Equipping Marines better and faster: a proactive approach

The new administration’s call for a revitalized military demands a fresh look at defense acquisition reform. The DOD has wrestled with the complexities of acquiring and fielding advanced military capabilities for decades, generating a mountain of studies, reports, and recommendations in the process. Yet, a crucial question remains: how can we navigate this complex landscape to best equip Marines for the 21st-century battlefield? This question takes on even greater urgency as the character of warfare continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace, driven by technological breakthroughs, the proliferation of advanced weaponry, and the emergence of new domains of conflict, such as cyberspace and space. Our role as the stand-in force within the acquisition weapons engagement zone provides us with a unique perspective on balancing reform needs with crisis response. Every decision we make hinges on one essential question: will it result in sustainable, superior capabilities delivered to Marines faster?

This question drives acquisition professionals at the Program Executive Office, Land Systems (PEO-LS). Tasked with equipping the Marine Corps with the groundbased weapons systems and equipment necessary for success in modern warfare, PEO-LS occupies a critical position within the defense acquisition ecosystem. As the stand-in force in the acquisition world, PEO-LS must constantly balance the need for modernization and innovation with the urgency of delivering capabilities to Marines rapidly and efficiently.

The PEO-LS recognizes that success in this challenging arena requires strong partnerships across the Marine Corps and the broader DOD. The organization collaborates closely with entities like the Deputy Commandants for Capabilities Development and Integration and Programs and Resources, Marine Corps Systems Command, and fellow program executive offices to ensure aligned efforts and a cohesive approach to acquisition reform. These partnerships are essential for breaking down bureaucratic silos, fostering shared understanding, and promoting unity of effort across the acquisition enterprise.

Evolutionary Versus Revolutionary Reform: Forging the Optimal Path

The debate surrounding defense acquisition reform often hinges on the appropriate balance between evolutionary and revolutionary change. Proposals for reforming the Defense Acquisition System span a broad spectrum, from evolutionary tweaks within existing frameworks to revolutionary overhauls aimed at redefining processes and structures. This debate is not merely academic; it has real-world implications for the ability of the U.S. military to maintain its technological edge and prevail in future conflicts.

Evolutionary reforms target incremental improvements to existing processes and structures within the traditional pillars of requirements, resources, procurement, and sustainment. The 2020 Adaptive Acquisition Framework, with its emphasis on tailored pathways for different types of acquisition programs, exemplifies this approach. However, as highlighted by a recent Government Accountability Office assessment, these efforts have yet to significantly reduce the average delivery time for weapon systems.1 While such reforms can generate positive results, they often fail to keep pace with the rapid technological advancements and evolving character of warfare. Critics argue that evolutionary reforms, while well-intentioned, often amount to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic: they may improve efficiency at the margins, but they fail to address the systemic issues that plague defense acquisition.

Revolutionary reforms demand a fundamental reimagining of the Defense Acquisition System. These proposals advocate for disruptive changes to processes, organizational structures, authorities, and even the underlying culture of defense acquisition. Proponents of revolutionary reform argue that the current system, rooted in a bygone era of industrial-age warfare, is simply not equipped to deal with the complexities and challenges of 21st-century defense acquisition. They call for a fundamental shift in mindset from a culture of risk aversion and bureaucratic inertia to one that embraces innovation, experimentation, and rapid iteration.

Three recent efforts are notable. First, the Atlantic Commission report on the Commission on Defense Innovation offered many proposals that adopt the private sector’s rapid innovation best practices.2 The Commission also proposed modernizing acquisition and budgeting processes to foster increased collaboration with nontraditional companies to get advanced technology to warfighters sooner. Second, the NDAA FY 2022 Sec. 1004 Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) Reform final report recommended that the DOD should adopt a new resourcing system.3 The proposed Defense Resourcing System, in the commission’s view, would preserve the strengths of the current PPBE process while also better aligning strategy with resource allocation and allowing the DOD to respond more effectively to emerging threats and technological advances. Finally, a recent Bloomberg Strategic Edge study, chaired by the former Commandant, Gen Berger, highlighted the urgency of rebuilding the industrial base, using non-traditional innovators, and unlocking private capital to accelerate the fielding of emerging technologies.4 Differing from the other studies, this report recommended the DOD carry out these acceleration efforts by divesting fifteen percent of its budget for some of its aging legacy systems to fund a new parallel track for fielding high-technology capability quickly and at scale.

These diverse yet interconnected proposals share common threads: a focus on accelerating innovation, streamlining resource allocation, embracing organizational agility, and fostering closer collaboration with the private sector. The challenge lies in determining which specific reforms, and to what degree, will deliver the greatest benefit for the Marine Corps and the broader defense enterprise. This requires careful analysis, a willingness to experiment, and a commitment to continuous learning and improvement.

PEO-LS: A Dual Approach to Driving Transformation

The PEO-LS recognizes that successful reform requires both strategic vision and tactical execution. The organization actively implements strategic revolutionary changes while simultaneously driving tactical innovations within the existing framework. This dual approach enables PEO-LS to pursue both incremental improvements and more transformative changes, maximizing its impact on the defense acquisition process.

Strategic Reorganization and Process Optimization

The PEO-LS has undertaken a series of organizational realignments designed to enhance efficiency and better align its internal structure with the evolving needs of the Marine Corps. For example, we have reorganized program offices to enhance alignment and efficiency, merging key capability areas to better support Force Design aims. Notable examples include:

- MAGTF Command and Control (C2): By combining ground and aviation command and control programs, we are developing an integrated, scalable MAGTF Command and Control solution. This initiative ensures interoperability across naval, joint, and coalition forces.

- Intelligence and Cyber Operations: We have merged intelligence and cyber programs to use their unique network warfare capabilities, enhancing our ability to address emerging threats.

These integrated capability areas streamline decision-making processes, reduce redundancies, and foster greater synergy between related programs. This approach recognizes that the nature of warfare is increasingly interconnected, requiring a more integrated and holistic approach to capability development.

These examples show how we are continuously implementing acquisition reform while working within the bounds of the current process. We are stretching those bounds by adapting strategic-level changes, such as assigning several of our program managers to also act as capability acquisition managers, looking beyond their specific programs to see how they can improve key capability areas supporting Force Design outcomes, including integrated C2, counter unmanned systems, and integrated air and missile defense.

Recognizing that overly bureaucratic processes can stifle innovation and slow down acquisition timelines, PEO-LS has implemented a range of process improvements aimed at reducing administrative burdens and streamlining procurement activities. These efforts include eliminating redundant tasks, automating workflows, and delegating responsibilities to the lowest appropriate level. The PEO-LS has placed a particular focus on reducing procurement administrative lead time, particularly within the contracting process, where delays can significantly impact program schedules. This focus on streamlining processes is essential for enabling the rapid acquisition of emerging technologies, which often have shorter lifecycles and require a more agile approach.

Tactical Success: Rapidly Fielding Advanced Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (CUAS) Capabilities

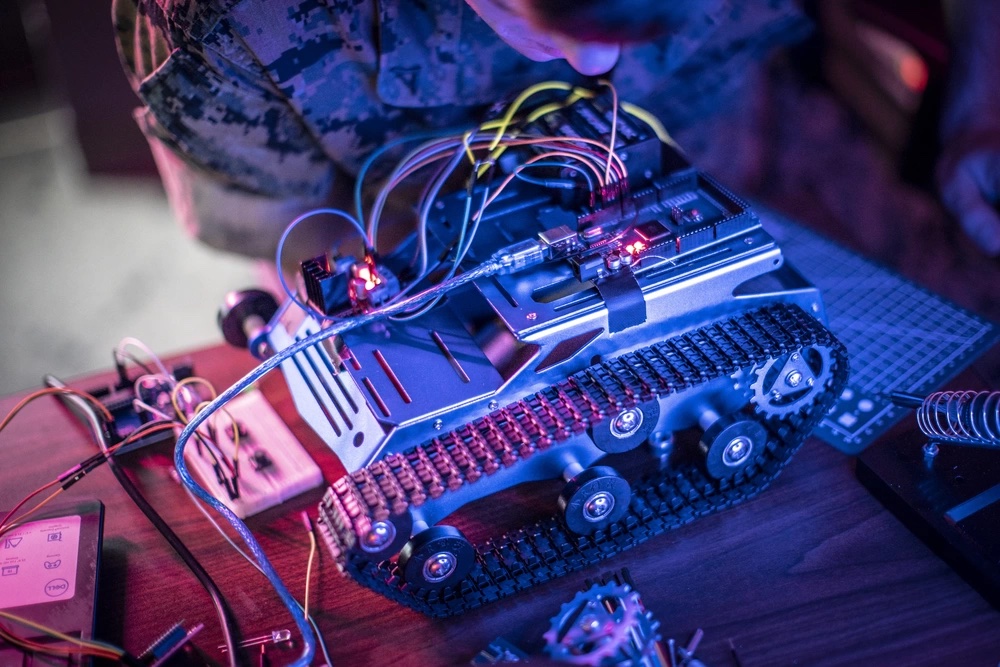

Blending strategic-level revolutionary changes (such as the FoRGED Act or Gen Berger’s “Blueprint for Defense Innovation”) to the tactical changes, the Marine Corps acquisition professionals have and will continue to spearhead improved capability delivery. The results are impressive across several portfolios, but none more so than CUAS. Just five years ago, the only CUAS capability any Marine formation had was a Stinger missile and a Mark 1 Mod 0 eyeball for detection. This year, PEO-LS’s Ground-Based Air Defense Program will complete the development or fielding of five programs of record and one urgent capability acquisition: MADIS, L-MADIS (replacing a Joint Universal Needs capability), installation defense of small CUAS (replacing a Joint Urgent Operational Need system), Medium Range Intercept Capability, and organic CUAS for dismounted formations.5

These successes highlight the importance of close collaboration between PEO-LS and key partners such as the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab and the Deputy Commandant for Capabilities Development and Integration. By working together, these organizations have successfully begun to better bridge the valley of death that often hinders the transition of promising technologies and capabilities from development to deployment, ensuring that Marines receive the tools they need without delay. This collaborative approach is essential for overcoming the stovepipe nature of traditional defense acquisition and fostering a more integrated and responsive approach to capability development.

The Road Ahead: Embracing Continuous Improvement and Empowering the Workforce

While PEO-LS has made significant strides in advancing acquisition reform, the journey continues. The organization recognizes that reform is not a destination, but rather a continuous process of adaptation, innovation, and improvement. In a rapidly changing security environment, the defense acquisition system must be able to adapt and evolve to meet new challenges and seize new opportunities.

To guide its ongoing efforts, PEO-LS must continuously ask critical questions and challenge the status quo:

- How can we better integrate emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and directed energy, into existing and future acquisition programs? The PEO-LS must be proactive in identifying and evaluating emerging technologies, and in developing innovative acquisition strategies that enable the rapid fielding of these game-changing capabilities.

- How can we foster deeper and more impactful collaboration with the private sector, particularly with non-traditional defense companies that bring new ideas and innovative solutions to the table? The PEO-LS must be proactive in engaging with these nontraditional players, leveraging their expertise and innovation to deliver cutting-edge capabilities to the warfighter.

- How can we strike the right balance between the need for speed in acquisition, particularly in response to rapidly evolving threats, with the imperative for accountability and responsible stewardship of taxpayer dollars?

The PEO-LS must continue to refine its processes and procedures to ensure that it can acquire capabilities rapidly while maintaining the highest standards of fiscal responsibility and accountability to the American taxpayer.

By continuously asking these questions and engaging in a robust dialogue with stakeholders across the defense acquisition community, PEO-LS ensures that its reform efforts remain relevant, effective, and responsive to the evolving needs of the Marine Corps. This requires a commitment to continuous learning, a willingness to experiment, and a relentless focus on delivering results for the warfighter.

Conclusion: An Unwavering Commitment to Delivering Capabilities and Equipping Marines for the Future Fight

While the journey toward acquisition reform is fraught with challenges, it also presents significant opportunities. Recent workforce reductions will align to process improvements reducing non-value-added tasks. Our optimized workforce remains our greatest asset The PEO-LS acquisition professionals bring unparalleled ability and dedication to the mission, making them well-equipped to implement both strategic and tactical reforms.

At PEO-LS, acquisition reform is not simply an abstract concept or a box to be checked. It represents a fundamental commitment to delivering the best possible capabilities to Marines as quickly and efficiently as possible. As the stand-in force within the acquisition weapons engagement zone, Marine Corps acquisition professionals are best positioned to lead the way in evolutionary and revolutionary acquisition reform efforts. Ultimately, the true measure of success will be our ability to deliver sustainable, superior capabilities to Marines faster. By keeping a steadfast focus on this goal, we can lead the charge in acquisition reform, ensuring the Marine Corps stays at the forefront of innovation and readiness. By staying true to our mission and embracing a culture of continuous improvement, we can ensure that the Marine Corps stays ready and capable in an ever-changing world.

>SES Bowdren is the Program Executive Officer Land Systems, Marine Corps Systems Command.

Notes

1. Government Accountability Office, DOD Acquisition Reform (Washington, DC: December 2024).

2. Whitney M. McNamara, Peter Modigliani, Matthew MacGregor, and Eric Lofgren, “Atlantic Council Commission on Defense Innovation Adoption,” Atlantic Council, January 16, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/atlantic-council-commission-on-defense-innovation-adoption.

3. Commission on Planning, Budgeting, and Executive Reform, Defense Resourcing for the Future (Washington, DC: March 2024).

4. David H. Berger, Kirsten Bartok, Yisroel Brumer, Nathan Diller, Matt George, and Clint Hinote, Strategic Edge (Washington, DC: January 2025).

5. Morgan Blackstock, “PEO Land Systems Fields Advanced Air Defense System to 3D LAAAB,” Marines.mil, December 13, 2024, https://www.peols.marines.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/4000903/peo-land-systems-fields-advanced-air-defense-system-to-3d-laab; and David Jordan, “MRIC Complete Quick Reaction Assessment,” Marines.mil, October 24, 2024, https://www.peols.marines.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3947926/mric-completes-quick-reaction-assessment.