Editor’s note: This story originally was published in June of 2018. It was re-published in recognition of National Korean War Veterans Armistice Day on July 27.

Twin siblings enjoy an intrinsic connection. Countless studies have been conducted on their similarities, brain patterns, development, even twin telepathy—yet their bond appears more spiritual than scientific. One could argue identical twins could not be more inseparable or alike. Two such brothers from the Greatest Generation found a way to forge an even stronger bond, becoming brothers in arms in the United States Marine Corps.

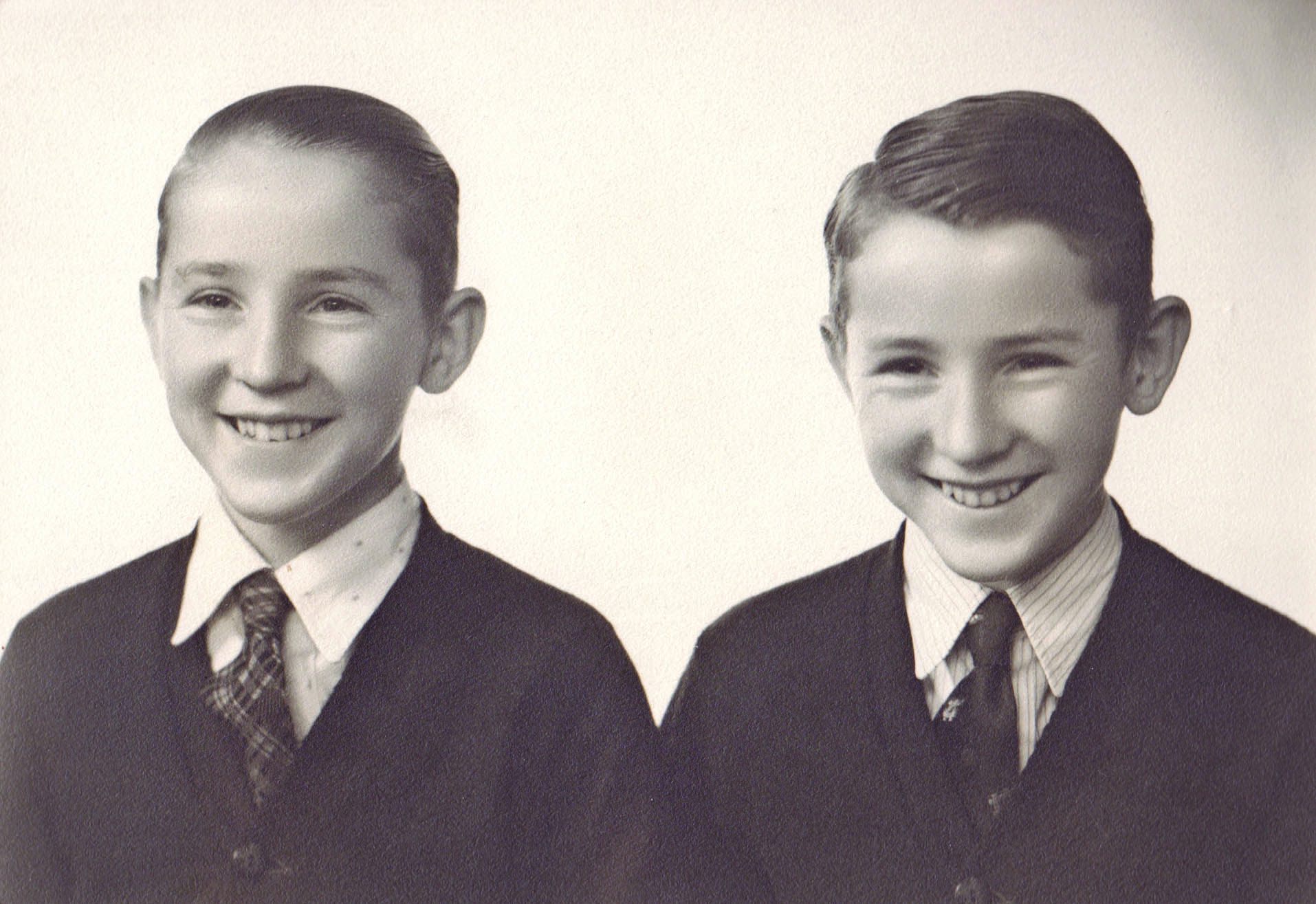

William and Robert Thosath were born on Dec. 7, 1925. Their father, Perry, was a first-generation American whose parents immigrated to Spokane, Wash., from Norway. He married his sweetheart, Alice, and settled into family life. By 1925, a toddler named James already roamed their small house. Alice became pregnant again and went into labor, delivering twins in their home. The birth was attended by her Norwegian mother-in-law. William was born first.

Recognizing Alice was not through with the delivery, Perry’s surprised mother scolded him. “My goodness Perry, you always overdo everything!” Twenty minutes later, Robert followed. Thus, “Bill” and “Bob” entered the family.

The twins’ childhood proved typical of the day, as the family endured ongoing financial struggle through the Great Depression. Even so, it was a happy life, and the boys were inseparable. There was no William or Robert—it was always Bill and Bob. They worked on cars at their father’s auto shop and performed other odd jobs to help bring in money. When not working, they went hunting, fishing and camping in the woods around Spokane. They perfected “twin tricks” on their friends, teachers or family, with one twin posing as the other.

The only thing harder than separating them was telling them apart.

Though identical in appearance, the twins maintained their differences. Bill took after his father, serious and soft-spoken. Bob, on the other hand, was more whimsical and loved poetry and music. On one occasion at the height of the Depression, the twins had been working long hours, scraping together barely enough for their family to get by. That evening, Bob returned home and revealed a handful of coins to his mother. He announced with a smile that he earned the extra change that day and was taking her dancing. For that night at least, any worry over the lack of milk in the house or the absence of an indoor bathroom took a back seat.

Bill and Bob entered Lewis and Clark High School in the early 1940s. On Dec. 7, 1941, as they celebrated their 16th birthday, 3,000 miles away the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, sparking an unstoppable chain of events that would alter the lives of millions of Americans, including the Thosath twins.

As the fighting heated up, the brothers’ patriotic fervor burned inside. They drudged through high school, watching the men of Spokane depart for war. Their older brother James enlisted in the Army and was sent to the Pacific in 1943. Two of their uncles joined and went overseas as well. The twins yearned to fight for their country and prepared to drop out of school to enlist.

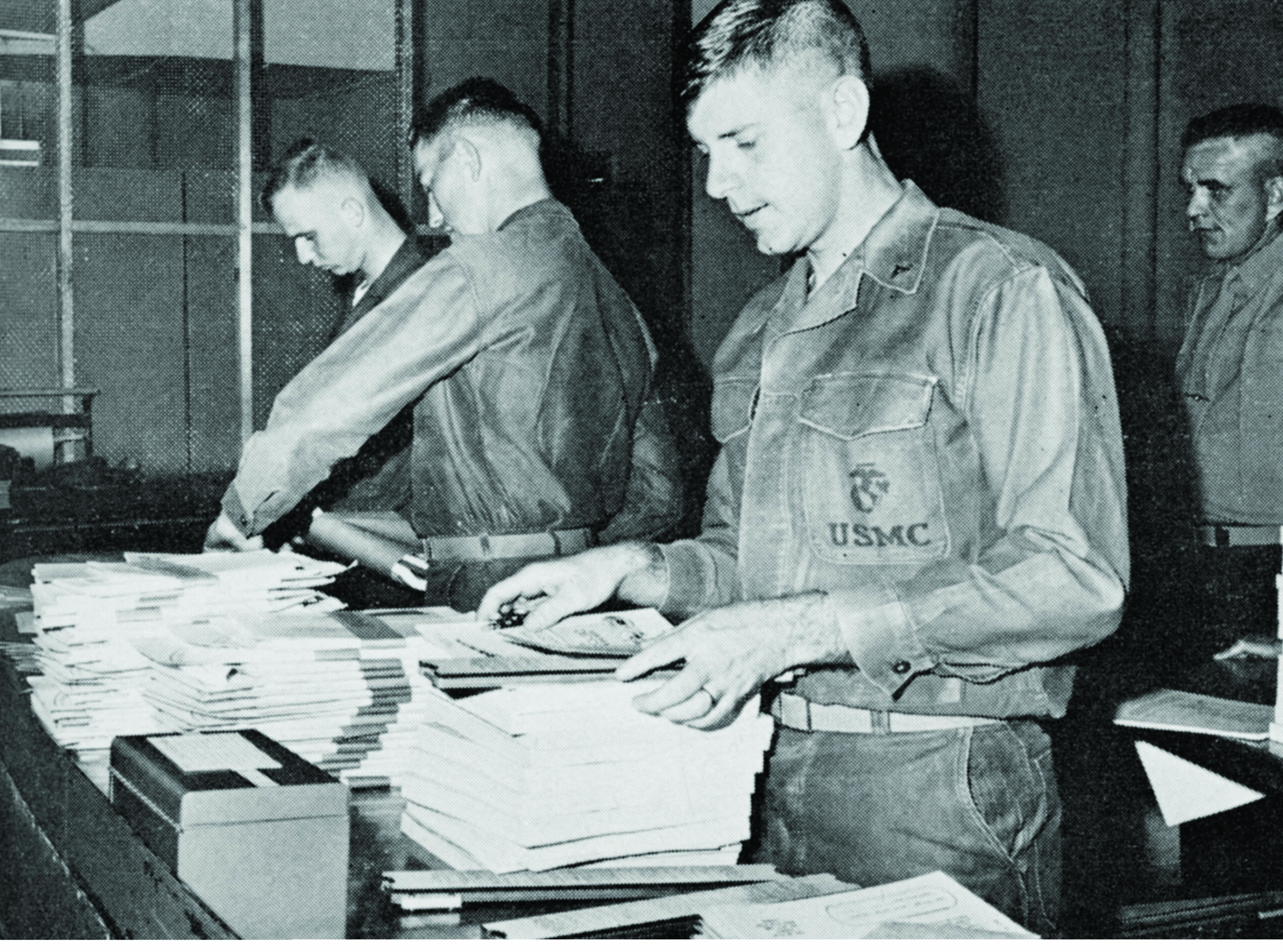

On their 18th birthday, Bill and Bob dragged their parents to the Marine recruiter’s office. Standing 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighing less than 120 pounds apiece, the recruiter discovered the twins did not meet the minimum weight requirements for the Corps. He sat the boys down, passed them a bunch of bananas, and told them to start eating. Several minutes and several bananas later, the twins’ full bellies tipped the scales in their favor. Their parents signed the enlistment papers and shortly the twins were off for recruit training in San Diego.

Alice and Perry Thosath returned home, without their sons, to inescapable silence. Their younger daughter Dolores (called “Dilly”) remained home with them, but all the boys were gone. Alice saw the increasingly common “service flags” hanging in windows throughout town representing sons at war. She hung one of her own in their window, with three stars paying mute tribute to her own sacrifice.

By the end of 1944, the twins were assigned to the infantry serving with the 1st Battalion, 26th Marines. They set sail to join the thousands of Marines already engaged in the Pacific. Even with their late entry into the war, the Thosath boys would not be spared from the carnage. Their first experience together in combat took place at the landmark battle of Iwo Jima.

Bill and Bob hit the beach on D-day following the initial assault waves. U.S. naval bombardment cleared the entire area of any natural cover, leaving only the bomb craters as protection from Japanese fire. Advancing inland, they encountered numerous enemy pillboxes and land mines, but the battalion sustained significant casualties from the unceasing artillery and mortars raining down on top of them.

The twins had joined the Marines, the infantry, and the battle just as they had anything in life—together. Now fighting the Japanese side by side, they questioned this instinct. As the unit battled inland, Bill and Bob split up between two companies within the battalion. The violence surrounding them made survival uncertain. They hoped some distance between them might decrease the likelihood of getting hit at the same time.

They continued for days, arching across the north side of the island. To root out the entrenched Japanese, exposed infantry drew fire to pinpoint their location, then tanks and mortars blew them to pieces. The twins’ battalion played a critical role in the final phase of the battle, destroying the last enemy hold out at Kitano Point. They witnessed vicious, point-blank fighting, as the last remnants of the Japanese fought to the death.

Once Iwo Jima was secured, Bill and Bob took part in a massive “mopping up” operation, visiting numerous islands, hunting for any remaining Japanese. Nothing encountered during this period compared to their experience on Iwo. Bob wrote home to his parents:

“Dear Folks,

How are you? Bill and I are fine. I know you are really worried by now … The reason I haven’t said much about Iwo is we didn’t want to worry you. We had extra good mail service then and kept you pretty well bluffed. There isn’t anything to worry about now. I don’t like to talk much about Iwo because it was a living hell.”

The twins took part in patrols searching for, “[Japanese], land mines, crashed American planes, or anything in particular,” Bob wrote. In the Palau Islands, Bill and Bob patrolled the island of Koror. On one occasion, they climbed down to the entrance of a cave and crept cautiously as they noticed the barrel of a Japanese machine gun sticking out. As the gun came fully into view, they saw the bare bones of two skeletal hands still clutching the grips. They entered the cave and found a Japanese skeleton sitting behind the gun, ready to fire. They pondered this morbid spectacle, making mental note of the ammunition—still in perfect lethal condition—and the fanatic soldier, who continued his fight even from the afterlife.

The living enemy they found were corralled in a stockade, then transferred back to Japan.

As they moved from island to island, Bob wrote a series of poems in addition to his letters home.

“The Army can have its khaki,

the Navy can have its whites;

but I will take the outfit

that knows how to fight.

We have fought for our country

in every foreign land,

for our liberty and freedom,

and we made a gallant stand.

Though odds were against us,

both big and small,

we never let you down

where any duty called.

Battles we have won,

none have we lost.

No matter what the danger,

no matter what the cost.

Everyone knows our motto,

everyone knows our will.

For the [Japanese] who know it best: kill, kill, kill!

We have won the battle,

the worst ever seen.

We well earned the title,

United States Marines.

In God we trust wherever he may be. Over the land, in the air, and on the sea.”

The twins eventually sailed to Japan, along with their captives, and remained there on occupation duty. With the war in its final stages, they longed to return home to Spokane. It had been 18 months since they last saw their family.

“Wish us luck, and it won’t be too long before we will see each other,” Bob wrote his parents. “Pop, you can start looking for a new car now … Mom can start digging out her recipes and get ready to cook. Dilly better get ready to be teased again. All my love, Bob.”

To emphasize the point, he added a postscript:

“P.S. You’re the best family a fellow wants and all hell can’t keep me from coming back.”

Bob squeezed a final line to his parents at the bottom of the page under the postscript:

“Please excuse the language, but I meant it.”

After nearly two years, the Thosath twins returned home as corporals in July 1946. They settled into their post-war civilian lives nicely. Both took jobs and married. Bob’s wife, Jean, soon became pregnant with a daughter, Jackie. In early 1950, the twins also gained another sister. Their mother Alice gave birth to her fifth child, a daughter named Patricia. As the family expanded and the brothers looked to the future, they remained proud of their service in the war and even prouder to call themselves Marines.

In July 1950, almost exactly four years after the twins returned home, another chain of events began that would dictate the brothers’ destiny for the second time. Half a world away, the armies of North Korea invaded South Korea, invoking the swift military response of the United Nations.

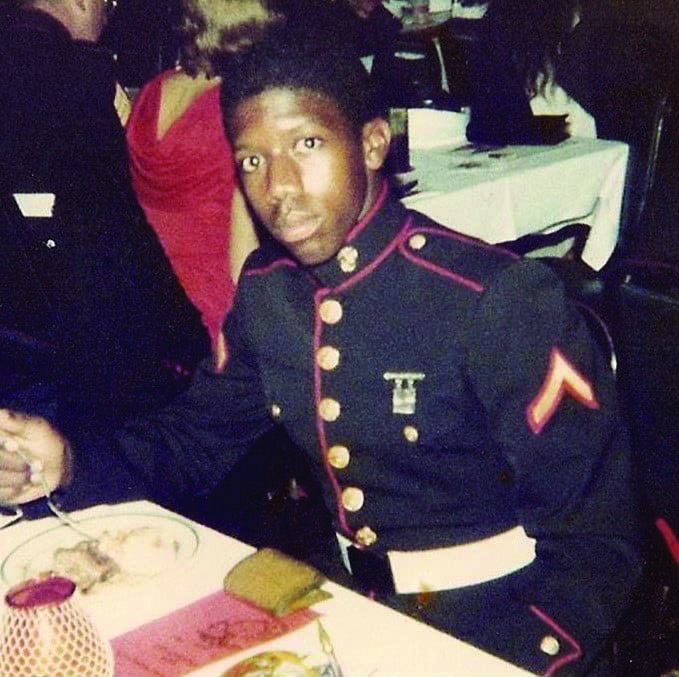

The country prepared for war, and the boys again could not contain their patriotism. “They were hell-bent on joining the Marines,” said their youngest sister, Pat, in a recent interview. “They go through the World War II experience and come home, and they aren’t done yet.” Ultimately, they reasoned if they had survived the World War, Korea would feel like a vacation. Bill and Bob took the oath of enlistment for the second time, and were returned to active duty.

Bob reassured his distraught mother and wife. He tried to convince them that Korea would be nothing compared to what they had already been through. The boys would be home before they knew it. For Bob’s wife, Jean, the news proved most untimely. She was pregnant again, and Bob would not be there for the baby’s birth.

The twins returned to the infantry with the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, and sailed for Korea in September. Learning from their combat experience on Iwo Jima, they again decided to split up. Bill served with “George” Company as an infantry platoon sergeant. Bob led a section of mortars in Item Co.

The Marines of 3/7 arrived at Inchon toward the end of September 1950. The twins’ first Korean combat experience came quickly while recapturing Seoul. Following this short drive inland, 3/7 and the entire 1st Marine Division began planning their next expedition. They would sail to the opposite side of the Korean peninsula and push north toward the border with China.

“Hi there everybody, how are you today?” Bob wrote in a letter to his parents as they waited to re-embark. “I have some news for you, something that will make you and dad proud of us. My [lieutenant] and I heard through the grapevine that Bill too, because of the way we acted and handled our men under fire, we are both sergeants. So address our letters respectively Sgt R.L. Thosath. Good news, don’t you think? Both of us are in different outfits and made it at the same time. Funny in a way.”

The scuttlebutt going around had the Marines doing all sorts of things, and Bob’s take on the upcoming mission was no exception. “We are sailing in the morning for combat again. Now keep this a secret until you read it in the papers. We are landing 14 miles from Russia, then making a 114-mile dash to the North Korean capital which is our objective. From there they better send us to a rest camp. We sure need it. We are all underweight. We just have the clothes on our backs. Shoes are about worn out. Oh well, enough of our trouble … .”

While his geography and mileage were inaccurate, there was no question about it. The Marines knew something big was coming—something important—and they were going to be at the center. As he commented on the physical condition of his men, he could not possibly have imagined the horror that waited for them in the hills surrounding their next objective.

“Now, don’t worry. Tell grandma hello. Also Jim and Lucy and the kids … Maybe we might, but no promises, be heading home after this mission. I miss you all and love you all … Your devoted son always with my love, Bob.”

The Marines packed their gear, boarded the ship, and set sail. Commanders finalized their plans for the mission. They would push the North Korean Army to the Yalu River border with China and capture a large man-made lake known as the Chosin Reservoir.

The twins, along with 25,000 other Marines, began their drive north from the coast. They marched up the single, unpaved road that served as the only way into or out of the reservoir. They understood they were marching into the mountains, in winter, into one of the coldest known parts of North Korea.

Neither this knowledge, nor any amount of cold-weather gear, could adequately prepare them for the harsh conditions they faced. Temperatures plummeted below zero, freezing water, food, weapons and Marines. Stiff winds whipped exposed skin and cut through all layers of clothing. Periodic snowfall added to the misery.

Another enemy lurking around the reservoir proved far less understood or anticipated than the cold. Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) observed the 1stMarDiv moving toward their border. They were already fighting alongside the North Koreans, but this invasion precipitated the mass movement of Chinese troops south of the Yalu River against the Americans. As the Marines battled through any resistance along the road north, more than 100,000 Chinese soldiers marched south by night, hiding during the day. Their singular objective was the complete annihilation of the 1stMarDiv.

The Thosaths’ 7th Marines led the march to Chosin. On Nov. 6, the regiment fought off a significant Chinese attempt to halt the column. The Marines sustained numerous casualties but ultimately beat them back. On Nov. 15, Marines reached the southern end of the reservoir at the town of Hagaru-ri.

As they prepared for the next phase of the battle, Bob penned another note to his parents explaining his Chosin experience. “I am still with the living and feeling fair,” he wrote. “As you probably know, we are still in combat. Haven’t frozen up yet … . We haven’t hit too much organized resistance the last couple days. The main trouble now is the cold weather. It has been 14 degrees below zero here a couple times with the darndest cold wind blowing. A lot of men have been turning in with frozen hands, feet and noses … . We got boots with three pair of socks. They help a lot. We have fur-lined parkas and two pairs of gloves. Our chow is always frozen solid so we have one hell of a time thawing it out.”

“We finally got the reservoir which was our objective,” he continued. “Our 1st Division got 4,000 replacements, so you can get an idea how many casualties we have had. I haven’t heard from Bill for two weeks, so I don’t know how he is. I wish I knew. I know his outfit was hit pretty hard.”

Bob closed the letter on a familiar note. “Give my love to everyone there. I love you very much Mom and Dad. I hope to see you soon. Well, I better close as I have a mission to fire. Goodbye for now. Your ever-loving son, Bob.” The tone of the letter must indicate that Bob, like his commanders, did not anticipate that the hardships they had encountered were nothing compared to what was to come. It must also suggest that despite his thankfulness for being alive, he would not consider that this letter might be his last.

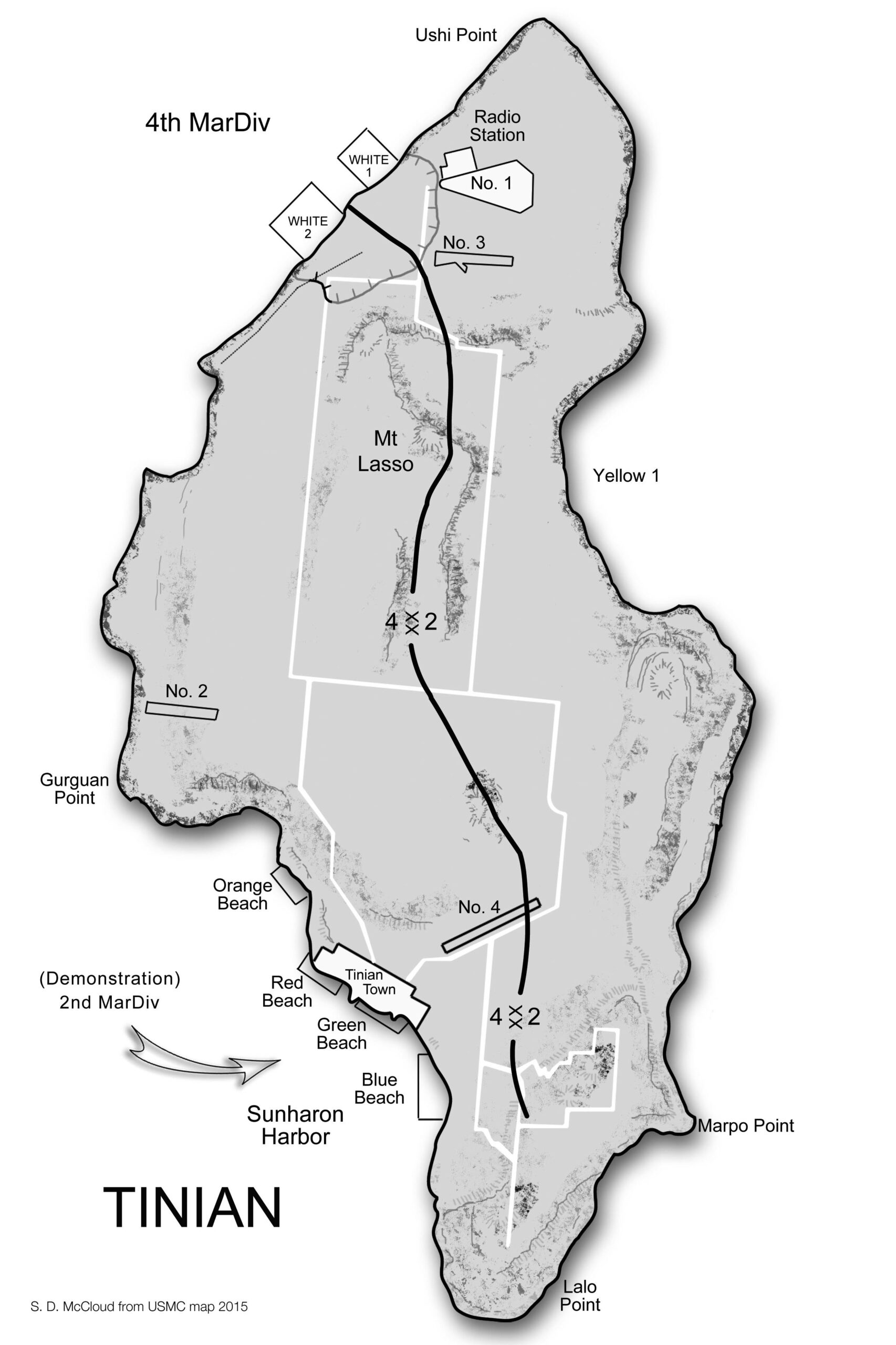

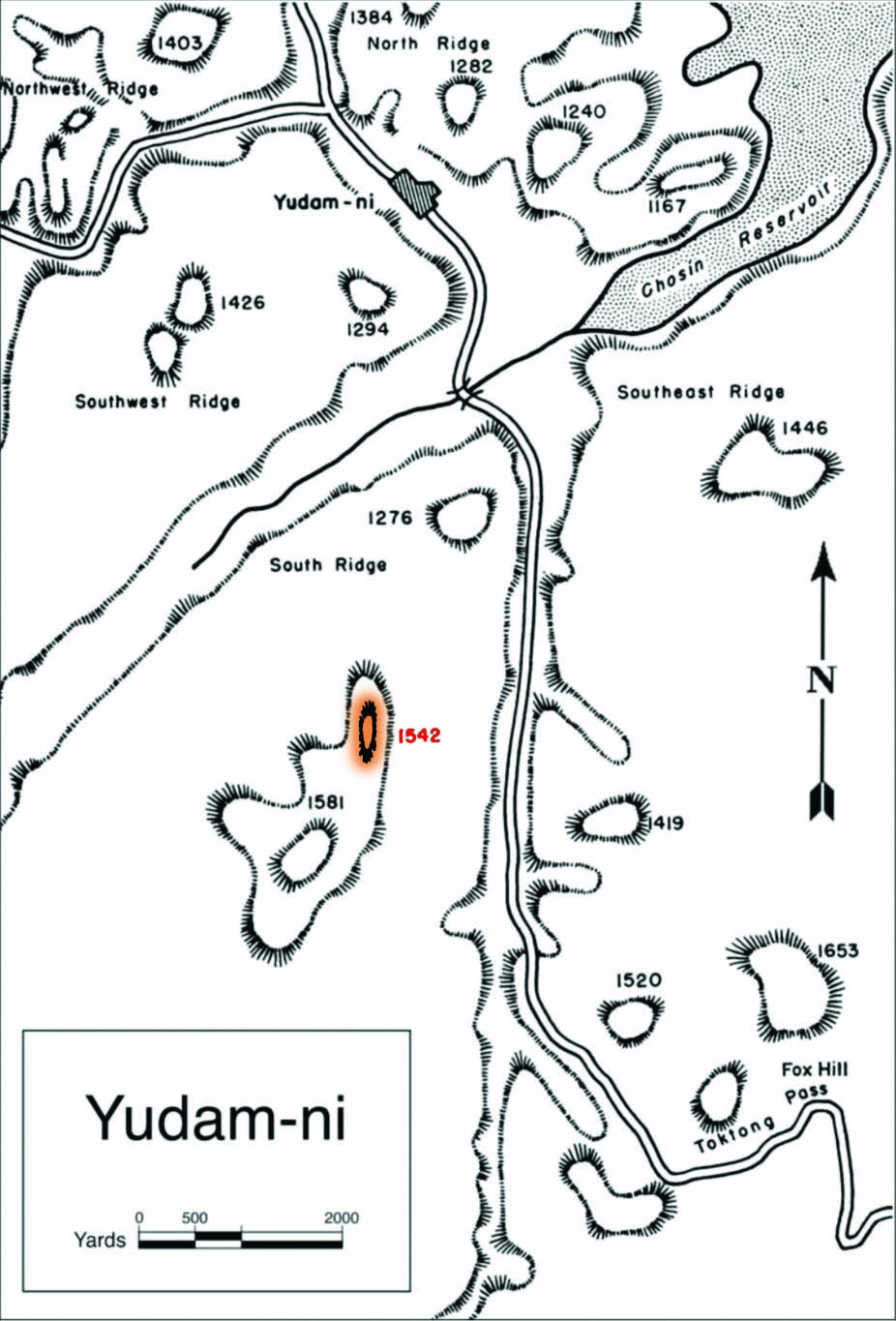

A few days later, the twins set out with the regiment again and occupied the town of Yudam-ni. They were further north and more isolated than any other unit of the Division. On the night of Nov. 27, the CCF finally revealed the full weight of their force. Tens of thousands of Chinese troops fell on the entire Division attacking points along the road, surrounding the Marines at Yudam-ni, and cutting them off from any reinforcements. The Marine aggressors quickly became the defenders as they fought to maintain a perimeter around the town. The isolated Marines beat back assault after assault from the enemy hoard. Air and artillery support provided the Marines’ only tactical advantage and played a key role in preventing a collapse in the line. Finally, three days later, commanders realized Yudam-ni could not be held and ordered the Marines to fight their way 17 miles back to Hagaru-ri.

For the defenders of Yudam-ni, their withdrawal would be like bursting through a closed door. The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines would burst through any enemy on the road south. The twins’ 3/7 would be the door. Their mission was to swing out into the hills and hold off the enemy as their comrades withdrew. Once Yudam-ni had been evacuated, 3/7 would move back to the road with the rest of the column as the last of the rear guard.

Bill’s George Co and Bob’s Item Co were assigned to the same objective—Hill 1542. They prepared to launch their attack on the morning of Dec. 1, six days before the twins’ 25th birthday. An enemy force more than twice their size occupied the high ground. As vulnerable as the attack would be, it had to be done. The withdrawing column on the road proved infinitely more vulnerable to the Chinese occupying the heights on both sides of the road.

The twins began their march up the slopes. The movement was arduous as they tried to gain a foothold on the hill. For six hours, the Marines fought inch by inch. The terrain advantage and superior numbers afforded the Chinese prevented the Marine attack from gaining momentum.

Initially, Bill’s George Co was held in reserve as Bob’s Item Co led the attack. By the afternoon, George Co entered the fray, along with headquarters troops, artillerymen and any other Marine available to swell the numbers on the hill. Night fell with the Marines locked on the eastern slopes of Hill 1542, looking up toward the endless number of enemy on the crest. Between Bob’s and Bill’s two companies, and the hodgepodge of others present, fewer than 200 Marines defended the position. Officers reorganized the men into a hastily formed defense. Bill took a position with the remainder of his platoon and prepared for the inevitable CCF attack. He looked to his left, where the remnants of Item Co held the flank of the Marine position. He couldn’t make out Bob in the dark, but somewhere down the line, less than 100 yards away, Bob set up his mortars and made sure his rifle was not frozen.

Chinese soldiers crept through the darkness down the hill toward the Marine line. Sporadic shots rang out as Marines saw movement in the shadows. Around 4:30 a.m., the sound of whistles pierced the air, and the Chinese onslaught came in full. Having located the end of the Marine line, the Chinese focused their attack on Item Co. Even as Bill fired his rifle and fought to hold his own, he looked in horror toward his brother’s position.

Squad- and platoon-sized elements of Chinese attacked points of the Marine line in sequence looking for a weakness. The Marines inflicted severe casualties on their attackers but struggled to maintain their position. Parts of the line were overrun and gave way. The Marines consolidated farther down the hill. The line formed once more, and again it faltered, giving more ground. By daybreak, the Marines had dealt enough damage to ward off the Chinese assault. Marines from all over Hill 1542 staggered back to consolidated positions near the road.

Bill searched for his brother. Having witnessed the carnage on Bob’s portion of the line, Bill felt encouraged to see any remnants of Item Co. But as he looked, a realization came that Bill did not want to acknowledge, a painful reality that he already knew to be true. Bob was dead.

Bill searched for his brother. They had always been together and if anyone could find him, Bill could.

None of the survivors knew anything about Bob’s location or what happened to him. Bill grabbed a fellow Marine and ran back up the hill. The Chinese still occupied the slopes, licking their wounds from the night’s battle. As the last Marines in Yudam-ni filed south down the road, Bill sneaked across the hill looking. He reached the area where the attack had begun the night before but could find no sign of his brother. Hiding from sight of the Chinese, Bill searched until the last possible moment. It was time for the rear guard to fall in. Bill departed Hill 1542 and marched south with the rest of the regiment. Always introverted with his feelings, Bill wrestled within himself as he marched, struggling to understand what had happened to his brother, how it happened, and what it meant. Bob would later be tallied as one of 33 Marines to go missing in action that night from the Division. This classification mattered little to Bill. He already knew Bob was gone forever.

For 10 more days, the Marines made their way south back toward the coast and safety. The going was maddeningly slow, with the column starting and stopping over and over. The battle-weary Marines literally slept where they fell. Under constant harassment from the enemy and unable to pause for a night of rest, Marines snatched minutes of sleep sitting, standing and walking. Their objectives of capturing the reservoir, driving the Koreans to the Yalu River and anything else they may have desired all fell by the wayside. Only one purpose now drove them forward—survival.

As the days passed, more and more Chinese prisoners of war were taken. It was discovered the enemy suffered equally, if not more, from the conditions and combat as the Marines. The Chinese force intent on destroying the Americans had suffered near destruction themselves in the effort. In this tragedy unfolding around the Chosin Reservoir, there would be no victors—only those who made it and those who did not.

The column finally reached the port city of Hungnam. Bill, along with the rest of 3/7 in the rear guard, were some of the last Marines to enter the safe harbor. Of the 25,000 Americans who began the march toward the reservoir weeks earlier, nearly 13,000 became casualties. Of those, 7,300 fell victim to the cold with frostbite, hypothermia or other non-battle related injuries. 200 Marines were missing in action.

They boarded ships and began the journey back around the Korean peninsula. Now out of danger, Bill took up the responsibility of writing his parents on Dec. 12.

“Hi you two, I know you are waiting for this letter, so I’m writing this one short,” he began. “I’m still alive and my health is still pretty good. We made it out of the traps, how I don’t know. It was more or less a living hell … . I have lost everything I had as our position was overrun by the [Chinese]. So now I am right back where I started but damn glad to be alive. Only God could have brought me or anyone else back, and I sure have been praying and thanking God for all that he has done for me. The outfit took quite a beating, and this idea of fighting both ways isn’t my idea of fun in case anyone asks.”

“They lost a lot of mail and packages which we were supposed to have gotten but rather than give them to the [Chinese] we burned them as the order of the day was just to take the beans and bullets, as we would be lucky to get out. So you see, I lost everything … .”

Curiously, the most bitter loss he suffered is the one ignored in his letter. Nowhere does Bill begin to address his brother or his loss. Bill’s reasoning for this is lost to history. Never one to address his feelings, it is possible the raw emotion was just too difficult to face. Still processing the events of the past days for himself, perhaps he simply could not find the words to express anything other than his own thankfulness for being alive.

How should one respond to such tragedy? In this intensely personal process, there can be no right or wrong answer. To suffer loss, violent and sudden, is a unique pain for which there is no road map of grief. For the families of those missing in action, the void of closure or assurance their loved one is even truly gone adds greater perplexity and weight to the burden.

The twins’ mother, Alice, refused to believe her Bob was lost. Within a matter of months, Alice had given birth to her fifth child, watched her boys return to war, and now was informed via telegram that one of them had vanished. It was more than she could bear. “She had quite a time mentally dealing with Bob’s death,” remembered Alice’s daughter Pat. “For about the first three years of my life I was actually taken care of by my brother James’ wife and my sister because my mother just was not able.” Alice began writing letters pleading for information. The War Department, the Red Cross, the Marine Corps, members of Congress and even the president, all received letters looking for information. She clung to the thought that Bob had survived.

Perry Thosath refused to speak of his lost son. In all the years following, until his death in 1979, Pat never heard her father speak of Bob, even during times where his alcoholism got the better of him.

Bob’s wife Jean was convinced that he had been taken prisoner. She wouldn’t accept that he had been killed. When Bill arrived back in the United States and was treated in a San Francisco hospital for his frostbite, Jean drove all the way to see him, convinced of the possibility that the twins’ identities had been mixed up and it was really Bob. She pored over photos of prisoners of war, looking for her husband’s face. In April 1951 she gave birth to a son, naming him Robert, after his father. Jean became extremely ill following Bob’s loss, and her doctors recommended a warmer climate. She packed 3-year-old Jackie, baby Robert and all her belongings into their car and drove to Fresno, Calif. She maintained little or no contact with the rest of the Thosath family. Even though she refused to discuss what happened with him, would later destroy all his letters, and eventually remarry, Jean always considered Bob the love of her life.

As others debated Bob’s fate and searched for information, ironically, one of the few people who could provide the details they sought had returned home to their front door. Bill arrived back in Washington in early 1951. After exiting the Marine Corps, he worked with his older brother, James, as a contractor and took a job as a pressman for the Spokane local newspaper. Much like his father, Bill would not discuss what had happened. It remained a place too painful to go. As his mother wrote her letters and hoped for a miracle, Bill would say, “You’re wasting your time. I was there. He could not have survived that.” This was as far as the conversation could go, and Bill was unwavering.

He threw himself into his work, occupying his time and his mind. Each Thanksgiving and Christmas, Alice planned family gatherings around Bill, tucking in meal times between his multiple jobs. Again like his father, Bill struggled with alcoholism, seeking a release from the burden he bore. Bill and his wife eventually adopted a daughter and tried to continue on along with the rest of the family.

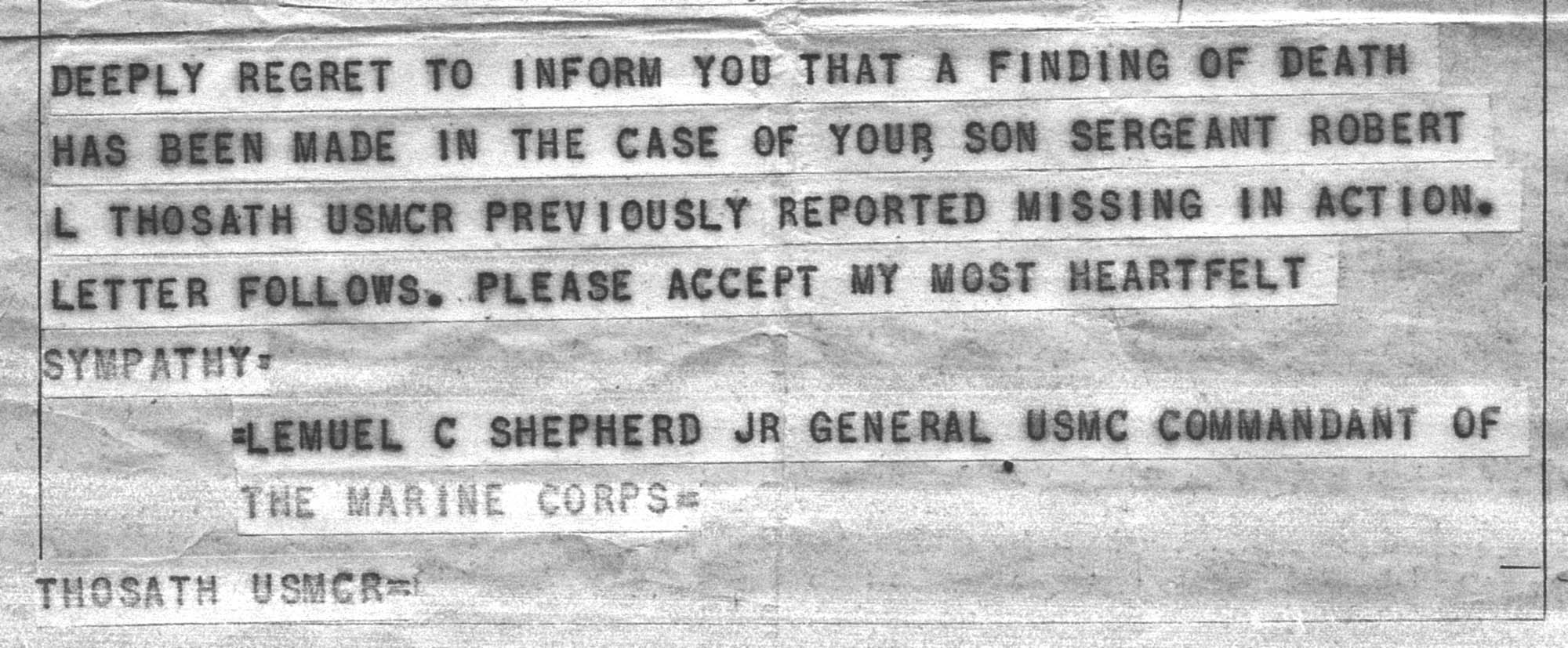

Three years after Bob’s loss, in December 1953, the Thosaths received another telegram in the mail. “Deeply regret to inform you that a finding of death has been made in the case of your son Sergeant Robert L. Thosath USMCR previously reported missing in action.” The military declared Bob dead due to lack of any evidence demonstrating otherwise. The official change in Bob’s classification had been made on Dec. 7, the twins’ 28th birthday. Until she died in 1987, Alice Thosath held out hope for her son. No funeral or memorial service for Bob has ever been held.

When Bob’s daughter Jackie turned 21, she decided it was time to meet the Thosath family again. She flew to Spokane for an anniversary celebration for her grandparents. “At first Bill didn’t come, he didn’t think he could see me,” remembered Jackie. “But he came during the middle of the party and he burst into tears. He burst into tears, then he took me on a tour of Spokane, and every place that he and my father loved to go. He showed me where my mom had lived and told me how Bob had met my mom. From then on, he and I stayed in touch.”

In 2001, Jackie attended a Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) Family Update in Los Angeles. These monthly meetings have been conducted since 1995 and are designed as a personal interaction between the families of MIA servicemembers and the U.S. government personnel whose mission it is to find them. The military personnel present wore dress uniforms and treated the families with the utmost respect. They gave presentations on the efforts going on across the globe and provided updates on servicemembers recently identified. Sitting across from Jackie and her son were the family of an American airman whose plane had been shot down during World War II. Her conversation with the other families, the amount of respect demonstrated toward them, and the realization of the worldwide effort going on to bring home the missing, all comforted Jackie. Seeing that there were others out there knowing, remembering, and searching provided her with some closure. When she returned home from the meeting, she called Bill to let him know she had attended and what was said. “Jackie,” Bill replied, “he’s never coming back.”

More than 7,700 U.S. servicemembers remain unaccounted for from the Korean War. Nearly 1,000 of those were lost during the Chosin Reservoir campaign. Today, the DPAA continues its operations to recover, identify and return the lost. More than 50 years passed before Americans were allowed to return to the Chosin Reservoir to search for remains. Since then, operations in North Korea have been alternately suspended and resumed as the hostilities between the U.S. and that nation ebb. As recently as March 2018, another American soldier, gone missing the same night as Bob Thosath on the opposite side of the reservoir, has been identified.

As Bill grew older, looking back on his life, his greatest source of pride remained his service as a United States Marine. “When he was very elderly, I would call him and when he answered, I would start singing the Marine Corps Hymn,” remembered his sister. “He’d just start laughing and tell his wife, ‘Oh it’s Patty again!’ I knew he loved to talk about the Corps, even though he didn’t go into his feelings, and that kind of became our thing. He knew he could talk to me, whereas some other people in the family felt that was a bad subject and didn’t want to go there.”

“I don’t know what the Marine Corps does to people,” Pat reflected. “They just get this thing where it’s a lifetime pride, and Bill was just so proud to have been part of it. And it speaks really well of the Marines for Bill to have gone through this experience, coupled with losing his brother, and when he’s 75 years old, he’s still so proud to be a Marine.”

Following his 80th birthday, Bill set out on his life’s final mission; reuniting with his brother. “I’ve had it in my mind that wherever he goes, I’m going to be there too,” Bill told a reporter for the local newspaper. With help from the local government, Bill worked it out with the Naval Mortuary Affairs Burial at Sea Program to have his remains brought back to Korea. They would return his ashes as close as they could get to Chosin. Bill died two years later, just shy of his 83rd birthday.

In June 2011, Pat opened a copy of the morning papers. A large, bold headline captured her gaze. “Decades later, servicemen’s remains returning to Spokane.” She read on to learn a U.S. Army soldier, gone missing in Korea, had finally been recovered and identified. His elated family was already planning the long overdue memorial service that could provide them some measure of peace. Pat closed the paper. Hope for her family seemed a forlorn reality, and there seemed no escape from reminders of the pain.

For the Thosath family, and all those families with loved ones still missing in action, peace remains incomplete and fleeting. “It’s not just our family,” said Pat “There are many stories, and because of what we’ve gone through, we understand it. Most people in this country, we love our soldiers.” She paused, struggling to subdue the emotion always accompanying memories of her brother. “So in a way, this is just another story about a soldier. But he was ours.”

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.