Winthrop Range: The Cradle of Marine Corps Marksmanship

By: Col Dwight Sullivan, USMCR (Ret)Posted on February 15, 2025

Two men lay prone in the Maryland countryside, shouldering Springfield rifles. Each fired a spotting round at a target 200 yards away. The younger man, wearing a Marine Corps uniform, scored a four. To his right was a distinguished gentleman clad in natty civilian attire, a derby atop his silver hair. His first shot hit the bull’s-eye for a score of five. Each man fired another five rounds—all bull’s-eyes.

The date was May 16, 1910. The uniformed Marine was Gunnery Sergeant Peter S. Lund. Born and raised in Denmark, Lund spent most of his 21-year Marine Corps career as a rifle team member, coach and instructor. Although he was a crack shot, Lund was no straight arrow. In 1907, a general court-martial had convicted him of unauthorized absence—one of several offenses for which he was disciplined during his two decades in the Corps. The shooter in civilian clothes was Major General George F. Elliott, the 10th Commandant of the Marine Corps. The two had just placed Marine Corps Rifle Range, Winthrop, Md., into commission.

Located 30 miles south of Washington, D.C., the range was Elliott’s brainchild. The Commandant had a combat Marine’s appreciation of accurate rifle fire. As a captain, he led two companies of Marines augmented by Cuban insurrectos at the Battle of Cuzco Well—a victory that secured the Americans’ presence at Guantanamo Bay at the Spanish-American War’s outset. Elliott was recognized for “eminent and conspicuous conduct under fire” during the operation. The following year, he distinguished himself in combat in the Philippines. Just days after becoming Commandant in 1903, he led a Marine Corps expedition to help stabilize Central America following Panama’s declaration of independence from Colombia. Elliott is the only Commandant since Archibald Henderson to command an expeditionary force in the field. Later in his commandancy, Elliott successfully fought off a proposal to transfer the Marine Corps to the Army.

In his 1907 annual report, Elliott observed that the Marine Corps “suffers from lack of rifle ranges.” He explained that most Marine posts “are in the vicinity of large cities, the surrounding territory of which is thickly settled. The long range and great penetration of the rifle now used, and the longer range and greater penetration of the rifle soon to be issued, make the location of ranges a problem of great difficulty.” Establishing a model rifle range in rural southern Maryland was part of Elliott’s solution.

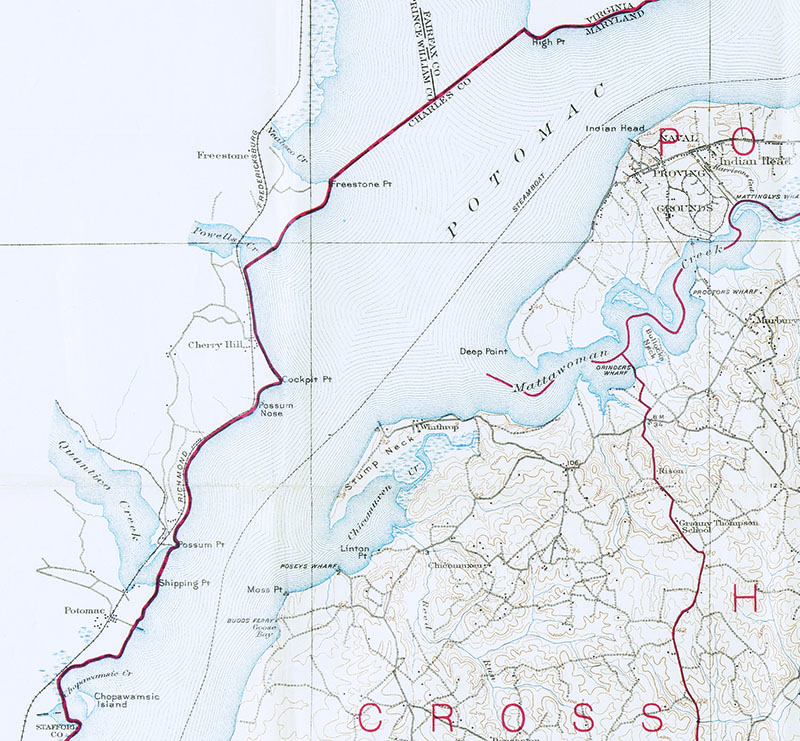

The Navy’s Ordnance Department gave the Marine Corps 1,100 acres on a peninsula jutting into the Potomac River just south of the Indian Head Naval Proving Ground. In 1909, Elliott dispatched a small task force to transform the wooded parcel into a functioning rifle range. Those Marines operated under the leadership of Captain William C. Harllee.

Harllee was one of the Marine Corps’ most capable, colorful and controversial officers of the early 20th century. After being kicked out of both The Citadel and West Point for excessive disciplinary infractions, he enlisted in the Army. He quickly rose to first sergeant, winning accolades for his performance in combat during the Philippine-American War. He was commissioned as a Marine Corps second lieutenant in February 1900. Later that year, Harllee led Marines in combat during the Boxer Rebellion, including participating in the Allied assault on Beijing. But the disciplinary problems that got him expelled from The Citadel and West Point soon reemerged. While assigned in the Philippines as a first lieutenant, Harllee was convicted by a general court-martial and suspended from duty for six months for repeatedly striking a Filipino with a cane. During that same tour, he was suspended from duty for seven days for countermanding his superior’s orders, placed under arrest for 10 days for disrespect toward his commanding officer and suspended from duty for 10 days for engaging in “ungentlemanly behavior.”

Harllee salvaged his Marine Corps career during a successful tour in Hawaii from 1904 to 1906. There, he supervised the construction of a rifle range on an abandoned cattle ranch. After assignments in California, South Carolina and Cuba, Harllee became the Marine Corps rifle team’s captain in 1908. The team thrived under his direction. Harllee was not an elite shooter; he could not calm his nervous energy on the firing line. But he excelled as a teacher and coach. So when Elliott decided to establish a model rifle range in southern Maryland, he tapped Harllee to lead the effort.

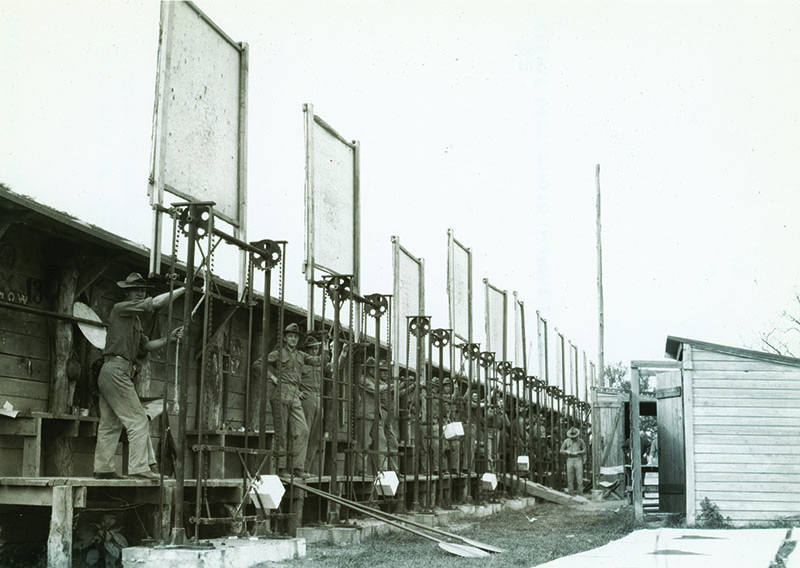

Harllee built the range on a shoestring budget. He, two other officers and about 40 enlisted Marines spent the winter of 1909-1910 living in tents and rough-hewn log cabins as they transformed the wooded and marshy landscape into a fully functional rifle range. Marines experienced in carpentry, plumbing and mechanics were detailed to complete the facility’s infrastructure. To save money, the Marines planted a garden and grew their own produce.

The result was a shooting complex with a variety of firing lines from 200 to 1,000 yards. A hill behind the butts provided a natural backstop. Nevertheless, in July 1910, Harllee received a complaint that a nearby resident was grazed by a stray round from the range. An investigation revealed that bullets were ricocheting off large rocks behind targets near the range’s outer edge. Harllee had the hill behind the butts bulldozed and rocks removed to abate that threat to public safety.

The installation’s original name was “U.S. Marine Corps Rifle Range, Stump Neck, Chickamuxen Post-Office, Md.” Soon after opening, the range was renamed in honor of Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Beekman Winthrop. A blue-blooded descendant of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Winthrop held a series of offices under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. His appointment as governor of Puerto Rico at age 29 led to his nickname, “Boy Governor.” He also had served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury before becoming Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1909.

East Coast Marine barracks from Philadelphia to South Carolina trained at Winthrop. In 1912, roughly 1,800 Marines shot at the range, in addition to 200 members of Army, Navy and National Guard rifle teams. Eventually, every Marine recruit from the Eastern Division was sent to Winthrop to learn to shoot. Winthrop also became the base of operations for the Marine Corps’ successful rifle teams. Marine Corporal George W. Farnham won the Individual Military Rifle Shooting Championship of the United States in 1910, while one of his teammates won the prestigious President’s Match at the National Rifle Association’s tournament. In 1911 and 1916, Marines also won the President’s Match. Even more significantly, the Marine Corps won the National Trophy Team Match in 1911 and 1916 while finishing second in 1915.

Winthrop became the Navy’s hub for its East Coast marksmanship training. Ships undergoing overhauls were required to send detachments of two officers and 20 enlisted men to the range. The Navy also established a three-week course at Winthrop to train its small-arms shooting coaches.

Access to the installation was mainly by water. Marines built a wharf along the Potomac to facilitate the movement of personnel and supplies. The Washington Navy Yard’s tug made a five-hour roundtrip to the range six days a week. Some personnel arrived at Winthrop by taking a train to Cherry Hill, Va., followed by a short ferry ride across the Potomac. The range at Winthrop operated for eight months of the year. As Marine Corps Commandant Major General William P. Biddle reported in 1913, the southern Maryland weather was considered “too severe” for shooting during winter months. The Potomac sometimes became so choked with ice that it was difficult to reach the facility.

Built beside mosquito-infested marshland, Winthrop suffered a malaria outbreak in 1911. The Marine Corps used part of a $20,000 appropriation for range upgrades to install screens on the barracks’ windows and doors. The next year, no malaria cases were reported at Winthrop.

The Navy soon regretted giving the Marine Corps the tract of land that became the Winthrop range. The Bureau of Ordnance repeatedly complained that the range’s location forced the Indian Head Naval Proving Ground to curtail its gunfire due to the proximity of the range’s housing to the line of fire for Indian Head’s naval 12-inch guns. By autumn 1913, the Navy Department was considering an alternate location for its mid-Atlantic rifle range. But when a large portion of the Marine Corps deployed to Veracruz, Mexico, the following year, relocation planning stalled. Winthrop’s facilities deteriorated as needed repairs were deferred amid uncertainty over the range’s long-term future.

Winthrop annually hosted high school boys from Washington, D.C., for a day of shooting. In 1916, the Marine Corps opened the range to all civilians. They could shoot at Winthrop any day but Sunday. A roundtrip boat ride from Washington cost 25 cents. For another 15 cents, civilians could eat lunch at Winthrop’s mess hall. The Marine Corps covered all other expenses, including supplying the civilians with rifles and ammunition.

During the downriver boat ride, Marine noncommissioned officers provided instruction on shooting and scoring while a Navy doctor gave a crash course in first aid. William Harllee—Winthrop’s first commanding officer—served as the Navy Department’s Assistant Director of Target Practice and Engineer Competitions from 1914 to 1918. Throughout that assignment, he championed inviting civilians to shoot at Winthrop as a military preparedness measure. He admonished visitors: “Never offer any man in the military service a tip. It is offensive, and he will not take it. He esteems it a pleasure to welcome you to Winthrop and to make the shooting game attractive to you.” During the summer of 1916, more than 6,000 civilians shot at the range. Among them was Beekman Winthrop’s successor as Assistant Secretary of the Navy: Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In July 1916, Roosevelt hosted a party of dignitaries including Secretary of War Newton Baker on a yacht trip to the range, where the VIPs tested their marksmanship.

The outreach to civilians soon created a controversy. Initially, women were encouraged to participate in the training. A widely published photograph showed a smiling woman poised to fire a machine-gun at Winthrop as another woman stood beside the weapon. In early May 1916, however, Headquarters Marine Corps banned women from shooting at Winthrop and then barred them from the installation entirely. Those decisions generated considerable resentment among the shooting clubs that regularly visited the range.

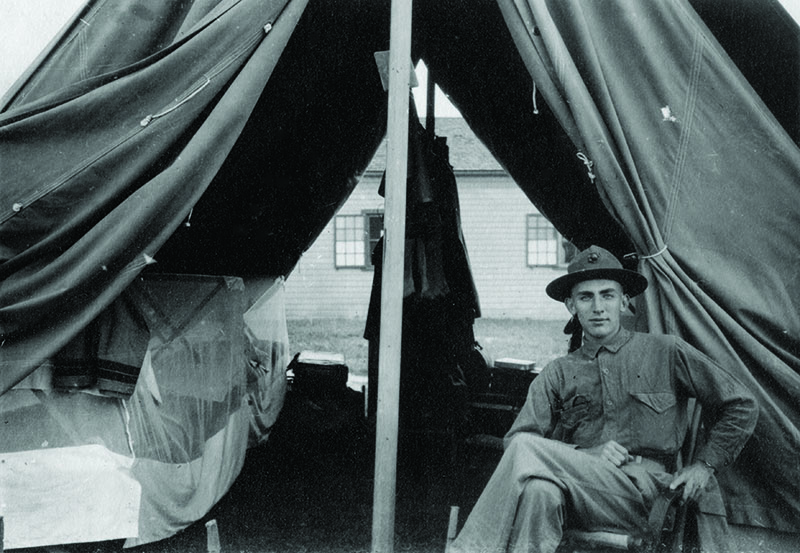

The United States’ entry into World War I on April 6, 1917, precluded civilian use of the range that year. In 1914, the Marine Corps had established a “student camp” at Winthrop as a training ground for newly commissioned Marine second lieutenants with no prior military experience. The program ballooned as the Marine Corps brought a huge influx of civilians—many of them prominent college athletes—into its brotherhood of officers at the start of World War I.

Karl S. Day, a future Marine Corps Reserve general officer, was typical of the second lieutenants who arrived at Winthrop in June 1917. He had recently graduated from Ohio State University, where he captained the track team. Day and his fellow lieutenants initially slept on cots in a wooden barracks. “The heat and mosquitos,” Day wrote “are something awful.” Mosquito netting was issued to protect the lieutenants from Winthrop’s ubiquitous bloodsuckers. The range was so overcrowded that in mid-July, the lieutenants’ barracks was converted into a mess hall. The lieutenants moved into four-man tents. Heavy rain followed, dampening the lieutenants’ canvas-covered belongings.

While the lieutenants were at Winthrop, first call sounded at 6 a.m. every day but Sunday, followed by reveille at 6:10 a.m. The newly commissioned officers assembled at 6:20 a.m. Breakfast was served from 7 a.m. to 8 a.m. Training occupied the lieutenants until a lunch break from 12:15 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. and then resumed in the afternoon except on Saturdays. The lieutenants’ training included classroom instruction, drill, shooting and pulling butts. Dinner was served at 6 p.m. Meals cost the lieutenants $1 a day. They often supplemented their rations by purchasing ice cream cones, pies, chocolate or cakes from the installation’s exchange. Entertainment at the remote facility was limited to movies shown three nights a week. Quarters sounded at 9:45 p.m. and Taps at 10 p.m.

After completing their marksmanship instruction at Winthrop, the lieutenants continued their training at the sprawling new Marine Corps base at Quantico. The Winthrop range soon followed the lieutenants across the Potomac. In autumn 1917, the Marine Corps shut down Winthrop, dismantling the facility’s equipment and moving it to a newly established range at Quantico.

The Winthrop range was in operation for only seven-and-a-half years. But in that short time, it laid the foundation for the Marine Corps’ marksmanship prowess.

Now known as the Stump Neck Annex, the former site of the Winthrop range is home to the Raymond M. Downey Sr. Responder Training Facility. That complex is named in honor of a New York City Fire Department deputy chief who died while heroically responding to the Sept. 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center. Before he was a firefighter, Downey was a Marine. He spent most of his four-year enlistment with 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines.

The Marine Corps’ Chemical Biological Incident Response Force—headquartered nearby at Naval Support Facility Indian Head, Md.—conducts training at the complex named for the fallen firefighter. Marines continue to hone their skills at the site that was once the Winthrop range.

Author’s bio: Colonel Dwight H. Sullivan, USMCR (Ret), is a senior counsel at the Air Force Appellate Defense Division, at Joint Base Andrews, Md., and an adjunct faculty member at the George Washington University Law School. He is the author of “Capturing Aguinaldo: The Daring Raid to Seize the Philippine President at the Dawn of the American Century.”