William Jennison: Continental Marine

By: Bernard Nalty and Truman StrobridgePosted on October 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: We bring you this story from the Leatherneck archives, which covers the seagoing roots of the Corps. Leading up to the Marine Corps’ 250th birthday on Nov. 10, 2025, Leatherneck is dedicating space each month to an article associated with a specific period in the service’s history. This month, we recognize William Jennison, a New Englander who recruited young Marines to fight the British at sea during the Revolutionary War. For more about this time period, see “This Is My Rifle,” and Saved Round.

After six weeks of recruiting duty, William Jennison was thoroughly bored with the Marines. Although only 19 years of age in the spring of 1776, he already had served almost a full year in the Continental armed forces. In April 1775, when the embattled farmers at Lexington fired the shot heard around the world, William, a graduate of Harvard College, was studying law at Providence, R.I. The smoke of this first skirmish of the American Revolution had scarcely cleared when he returned to his home at Mendon, Mass., and enlisted in an infantry company. The company was promptly incorporated in the 13th Massachusetts Regiment, and young Jennison was appointed regimental quartermaster, an assignment which he held until the following spring.

Since Continental troops generally served for a year or less, Jennison left the regiment early in 1776 and returned to Providence and the practice of the law. Here he first learned of the Marines, a military organization that had yet to celebrate its first birthday.

The Continental Marines had been established on Nov. 10, 1775, when the Continental Congress authorized the recruiting of men skilled at fighting on either land or sea. Under the leadership of Samuel Nicholas, the first Marine Corps Commandant, the task of recruiting these men got under way. Among the most difficult problems facing the new Commandant was the organization and training of a Marine guard, usually 20 to 50 men, for each warship in the rapidly expanding Continental Navy. When William Jennison arrived at Providence in April 1776, just such a ship’s guard was being formed to serve in the 32-gun frigate Warren, which was fitting out at the city.

The idea of being a soldier of the sea appealed to Jennison, so he quickly volunteered to serve in the frigate’s Marine guard. Captain Esek Hopkins, the commander in chief of the Continental fleet and skipper of Warren, was so impressed by the young man’s enthusiasm that he urged him to apply instead for a commission in the Marines. Since final approval of the application was expected within a few days, Hopkins directed Jennison to begin recruiting a Marine guard of at least 36 men for Warren. Assisted by a drummer and fifer, Jennison began touring Rhode Island in search of recruits.

At each stop on this journey, he set up a recruiting office at some tavern or inn. The drummer and fifer paraded through town, playing some patriotic tune to attract a crowd. Jennison would then explain what was expected of a Marine—courage, skill with a musket and unquestioning obedience. At each village, he found a few able-bodied men who seemed capable of serving on board ship as well as on land. After administering the oath of enlistment, he would dip into a bag of money given him by Hopkins and hand each of the men a few dollars as an advance against his future pay. By accepting this advance, the recruits bound themselves to the service of the new nation.

As the weeks dragged by, the ranks of the Marine guard were gradually filled, but nothing was heard concerning Jennison’s commission. Overwhelmed by the thousand burdens of conducting the war, Congress was unable to keep up with the flood of applications, and he remained a civilian. What was worse, the work of readying the Warren for battle fell so far behind schedule that Jennison began to wonder if the frigate ever would sail. No wonder, then, that he became bored with his duties.

While the Warren rode listlessly at anchor, the Continental Army was hurriedly throwing up fortifications on Long Island, where General George Washington believed the British would attack. A call went out for volunteers, men who would serve for five months in the ranks of the Continental forces, and once again the men of Massachusetts responded. Another infantry company was formed at Mendon, and among the members of this unit was William Jennison. The fate of the troops assembled to defend New York was, he believed, vital to the success of the Revolution. If Washington’s army were destroyed, the cause of American liberty would perish along with it and the enemy would be able to march unopposed through the colonies. Jennison felt that he had no choice but to turn his Marines, along with the remainder of the recruiting money, over to Hopkins and then to volunteer for five months’ service in the Massachusetts regiment. The Mendon troops marched off to Long Island, arriving there a few weeks before the British struck.

Late in June 1776, within a few days of America’s declaration of independence from Great Britain, enemy warships began gathering off New York. Some 20,000 Red Coats swarmed ashore on Long Island, divided into three columns, and pounced upon the ill-trained Continentals defending the area that has since become the borough of Brooklyn. This opening battle cost the defenders some 400 killed or wounded and 1,000 men taken prisoner. Washington’s remaining forces, among them the regiment in which Jennison was serving, now were isolated at Brooklyn Heights, their backs to the East River. While the enemy was gathering strength to storm this final redoubt, Washington, under cover of darkness, moved 9,000 men with their artillery and supplies across the river to Manhattan Island. Although the British twice attempted to destroy Washington’s command, most of the Americans managed to escape from Manhattan and eventually found temporary refuge in New Jersey.

In November 1776, after five months of campaigning, William Jennison’s enlistment expired. “I left the army at Fishkill,” he wrote in his diary, “with the intent of not being in the land service again.” True to his word, he made his way to Boston where he enlisted on Jan. 14, 1777, as a seaman on the ship Boston, a 24-gun frigate. Then, in February, he finally received his appointment as a lieutenant of Marines and was assigned as second in command of the Boston’s guard detachment.

This cruise of Boston, Jennison’s introduction to warfare at sea, was far from successful. The Boston and the 32-gun Hancock, one of the largest of the Continental frigates, were unable to weigh anchor until late in May. The delay was caused in part by the constant quarreling between the two ships’ captains, Manley of Hancock and McNeill of Boston. “If they are not better united,” reported an agent of the Continental Congress, “infinite damage may accrue.”

Whatever their personal feelings, Manley and McNeill cooperated enthusiastically during their battle with the Fox, a British frigate that mounted 28 guns. Manley struck first, coming alongside the enemy and exchanging salvos broadside to broadside. When the Hancock was clear of the British frigate, the Boston entered the fight, delivering what Capt McNeill called a “Noble Broadside” and forcing the enemy to strike his colors.

As far as Boston was concerned, the remainder of the cruise was a study in frustration. Although a few small merchantmen fell victim to the Yankee frigate, McNeill’s vessel usually ended up fleeing from larger and more heavily gunned British warships. A worse fate, however, lay in store for Hancock. Under the impression that he was being attacked by a 64-gun British man-of-war, Manley surrendered his ship only to discover that the adversary was a mere frigate scarcely larger than his own.

In August, after some 10 weeks at sea, the Boston came about and headed for port. Except for the capture of the Fox, the voyage had been a failure. One of the midshipmen, in an effort to ease the monotony and lessen the crew’s sense of disappointment, organized a raffle. Unfortunately, McNeill learned of this scheme for raising morale and had Jennison place the man in irons on the charge of “selling lottery tickets on board.”

No sooner had the frigate anchored at Boston harbor than the work of refitting got under way. Although Captain Samuel Tucker replaced the quarrelsome McNeill, Richard Palmes continued in command of the Marine guard, with Jennison as his lieutenant.

By December, Boston was almost ready for sea. Since one of the remaining tasks was the finding of replacements for those Marines whose enlistments had expired, Jennison was given $200 and sent out on another recruiting tour. This was more than enough money, for advances against pay were neither large nor freely given. A veteran corporal could expect an advance of no more than $6 upon reenlisting, and a private got less than half that amount. Within 10 days, Jennison had signed on a corporal and three privates.

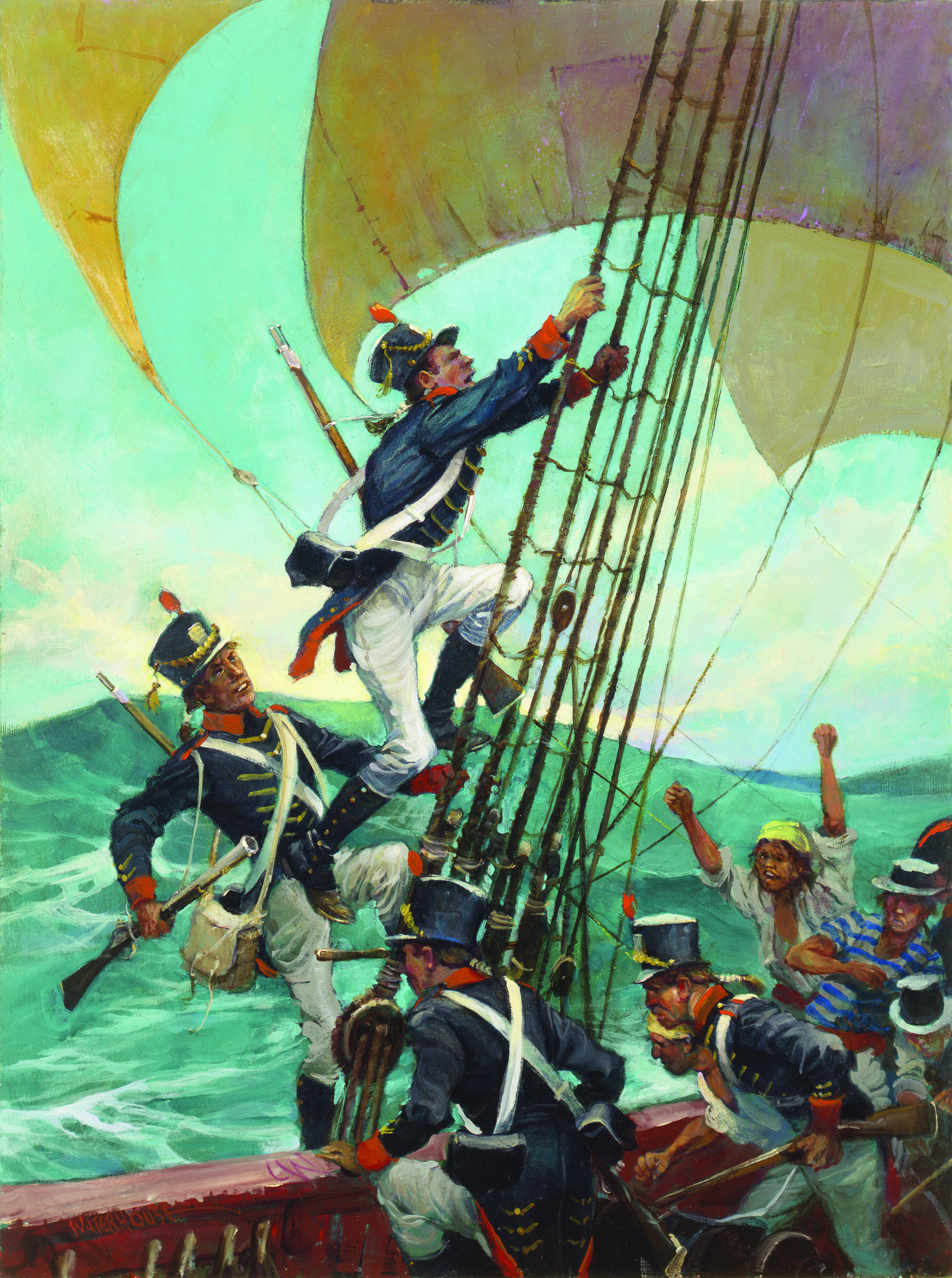

As was the custom, Tucker, upon assuming command of Boston, published a formal order detailing the specific duties of the guard detachment. Although Tucker planned to use the Marines almost exclusively as sentinels, they could perform, with one exception, “any other duty and service on board the ship which they are capable of.” The sole exception was going aloft to handle the sails, a task ordinarily reserved for seamen. In spite of the fact that a Marine “could not be beat or punished” for not showing an “inclination” to go aloft, Capt Tucker nevertheless felt “assured” that “the ambitious will do it without driving.” In other words, the skipper expected the guard to volunteer for work aloft in the event of a storm or other emergency.

Whenever a Yankee frigate went into action, the Marines had two principal jobs—to keep the gun crews at their weapons and to fire from the fighting tops onto the enemy deck. As soon as the crew was called to quarters, each Marine was issued a musket and a cartridge pouch. The sharpshooters then climbed rope ladders to platforms built around the masts some 30 to 40 feet above the deck. These platforms seldom had room for more than two or three men, so the best shots would fire from the prone position while the others reloaded. Those Marines assigned to keep the gunners at their posts also could be employed in boarding parties or could help repel enemy boarders. It did not pay to become “disconcerted or disheartened” during a fight, for anyone who left his post was to be shot immediately.

Once the battle had ended, each Marine was expected to find a piece of cloth, clean his weapon, and return it to his sergeant. Since no musket was returned dirty to the arms chest, the Marines often spent more time cleaning their weapons than they had fighting the battle.

At long last, the Boston was ready for sea, and on Feb. 13, 1778, after the last of the stores had been loaded, “the Honorable John Adams and suite” were piped aboard. Adams had been chosen to serve as a diplomatic representative of the Continental Congress at the French court. Boston was to carry him safely across the Atlantic to this new assignment and, “Capt Tucker,” according to Jennison, “had instructions not to risque the ship in any way that might endanger Mr. Adams.”

The Marines were issued new uniforms, probably in honor of their distinguished passenger. Each man received a white waistcoat, white knee length breeches and a green coat. A black hat, a green cloth belt, white leggings and black shoes completed the uniform.

and was originally made for display aboard USS Boston (CAG-1). (Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command)

Although they no doubt were the best dressed Marines of the Revolution, Jennison’s men had their share of problems. Shore leave, for example, was hard to come by. No Navy officer, not even the skipper, could grant leave to a member of the guard if the Captain of Marines objected to the man’s going ashore. Seldom did anyone, either Sailor or Marine, try to slip past the sentinels to spend the evening at some friendly tavern. Skippers tried always to anchor far enough from shore to discourage even the best swimmer, and the ship’s boats were carefully guarded.

The voyage got off to a bad start. The frigate had traveled no more than 5 miles, when “the ship’s first lieutenant fell overboard and by catching hold of the flukes of the anchor, which he was trying to fish, was haply caught and got on board.” Worse misfortunes were soon to follow.

On the morning of Feb. 19, three vessels appeared on the horizon. One of the ships veered off in pursuit of the Boston and kept up the chase in spite of dense clouds, darkness and rain. As if the presence astern of this British frigate were not bad enough, shortly after midnight on the 21st, the rain grew heavier, accompanied by winds of near hurricane force. At the height of the storm, lightning struck the American frigate’s mainmast, coursed downward into the hold, and finally passed through the ship’s keel. “A Terrible night,” wrote Jennison in his journal. The captain of the mainmast was struck with the lightning, which burned a place in the top of his head about the bigness of a quarter dollar. He lived three days and died raving mad.”

The hurricane continued to rage throughout the hours of darkness. Although Jennison later confessed that he spent most of the night “absorbed in the Abyss of Reflection,” Capt Tucker had no time for philosophizing. The skipper called for reports of the damage inflicted by the storm and learned that between four and five feet of water had poured into the hold. The Sailors were ordered to man the pumps, as the ship butted stubbornly against the raging sea. Within a quarter of an hour, the weary seamen had lowered the water level to three feet; the vessel was saved from the storm. “Providence ruled,” commented Jennison in his journal.

There still remained the menace of the British warship not far astern. Tucker waited until the storm had slackened, then ordered the quartermaster to change course. The flashes of lightning were fewer now, so that the night remained dark for several minutes at a time. A lightning bolt split the skies; and as soon as the searing light had died away, the American frigate swung sharply to starboard. When the lightning next flashed, the British lookout scanned the seas in vain for some trace of the Boston. Tucker had successfully eluded his pursuer.

Again on March 10, a hostile sail inched over the horizon. The 16-gun British brig Martha boldly closed the range. At high noon, Jennison later noted in his diary, “she fired three guns at us, one of which carried away our mizenyard.” This “Ball,” according to John Adams, “went directly over my Head.” The Boston replied with a devastating 12-gun broadside, and the battered Martha quickly struck her colors. When Tucker strode along the deck to survey the damage done to his ship during the brief action, he came face to face with John Adams, musket in hand and wearing the green coat of a Continental Marine. “What are you doing here?” asked the skipper. “I ought to do my share of fighting,” the future president of the United States replied.

This was the last action fought by the Boston on her voyage to France, but further bad luck was to befall the vessel. On March 13, Tucker sighted an unarmed British merchantman and called for the gunner to fire a shot as a signal for the approaching vessel to halt. “Mr. Barron, Capt Palmes and myself,” wrote Jennison, “were sitting on the main gratings, when the Captain called for the Gunner to fire a nine pounder.” All three men rose to their feet and, with Barron in the lead, started toward the gun that was being loaded. No sooner had the young naval officer reached the squat, ugly cannon than it exploded, wounding three members of the gun crew and shattering Barren’s leg. “He was carried,” continued Jennison, “to Dr. Noel (who had been the principle surgeon in the Army under Gen Washington) who amputated his leg and dressed his wounds.” “I was present,” wrote John Adams, “at this affecting Scaene and held Mr. Barron in my Arms while the Doctor put on the Turnequett and cutt off the Limb.” Despite the ship’s surgeon’s efforts, however, he was unable to save the lieutenant’s life. Ironically, the vessel at which the shot was to be fired turned out to be a British merchantman that had been captured a few days earlier by the French and was being sailed into port by a prize crew.

LT Barron was buried at sea on March 26. His body was placed in a wooden chest along with several 12-pound shot. A piece of the shattered cannon was then lashed to the top of the makeshift coffin. After one of the ship’s officers had read the burial service, the weighted box was pushed through an opened gun port and allowed to plummet “into his watery grave.”

On April 2, after riding out another fierce storm, Boston anchored at the French port of Bordeaux where John Adams, went ashore.

Boston had been so battered during the crossing that she was not fit for another cruise until June. After mending the leaking hull, repairing or replacing sails, and recruiting a number of French sailors, Tucker put to sea and spent the summer of 1778 operating against British shipping in the Bay of Biscay. During these months, Boston’s Marine guard was again put to the test, for trouble was brewing on board the frigate.

Late in May, even before the ship had sailed from Bordeaux, two seamen informed the master-at-arms that they had been asked by another sailor to join in a plot to seize the ship. Jennison and the Marines quickly arrested the ringleaders, but this did not prevent further trouble. On July 17, one of the American sailors tried to stab a French recruit who had recently joined the ship. The assailant was arrested by the Marines, tried, found guilty, and given 42 lashes. Thanks to the Marines, order eventually was restored, and the vessel returned that autumn to Boston, pausing en route to conduct a successful raid on the British fishing fleet off Newfoundland.

In April 1779, while Boston rode at anchor in the Mystic River, Jennison obtained Tucker’s permission to serve in the privateer Resolution, a light but swift vessel manned by a crew of 35 men and mounting only six guns. The Resolution, Jennison and the others hoped, would be able to capture several British fishing vessels, bring them back to Boston, auction off the cargoes, and divide the profits. Privateering, in short, was a kind of legalized piracy that could be practiced against the enemy in time of war.

On this particular cruise, however, there were no profits. On May 10, off the Newfoundland coast, the Resolution sighted a sail and altered course to investigate. The stranger proved to be no fisherman, but rather the Blonde, a 32-gun frigate in the service of His Majesty the King. Before the sun had set, Jennison and his fellow privateers were prisoners of war.

The men of Resolution were sent to a hastily constructed prison compound at Halifax, Nova Scotia. The moment they arrived, they began laying plans for their escape. Using spoons and pieces of broken pottery, Jennison and the others managed to weaken three of the wooden pickets that formed the outer wall of the stockade. On the afternoon of July 29, a dense fog rolled over Halifax. The prisoners, 10 men in all, quietly broke off the weakened pickets and began crawling through the opening, but the alarm was given even before the last man had made his way out of the enclosure. Only one of the 10 got away. He promptly got lost in the fog, wandered in a vast circle, and was recaptured a few hours later when he blundered through the prison’s main gate.

In spite of this failure, Jennison was not destined to remain for long a prisoner of war. He was exchanged on Sept. 22, 1779, for a British officer of equal rank who had been captured by the Continentals. Upon regaining his freedom, he reported immediately to Tucker. Since another Marine officer had been assigned to the frigate as Jennison’s replacement, the ex-prisoner was appointed purser, a job that required him to wear a Navy uniform. Instead of serving as second in command of the Marine guard, he now was responsible for laying in, storing, and distributing the food and clothing required by tie frigate’s 200-man crew.

Since the British fleet had, by now, gained control of the North Atlantic, the Boston and other surviving American frigates took refuge during the winter of 1779 at Charleston, S. C. This change of port, however, merely postponed the destruction of the Boston and the other gallant ships. On Feb. 11, 1780, while a British fleet blockaded all routes of exit from the harbor, 10,000 British soldiers and Marines landed to lay siege to Charleston. The outcome was inevitable, for only a handful of ships and no more than 4,000 troops were available to defend the city. Yet, in spite of the overwhelming British numbers, the Americans held out until May 11, a day about which the Marine officer made only a single comment, “A flag to the enemy accepting the terms offered.” After the surrender, Jennison and the other Continental officers were released, provided that they took an oath that they would take no further part in the war. This practice of granting paroles to prisoners of war was quite common during the Revolution.

Thus ended the military career of William Jennison, who served his country in all three branches of the Continental service. When Congress authorized the recruiting of Marines—men able to fight on land as well as at sea—Jennison was precisely the kind of person that the Revolutionary lawmakers had in mind. After the war, he married Nancy Vibert of Boston, abandoned the study of the law, and became a schoolmaster first at Vicksburg, Miss., and later at Baton Rouge, La. He died in Boston in 1843 at the age of 86.