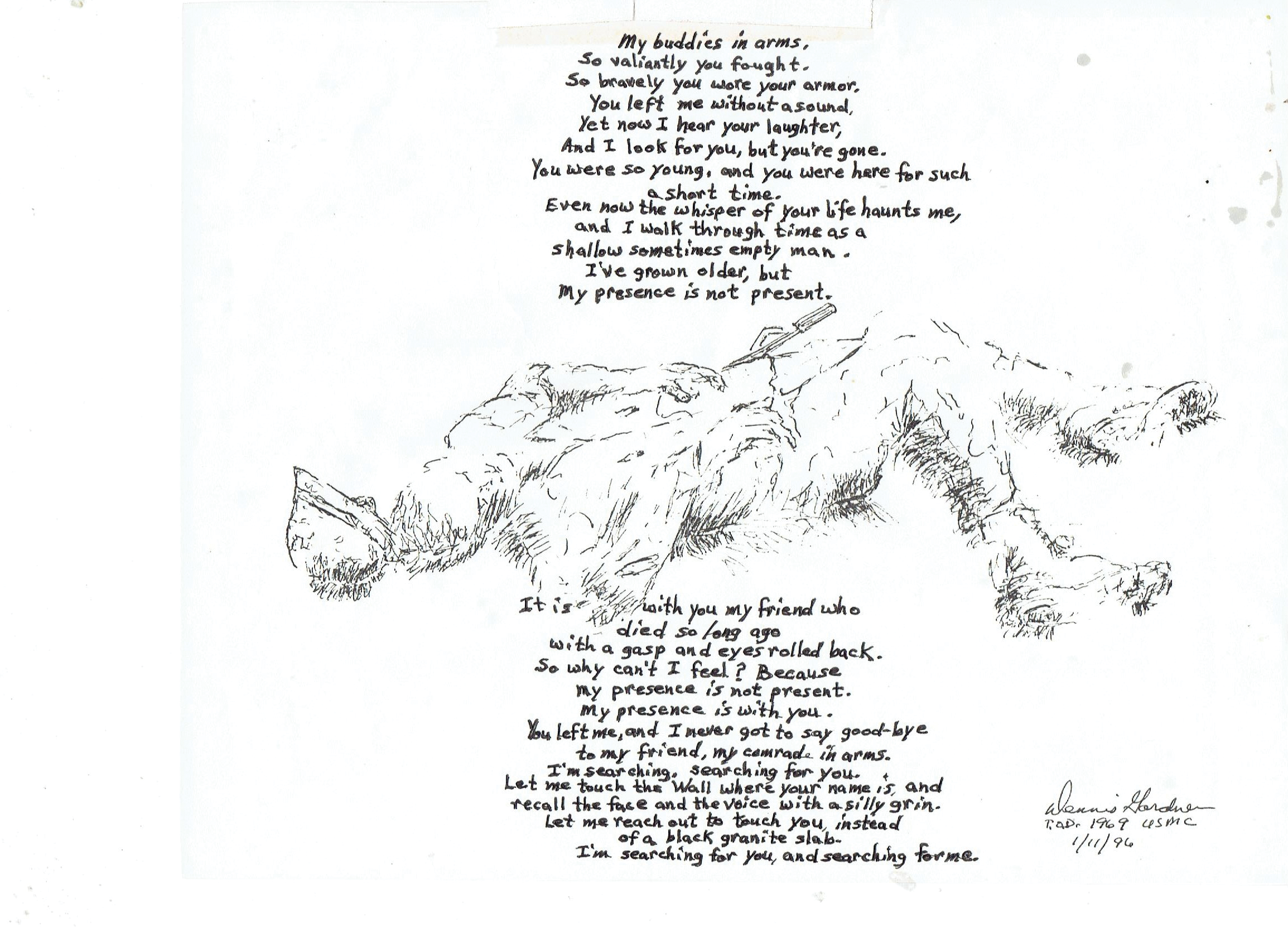

“It is with you, my friend,

who died so long ago

with a gasp and eyes rolled back.

So why can’t I feel?

Because my presence is not present.

My presence is with you…

I’m searching, searching for you.

Let me touch ‘The Wall’ where your name is,

and recall the face and the voice with a silly grin.

Let me reach out and touch you,

instead of a black granite slab.

I’m searching for you, and searching for me.”

(Poem by Dennis Gardner).

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.