Aboard Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, Calif., one training company is tasked with producing a coveted and demanding Marine specialty—elite among the elite.

Reconnaissance Training Company (RTC), nestled within the School of Infantry-West, holds sole responsibility for transforming Marines into 0321 Reconnaissance Marines. Prospective candidates endure a rigorous training pipeline. They must volunteer for a shot at the advanced qualification, and RTC representatives extend the opportunity to Marines of nearly every Military Occupational Specialty (MOS).

Following completion of basic combat training, volunteers enter an additional 18 weeks of training and assessment. The Recon Training Assessment Program is a grueling five weeks, pushing Marines to the limit and screening out any who will not make the cut. The Basic Reconnaissance Course (BRC) follows. In 13 weeks, the same amount of time spent in Boot Camp, RTC staff completes the transformation.

From the moment they step on the yellow footprints at Parris Island or San Diego, to graduation day at BRC, Recon Marines endure nearly 40 weeks of continuous training to earn their MOS. BRC graduates have only just begun their journey, however, and remain unqualified to enter the Fleet Marine Forces. An additional six months of training must be completed. All 0321s earn their jump wings at Basic Airborne Course and Multi-Mission Parachute Course, their dive qualification at Marine Combatant Diver Course, and pass through two weeks of hell at Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) School. Only then is a newly minted Recon Marine fully qualified for assignment to a fleet Reconnaissance Battalion.

The advanced training and stringent requirements exist as a result of the community’s experience in combat and their mission as the Marine Corps special operations-capable force. The activation of Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC) came about largely through the reassignment of Force Recon or Recon Battalion Marines to the MARSOC pilot program known as “Det One” in 2003. Again, several years later, 1st and 2nd Force Recon Companies saw wholesale deactivation and redesignation to create the genesis of the Marine Special Operations Battalions. Today, Marine Raiders exist as an elite force of warriors operating under the purview of U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM). They are, in effect, Special Operations forces who happen to be Marines. Recon Battalions exist within the USMC chain of command, operating at the will of forward deployed commanders.

Recon Marines have always been, and remain today, the special operations-capable force of the Marine Corps. The community traces its lineage back to the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion of World War II. The Vietnam War, brought about the most significant evolution in Recon doctrine and cemented their role in the Corps’ mission. It’s been 50 years since Recon procedures and tactics were written, but the lessons learned remain critical today. Despite the advent of new technologies, weapons and entirely new battle spaces, the key attributes that define a Recon Marine or corpsman remain unchanged and are amplified as the Recon community looks toward the future.

The Corps began a dramatic reshaping and reorganization several years ago under Force Design 2030 (FD2030). The advance technologies and new adversaries shaping tomorrow’s war initiated changes felt across the fleet, affecting each Marine, down to the individual rifleman. While many MOSs now look significantly different, or even simply no longer exist, the Reconnaissance community discovered in its future a return to its roots established in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Retired Force Recon Marine Jose “Pep” Tablada III, currently serves in a crucial role to the advancement of FD2030. Tablada spent 13 years as a Force Recon Marine, deploying in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and being named the Force Recon Team Leader of the Year twice before his medical retirement in 2005. Since then, Tablada has held a series of civilian roles within Marine Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC), presently working as the deputy assistant chief of staff for Operations of all Marine Corps forces in the Indo-Pacific region. He was part of a team hand-picked by General David H. Berger, the 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps, tasked with devising the strategies for future warfare and working with I and III Marine Expeditionary Forces to implement force modernization and forward posturing in the Pacific.

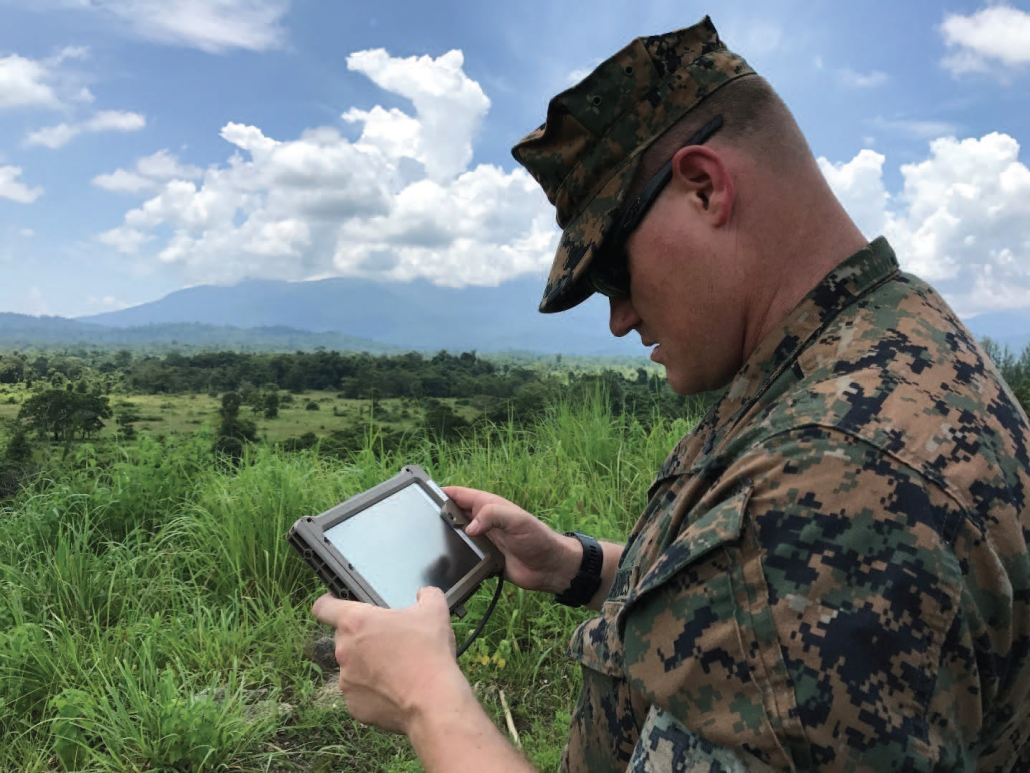

“Recon Marines primarily focus on deep reconnaissance, battle space shaping, and direct action precision raids,” Tablada explained. “In the traditional sense, much of the deep recon and battle space shaping missions remain the same as in Vietnam. What is very different is the fight we are in today is much, much more advanced. You’ll hear detachments getting deployed today being called, ‘All-Domain Reconnaissance,’ and the reason why that’s different is because Marines and Sailors today have the technology and training to bring cyber, signals intelligence, and space capabilities to the fight. It’s amazing what today’s Reconnaissance Marines can do.”

Detachments from Recon Battalions deploy with each Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), as well as in support of numerous other specified tasks around the world. While the naming of these detachments varies depending on the parent command of the MEU, the function is identical. A host of “enablers” deploy alongside them, such as cyber or signals intel-trained Marines, allowing this special-purpose force to conduct a wide variety of missions. The detachments train for maritime-specific direct action raids, such as gas and oil platform seizure and “Visit, Board, Search, and Seizure” (VBSS) to support interdiction operations of a naval vessel. Technologies such as satellites and drones assist them in locating the enemy, understanding what they are doing, and directing other friendly forces within the battle space. The ideas surrounding deep reconnaissance in a future war present a different set of challenges.

“The next war in the Pacific will look different from anything we experienced in the Global War on Terror,” Tablada said. “Small units will be dispersed across a large area. They will have to be independent in austere environments, on their own for long periods of time, and possessing their own means of mobility. There will be limited or no resupply, and no Forward Operating Base to return to in many instances. Imagine a Recon detachment having its own long-range maneuver platform, like a modernized PT boat from WW II. They go out in the waterways and the littorals of the Western Pacific searching for maritime targets. They’re going to use their all-domain capabilities to find those targets, fix those targets, create targeting data, then hand it off to the bomber or the submarine or the cyber strike to destroy it. This doctrine is new in terms of the expansiveness of what will be expected from a Recon detachment. They will have to operate truly independently of the commander’s intent. Not only will they have to complete the mission, but they will have to figure out how to sustain themselves for longer periods. They will have to be smart, resilient, and professionally aggressive with a mature sense of tactical judgement.”

As new doctrines progressed, Colonel Robert J. Coates, USMC (Ret), recognized a potential area for improvement in the Recon training pipeline. During more than 32 years on active duty, Coates served as the officer in charge of the Amphibious Reconnaissance School, commanding officer of 1st Force Reconnaissance Company, and later as CO of the MARSOC pilot program, “Det One.” In 2016, Coates was inducted into the USSOCOM Commando Hall of Honor. He is one of only nine Marine inductees since it was established in 2010. Other inductees include well-known Marines: Evans Carlson, James Capers and John Ripley.

Now in retirement, Coates continues serving the Marine Corps as a mentor to deploying MEUs and Special Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Forces, including their respective Recon Battalion detachments. He understood the role of deep reconnaissance was not going away, and the only place in history to find the experience was Vietnam. Throughout the Global War on Terror, the mission set dealt to Recon focused heavily on direct action raids against insurgent leadership. They simply did not operate within the battle space in the same way Marines did during Vietnam, nor will they be expected to in the future.

Coates remembered his own Recon instructors as a young Marine growing up, veterans of the early 1960s and 70s, immensely proud of their service. They exacted standards of perfection in appearance, discipline and physical fitness. Even years later when he was a colonel in charge of 1st Force Recon, Vietnam veterans continually impressed him by visiting the company offices and attending company functions in order to remain connected to the community and support active-duty Marines. Being a Marine remained the most defining and profound experience of their lives, and despite the decades passed, they continued to unselfishly give back to the Corps. As Coates considered the details of creating a professional military education (PME) on Vietnam-era reconnaissance, and who to lead it, he requested help from a personal friend and mentor: legendary Recon Marine, Sergeant Robert Buda.

Buda’s name is no stranger to Leatherneck readers. Stories of his combat exploits are told in “First to Fight: First Force Reconnaissance in Hue City” (February 2018), and “The Flying Ladder: Emergency Extractions and the Lifesaver from the Sky” (April 2018). During 13 months in country with 1st Force Recon Company, Buda took part in 46 long-range recon patrols along the Laotian border, six combat dive missions, and earned two Bronze Stars with combat “V.” He extended his tour to remain in country, but received his third Purple Heart in January 1969 and was sent home.

As a team leader on deep reconnaissance patrols among large North Vietnamese Army (NVA) formations and staging areas, Buda faced decisions and situations that seem insurmountable. His experience and point of view offered the perfect vehicle to communicate the lessons learned from Vietnam, serving as a living link between the past, present and future of Marine Reconnaissance. Buda developed a class to present to the students of BRC. He based the content on a series of his patrols that best illustrated the role of Recon, the discipline and attitude so vital to success and the types of challenges Marines could one day face in combat. To get the class financially backed and implemented, the RTC cadre turned to Jose Tablada. In addition to his senior role with MARFORPAC, Tablada serves as the president of the Marine Recon Foundation (MRF), a nonprofit organization doing impressive work within the community.

MRF is fully staffed by volunteers—primarily of retired staff noncommissioned and commissioned officers. Even though they exist on behalf of a relatively small contingent of active duty or veterans, the organization has accumulated astounding support. MRF maintains over 325,000 followers between Facebook and Instagram. They operationally support, coordinate, and when necessary, finance a seemingly endless list of programs that provide tangible and immediate help to Reconnaissance Marines, Special Amphibious Reconnaissance Corpsmen, and their families.

Marines take part in the Recon Challenge at MCB Camp Pendleton, Calif., sponsored by the Marine Recon Foundation. The 14th annual event took place in April. (Photos courtesy of Marine Recon Foundation)

The foundation offers reoccurring programs, including retreats for wounded veterans and Gold Star families, and the annual “Recon Challenge” in California. They also provide emergency support to Marines in crisis; for example, helping rebuild the life and home of a Marine and his family after fire destroyed their house or covering the funeral expenses for a Marine lost to suicide and establishing college investment accounts for his children left behind.

The foundation’s final line of effort is dedicated to promoting and preserving the legacy of the Recon community. They accomplish this task through written narratives, audio and video recordings of veterans to capture their experiences, and sponsoring mentorship events where veterans are brought in to speak with active-duty Marines.

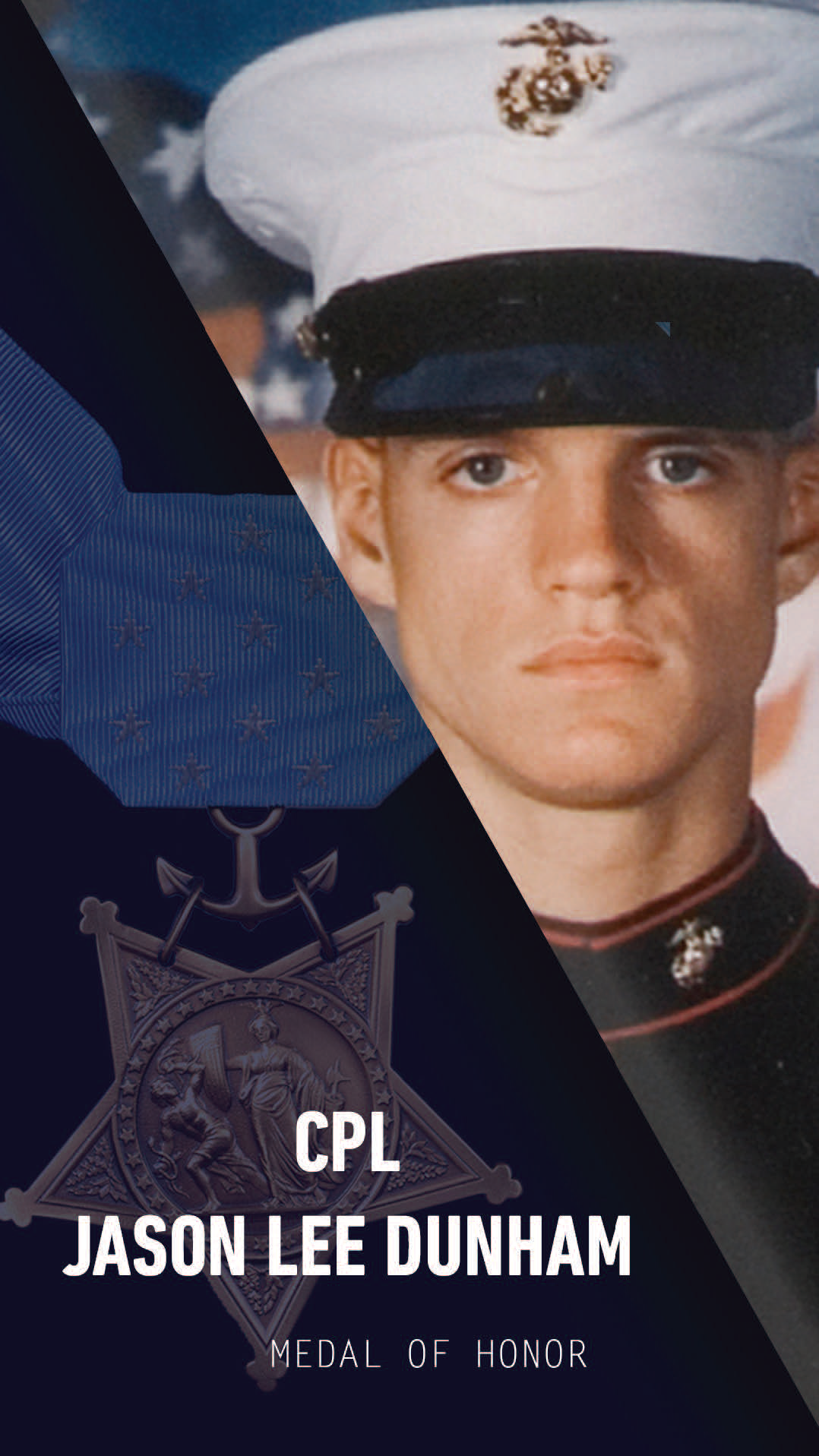

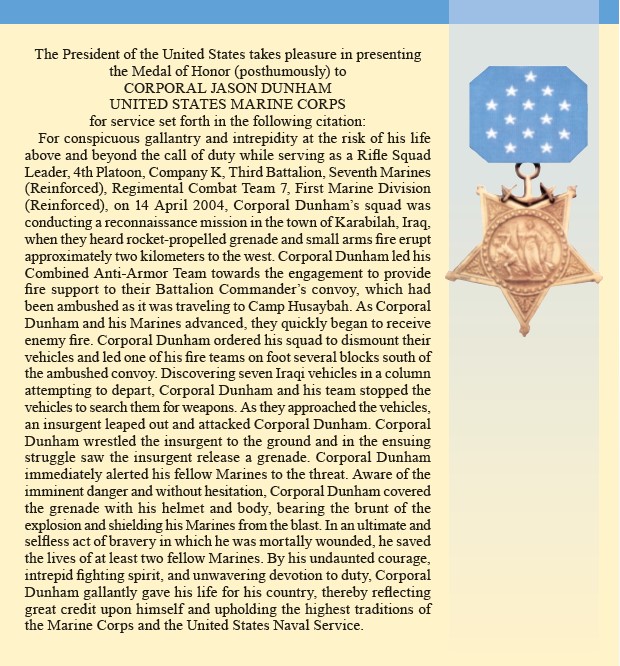

Major James Capers, Lieutenant Colonel George “Digger” O’Dell, and Col Robert Coates are a few of the Marines who participate in mentorship events. Master Sergeant Earl Plumlee, USA, also attends. Before receiving the Medal of Honor as an Army Special Forces soldier, Plumlee served as a Reconnaissance Marine, earning Recon Team Leader of the Year in 2008. He credited his gunfighting skills to his time with Force Recon.

“A lot of Americans don’t know Marine Recon history,” Tablada said. “A lot of Marines don’t know Marine Recon history, and frankly, some of the young Marines and Sailors in Recon don’t know the rich lineage and storied history of their community. We are brought up to be silent professionals. We don’t have a lot of books, there’s no calendars, we aren’t talking on the news. A lot of people just don’t really understand what Marine Reconnaissance is, so through our mentorship program, we send these legends of our history, these senior mentors, down to the active-duty Marines in the fleet or at the schoolhouse to talk to them about their experiences and lessons learned in combat.”

Through the mentorship program, MRF coordinated with RTC staff and arranged for Bob Buda to travel to Camp Pendleton and present his pilot class. The first PME took place in July for a BRC class nearing graduation. Buda walked the students through the evolution of recon tactics in Vietnam, explaining some of the tragic events that led to the successful implementation of standard procedures, such as operating in larger teams, and the immediate action of extreme violence and huge amounts of fire power on enemy contact to stun the enemy and give the team a chance to escape. He covered several specific long-range Recon missions in which he took part, including the missions covered by Leatherneck in previous stories. These case studies presented the students with real situations that can be faced in combat, and the types of challenges they could encounter.

“When you’re out on a long-range Recon mission, the terrain and environment will often be harder to deal with than the enemy,” Buda stated. “It’s just extreme hardship, and you have to learn to develop the right attitude in your head.”

The class was so well-received that RTC staff invited Buda back the following month to present to the students of the Recon Team Leader’s Course. This more senior group of warriors also included USSOCOM Special Operations Forces personnel from other branches of service. Buda tailored his presentation to highlight the vital role the team leader plays in the success or defeat, life or death, of their team.

Combat decision making occupied a central theme in the team leader’s course presentation. To open the discussion, Buda presented the group with a case study on one of his patrols where a Marine was killed by enemy fire after the team encountered a NVA antiaircraft gun that was turned on them. The Marines successfully eliminated the gun with nothing but their organic small arms, the only Force Recon team known to have accomplished such a feat. Despite the victory, Buda faced numerous decisions that day that as the team leader, only he could have made. His choices held direct and immediate sway over the lives of his teammates. To this day, he wrestles with the choices he made, debating if they were correct and if he should have done something differently. These circumstances and thought processes were candidly presented to the students to demonstrate the kinds of situations they will face in the field.

“The most important concept we try to push into the students in BRC, and more importantly the team leaders, is to implant and enhance the concept of the recon brotherhood and the proper team spirit, which is vital to conduct real long-range Reconnaissance missions in the most hostile and challenging environments in the world,” said Buda.

“Attitude and team spirit; those words are easy to say, but the team leader must develop those in order to succeed.”

To close his presentation, Buda highlighted the importance of training your replacement and discussed the warrior who raised him in the field. Buda served as a junior Force Recon Marine under Lawrence H. Livingston. Livingston eventually retired as a giant of the Corps; a Major General, two-war veteran, and recipient of five Purple Hearts, four Bronze Stars, a Silver Star, and a Navy Cross. In Vietnam, Livingston was a staff sergeant who taught Buda how to run point on patrols, and eventually, how to lead a recon team in the jungle. When the Corps plucked Livingston from combat to return home for officer training, he selected Buda to replace him as team leader. Livingston passed away in 2018 at the age of 77. Buda dedicated his presentation in Livingston’s memory.

With the experience of these two classes, Buda continues working to improve the lesson content for future iterations. Tablada and the MRF are committed to sustaining this type of activity as part of their historic preservation line of effort and the Recon Mentor Program. At a minimum, Buda hopes to continue presenting the class as a standard PME included in the biannual team leader’s course.

Marines of every MOS take pride in our history and bear the responsibility of honoring the service of those who went before. The Recon community today exemplifies an enduring truth; no matter what may change in weaponry or technology, Marines today fight as part of the same spirit and enduring legacy, and Marines of eras past are their backbone, offering experience and wisdom from combat that no one else can provide. There are many warriors from Vietnam, like Bob Buda, who volunteer their experience today for the good of the Corps. The Recon Marines preparing for tomorrow’s war will reap immense benefit from hearing his firsthand account of what they will face in combat.

“At the end of the day, it isn’t going to matter how many new accoutrements you have that make you pretty, what rank you are, or how many accolades you may have achieved,” Buda reflected. “At the end of the day, when you’re out of water, out of ammo, you’re starving, surrounded by bad guys, can’t get extracted, soaked by rain, covered in bugs, mud, and shrapnel wounds, the only thing that will sustain you in that environment is if you have deeply cultivated the proper attitude in your team, where they look to each other in those absolutely destitute conditions and someone cracks a contagious smile. You can’t talk. Everything has to be done through hand signals and mental telepathy, but everyone is smiling at each other thinking, ‘I’m ready, and we are still in this fight. Love you brother.’ ”

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps history. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.