All Guns Blazin’: The Legend of Sgt Matthew Abbate

By: Kyle WattsPosted on September 15, 2025

Author’s note: By the time I left active duty in 2013, I knew the name “Abbate.” Sergeant Matthew Abbate posthumously received the Navy Cross in August of 2012, almost two years after his heroic actions while deployed with “Kilo” Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, in Sangin, Afghanistan. Abbate evolved into a living legend before he was killed in combat. His posthumous medal further propelled his stature within the history of his storied infantry battalion and cemented his place in the Marine Corps’ history of the war in Afghanistan. When I was asked to develop a story idea fitting under the umbrella of the global war on terror for Leatherneck, Abbate immediately stood out in my mind as a preeminent example from that generation; one of the best sons our nation had to offer. I knew the name and had read the Navy Cross citation but failed to grasp his importance to the Marines who served alongside him or the traits that made him purely “Abbate,” inevitably propelling him to the greatness he achieved and limited only by his untimely death.

Matthew Abbate deserves a place in our history, standing prominently alongside others such as Smedley, Chesty, Daly and Basilone. The Marines who knew him understand this best and can offer the rest of us a glimpse as to why. What follows may, hopefully, provide this insight. Thank you to Britt Sully and Jake Ruiz, both veteran Marine sergeants; Sergeant First Class John Browning, USA (Browning previously was a Marine sergeant); Gunnery Sergeant Chris Woidt, USMC (Ret); Staff Sergeant Ryan Salinas, USMC (Ret); Lieutenant Colonel Tom Schueman, USMC; and the other warriors interviewed for this story. Thank you for allowing me to laugh through the good times you shared with Matt and grieve with you through his death. If anyone can show us who Matt really was, it’s you guys.

The Boot

Britt Sully: Let me try to start at the beginning. When I graduated the school of infantry, all I wanted was to go Recon, but Recon was full, so they sent me to 3/5. I thought that was a death sentence. This was 2007. When I showed up, the battalion was still in Iraq, so we sat around for like a month waiting for them to get back. I viewed everyone around me as stupid and lazy; all these corporals serving as our temporary seniors that yelled at us and lightly hazed us. The battalion finally got back from Iraq. We unloaded all their seabags for them into their rooms and began our first experience dealing with salty lance corporals and drunk corporals fresh from deployment, further cementing for me, I have to get the f—k out of here.

A few days later, it was a Thursday evening, I was out in the barracks hallway cleaning the deck with a scuzz brush; just playing more stupid games for drunk 20-year-olds. While I’m outside cleaning the stairs, I see rounding around the corner of the barracks this 6-foot-2, handsome, square-jawed, tan-skinned man in boots and utes wearing a loaded Vietnam-era Alice pack. Long, glorious, thick black hair—WAY too long for a PFC to dream of having—and he’s running with a sledgehammer at break-neck speed. All these other Marines are standing around cheering him along as he’s just smiling and laughing holding up the sledgehammer above his head. I stopped cleaning and asked my senior, “Uh, Lance Corporal, who is that?” He snaps back, “That’s Matt Abbate and you don’t even f—king rate to look at him, now get back to cleaning!” Everyone else is just drinking and yelling at privates while this dude has a clearly heavy backpack and a sledgehammer and is sprinting towards First Sergeant’s Hill on a Thursday night. In that moment, I said to myself, “Whoever that guy is, whatever that guy is doing, wherever he is going, I want to follow him.”

At this point, Matt had been in for maybe two years. After he enlisted, he graduated boot camp as company honor man, making meritorious lance corporal, then finished the school of infantry as honor grad with a gung ho award. His character, demeanor and enthusiasm were just so genuine and magnetic that instructors were all talking about him, to the point that the Recon cadre got wind of who he was and poached him for Basic Recon Course. He goes to day one of MART, Marines Awaiting Recon Training, and is told to show up in green on green at 0530 for their initial PFT. He somehow f—ks it up and showed up in boots and utes. They were all told if they didn’t run a first class PFT, they would be immediately dropped. They tell Abbate, “You showed up in the wrong uniform, we don’t care. You still need to get a first class PFT.” Boom, Matt knocks out a 300 PFT in boots and utes. They made him run it a second time just to see if he could. Matt ran a second 300 PFT.

After a few weeks, while out on liberty, Matt met a girl from Tijuana and disappeared. He showed up after a week AWOL. At this point, usually if a guy shows up after a week, that’s like grounds for getting kicked out, but because he was impossible not to love, the instructors just NJP’d him, busted him down in rank and dropped him from the program. He showed back up to 3/5 as a PFC.

Ryan Salinas: Abbate wasn’t in my platoon initially, but everybody in Lima Company kinda knew that kid when he arrived as a boot. He was just super motivated, running around crazy. You tell him to go do something, it was like 100 miles per hour, no quit, no questions asked.

I first met him in Yuma at WTI while we were setting up cammie netting out at tent city. At one point, a group of us looked over and saw all these boots just standing around. We walk over there like, “What the f—k are you doing?” and we see one kid just getting after it by himself, swinging a sledgehammer and e-tool and whatever else he had. While the other guys started yelling at the other boots for letting this guy do all the work by himself, I went up to him and was like, “Hey, what the f—k are you doing?” He says, “Corporal, I’m gonna get this tent set up.” I told him he needed to get all these other guys just standing around to help him, and he just said, “I don’t got time for that bulls—t.” He kept working, meanwhile, it’s like 100 degrees, he’s pale white, and I noticed he had stopped sweating. I told him to go get some water, but he’s like, “No, no, I’m good.” Finally, I had to force him to go sit down in the shade. He was super upset he didn’t get the job finished. He wasn’t even in my platoon, I just saw it and was like, “What the hell is wrong with this kid?” So, I sat down and talked to him about understanding your limits and learning how to delegate within your peer group.

Chris Woidt: We came back from Iraq the first time in August of ’06. That’s when we got Matt in Lima Company. We knew then that we were already going back to Fallujah again. By that point, 3/5 had already done three previous OIF deployments. We still had guys around who were OIF 1 vets from ’03, OIF 2 vets from Operation Phantom Fury in ’04, then obviously all of us from the ’06 deployment, and we knew we were going back in ’07-’08. Initially, I was a squad leader and Matt was one of the junior Marines in the platoon. During our workup for the deployment, it became clear that Matt was pretty much a physical specimen. He always wanted more, which makes sense why he ended up coming into the sniper community.

Matt was a SAW gunner starting off. Prior to the deployment, we were at Twentynine Palms during the workup doing a shoot house with non-lethal Simunition rounds. With each scenario, they randomly changed the setup of the house. You’d bust into the room, and it may be full of enemy in an all-out gunfight, or it may be just a family. Your adrenaline is pumping, and it’s trying to teach escalation of force through these shoot, no shoot scenarios. Well, there was one scenario where there was just one woman sitting on a couch reading a book. She’s wearing a paintball mask and everything, and Abbate charges into the house blazing and just drills her like four times. Obviously, the instructors were like, “What are you doing?? She didn’t have a gun!” You could see Abbate was very self-critical, but he had a good sense of humor. During the debrief, when an instructor asked him why he “killed” a woman reading a book, Abbate held out both hands with palms up and smiled wide with those big, white teeth, and made a joke: “Because knowledge is power.”

Our deployment to Iraq was definitely kinetic, but there was a lot of political pressure to downplay the issues. There were numerous suicide bombers and casualties occurring around Fallujah, but the combat was waning. It was frustrating because there were a lot of handcuffs with the escalation of force and rules of engagement. Matt ended up getting meritoriously promoted to corporal during the deployment, so by the time we came back he was one of my peers.

After he was promoted, Matt was made a vehicle commander. We were primarily doing mounted patrols throughout the southern half of Fallujah. Matt would get really frustrated … from the mundane patrols and the lack of aggressive stance. That was just kind of a hard time too because the way we had fought the Iraq war and what had been drilled into his mind was now different. We were trying to do a lot more of civil affairs-type stuff. Matt had a lot of frustration because he wanted to do more. There were definitely times where we could have shot some people and done some stuff, but the reins were being pulled very hard because they were trying to bring down the number of firefights with the enemy to show a de-escalation in violence. We had pounded into his head and everyone else’s head the company’s experience in Fallujah over the previous deployments. We went back again very much with the expectation that we were going to take casualties. We were going to get in gunfights and kill people. But then we got there and transitioned from hot and heavy into more stability and security operations.

The Brotherhood

Chris: When we got back from Iraq, I don’t know if it was intentional, but they put all the 3/5 guys on the same street in base housing. All the Lima Company guys were neighbors living around a cul-de-sac. Matt was living in the barracks, but naturally whenever we’d do barbecues and hang out in the cul-de-sac, he would come over. One night I was in my house and I’m upstairs asleep. I heard noises downstairs, so I got up. I didn’t have a gun in base housing, so I grabbed a knife. I get down the stairs, and I can hear somebody right around the corner. I jump out ready to stab somebody, and there’s Matt standing in the kitchen with a bowl of Mac n cheese from the fridge, shoveling it into his mouth and laughing his ass off.

Matt was somebody who was welcoming, immediately part of your family, almost to his detriment. So many guys talk very highly of Matt because he died, but it almost doesn’t show his true personality. He was absolutely a flawed character, but his flaws really made us love him more. To the guys who really knew him, the tattoos, the long hair, the jokes, the bar fights, those were all part of the things that we loved about him. He had a really interesting childhood. We would really only get glimpses and pieces of it. There were definitely time periods where it wasn’t smooth. There were times he spoke about where he was sleeping on a beach in Hawaii where some other homeless dudes taught him how to catch eel and cook it over a fire. He worked as a waiter on a cruise ship one summer and had been to Thailand. He just had a big hunger to see the world, push the boundaries, and do big things, so coming into the Marine Corps made perfect sense, especially with the wars going on. Matt was the quintessential “break glass in case of war” type Marine. He joined for that, and that’s what he wanted to do.

Ryan: While we were in Iraq, we had a buddy who had a Harley back in the States and he got me and Matt interested. We started doing a bunch of research, looking up different bikes whenever we could get internet. As soon as we got back to California, the first thing we did was buy bikes, and all we did was ride.

We were in my garage at my house in the cul de sac one day and he brought his bike over. We were changing the oil or whatever on my bike and he decided to do some work on his bike too. Well, there’s this metal derby cover over the clutch that he decided to pull off. I walk inside the house to grab some drinks for us and as I’m walking back around the side of the house, all of the sudden, I see this shiny metal disk go skipping down the driveway and stick in the grass in the neighbor’s yard across the street. I ran into the garage … he’s like, “Go look at that f—king derby cover!” So, I go grab it and I’m like, “Well yeah, it’s all scratched now.” He’s like, “No, turn it over bro.” So I turn it over and it says, “Made in China.” I look at Matt and he yells, “How the f—k are you gonna have a Harley and it says made in … f—king China?! Get in the truck! We’re going to buy an American-made … derby cover!” We drove all over southern California to every damn bike shop just to find one … derby cover that was made in the U.S.A. so he could put it on his bike. I mean, he was absolutely pissed off that this thing was made in China. He was just like the patriotic, steak-eating, red-blooded American. I can still see his face right now the way he looked at me when he found that out.

The Beast

Britt: My first experience personally meeting Matt was a few days after I saw him running out of the barracks. I was a PFC, he was a corporal. As a young PFC, speaking to a corporal meant like parade rest, don’t look him in the eyes, especially in the infantry. I did not expect to be spoken to like a human by anyone who had been in the Marine Corps more than 40 seconds longer than I had. I met Matt on the basketball courts with our gear list to begin sniper indoc. Matt was just like, “What’s up, bro? Are you excited? You ready to do this?” I was just speechless, like, “Uh, why don’t you hate me?” He just gave me a slap on the shoulder and said, “Let’s f—king go!” He was always in front of the rest of the pack, finishing everything ahead of everyone else, then looping back to make sure the last guy made it in.

Jake Ruiz: I met Matt during scout sniper indoc. I was a junior Marine. They actually gave Matt time away from squad leader’s course to do the indoc. My first impression was just how much of a beast he was. He was just destroying all of us on the physical events. I was like, “Who is this guy?” I didn’t really get to know him until a couple weeks later when me, Britt and Matt all joined the sniper platoon working up for the MEU, but we all got close quickly. He graduated honor grad from squad leader’s course, even though he missed part of it for the sniper indoc. His ability to learn military skills in general was second to none. That’s one thing that gets lost in all the stories about Matt. Everyone talks about how much of a beast he was. I mean the dude was huge. 6 foot 2, 220 pounds, strong as an ox; everyone talks about that, but they don’t talk about how smart he was. His intelligence related to military skills blew me away.

Matt started getting tattoos while we were gone on the MEU, and he didn’t stop until we left for Afghanistan. So, over the course of maybe a year and a half, he got two full sleeves. At the time, it was that weird policy on tattoos; couldn’t be visible or had to be spaced a certain way or whatever, but Matt never really got in trouble for anything. He was just untouchable. Everybody in the battalion knew who Abbate was, from the sergeant major down to every PFC. Over the course of the MEU, everybody in the MEU knew who he was. He was that guy who would talk to you once and you’d think, “Man, this guy is my best friend!” Matt liked his hair, he liked his tattoos, he was high risk on libo, but that’s just part of what you get when you have a man like Matt. You’re not gonna get one without the other.

While we were gone, Matt tried to lateral move back to Recon, but something kept getting messed up with his package and it never worked out. We were all pretty downtrodden being on the MEU. Everybody just wanted to go combat. We got back in September 2009. Right before Christmas leave, we found out 3/5 was going to Afghanistan. Matt could not have moved faster to get the paperwork done and reenlist. I had to extend my contract to stay with the battalion for the deployment. We were all like, “OK, send us to sniper school and let’s get this done.” We deployed on the MEU with the sniper platoon, but we were not yet school trained. I lucked out, and I got to go with Matt.

While we were getting ready to go to sniper school, Matt pushed us super hard everywhere we went. He had to work out every day, it didn’t matter what we did that day. We’re doing all this deployment workup training during the day, then we get back to the barracks and Matt is dragging me out of my bunk to the pull-up bar and dragging his 53-pound kettlebell with him. We’d be driving all over base getting our medical paperwork or whatever else all signed off so we could go to sniper school, he’d see a pull-up bar and make me pull over. Looking back, that’s just how he was, who he was. He never missed an opportunity to make himself better. By the time we went to sniper school, I knew Matt really well; I knew what kind of performer he was. But under the microscope in a school like that, he elevated his already high performance and outshone everybody. It was wild watching him perform at that level. He finished sniper school number one in every skill except for stalking. Stalking is extremely hard. It’s a very, very patient skill, and Matt was terrible at it. It was his kryptonite.

Britt: During our workup for Afghanistan, Matt was given meritorious sergeant. In the sniper platoon, he only wanted to be called Matt, he never wanted to be called sergeant, because he truly believed that you didn’t follow people because of their rank. You follow people because you trust their decision making, maturity, experience and character. He went to scout sniper team leader’s course, finishing high shooter and honor grad. He eventually became our team leader, working with John Browning, our assistant team leader, in charge of the 10 snipers of “Banshee Three” attached to Kilo Company.

The Artist

John Browning: I had done three previous deployments, two in Iraq, but 2010 was my first time in Afghanistan. Iraqi insurgents were more just thugs with guns; they were pretty easy to dominate, at least around Ramadi and Habbaniyah where I was. The Taliban were much better fighters, much more dangerous. They were there to fight. They did a lot of support by fire with machine guns, just like we do. As the sniper team, we took advantage of that. We’d hunt in places where we thought they might set up; opportunistic-type stuff. An infantry squad would go out on a pre-planned patrol route, and we’d have already been there all night. When the Taliban engaged the squad, we were there to shoot them.

Chris: When Matt got to Afghanistan, he finally had gotten into the free-fire zone of a highly kinetic area. Sangin was the canvas, and he was the artist. We knew him as a junior Marine, up and coming, but making dumb boot mistakes and those kinds of things. By the time he made it to Afghanistan—a sergeant, a sniper team leader, on his third deployment—he was highly developed. He’d mastered the art.

Jake: Our sniper team arrived to Afghanistan at the end of September 2010. We were forward staged in Sangin, operating out of Patrol Base Fires. Matt and John got there before the rest of us and were doing left-seat-right-seat patrols with the sniper team we were relieving. They got into a TIC [Troops in Contact] and killed some guys before we even got there. From that point forward, Matt was absolutely relentless. He wanted to do nothing but go out, find Taliban and shoot them. Once we all got there and started operating, he was personally going out two or three times a day, to the point where John would have to be like, “Dude, you need to take a break.” Matt just didn’t want to ever slow down. It was almost like he took it as a personal challenge that he had to keep people safe. It’s like he just knew that he was better that anybody else and he needed to be out there.

At that point in the deployment, we were extremely active. We were going out, either on our own as snipers or in small teams with the squads, two or three times a day. It was just so much combat. Those first couple months, it felt like you didn’t go outside the wire without getting into a firefight or somebody hitting an IED, or both. The days really ran together. It just felt like one continuous firefight and mass casualty incident.

Very early on, Matt wanted to go out super early one day. He got us all up probably 3 or 4 in the morning, we do our pre-combat checks and leave the wire under night vision. Matt wanted to set up near an area where the squads had been getting hit from when they left the patrol base. We made it a couple hundred meters outside the wire. Matt was running point behind the engineer with the metal detector. We hit an IED, but it low-order detonated, so a small portion of the homemade explosives inside detonates, but most if it just kind of gets thrown out. I was four or five people behind Matt. When we hit this thing, it scared the s—t out of me. I thought Matt was gone, thought the engineer was gone; what the hell are we going to do now? All the sudden, I just see Matt pop up and ask if everybody was alright. We made our way back to the patrol base, and I was just terrified. We get back and realize that Matt and the engineer are coated head to toe in the explosive material. They looked like they were covered in glitter from the aluminum powder in the explosives.

Britt: Matt just laughed it off and told us it looked like he was at a rave. He went right back out on patrol when the sun came up.

Jake: Later that day, the EOD techs went out to investigate and dismantle the IED. Well, they found it was a daisy-chained IED, and the secondary explosive on the daisy chain was so big that, had it gone off, it would have killed our entire team. I want to say that was unique, but it wasn’t for Sangin. It was just like that everywhere; the IEDs and the level of danger. To be honest, it was scary realizing how vulnerable we really were and how little we could mitigate that. I remember telling Matt, “Dude, I don’t know how are we gonna do this?” He was just like, “Bro, it’s our job.” That’s when it really clicked for me that Matt was just a different breed.

Britt: Matt was always so willing to go out where there was 100% probability there was going to be a gunfight. He would put himself there, and he would aggressively maneuver. He got his first patrol and first kill in before the rest of us touched down. For most people, when there’s machine guns and rockets going off, it’s intuitive to seek cover. But Abbate would just maneuver. He’d trudge off through the mud with his tree trunk quads in the direction of where he thought he could smoke people, like a Belgian Malinois unaware of what bullets are. Honestly, Matt doing something like action-movie heroic was just a day-to-day occurrence. When we heard about what he did on Oct. 14, it was really just more of Matt continually doing his thing; more of Matt just being Matt. To us, the real significance of that day was that we took a lot of casualties.

The Hero

Jake: On the morning of Oct. 14, 2010, we had gone out and done our own thing, and the patrol had been uneventful. We were just kind of kicked back relaxing when we heard a firefight start, and it sounded pretty heavy. After a while without breaking contact, the squad requested QRF. Matt jumped up and threw his gear on and was like, “Come on, let’s go!” So, four of us kitted up and jumped in with a squad getting ready to push outside the wire. The idea was that we were going to set up a blocking position and either draw the contact away from the other squad or at least provide them some covering fire as they withdrew back to the patrol base. At some point, the Taliban realized we were out there and broke contact, so the other squad was able to start making their way back to the base. The squad leader we were with decided to head back as well.

There was a huge open farming field that we bounded across from one irrigation canal to another on the opposite side. Generally, in recently planted fields like that we weren’t too worried about IEDs, so me and another guy just sprinted across and got to the canal. Some of the Marines in the squad made it right after us, and the SAW gunner immediately detonated an IED along the canal. I was probably 15 feet away and my bell was rung. After that, all hell broke loose. It felt like the sky opened up, and we were under fire. By that point, then entire squad was moving. The squad leader got shot in the leg as he reached the canal and fell down right next to me. A bunch of the rest of the guys tried to take shelter in this mud hut that was just to our left. We knew better, but that machine-gun fire was just so intense that I think it just pushed them in there, like an involuntary reaction to seek cover. They moved in, and one of the guys immediately hits an IED inside. The corpsman from the squad knew the Marine was down inside the compound, so he went inside and stepped on another IED. All the while, we’re taking heavy machine-gun fire.

By this time, Matt was in the canal with me. I was trying to pull the SAW gunner out of the water. I was so disoriented. One of the guys helped me get him up on the bank and that’s when I realized that he was gone. I assessed the squad leader and was trying to get a tourniquet on his leg. Meanwhile, Matt is realizing, “Oh s—t, I’m it. I’m the only one here who can do this.”

Matt jumped up with the minesweeper and made his way into the mud hut. Funny thing is, Matt didn’t even know how to use the thing. So, looking back, you realize he was just doing that to make other people feel better. In reality, he was clearing that compound with his feet. He cleared it and one of the other snipers started treating the casualties inside.

I was on the radio calling for a medevac. The whole time, Matt was super composed, getting people on task. Calm is contagious, and that is what he was; he was the calm. We finally started to make some headway, and the machine-gun fire died off a little bit. I was shook up. This was the first mass casualty I’ve been in. The first dead Marine I’ve dealt with. It was pretty overwhelming. Had Matt not been Matt, I don’t know that I would have composed myself.

Author’s note: According to other sources and eyewitness accounts of Abbate’s actions on Oct. 14, Abbate ordered the remaining Marines to freeze following the three IED blasts that decimated the patrol. Ignoring his own order, Abbate swept the ground for IEDs all the way to the structure where multiple bombs already exploded, then arranged the remaining Marines in a defensive posture. When the sounds of medevac choppers echoed overhead, Taliban fighters resumed machine-gun fire from the opposite side of the open field that would serve as the landing zone. Abbate charged across the open, unswept field, initially on his own, driving the Taliban away in a hail of gunfire. He then single-handedly swept the entire landing zone with his feet for IEDs to ensure it was safe for the helicopters to land.

Jake: We got told the Brits were coming in for medevac, so I popped smoke to mark our location. The bird came in out of nowhere, flying low to avoid RPGs. It circled the LZ then hit the deck so hard I could feel it through the ground. Some dudes ran out the back with guns and started laying down rounds, while some others ran out with stretchers. I was trying to get the SAW gunner to the bank of the canal and onto a stretcher. He was bigger than me, and I was just struggling. I grabbed … his hand to pull him up, and I felt his hand come apart inside his glove. It was the most surreal thing, and I just froze, standing there in the open. Matt came up and put his hand on my shoulder and just said, “I got this.” And he did it. He got the kid up on the stretcher.

The bird lifted off with the casualties, and we bounded back all the way until we made it inside the wire. All of us were absolutely smoked; just that huge adrenaline dump and a rush of emotion. I was crying. Matt came up and put his arm around me and said, “You feel that?” I said, “Yeah, yeah I feel that.” He said, “That’s why we’re gonna kill more.” That was his mentality. He wasn’t going to let them get away with hurting the Marines. Within the hour, I went back to hooch, and I fell asleep. It was early, probably like 5 or 6 in the afternoon. I didn’t wake up until like 9 the next morning. Matt was already back out on another patrol. He let me and the other snipers sleep. It was just his way of looking out for us. He knew we needed a break, but he wasn’t going to take a break.

The Symbol

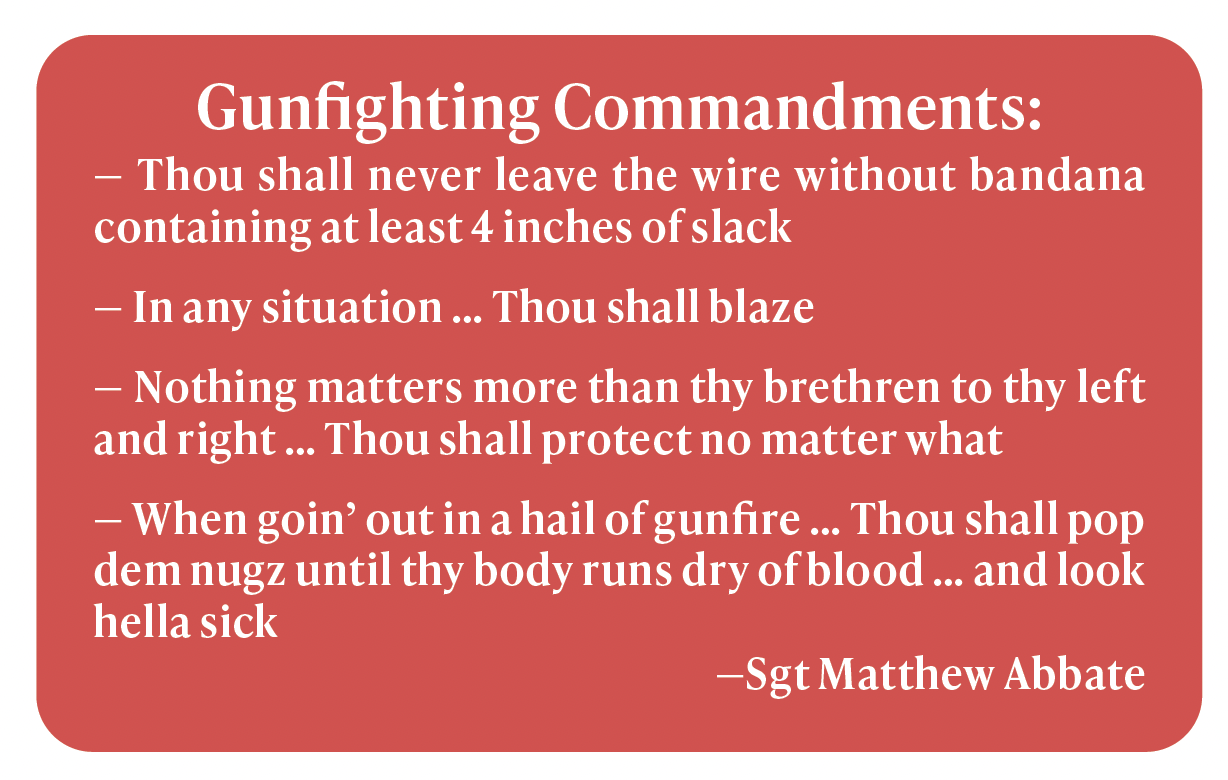

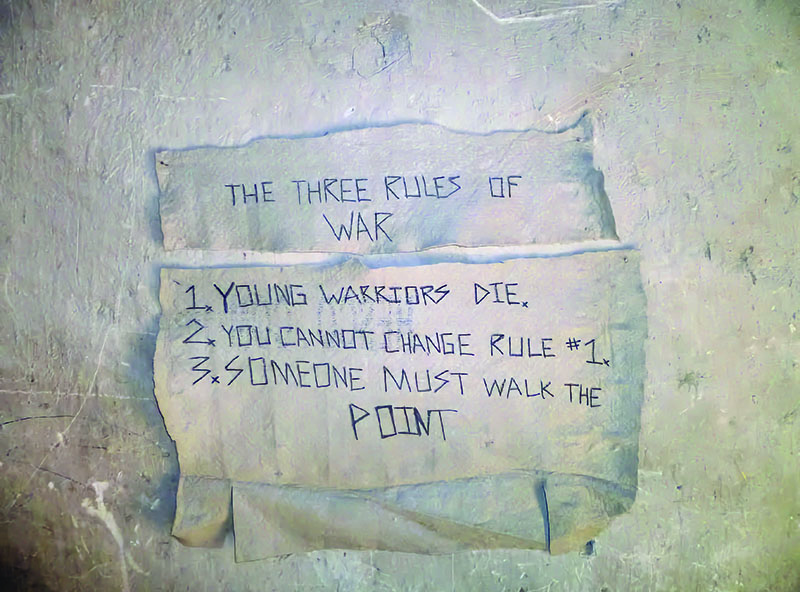

Jake: Throughout the deployment, Matt was really big on symbols. We had a wall where we carved stick figures for all the enemy we killed or even buildings we destroyed in air strikes. Matt encouraged it because he wanted people to know what we were doing. He wanted us to know that we were making a difference, and whenever we would leave, he wanted them to know that we made a difference. The gunfighting commandments and rules of war were his own creation. To me, they were reflective of his personality.

Matt was a really over the top guy. His favorite movies were ’80s and ’90s action flicks. He just thought they were awesome. When he showed us the gunfighting commandments, he thought it was hilarious, but he also thought it was badass. I think for Matt it was a way to make light but also be serious.

John: Matt came up with this thing called, “slack” in his bandana. Matt loved bandanas. His first gunfighting commandment was, “Thou shall never leave the wire without a bandana containing at least 4 inches of slack.” He’d always say it in his surfer voice, and it was funny as hell. The slack was the loose ends of the bandana dangling like a ponytail. We’d be getting ready to go out and he’d be like, “Ok everybody, get your slack” as he’s tying on a bandana before he put his helmet on. I still do it to this day when I ride my motorcycle.

Britt: The gunfighting commandments were just Matt’s mentality towards wearing the uniform that were unspoken but lived. Not necessarily the words themselves, but the attitude he took towards everything. He so much loved wearing camouflage, sweating and carrying guns with the potential of blasting holes in people, and he lived that. He could have written the gunfighting commandments a million different ways, but it all would have said the same thing; look cool, feel cool, protect your homies and kill the people trying to kill you. In the least eloquent way, that’s just who he was.

Jake: His rules of war I think were based off something he read in a book, but he put his own spin on it, but it hit home for all of us. Someone’s got to walk point, that was just reality, and some of us weren’t going to go home. I think what separated Matt from the rest of us was that he had already accepted that before we even got there. John, too, already knew. He had significant combat experience and was blown up by an IED in Iraq. He knew the consequences of what we were going to deal with and was OK with it. I guess the wild part for Matt is that he was prepared for the reality but had not yet experienced anything like it. By the time we left Afghanistan, we all could go out, and we knew what we were looking for, we knew what the contact would be like, we knew we could step on an IED, but that fear was kind of gone. Matt was like that from day one. I think his gunfighting commandments and rules of war were just helping the rest of us get accommodated.

The One in Ten Million

Britt: On Dec. 2, 2010, me and Jake had just come back from a two-man sniper operation. We went out at dawn and came back four or five hours later with nothing really happening. I’d been back inside the wire for maybe 30 minutes cleaning my gear and refilling my water. We heard a gunfight start up in the distance. We heard the radio traffic, and it sounded like Matt and the rest of the guys out there totally had the initiative, but I geared back up just in case they needed a QRF. The guys saw some Taliban go inside a building. On the radio, we heard jets get called in for air support. We watched both birds go overhead, and we watched both bombs drop. We had made a habit of calling in the first bird to drop a short delay 500-pound bomb so that it would penetrate inside the building and blow it up. The second bird would follow up with an air burst above the same target to kill anyone who survived the first drop and was trying to flee.

Maybe 30 seconds after the second bomb dropped, we hear that there is an urgent surgical wounded. Abbate threw his gun back up on the berm and started scanning for somebody to shoot after the first bomb. Just the geometry of chance unluckily caught him in the neck with a piece of metal from the second bomb. We didn’t know that then, we just heard Abbate’s kill number come across the radio. But, Abbate was larger than life. I’m thinking, “Matt will be fine. He’s Abbate. Nothing can touch him.”

Jake: Within a few minutes of the medevac bird taking off, we all received notification that we were “River City,” which means that we’ve got somebody dead and all communications with home were cut off to prevent anyone from communicating with the Marine’s family. My heart sank; just gut wrenching. I was trying to reach our Kilo Company HQ to confirm what we just heard, because I just couldn’t believe it. I ran up to the patrol base’s comm shack and got on the radio. I said, “Kilo main, this is Banshee, confirm your last traffic.” Our forward air controller, a great guy, came back and was just like, “I’m so sorry, Banshee.”

Britt: It felt totally unreal to all of us. Everyone felt very mortal in Sangin, but nobody thought you could touch Matt. He was invincible. We all just felt like, “If Abbate can get killed out here, there is no way I’m going to survive this.” His death reverberated through the entire battalion.

Author’s Note: 3/5 remained in Sangin until April 2011. The battalion suffered 25 killed in action and more than 200 wounded. Throughout the entire 20-year war in Afghanistan, 3/5 suffered the worst casualty rate of any Marine battalion.

Jake: Our deployment to Sangin 100% shaped everything about the remainder of my time in the Marine Corps and still does to this day. Matt’s relentless nature in everything he did, his relentless strife to be the best and outperform his best pushed me to be a better performer and made me push my Marines to outperform their best. Matt never had an ounce of quit and never left anything on the table. As a Marine, you can’t have any quit because, ultimately, no matter what you do, the enemy always has a vote.

Britt: Be as excited and proud to wear the uniform and do the job that you were the day you went to MEPS. When you didn’t know any better, when you didn’t know how stupid the games could be, when you didn’t know how lame the regulations are, and all the things it takes to get to wear the uniform and do the job; just show up every day excited to wear that uniform. Matt was just excited to get to be a Marine. To take off his uniform drenched in sweat and dirt, sore from trudging up hills carrying a machine gun. That was a good day to Matt.

It’s tough to call him anything close to an example of a window into what the Marine Corps was like during our era because Abbate was truly one in 10 million. I don’t know how many Marines served in the GWOT, but in that 20 years, there are only a few other dudes that had the impact on the people around him and the larger-than-life impact in the day to day. His exemplary character, attitude and performance in everything he did had so much gravity. Everyone who served with him on a day-to-day basis knew this guy was what you think of when you think ‘real Marine.’ When I say ‘real Marine,’ I don’t mean textbook recruiting poster, handsome, barrel-chested, shaved face dude. I mean absolute f—king killer, that’s a libo risk, that takes care of his dudes and leads from the front.

Jake: Matt taught me that you have to love your subordinates, whether you like them or not. He took every opportunity to train hard. He was the epitome of a Marine. He set the standard that I strive to reach, both through my time in the Marines and my current career in law enforcement. The lessons that I learned by watching Matt have shaped my entire adult life. I count myself very fortunate to have known him.

Author’s note: Matt Abbate was 26 years old at the time of his death. He is survived by his wife, Stacie Rigall, his son, Carson Abbate, his mother, father and three siblings.

Featured Image (Top of page): Sniper Team “Banshee Three” at Patrol Base Fires, Sangin, Afghanistan, during their 2010 deployment with 3rd Bn, 5th Marines. Sgt Matthew Abbate, wearing a tan bandana, is holding the left side of the flag. Abbate’s story was shared with Leatherneck by several Marines including Sgt Britt Sully, standing far left, Sgt Jake Ruiz, holding the right side of the flag, and then-Sgt John Browning, kneeling, front right. Etched into the wall behind them is the sniper team’s running tally of confirmed kills during their deployment.

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the winner of the Robert Debs Heinl Jr. award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond with his wife and three children.