Marine Culture—History, Tradition, and Courtesy

Marine Culture—History, Tradition, and Courtesy

Marines through the ages have handed down to their Corps its most cherished traditions:

traditions of duty, self-sacrifice, versatility, and dependability. Today, more traditions emerge or are

reinforced by Marines in action. The thought of failure or letting down one’s brother Marines

remains unthinkable and has inspired new and already legendary feats of exertion and courage

in the pantheon of Marine Corps history.

Marines learn their traditions with equal attention to their packs, rifles, or ammunition.

Pride of person remains part of every Marine. The making of Marines is not alone a matter of

smart appearance, drill, and discipline. Of equal importance, Marines know their culture

and how to live up to it so that they can meet any emergency that may arise and report,

“The Marines have landed, and the situation is well in hand.”

Every Marine carries the colors of the Corps and the United States. These colors repeatedly

have been uncased and cased with new battle streamers. That piece of fabric symbolizes many concepts.

It represents more than a year of an individual life. It recalls the fellow Marines who lost

their lives for the mission and who made the journey home ahead of the rest.

It represents great courage in battle. It represents remarkable stamina over months

and later years. It represents unshakable honor tested in the most complex environment

imaginable. It represents immeasurable personal and Marine Corps family sacrifice.

Symbols of Tradition

The familiar emblem of globe and anchor, adopted in 1868, embodies worldwide service and sea traditions. The spread eagle, the symbol of the Nation itself, holds in its beak a streamer upon which is inscribed the famous motto of the United States Marines: “Semper Fidelis,” which means in Latin “always faithful.”

The term “Leatherneck,” as applied to Marines, is widely used but few people associate it with the uniform. The fact that United States Marines wore a black leather stock, or collar, as part of their uniform from 1798 to 1872 may have given rise to the name. According to tradition, the stock originally was worn to protect the jugular vein from the slash of a saber or cutlass. However, official records fail to bear this out. The sword with a Mameluke hilt, came to Lieutenant Presley N. O’Bannon of the Marine Corps from a former Pasha of Tripoli, later becoming the symbol of authority of Marine Corps officers since 1826. It symbolized the exploits of O’Bannon and his Marines on “the shores of Tripoli” in 1805, an episode climaxed by the raising of the American flag for the first time in the Old World. (See Figure 2-1.)

Marine Origins

The Marine Corps dates from November 10, 1775. On that day, the Continental Congress authorized formation of two battalions of Marines to form part of the naval service. Samuel Nicholas, named the first captain of Marines, remained senior officer in the Continental Marines through the Revolution and is properly considered our first Commandant.

The initial Marine recruiting rendezvous opened at Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, and by early 1776, the organization had progressed to the extent that the Continental Marines were ready for their first expedition. The objective was New Providence Island (Nassau) in the Bahamas, where a British fort and large supplies of munitions were known to be. With Captain Nicholas in command, 234 Marines sailed from Philadelphia in Continental warships. On March 3, 1776, Capt Nicholas led his men ashore, took the fort and captured the powder and arms for Washington’s army. For the first time in U.S. history, the Marines had landed, and the situation was well in hand. (See Figure 2-2.)

Beginnings of the Corps

After an interval in which no organized military forces existed in the new United States, the Marine Corps, as it exists today, was reformed by the Act of July 11, 1798, at the beginning of the Naval War with France. The Marines took part in that war from 1798 to 1801 and in the war with the Barbary pirates from 1801 to 1805. They took an active part in the War of 1812, serving aboard practically all American warships that engaged the enemy; with the Army in the Battle of Bladensburg, August 1814; and with Andrew Jackson at New Orleans.

In 1824, Marines formed part of a landing force, which operated against a nest of pirates in Cuba. In 1832, Marines again saw action against pirates as part of a combined landing force from the U.S. frigate Potomac. Their mission was to punish the Malay pirates at Quallah Battoo, Island of Sumatra, for the capture and plunder of the USS Friendship.

In 1824, Marines from the Boston Navy Yard suppressed a mutiny in the Massachusetts State Prison, which was beyond the control of the civil authorities. During 1836 and 1837, they helped the Army fight the Creek and Seminole Indians in Georgia and Florida, where they served under their Commandant, Colonel Archibald Henderson, who subsequently received a brevet promotion to brigadier general.

The Mexican War

During the war with Mexico and in the conquest of California, the Marines took an important part both on the Gulf and Pacific coasts, assisting in the capture of Monterey, Yerba Buena (San Francisco), Mazatlan, Vera Cruz, Tampico, and Tobasco. One battalion of Marines marched with General Winfield Scott to Mexico City, participating in the final attack on the Castle of Chapultepec and the march to the National Palace, the Halls of Montezuma. Thus came the words that for many years adorned the Corps’ colors: “From Tripoli to the Halls of Montezuma.” We commemorate these battle honors today in the first two lines of “The Marines’ Hymn”— “From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli.

Marine Corps Mottos

Shortly after the Mexican War, the Marines carried the so-called “Tripoli-Montezuma” flag, which had the early motto, “By Land, by Sea.” When the current Marine Corps emblem was adopted in 1868, the Navy Department authorized the current motto, “Semper Fidelis,” on streamers above the eagle soon after the Civil War, and it was officially adopted as the motto in 1880.

The famous American bandsman, John Phillip Sousa, composed the march, “Semper Fidelis,” in the year 1888, during the time when he was leader of the U.S. Marine Band.

The Uniform

Secretary of War James McHenry first authorized the famous blue uniform of the Marine Corps on August 24, 1797, even before the reforming of the Corps with the U.S. Navy. Blue or “Navy Blue,” a conspicuous color of sea and employed generally by the naval forces of all countries, was selected by the U.S. Marines for their uniforms, while the pattern and trimmings of scarlet and gold served at the same time to make them appear distinctive. In view of the fact that the early organization, duties, and regulations of the American Marines were patterned somewhat after ways and customs of their forerunners, the British Royal Marines, it is possible that the traditional red of the British uniform had its effect in the adoption of scarlet for the uniform of the U.S. Marines.

The blue uniform with red trimmings was used from 1797 until July 4, 1834, when it was replaced by a grass green uniform with buff trimmings. This uniform lasted only six years until July 4, 1840, when the blue uniform trimmed with scarlet again was prescribed.

From Civil War to World War I

During the Civil War, Marines served afloat and ashore. A noteworthy incident before the beginning of the Civil War period (1859) was the participation of Marines in the capture of John Brown at Harpers Ferry. The Corps remained small, but Marines served ashore in the Mississippi Valley and in the defenses of Washington. All along the Confederate seaboard, from Hatteras Inlet to Hilton Head and Fort Pickens, shipboard Marines, sometimes in provisional battalions, executed successful landings, which put teeth into the Union blockade. (See Figure 2-3.)

Its strength remained at only 4,161 officers and men. As early as 1864 (and again in 1867), attempts were made to disband the Marine Corps and merge it with the Army. Both times, however, Congress stepped into the breach, and the Corps was saved.

Scattered Actions

The “peacetime” activities of the Marine Corps from the close of the Civil War until the War with Spain, established the Marine Corps tradition of versatility. Marines aided civil authorities in suppressing labor riots in Baltimore and Philadelphia and enforcing revenue laws in New York. At the same time, they participated in expeditions to the Caribbean area, Korea, China, and other foreign countries for the purpose of protecting American lives and property.

During the years 1867 and 1870, they formed part of the Formosa expedition. In 1871, a battalion of Marines, forming part of a naval brigade, led the advance against Korean forts along the Han River in reprisal for serious offenses against Americans. (See Figure 2-4.)

In 1882, a detachment of Marines landed at Alexandria, Egypt, to assist in restoring order.

Spanish War

During the War with Spain, at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Marines again were first to land in enemy territory. They also served aboard ship detachments on battleships and cruisers under Admirals Dewey and Sampson at the naval battles of Manila Bay and Santiago de Cuba. Following the spectacular naval victory in Manila Bay, the Marines from the cruiser Baltimore landed to seize the Spanish Naval Arsenal at Cavite, and from then on, Marines garrisoned this station.

Philippine Insurrection

Concurrent with the War with Spain came the continuation of the Philippine Insurrection, now against Americans instead of Spaniards. This three-year campaign saw the first modern Marine brigade organized, as well as three exploits for which the Corps will be remembered: the march across Samar, the storming of Sojoton Cliffs in Samar, and the pacification of the Subic Bay area on Luzon.

Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion in China, in the summer of 1900, Marines from ships on the Asiatic station took part in the defense of the Legation Quarter at Peking, and Marines formed part of the allied relief expedition that marched from Taku to Peking and fought in the Battle of Tientsin. (See Figure 2-5.)

A tradition of friendship between the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and the United States Marine Corps (USMC) began from this campaign. During the fighting at Tientsin, each of these two famous organizations supported the other on a number of occasions. Their mutual admiration continued, and each Saint David’s Day (March 1) is marked annually by an exchange of messages that contain the ancient Welsh password, “And Saint David.”

Marines elsewhere remained active. In 1903, Marines landed in Santo Domingo and returned in 1905 to Korea, while a detail of Marines served as guards for a diplomatic mission to Abyssinia by camel caravan across the desert to negotiate a treaty with Emperor Menelik II. From 1906 to 1908, the Marines participated in the army of occupation in the Cuban Pacification, a number of expeditions to Panama and Nicaragua from 1909 to 1912 and the 1914 naval expedition that seized Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Marines in World War I

In World War I, the Marine Corps expanded to 75,000 men, guarding ships and stations and forming eight regiments, some of which participated in the fiercest fighting Marines had ever known. The 4th Brigade of Marines (composed of the 5th and 6th Marine regiments and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion) served as one of the infantry brigades of the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division, participating with distinction in the important battles of Belleau Wood, Soissons, St. Mihiel, Blanc Mont Ridge, and the Argonne.

After Belleau Wood, German Army intelligence reports evaluated the Marine brigade as “storm troops”—the highest rating on the enemy scale of fighting men. The French government later renamed the area the “Woods of the American Marines.”

The Marine Corps also sent the 5th Brigade (11th and 13th Marine Regiments and the 5th Machine Gun Battalion) to France, but Army policy relegated them to guard duty. The remaining regiments performed duties in the Caribbean. Marine aviation units under command of Major Alfred A. Cunningham (who had become the Marine Corps’ first aviator in 1912) rendered conspicuous service as the Day Wing of the Northern Bombing Group in Northern France and Belgium. The Marine pilots flew 57 bombing missions, dropping 52,000 pounds of bombs and shooting down at least a dozen German planes.

Women Marines

Opha M. Johnson was the first woman Marine, enlisting on August 13, 1918, the day after the Secretary of the Navy granted the authority to enroll women in the Marine Corps Reserves (MCR) for clerical duty at HQMC and at other Marine offices in the United States.

A total of 305 women enlisted during World War I to “free a man to fight.”

During World War II, the Women’s Reserve began forming in 1943, reaching a total of 821 officers and 18,000 enlisted women led by Colonel Ruth C. Streeter. This was roughly the equivalent of one division of men free to fight. The end of the war brought demobilization for most women, but in 1948, they reformed as the Women Marines in the regular and reserve Marine Corps

Between Two Wars

For more than a decade after World War I, Marines continually engaged in efforts to restore peace in the countries of the Caribbean area—always acting as the strong arm for carrying out the Nation’s foreign policy.

In three Caribbean countries, they carried on extensive campaigns against insurgent elements, assisting the governments of those countries to put down armed insurrection, and to organize efficient native constabularies (in which many Marines served) to maintain order after they withdrew.

In Haiti from 1915 to 1934, Marines fought two wars with the Cacos; in the Dominican Republic, it took them eight years to suppress banditry, and in Nicaragua, they fought the bandit elements from 1927 to 1932. (See Figure 2-6 and Figure 2-7.) The fighting in Nicaragua was the first evidence of the development of the famous Marine “air-ground team” concept that would later take shape as the MAGTF. Cargo resupply by aircraft also was used for the first time.

Duty in China

For almost a century, the Marines called China a duty station. As early as 1854, internal upheaval that endangered the lives of Americans required the presence of a landing force of Marines. From that time to the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Marines and sailors landed on a number of occasions for the protection of our national interests. The decade from 1901 was a comparatively peaceful one, but in 1911 and 1912, Marines operated in China to protect Americans during the popular overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty.

Beginning in 1924, contingents of Marines and sailors landed from time to time to protect American citizens and American interests. In 1927, upheavals of civil war in that country and the attending danger to Americans brought forth a force of about 5,000 Marines, dispatched and stationed at various trouble points, principally at Shanghai and Tientsin. Two aircraft squadrons, Fighting Three and Observation Five (VF-3M, VO-5M), formed the aviation component. During the next two years, Marine aviators flew more than 3,000 sorties, mostly reconnaissance.

By January 1929, the situation having improved, the force, which had grown into the 3rd Marine Brigade, returned to the United States after order had been restored, with the exception of the 4th Marines, which remained in Shanghai. The 4th Marine Regiment remained on duty in China until withdrawn just before the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Fleet Marine Force

In 1933, the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) came into being, initially on paper, as an integral part of the United States Fleet. The troops regularly assigned to this organization were mostly stationed at San Diego, California, and Quantico, Virginia, and trained for their specialized duties as Marine expeditionary troops forming an integral part of the U.S. Fleet by participation in the annual maneuvers of the Fleet. (See Figure 2-8.)

At each of these stations the Marine Corps planned a reinforced brigade consisting of an infantry regiment, a battalion of light field artillery (pack howitzers), a battalion of antiaircraft artillery, an aviation group, a light tank company, and small contingents of engineer and chemical troops. The aviation planned at each of these posts comprised two fighting squadrons, two bombing squadrons, one observation squadron, and one general-utility squadron. However, the strength of the peacetime Marine Corps only permitted establishing the 1st Brigade at Quantico, with only the smaller 6th Marine Regiment stationed at San Diego. In its final year and a half of peace, the Marine Corps would grow not only in structure but in mission. Already in July of 1940, the Joint War Planning Committee Board planned the use of the 1st Marine Brigade to seize the Vichy-French island of Martinique as well as the Azores Islands in the Atlantic. The Corps thus was thrust into the same two-ocean war as the Navy, having thought mostly of Pacific campaigns for the FMF thus far in its existence. War planning now called for an FMF consisting of two complete divisions, several base defense battalions and two aircraft wings.

Marines in World War II

In 1941, Marine units stood on duty halfway around the world, with approximately 2,000 Marines serving in China and the Philippines under the command of the Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet. In addition, several thousand Marines were serving at naval stations in the Hawaiian Islands, Guam, Wake, Midway, American Samoa, the Panama Canal Zone, and Cuba.

The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, taken largely from the new 2nd MarDiv at San Diego, occupied Iceland, and provisional Marine companies guarded various islands in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean.

The Japanese Attack

When the Japanese struck in the Pacific, the Marines from the stations in China had been successfully withdrawn to the Philippines with the exception of the Marine detachments at Beijing and Tientsin in North China. The Marine garrisons at Cavite and Olongapo in the Philippines participated in the defense of Bataan and Corregidor, until the American forces were finally overpowered and captured by the Japanese. The handful of Marines on Guam put up a heroic but futile defense. On Wake Island, the detachment of 1st Marine Defense Battalion, supported by fighter squadron VMF-211, repulsed the first Japanese landing attempt. This act stunned the Japanese with their first defeat of the war. A second landing was made by the Japanese on December 23. After a full night and morning of fighting, the Wake garrison surrendered to the Japanese. Marines lost 49 killed during the entire 15-day siege, while 3 U.S. Navy personnel and at least 70 civilians were killed. Japanese losses were recorded at between 700 to 900 killed, with at least 1,000 more wounded, in addition to the two destroyers Marines sank in the first invasion attempt and at least 28 landbased and carrier aircraft either shot down or destroyed. In Hawaii, an aircraft group consisting of one fighter and two dive-bomber squadrons was almost completely put out of action by the Japanese raid.

Marines to the Defense

Immediately after the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, additional Marines with defense battalion equipment were sent out from the United States to reinforce the Hawaiian Islands and the smaller islands (Midway, Johnston, and Palmyra) lying to the west.

At the same time, measures were taken to strengthen the chain of islands across the South Pacific that protected the line of communication to Australia. The 7th Defense Battalion of Marines had been stationed at Tutuila, American Samoa, since March 15, 1941, and had taken some steps toward fortifying the harbor at Pago Pago.

As further reinforcements for this important position, a brigade of Marines, the 2nd, taken mostly from the 2nd MarDiv at San Diego, was formed and together with Marine Aircraft Group 13 (MAG-13) preceded early in January of 1942 to American Samoa and set up defenses and air facilities on Tutuila.

An additional brigade of Marines, the 3rd, was organized from units of the 1st MarDiv at New River, North Carolina, and sent to Western Samoa, where they arrived on May 8, 1942. This brigade took up and organized positions on Upolu and Savaii Islands and, with naval units, established important air and naval facilities. The westward thrust of the Marines was resumed in October 1942 when a part of a Marine defense battalion occupied the island of Funafuti in the Ellice Islands.

Guadalcanal

In order to secure our line of communication to the southwest Pacific and prepare for the eventual Allied counteroffensive, the 1st MarDiv sailed to New Zealand in June of 1942. Even before they arrived in New Zealand, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift read orders for his division (reinforced by the 2nd Marines of the 2nd MarDiv, the 1st Raider Battalion and the 3rd Defense Battalion) to carry out an amphibious assault in the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area.

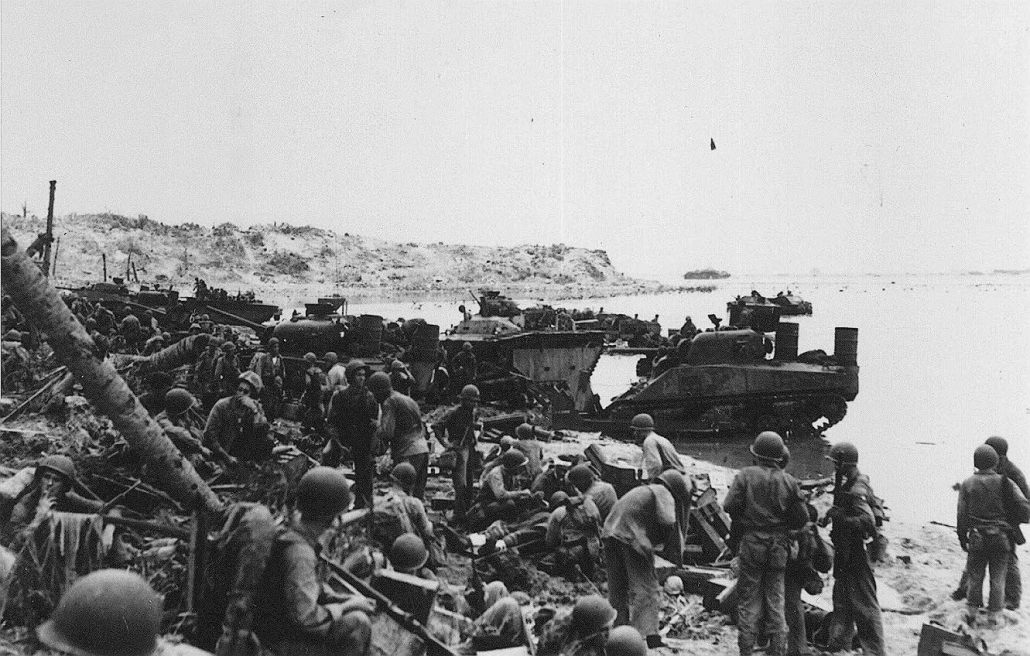

On August 7, 1942, the 1st MarDiv landed on the north coast of the islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida. This amphibious assault marked the beginning of the United States offensive against the Japanese empire. By August 10, the Marines had destroyed the Japanese garrisons at Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo and had secured the airfield the Japanese had begun on Guadalcanal. (See Figure 2-9.)

For the next four months, the 1st MarDiv, later reinforced by Army troops and additional elements of the 2nd MarDiv, supported by the ships and aircraft of the Navy and planes of the Army and the Marine Corps, successfully repulsed numerous Japanese attacks made by land, sea, and air. This bitterly fought and grueling campaign was highlighted by the battles of the Tenaru River, the Matanikau River, and Bloody Ridge. Officers and enlisted men of the 1st MAW performed almost legendary feats in fighting off Japanese air attacks at Guadalcanal and carrying the fight to enemy ships and bases.

Up the Solomons

After winning Guadalcanal, seen as the first stepping-stone to Tokyo, our forces moved up the Solomons Island chain and seized bases in the New Georgia Islands. Army and Marine Corps units had landed on the Russell Islands in February of 1943, which gave us an air base for operations against enemy bases in the New Georgia group.

In June and July 1943, Marine Corps and Army troops landed on New Georgia and Rendova Islands, followed by landings on Vella Lavella, Arundel, and Kolombangara Islands.

The culmination came on November 1, 1943, when the 3rd MarDiv made a landing at Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville. The Bougainville campaign marked the beginning of close-air support in the modern sense. For the first time pilots (forward air controllers) and enlisted men (radiomen) from the wing reported to the division for duty, where they helped company and battalion commanders obtain and direct air attacks on specific enemy emplacements holding up the advance of the Marine ground units.

During the next 45 days, the 3rd MarDiv fought off Japanese counterattacks and expanded the beachhead to eventually hold vital air bases. The Marines handed off the swampy, mosquito-infested island to the Army for the mopping up of resistance.

The Gilberts

After the seizure of Bougainville, the Allied offensive against Japan was intensified. Army forces accelerated their leapfrog tactics up the north coast of New Guinea, and our Central Pacific forces breached the Japanese outer line of defense when on November 20, 1943, the 2nd MarDiv landed on Tarawa, and elements of the Army 27th Division went ashore on Makin Island, both in the Gilberts Group.

Within four days, the Marines had wiped out all enemy resistance on Tarawa but had suffered very heavy casualties. The Japanese had boasted that a million Americans could not take the triangular coral atoll of Tarawa, where the island of Betio contained the Japanese base … not in a hundred years. It took the Marines 76 hours. (See Figure 2-10.)

Robert Sherrod wrote: “The Marines fought almost solely on espirit de corps, I was certain. It was inconceivable to most Marines that they should let another Marine down, or that they could be responsible for dimming the bright reputation of their Corps. The Marines simply assumed that they were the world’s best fighting men. Of the 4,836 Japanese soldiers and Korean laborers on Betio, only 146 were taken prisoner.”

In the meantime, American and Australian forces cleared New Guinea’s north coast, and on December 15, 1943, crossed to Arawe, New Britain, supported by Marine tanks in a drive aimed at cutting the Japanese southern coastal line of communications to Rabaul.

On December 26, 1943, the 1st MarDiv went ashore on Cape Gloucester on the western end of New Britain, cutting the enemy northern line of coastal communications and forcing the enemy to fall back on their main base at Rabaul. In a series of bloody battles, Marines secured the Cape Gloucester airdrome and captured a number of strategic hills in the Borgan Bay area.

By March of the following year, the Japanese were fleeing eastward toward Rabaul. On April 28, 1944, the Commanding General of the 1st MarDiv turned over command of the Cape Gloucester area to the Army.

The 1st MarDiv’s operations in the western New Britain placed U.S. forces, particularly aviation, in a half circle around Rabaul, their major base that once had threatened Allied communications with Australia. Now it became a strategic prisoner-of-war stockade as the Pacific War moved on toward Japan.

The Marshalls and Marianas

Farther to the north, our Central Pacific forces smashed through the Japanese defensive line by seizing a number of islands in the Marshalls group.

The 4th MarDiv, proceeding from their training base at Camp Pendleton, California, assaulted and captured Roi and Namur Islands at the northern end of Kwajalein Atoll, while the Army’s 7th Infantry Division seized Kwajalein Island at the southern end. Organized enemy resistance ceased on Kwajalein Atoll on February 7, 1944. Japanese resistance proved so weak that the landing force reserve, the 22nd Marine Regiment, launched against Eniwetok Atoll, seizing this important fleet anchorage on February 18 to facilitate the next stop, the Marianas, the main line of resistance in the Japanese island defense system.

The new III and V Amphibious Corps consisting of Marine Corps and Army infantry divisions now turned to confronting large units of the Japanese Army, defending large Pacific islands presenting all possible variations of terrain.

The Marianas formed the inner island defense barrier of Japanese strategy for the Pacific War, and a decisive battle fought on land, at sea, and in the air settled the fate of the Empire. On June 15, 1944, the 2nd and 4th MarDivs (V Amphibious Corps) landed on Saipan, followed in by the 27th Infantry Division. On July 9, after 25 days of heavy fighting, all organized enemy resistance had ceased, and the island was officially secured.

Eleven days later, July 21, 1944, the III Amphibious Corps, composed of the 3rd MarDiv, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade and the 77th Infantry Division, began landing on Guam. Organized resistance ceased on Guam August 10, 1944. (See Figure 2-11.)

Three days after the landing on Guam, the 2nd and 4th MarDivs went ashore on Tinian and completed its seizure on August 1. On November 23, 1944, Marianas-based B-29s made their first raid on Tokyo and brought the war directly to the Japanese homeland.

Defeating Japan

The succession of Central Pacific battles—Tarawa (1943), the Marshalls, Saipan, Guam, Tinian, Peleliu (all 1944), Iwo Jima and Okinawa (both 1945)—was by hard necessity a series of frontal assaults from the sea against positions fortified with every refinement that Japanese ingenuity and pains could produce. To reduce such strongholds, the amphibious assault came of age.

On the morning of February 19, 1945, hundreds of landing boats roared through the pounding surf to spill thousands of V Corps’ 4th and 5th Division Marines onto Iwo’s southeastern beaches. The 3rd MarDiv was held in reserve, landing when room became available on the small island. (See Figure 2-12.) On the morning of February 23, members of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines crested Mount Suribachi crater. A 40-man patrol of Company E crawled to the lip of the crater and raised the first flag, photographed by Leatherneck magazine photographer Technical Sergeant Louis Lowery. Meanwhile, a larger flag was procured; this flag raising became the outstanding symbol of America’s war effort. Six men were depicted in the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo.

In the final great land battle of the Pacific area, the invasion of Okinawa, the Marine Corps was represented by the 1st and 6th MarDivs of the III Amphibious Corps, under the U.S. Tenth Army, landing on the western beaches of Okinawa on April 1, 1945. After mopping up the lightly held northern half of the island, the Marines joined the Army divisions in breaking the main resistance in the south, playing major roles in the final victory, joined in the end by the 8th Marines, 2nd MarDiv. (See Figure 2-13.)

Marine aviation flew more than 14,000 close-air-support sorties in the Okinawa campaign, more than half of them in support of Army troops. Marine nightfighters also recorded a highly increased effectiveness as they held off increasingly desperate Japanese air attacks. Meanwhile, other Marine aviators were fulfilling the U.S. Marine tradition of being ready for any emergency. Japanese kamikaze planes threatened to overcome the air superiority of U.S. aircraft carriers. During the first six months of 1945, the Marine fighter squadrons moved from landbases in the southwest Pacific to aircraft carriers to increase defensive capabilities of the fleet.

The successful conquest of Okinawa enabled our ships, planes, and submarines to tighten the blockade around Japan’s home islands and sever her vital sea links to the Asiatic mainland and the resource areas to the south. On September 2, 1945, in a brief but solemn ceremony aboard the battleship Missouri, representatives of Japan signed the surrender documents. Thereafter, Allied occupation of Japan and the overseas territory under Japanese control went steadily ahead, with Marines playing an important role.

Demobilization and Peacetime Posture

By the end of the war, the FMF, with aviation and ground units, were poised for the invasion of Japan—an invasion rendered unnecessary by U.S. sea and air power and the use of the atomic bomb. The Corps had grown from 19,354 in 1939 to nearly 500,000 in 1945. The victories in World War II cost the Corps 86,940 casualties. In the eyes of the American public, the Marine Corps was second to none and seemed destined for a long and useful career. Admiral Nimitz’s ringing epitome of Marine fighting on Iwo Jima very well might be applied to the entire Marine Corps during World War II: “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

After brief occupation duty in Japan, the 2nd MarDiv and 2nd MAW moved to North Carolina, and the 1st Division and 1st MAW to southern California after duty in postwar China.

Continued Development of Amphibious Techniques

Intensive effort was made in the Marine Corps after World War II to develop and perfect the techniques and equipment associated with amphibious warfare. New concepts emerged in transport submarine operations; air transport, and especially helicopter transport of troops; cold-weather operations; and improvement of amphibious vehicles and weapons. Marines continued their heavy schedules of training troops of all services for amphibious operations. (See Figure 2-14.) In support of this growing program, the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico were reorganized in 1950 into two major subdivisions, the Marine Corps Education Center and the Landing Force Development Center.

“Pathbreakers”

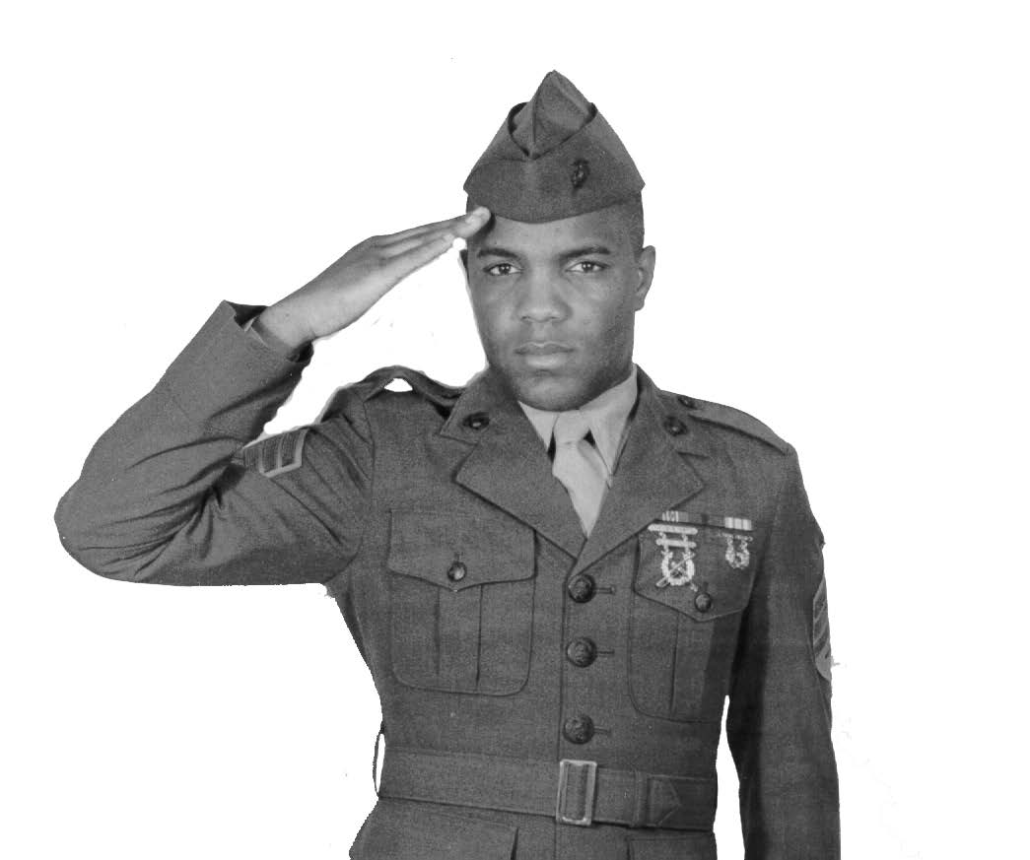

African-American Marines

African American Marines were initially segregated from normal recruit training sites and were sent to Montford Point (renamed Camp Johnson), which is adjacent to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to conduct training. Approximately 20,000 African American Marines were trained at Monford Point and went on to serve with honor and distinction.

Navajo Code Talkers

Code Talkers were Navajo men who transmitted secret communications on the battlefields of WWII. At a time when America’s best cryptographers were falling short, these modest Native Americans were able to fashion one of the most ingenious and successful codes in military history. They drew upon their proud warrior tradition to brave the dense jungles of Guadalcanal and the exposed beachheads of Iwo Jima. Serving with distinction in every major engagement of the Pacific theater from 1942 to 1945, their unbreakable code played a pivotal role in saving countless lives and hastening the war’s end.

Marines in Korea

On June 25, 1950, the Communist North Korean Army invaded the Republic of South Korea. The President alerted U.S. forces in the Far East to render all possible assistance, and the Security Council of the United Nations called on all members to do the same. When Army-occupation troops from Japan proved unable to stem the North Korean invasion, reinforcements, including U.S. Marines, began to embark for the peninsula.

Within two weeks of the alert, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, consisting of the 5th Marines (Reinforced) and Marine Aircraft Group 33, formed and embarked in shipping from California bases, with the first loaded ships sailing on July 12. (See Figure 2-15.)

First offensive action against the enemy was made by MAG-33’s fighter-bombers on August 3, and the brigade first engaged the enemy ashore on August 7. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was attached to the Eighth U.S. Army in the Pusan Perimeter at the time when the North Korean advance had come within 35 miles of Pusan. The battle became one of holding actions against aggressive enemy attacks, and the Marine brigade fought as did a few Army units as “firemen”—hard-hitting mobile reserves that shifted from one threatened area to another for counterattacks. Three times the Brigade helped roll back the enemy in such operations. The famous Marine Corps “air-ground team” immediately began to prove the soundness of the post war developments in close-air support.

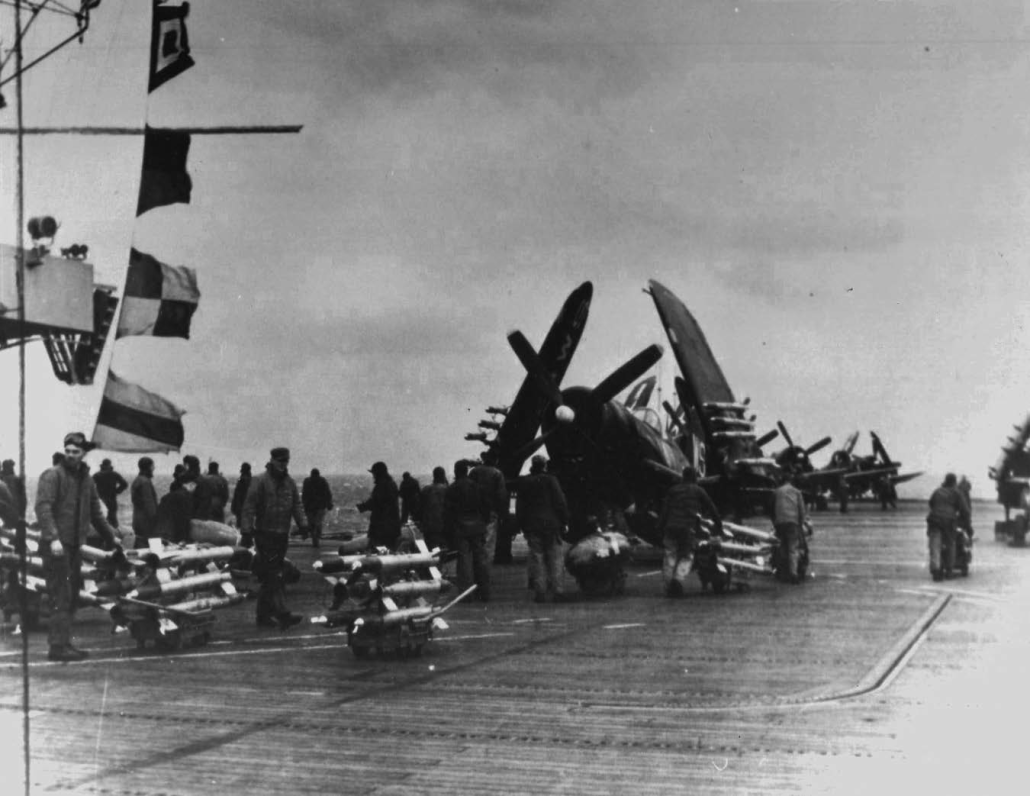

The Inchon-Seoul Landing

September 15, 1950, was D-Day for the 1st MarDiv, landing at Inchon, a daring amphibious assault that led to the capture of Seoul and the seizure of Kimpo airfield as a base of operations for the 1st MAW units and the outflanking of the entire North Korean Army. Within 24 hours, Marines had secured this west coast Korean seaport and swept on, covered by F4U Corsairs of MAG-33, which alternately attacked, screened with smoke, observed and kept the sky free of enemy aircraft. (See Figure 2-16.)

The enemy recovered enough to resist Marine Corps and Army units along the approaches to Seoul, and three days of street fighting were necessary to secure this city of a million and a half prewar population. The end of the war seemed likely as Marines pushed north of Seoul to seize Uijongbu and the main road to the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. On October 7, the 1st MarDiv was relieved by advancing Eighth Army elements and sent by sea around the peninsula.

Chosin Reservoir

After an administrative landing at Wonsan on October 25, the 1st MarDiv carried out patrolling and blocking missions under the Army’s X Corps around Hamhung on the east coast, while advancing inland toward the Chosin Reservoir.

On November 3, the 7th Marines encountered the first of many Chinese Communist Forces (CCF). On November 26, the advancing Eighth Army in western Korea and X Corps in the northeast came under attack by massed Chinese forces in overwhelming numbers. On the night of the 27th, the Chinese attacked the 5th and 7th Marines, which had advanced together to Yudam-ni, west of the Chosin Reservoir. Other Chinese divisions cut the main supply route. From November 28 to December 2, the 1st MarDiv held its own against several such divisions and began a fighting withdrawal, bringing out shattered Army units with it.

Over 70 miles of tortuous road through mountain passes and canyons dominated by CCF, Marines fought and advanced back to the coast, reuniting all of the regiments of the 1st MarDiv that had deployed along the way. The Chinese troops hovering along reverse slopes and flanks became targets for the supporting aircraft of the 1st MAW.

The 1st MarDiv reached Hamhung on December 11, having brought out its wounded, most of its dead, and vehicles and equipment, including those of several Army units. The main body was evacuated on the 15th to South Korea by the Navy, which pulled out the remaining units of X Corps and 91,000 civilian refugees to complete its “amphibious landing in reverse.”

Stopping the Chinese Advance

Upon arrival at Pusan, the 1st MarDiv again passed into Eighth Army reserve. Marines then participated in Operation Killer and Operation Ripper, limited offensives in east central Korea designed to keep the enemy off balance. Meanwhile, operating under 5th Air Force control, 1st MAW planes performed interdiction missions, seeking enemy military targets far into North Korea. The Chinese struck back with a large-scale counterattack. The 1st MarDiv at the Hwachon Reservoir, also known as “The Punchbowl,” beat off repeated enemy attacks, inflicting heavy enemy casualties, stopping the advance of the Chinese and North Koreans, and stabilizing the lines. A second enemy offensive was stopped the following month. This was followed by attacks in which the Marines pursued and severely punished the enemy.

Truce Talks

Marines ended their first year in Korea in the “Punchbowl” area just north of the 38th parallel, former dividing line of North Korea and South Korea. Early in July 1951, United Nations, Chinese, and North Korean representatives met for the first peace talks, which created a lull in the activities at the front. During 1952, Marines continued experimenting with troop and supply lifts, using helicopters to bypass Korean hills. Beginning on Saint Patrick’s Day, the 1st MarDiv was shifted to the extreme west side of the Korean Peninsula. There, Marines fought their last engagements in a series of outpost fights on a static battlefield. The truce came on July 27, 1953, but the 1st MarDiv did not return to the United States until 1955, after almost five years of outstanding service in Korea. The 1st MAW remained in Japan to support the newly reformed 3rd MarDiv.

Marine Corps Readiness

The U.S. rearmament for the Cold War in the face of the fighting in the Korean War included legislation endowing the Marine Corps with a minimum peacetime strength of three combat divisions and three aircraft wings, with supporting troops. The Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) also was authorized full status with the other service chiefs in the Joint Chiefs of Staff in matters directly concerning the Corps. The 3rd MarDiv reactivated on January 7, 1952. It deployed to Japan the following year. The 3rd MAW reactivated on February 1, 1952.

In the decades following the Korean War, the Marine Corps resumed the role of the Nation’s force-in-readiness. To fulfill this mission, two regiments of the 3rd MarDiv deployed to bases on the island of Okinawa, Japan, in mid-1955, and one regiment deployed to Hawaii as the nucleus of the permanent 1st Marine Brigade.

Camp Pendleton is “home” for the 1st MarDiv and the I MEF. The huge base was named during World War II in honor of Joseph H. Pendleton, who served the Corps for 40 years. He was a veteran of the Spanish-American War and the “Banana Wars” of Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic. He died in February 1942 after retiring as a major general of Marines.

Meanwhile, the 2nd MarDiv, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, continued to provide landing forces for the U.S. Sixth Fleet on duty in the Mediterranean and First Fleet in the Atlantic.

Camp Lejeune was named in honor of John Archer Lejeune, the 13th CMC who served as a Marine officer for nearly 40 years. During World War I, he became the first Marine officer to command an Army division. He was appointed CMC in June 1920 and is credited with establishing the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia, and directing the Marine Corps toward its role as an amphibious force-in-readiness. He retired in 1929 and died in November 1942. Camp Lejeune is the “home” of the 2nd MarDiv and II MEF.

In the years following the hostilities in Korea, the Corps’ activities proved as varied as they were scattered. In August 1953, Marines of the Sixth Fleet assisted in relief activities following an earthquake in Greece. Elements of the 2nd MarDiv cruised off the coast of riot-torn Guatemala during July 1954, prepared to land security forces if necessary. In the summer of 1958, the government of Lebanon requested U.S. troops to bolster its army against a growing rebel threat. On July 15, the first of four Marine Corps battalions landed at Beirut. Additional American forces reinforced the Marines who, after the crisis had subsided, withdrew on October 4.

While peacetime operations continued, the Marine Corps also developed concepts, tactics, and equipment to continually update its readiness. In 1948, Marine planners began work on the development of an integrated amphibious and heliborne force designed for a rapid assault from the sea. (See Figure 2-17.) Eventually, this concept gave birth to the Navy’s amphibious assault ship (LPH), a combat vessel capable of carrying a Marine battalion landing team (BLT) and a medium helicopter squadron (HMM). The early LPHs were converted aircraft carriers, but in 1961, the Navy commissioned the first ship specifically designed to support such a force, USS Iwo Jima. To provide close air support for an expeditionary force, the Marine Corps developed the short airfield for tactical support (SATS). Rapidly installed on prepared ground, this landbased carrier deck consisted of 4,000 feet of aluminum matting, catapult, arresting cable, and portable control units to base Marine attack aircraft ashore with the landing force.

The 1960s

Two main areas of conflict loomed next for the Marine Corps–Southeast Asia and the Caribbean.

Following Communist insurgent invasion of Laos in late 1960, BLTs on board Seventh Fleet ships in the South China Sea remained on alert for possible deployment, and the following year, Marine helicopters provided logistical support for the Laotian government. In May 1962, a Marine expeditionary unit, a BLT with helicopter and fixed-wing squadrons, reinforced Thailand because of similar insurgent threats.

Meanwhile, HMM-362 deployed from 1st MAW to Vietnam, where the helicopter squadron flew combat missions in support of the South Vietnamese armed forces. Under the code name Shu-Fly, the air crews operated in the Mekong Delta and later deployed to Da Nang in the northern military district, called I Corps. This initial Marine commitment to South Vietnam reached approximately 600 men, including advisors to Vietnamese ground units.

In October 1962, came the major Cold War crisis with the Soviet Union in the Caribbean when U.S. intelligence reported the installation of Soviet offensive missiles at several bases in Communist Cuba.

President John F. Kennedy issued an ultimatum to the Russian and Cuban governments, demanding the removal of these weapons and simultaneously ordered U.S. forces into the region. In response to this alert, the Marine garrison at the U.S. Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, received reinforcements and combat elements of the 2nd MarDiv, and the 2nd MAW deployed to forward positions for an immediate reaction. An expeditionary brigade from the 1st MarDiv arrived shortly off the coast of Cuba. These and other demonstrations of American resolve led to delicate negotiations that eventually resulted in the removal of Russian missiles from Cuban soil.

Conflict in South Vietnam and the Dominican Republic

In early 1965, Marines conducted two important landings, one of which would commit the Corps to one of the longest wars in its history. The U.S. Navy skirmished briefly with North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Tonkin Gulf incident of August 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes against selected North Vietnamese bases.

During February, the Viet Cong VC, (North Vietnamese directed insurgents in South Vietnam) attacked two U.S. installations in South Vietnam, killing several Americans, while U.S. planes bombed North Vietnam. To guard against Communist retaliatory air strikes, the Marine Corps deployed the 1st Light Antiaircraft Missile Battalion from Okinawa to Da Nang Air Base for air defense.

On March 8, 1965, the 9th MEB, began landing at Da Nang, bringing additional security to the base, and by March 12, some 5,000 Marines stood ashore, sent from the III MEF headquartered on Okinawa.

Two days later, an additional battalion from the 1st Marine Brigade in Hawaii arrived at Phu Bai, seven miles south of Hue. The Marines took up defensive positions at both enclaves, but conducted no major offensive operations against insurgents. They did, however, bolster the South Vietnamese forces who were losing ground to the VC.

Halfway around the world, the 6th MEU moved into another trouble spot.

On April 24, 1965, the Navy’s Task Group 44.9, with BLT 3/6 and HMM-264 embarked, received orders to move close to the coast of the Dominican Republic, then being rocked by internal disorder. The U.S. ambassador had reported that a coup was in progress against the existing government and the Marines were to stand by for possible evacuation of Americans and other foreign nationals.

With the rebels in control of the capital city of Santo Domingo, 500 Marines landed on April 28, 1965, to protect the refugees, since the local police could no longer handle the situation. As conditions continued to deteriorate, additional elements of the 6th MEU were committed to protect civilians and the U.S. Embassy. By the 29th, some 1,500 Marines were ashore. The next day, U.S. Army airborne units arrived, and on May 1, the Corps activated the 4th MEB for operations there. Marine and Army troops engaged rebel bands in sporadic firefights, and there were numerous sniping incidents.

On May 6, the Organization of American States voted to send an Inter-American Peace Force to help restore peace and constitutional government in the Dominican Republic. The first contingent of Brazilian troops arrived on May 25, and the Marines began their withdrawal. On June 6, the last elements of the 4th MEB departed Santo Domingo, having controlled some 8,000 Marines either ashore or afloat off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Final Marine casualties were 9 killed and 30 wounded.

Establishment of III MAF

As the 4th MEB departed Santo Domingo, the Marine Corps accelerated its commitment to the Republic of Vietnam. On May 3, 1965, 9th MEB stood down and the III MEF established itself ashore, along with the 3rd MarDiv (Forward). At that time, ground elements consisted primarily of the 3rd Marine Regiment, and all aviation units were under the control of MAG-16.

On May 11, the 1st MAW (Advance) arrived at Da Nang to provide the senior headquarters for all Marine aviation in the country. The designation of III MEF was changed to III Marine Amphibious Force (MAF) on May 7, a cosmetic change in name only. The same day, the 3rd MAB landed at Chu Lai, 55 miles south of Da Nang and established the third Marine enclave in I Corps. Two days after this landing, Marine engineers and U.S. Navy Seabees began construction of a SATS field at Chu Lai.

Laboring under extremely adverse conditions, the working parties completed an operational strip by June 1, when the first A-4 Skyhawks of MAG-12 arrived. As of June 5, the Marine Corps leadership in III MAF exercised U.S. military command over all I Corps responsible to the Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam headquartered in Saigon. The Marine Corps still maintained a defensive posture in Vietnam with orders to conduct only those limited offensive operations necessary to ensure the security of its base perimeters.

Full-Scale Combat Operations in Vietnam

On July 1, 1965, Viet Cong assault squads launched their first attack on the Da Nang air base, and it became apparent that the Marines would have to expand their areas of responsibility and conduct deep patrolling to prevent further attacks. This decision coincided with the August arrival of the 7th Marines (1st MarDiv) at Chu Lai.

Within four days of landing, Regimental Landing Team (RLT) 7 took part in the first major American battle of the war—Operation Starlite. By the end of 1965, there were 38,000 Marines in I Corps, with more on the way. In January 1966, the President authorized the deployment of the 1st MarDiv to Vietnam. The division established its headquarters at Chu Lai on March 29, 1966, and held responsibility for the two southern provinces of I Corps. From its headquarters at Da Nang, the 3rd MarDiv took over the central and northern provinces.

Marines knew the war in Vietnam was not entirely a military struggle. In a counterinsurgency environment, the people were the key to success, and III MAF initiated several programs to win the support of the populace.

In late 1965, Marines initiated Golden Fleece operations whereby units protected the villagers’ rice crop from the guerrillas during harvest time. This effort proved so successful in denying the VC logistical support that commanders expanded the program throughout I Corps.

County Fair was a combined U.S./ARVN (United States/Army of the Republic of Vietnam) cordon-and-search process aimed at the local guerrillas. Moving into position before dawn, the Marines threw a cordon around a target hamlet to prevent the VC from escaping or receiving reinforcements. At last light, South Vietnamese troops entered the hamlet, where they took a census, fed the people, provided medical attention and entertainment, and searched the area. Those VC who were not killed or captured were disposed of by the Marines when they fled the hamlet.

With the Combined Action Program, begun by the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, at Phu Bai, Marines reverted to their traditional antiguerrilla technique for the villagers by preparing the militia-like Popular Forces (PF) for local defense. The basic operating unit integrated a 14-man Marine squad, with a Navy Corpsman, with a 35-man PF platoon, forming a Combined Action Platoon (CAP). The Marines lived in the village, assisting in the military training of the PFs and initiating self-help projects for the peasants. These local defense groups soon were able to deny the VC access to rice and recruits from the hamlets and provided the villagers with a life free of insurgent terror and intimidation. By late 1966, the various pacification and civic action programs, shielded by Allied military operations, had extended government influence over 1,690 square miles and 1,000,000 people in I Corps.

War in the North

As a result of allies military and pacification successes along the coastal plain, the North Vietnamese opened a new front along the northern border of I Corps. In July 1966, the 324th NVA (North Vietnamese Army) Division moved south across the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in its first major incursion. Besides seizing Quang Tri Province, the enemy hoped to draw the Marines away from the populated areas, thin out their forces and take pressure off the VC insurgents in the south.

In Operation Hastings, Marine commanders pitted 8,000 Marines and 3,000 South Vietnamese troops against the enemy division. Heavy fighting continued until August 3, when the 324th retreated to the north, leaving over 700 dead behind.

To counter the threat from the north, the 3rd MarDiv displaced to Phu Bai in October. 1st MarDiv, then shifted to Da Nang as U.S. Army troops moved into the Chu Lai area, thus freeing Marines for duty farther north. In the spring of 1967, the 325th NVA Division made a thrust into the south, this time against the combat outpost at Khe Sanh. Two battalions of the 3rd Marines responded and, behind pinpoint bombing of Marine attack aircraft as well as massive artillery fire, drove two enemy regiments from the hills overlooking the base. In two weeks of bitter, uphill fighting, the Marines killed 940 NVA at a cost of 125 dead. In July 1967, the action shifted farther to the east, where the 9th Marines blocked another invasion attempt and the enemy retreated after losing almost 1,300 men. The direct assaults across the DMZ had resulted in heavy enemy losses. As a result, the NVA shifted to heavy artillery, rocket, and mortar attacks along the northern border. The focal point for much of this fire was Con Thien artillery fire base. The Marines there endured heavy shelling throughout the late summer and the fall of 1967.

The Tet Offensive and Withdrawal

On January 31, 1968, the North Vietnamese unleashed their biggest offensive of the war. Taking advantage of the Tet (Vietnamese Lunar New Year) holiday season and the poor weather associated with the northeast monsoons, the VC infiltrated some 68,000 troops and insurgents into the major population centers of South Vietnam. The allies responded quickly, drove the invaders from the cities and in three weeks killed 32,000 enemy troops. Prolonged fighting continued in Saigon and Hue, where die-hard remnants held out for several weeks. In Hue, a near division-size NVA force occupied the city and its Citadel, which encompassed the old imperial grounds. Marine, Army, and South Vietnamese troops, including the 1st and 5th Marines, cleared the southern half of the city in brutal street fighting and then turned to the walled Citadel. This was the Marines’ first combat in a built-up area since fighting in Seoul during the Korean War. On February 24, the enemy flag, which had flown over the Citadel for 24 days, was ripped down and the last enemy pockets of resistance collapsed the next day. The battle cost the NVA 5,000 men.

While the fighting raged in Hue, the men of the 26th Marines (from the reactivated 5th MarDiv) were engaged in a different type of struggle at Khe Sanh. Beginning in late 1967, two NVA divisions, the 325th and the 304th, had invested that garrison and on January 21, 1968, unleashed their first attack. Marines reinforced the three organic battalions of the 26th Marines with the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, and the 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion, setting the stage for one of the most dramatic battles of the war. For two and a half months, the Khe Sanh defenders fought off enemy ground attacks and weathered daily artillery, rocket, and mortar attacks. During the siege, U.S. aircraft dropped more than 100,000 tons of bombs on the hills surrounding Khe Sanh, while Marine and U.S. Army batteries fired in excess of 150,000 artillery rounds. Literally blown from their positions, the NVA withdrew in the face of a combined Marine, Army, and South Vietnamese task force, advancing toward Khe Sanh from the east. All told, the NVA lost about 3,000 men during the two operations, although some estimates of enemy dead ran as high as 12,000.

On March 31, 1968, President Johnson made a television address to the Nation, during which he announced that he was limiting the U.S. air strikes against North Vietnam. This action eventually led to peace talks in Paris, which began on May 13, 1968. Even with talks underway, the fighting continued in South Vietnam. Additional reinforcements also arrived in I Corps: the 1st Air Cavalry Division, elements of the 101st Airborne Division, and the 27th Marines all came under III MAF control, totaling 163,000 American troops, more than any Marine Corps command in history.

During early 1969, President Richard M. Nixon announced that 25,000 U.S. troops would depart South Vietnam, beginning in July 1969. By mid-November, the 3rd MarDiv had redeployed to Okinawa. This withdrawal movement continued into mid-1970 when the 1st MarDiv departed Vietnam, leaving only a reinforced regiment in place. The Army’s XXIV Corps replaced III MAF in March 1970 and assumed operational control of the remaining American troops in I Corps. Slightly more than a year later, all Marines had returned to their permanent bases except for small numbers remaining to complete the final administrative and logistical tasks.

Returning to Readiness

Mayaguez Incident

On May 12, 1975, just two weeks after the evacuation of Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War, the unarmed American container ship Mayaguez was seized by a Cambodian gunboat and taken to the Cambodian offshore island of Koh Tang. Since no amphibious units were near the area, Marine units from Okinawa were airlifted to Utapao air base in nearby Thailand for an assault on the ship and island using U.S. Air Force helicopters. Recapture of the ship proceeded on May 15 when Marines boarded and seized the ship, which they found had been recently abandoned.

At the same time, a 210-man raiding force of Marines from Company G, 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines assaulted the island of Koh Tang, where it was believed the American crew was being held. Landing from Air Force CH-53 and HH-53 helicopters, the assault encountered heavy ground fire. The Marines fought on the island until their evacuation on the night of May 16. Shortly after the assault landing, the crewmembers of Mayaguez were picked up by a U.S. Navy ship and were able to sail away while the fighting on Koh Tang Island was still going on. Casualties in this operation were heavy, with 11 Marines killed, 3 Marines missing, and 50 other servicemen wounded. Three of the 15 helicopters used in the operation were shot down, and 10 others received battle damage.

Marines in Lebanon, Grenada and Panama—1982–89

Marines returned to Lebanon on August 25, 1982, with the landing of roughly 800 men of the 32nd Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU) to join a multinational peacekeeping force. The other troops participating were 400 French and 800 Italians, and the mission of the force was evacuation of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) guerrillas who were under siege in Beirut by Israeli forces. The evacuation was completed on September 10, but shortly afterward the MAU returned, and for the next 16 months, a MAU was maintained in Beirut on rotation. Marines experienced a variety of both combat and noncombat situations. A suicide truck packed with explosives attacked the BLT 1/8 headquarters building at the Beirut International Airport killing 241 Americans and wounding 70 others on October 23, 1983. After civil strife worsened, American civilians and other foreign nationals were evacuated by helicopter on February 10–11, 1984, leaving a residual force behind to protect the U.S. Embassy. The 22nd MAU completed the last such deployment on February 26, 1984.

Following the assassination of the Prime Minister and overthrow of the government of Grenada, U.S. intervention was requested by neighboring Caribbean nations. On October 25, the Marines of the 22nd MAU made helicopter and beach landings to seize Pearls Airport and rescue several hundred American students attending the local medical college. Simultaneous landings by U.S. Army airborne troops were aimed at seizure of a second larger airfield in the south of the island. 22nd MAU accomplished its mission, while capturing large quantities of weapons and ammunition, as well as large numbers of Cubans and Grenadian insurgents.

Instability in Panama threatened the safety of Americans there as well as international use of the Panama Canal. Further complicating the issue were American criminal charges of narcotics smuggling against the Panamanian dictator. On December 20, 1989, five days after a Panamanian gunman killed a Marine officer, the U.S. Army inserted a combat force to preserve the Panama Canal Treaty and apprehend the dictator. Marines from Company K, 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines, and Company D, 2nd Light Armored Infantry Battalion, also deployed to provide security for defense installations, participated in the Army attack on the Panamanian Defense Force (PDF). Marines were tasked with protecting the Pacific entrance to the canal, establishing roadblocks, and apprehending PDF members. By the end of the first day, Marines had seized several PDF compounds, apprehended 1,200 Panamanians, and confiscated more than 550 weapons.

Operations to Liberate Kuwait: Desert Shield and Desert Storm

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded neighboring Kuwait. The American government anticipated a possible Iraqi attack on Saudi Arabia, which led President George H. W. Bush to order U.S. forces to the region. This began one of the most rapid overseas buildups of an American force in history. Much of the 1st MarDiv stood in the Saudi desert by the end of the month. Other elements of the I and II MEFs followed through February 1991. In addition, the President authorized the first large-scale activation of Reserve units since the early 1950s.

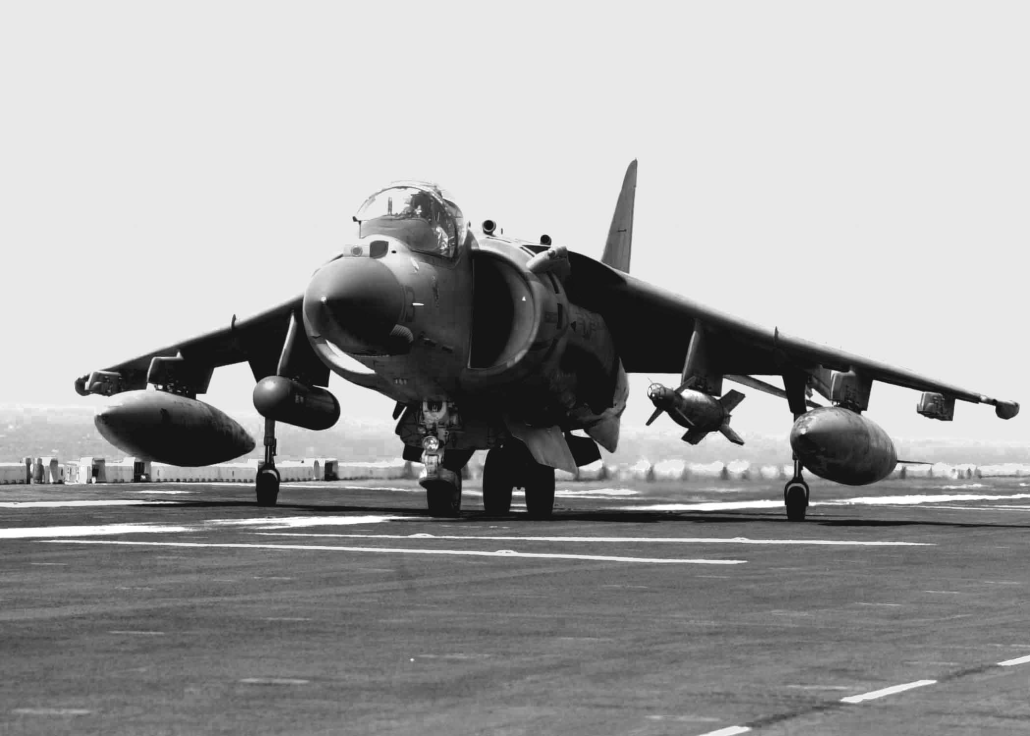

With forces in place to defend Saudi Arabia, Kuwait became the focus of the United States and an American-led coalition of nations. On January 16, the allies launched air strikes that began a five-week strategic and tactical air campaign. Allied air forces quickly achieved and maintained air supremacy throughout the theater. Marine Corps F/A-18 Hornets, A-6E Intruders, AV-8B Harriers, and EA-6B Prowlers participated in the campaign. (See Figure 2-18.) In the fourth week, even Marine C-130s took an offensive role, dropping several fuel-air-explosive bombs on tactical targets.

Marine ground forces—two divisions and service support of a large I MEF were positioned on the border south of Kuwait during the air campaign. The 1st MarDiv held positions near the Persian Gulf, while the 2nd MarDiv was farther inland. The 4th and 5th MEBs and the 13th MEU remained on board amphibious shipping in the gulf. After assisting in the repulse of the January 29 Iraqi attack into the Saudi town of Khafji, the Marines attacked with their two divisions on the morning of February 24. They quickly breached the mined defensives and engaged the Iraqis in ground combat.

The two MarDivs and combined Arab forces on either flank carried out a supporting attack, fixing the Iraqis in place while U.S. Army and allied forces were to move into Iraq west of Kuwait to isolate and surround the Iraqi invasion force. Each attack caused the Iraqis to crumble; however, President Bush ordered a ceasefire on February 28 with the 2nd MarDiv pursuing Iraqi units near the city’s western suburb, and the 1st MarDiv consolidating its gains near the international airport to the south of the city. A formal truce took place shortly afterward. Twenty-three Marines died in action during the four-day ground war.

More Stabilization Operations

In the aftermath of the Gulf War, the 24th MEU deployed to northern Iraq to assist refugee Kurds, a minority group in Iraq and Turkey. The Marines served in a 10-nation force that provided humanitarian relief. It was one of several such military operations other than war (MOOTW) that, in addition to the Iraqi campaign, characterized the use of American forces in the 1990s.

In August 1990, as Marines were preparing to deploy to Southwest Asia, the 22nd MEU landed in the African nation of Liberia, where political instability was threatening the security of foreign nationals. They established a security zone at the U.S. embassy in Monrovia, and evacuated 1,705 foreign nationals. The 22nd MEU was relieved by the 26th MEU, which acted as a peacekeeping force and helped transport relief workers until reembarking on amphibious shipping in January 1991. Also in January, the 4th MEB landed in Somalia to evacuate more than 400 foreign nationals from that nation’s capital, Mogadishu.

While returning from the Iraqi campaign, the 5th MEB provided humanitarian relief after a major typhoon decimated much of Bangladesh in south Asia during May 15–19, 1991. The next month, the 15th MEU joined reinforcements from Okinawa in the Philippines to help provide relief following the volcanic eruption of Mount Pinatubo.

In May 1992, the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines and the 3rd Light Armored Infantry Battalion provided support to civilian law-enforcement agencies during riots in Los Angeles. The Marines, as well as national guardsmen, provided security but did not directly participate in police activities, in accordance with American law.

In June 1992, the 9th Engineer Support Battalion and the 3rd Recon Battalion helped provide drought relief to the Micronesian island of Chuuk. Two months later, the 1st MEB supported typhoon victims in Guam. The action was followed shortly by domestic hurricane disasters in Dade County, Florida, and Kauai, Hawaii. The 1st MEB supported victims in Kauai from August to October 1992, while about 1,000 Marines from various commands supported hurricane victims in Florida.

The Marine Corps played a key role in one of the largest humanitarian operations in Somalia. On December 9, 1992, the 15th MEU landed in Mogadishu to take control of the massive famine relief effort, followed by reinforcements from I MEF. After a successful performance, they turned over control of the operation to the United Nations five months later.

Though immediate relief needs were met in Somalia, the political situation there slowly deteriorated during the rest of 1993 and 1994. Marines played a minor role in the U.N. operation during those months, but in March 1995, they were called back to center stage by President Bill Clinton. The 13th MEU, with elements of 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines and 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, protected the extraction of multinational peacekeepers and recovery of U.S. equipment and weaponry. Marines engaged Somalis in light fighting during the 73-hour operation. The most significant aspect of the encounter was the Marine use of nonlethal weapons, including sticky foam and stun grenades. It was the Corps’ first employment ever of such weapons.

Throughout 1994, Marines participated in joint Caribbean Sea operations to prevent Haitian and Cuban boat people from reaching the United States illegally. Marines also maintained separate refugee camps for Haitians and Cubans at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. After a military coup in Haiti, President Clinton demanded that the Haitian military leaders return governmental control to that nation’s democratically elected officials. American forces, including Marines, deployed as peacekeepers during the transfer of power.

On April 20, 1996, a reinforced rifle company from the 22nd MEU was airlifted into Monrovia, Liberia, to assist with the evacuation of American and designated foreign citizens once again because of decreasing stability in that country. Operations in Africa continued sporadically through July 1997, when 22nd MEU evacuated more than 2,500 civilians from Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Conflict in the Balkans

With United Nations peacekeepers unable to stabilize a war between the newly independent states of the former Yugoslavia, NATO established a no-fly zone in 1993 with the intention of preventing Serb aircraft from attacking or supporting attacks in Bosnia. Marine F/A-18 Hornets and EA-6B Prowlers participated in patrols to enforce that no-fly zone. Marine pilots also participated in air strikes during 1994 and 1995, including a recovery operation by 24th MEU rescuing a downed U.S. Air Force pilot.

In June 1996, VMU-1, a Marine unmanned aerial vehicle squadron, deployed to Bosnia to provide reconnaissance support for the American elements of the NATO peacekeeping force. In June 1999, 26th MEU went ashore as the first American forces into Kosovo, again on NATO peacekeeping duty. The Marines remained in Kosovo for six weeks, before handing the mission off to Army forces, and redeploying to amphibious shipping. Such Balkan activities subsided at the end of the century, but Marines continue to deploy and train in the region.

Conflict in Southwest Asia

The 2001 attack on two U.S. cities by terrorists led to the successive deployment of U.S. forces to Afghanistan, the initial terrorist base, and then the widening of the prosecution known as the “Global War on Terror” into Yemen and Somalia and the epic invasion of Iraq in 2003. These measures produced crushing military defeats of the enemy in each case. However, they also led to long-term campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan to occupy, pacify, and conduct security and stabilization operations in order to establish native governments that would lead their nations into the peaceful international community.

The Marine Corps contribution for the campaign in Afghanistan, beginning in October of 2001, initially consisted of a two MEUs, under Brigadier General James N. Mattis, launching combat forces and supporting aviation hundreds of miles inland to envelop the southeast portion of the country around the cultural center of Khandahar. These actions, combined with the U.S. assisted antigovernment forces of Afghans in the north, caused the scattering of the Taliban leaders and the terrorist bands they had sheltered. A U.S. approved provisional government took office in December, and the pacification program for that country continues.

Such an unusual campaign, resembling the Caribbean antibandit operations of the early 20th century, remained small scale compared to the Marine Corps contribution to the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), beginning in March 2003, saw Marines comprising half of the initial U.S. assault forces and a third of the overall forces in the initial campaign. The I MEF employed the 1st MarDiv and a regimental task force of 2nd MarDiv with a reinforced 3rd MAW and 1st Force Service Support Group to sweep into Southeastern Iraq, detaching the British Army and Royal Marine contingents and a Marine MEU to take Basra and the Faw Peninsula. Continuing onward, Marines shattered the Iraqi army in a fast-moving battle and pursuit between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers past Kut and into Baghdad from the south. As the Iraqi government and military collapsed, the Marine Corps and Army forces secured Baghdad, while more Marines swept northward to prevent any consolidation by Iraqi remnant forces.

Marine Corps forces then undertook the occupation of south-central Iraq between Baghdad and Basra for another six months while the United Nations sorted out an international coalition to relieve U.S. forces. In the end, a continuing U.S. presence became necessary, and I MEF returned to Iraq in February 2004 after a brief absence. A continuous occupation of western Iraq by Marine Corps Forces (I and II MEF in rotation) ensued.

More than 20,000 Marines and sailors of I MEF took up their new positions for the 2004 campaign. The combat operations of the campaign beginning in 2004 have seen major urban battles in the cities of Fallujah and Ramadi counterinsurgency operations, both rural and urban, all over western Iraq, and a continuing effort to rebuild, protect, and nourish the native society and economy of a former enemy nation.

Those mission successes and achievements did not come without cost. During the campaign of 2004 to 2005, some 500 Marines of Multinational Force-West lost their lives while serving in Iraq with thousands more wounded—many grievously—in combat. Since March 20, 2004, elements of I and II MEF (augmented by the rest of the active and Reserve establishment) provided continuous presence in Iraq. Throughout these rotations, Marines have demonstrated the same great courage in battle as did those cited at the beginning of this chapter. Marines have shown remarkable stamina over months and later years, maintaining unshakable honor tested in the most complex environment imaginable. It represents immeasurable personal sacrifice and that of Marine Corps families.

These most recent actions illustrate the continuity in the Marine Corps story. In every clime and place Marines have stood vigil ashore and afloat. Readiness and amphibious expertise remain our hallmark. As long as our Nation possesses and exercises command of the seas, Marines will form its cutting edge.

Traditions

To continue from the beginning of the chapter, traditions obviously have come to us from the generations of Marines who preceded us. As we observe them, we do honor to our predecessors and ourselves. Among the more significant are:

Semper Fidelis (“Always Faithful”). The motto of the Corps, adopted about 1883. Before that, there had been three mottos, all traditional rather than official: Fortitudine (“With Fortitude”), “By Sea and by Land,” and “From the Halls of the Montezumas to the Shores of Tripoli.”

“The Marines’ Hymn.” The hymn of the Marine Corps, as contrasted with “Semper Fidelis,” the Corps march. Every Marine knows the words of “The Marines’ Hymn,” the oldest of the official songs of the U.S. Armed Services and will sing them at the drop of a field hat.

First on foot, and right of the line. Marines form at the place of honor—at the head of column or on right of line—in any naval formation. This privilege was bestowed on the Corps by the Secretary of the Navy on August 9, 1876.

“First to fight.” The slogan has appeared on Marine recruiting posters since World War I.

Marine Talk and Terminology. Because of our naval origins, we speak in a combination of soldier and sailor. Thus floors, walls, ceilings become “decks,” “bulkheads,” and “overheads.” The water fountain is a “scuttlebutt,” and the rest room, the “head.” Never feel self-conscious about using Marine terms—especially the prescribed and traditional “Aye, aye, Sir (or Ma’am).”

“Tell it to the Marines!” Marines go everywhere and see everything, and if they say it is so, it is to be believed. This yarn is an old one, found in print as early as 1726.

Military Courtesy: The Finer Touch of Marine Culture

Courtesy is the accepted form of politeness among civilized people. Courtesy smoothes the personal relationship among individuals in all walks of life. A good rule of thumb might be the golden rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” The Marine remains an absolute model of military courtesy to all other services, as is the case with fighting spirit.

The Salute

The most important of all military courtesies is the salute. This is an honored tradition of the military profession throughout the world. The saluting custom goes back to earliest recorded history.

It is believed to have originated in the days when all men bore arms. In those days, warriors raised their weapons in such a manner as to show friendly intentions. They sometimes would shift their weapons from the right hand to the left and raise their right hand to show that they did not mean to attack.

Just as you show marks of respect to your seniors in civilian life, military courtesy demands that you show respect to your seniors in the military profession. Your military seniors are the officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) senior to you. Regulations require that all officers be saluted by their juniors and that they return such salutes. In saluting an officer, a junior Marine is formally recognizing the officer as a military superior and is reaffirming the oath to obey the order of all officers appointed over the Marine. By returning the salute, the senior officer greets the junior as a fellow Marine and expresses the appreciation of the junior’s support. Enlisted personnel do not ordinarily exchange salutes.

The Hand Salute

Today, the salute has several forms. The hand salute is the most common. When a salute is executed, the right hand is raised smartly until the tip of the forefinger touches the lower part of the headgear. Thumb and fingers are extended and joined. The palm is turned slightly inward until the person saluting can just see its surface from the corner of the right eye. The upper arm is parallel to the ground with the elbow slightly in front of the body. The forearm is inclined at a 45-degree angle, hand and wrist in a straight line. Completion of the salute is executed by dropping the arm to its normal position in one sharp, clean motion. (See Figure 2-19.)

Some General Rules

- When meeting an officer who is either riding or walking, salute when six paces away in order to give time for a return of your salute before you are abreast of the officer.

- Hold the salute until it is returned.

- Accompany the salute with “Good morning, Sir/Ma’am,” or some other appropriate greeting.

- Render the salute but once if the senior remains in the immediate vicinity. If conversation takes place, however, salute again when the senior leaves or when you depart.

- When passing an officer who is going in the same direction, as you come abreast of the officer, on the left side if possible, salute and say, “By your leave, Sir/Ma’am.” The officer will return the salute and say, “Carry on” or “Granted.” You then finish your salute and pass ahead of the officer.

- Members of the naval service are required to render a salute to officers, regular and Reserve, of the Navy, Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and to foreign military and naval officers whose governments are formally recognized by the government of the United States.

- Upon the approach of an officer superior in rank, individuals of a group not in formation are called to attention by the first person noticing the officer, and all come smartly to attention and salute.

Do Not Salute:

- If you are engaged in work or play unless spoken to directly.

- If you are a prisoner. Prisoners are denied the privilege.

- While guarding prisoners.

- Under battlefield conditions.

- When not wearing a cover.

- With any item in your right hand.

- With a pipe or cigarette or other items in your mouth.

- When in formation, EXCEPT at the command “Present Arms.”

- When moving at “double time”— ALWAYS slow to a normal walk before saluting.

- When carrying articles in both hands, or otherwise so occupied as to make saluting impractical. (It would be appropriate, however, to render a proper greeting, e.g., “Good evening, Sir/Ma’am.”)

- In public places where obviously inappropriate (theaters, restaurants, etc.).