The Ring: A Tale of Tragedy, Love And Serendipity

By: Kipp HanleyPosted on August 15, 2025

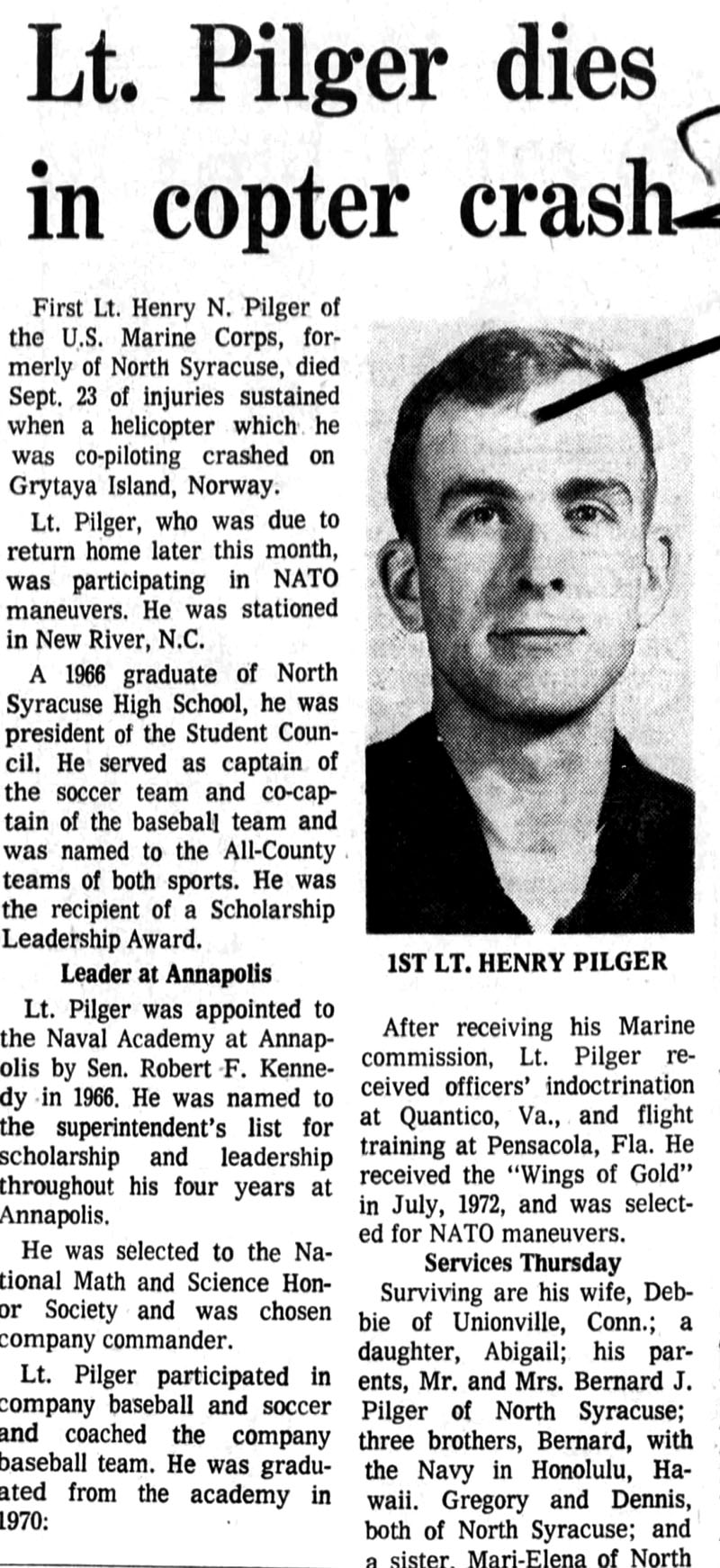

In the fall of 1972, First Lieutenant Henry N. Pilger was 24 years old, a newly minted Marine Corps aviator, husband and first-time father.

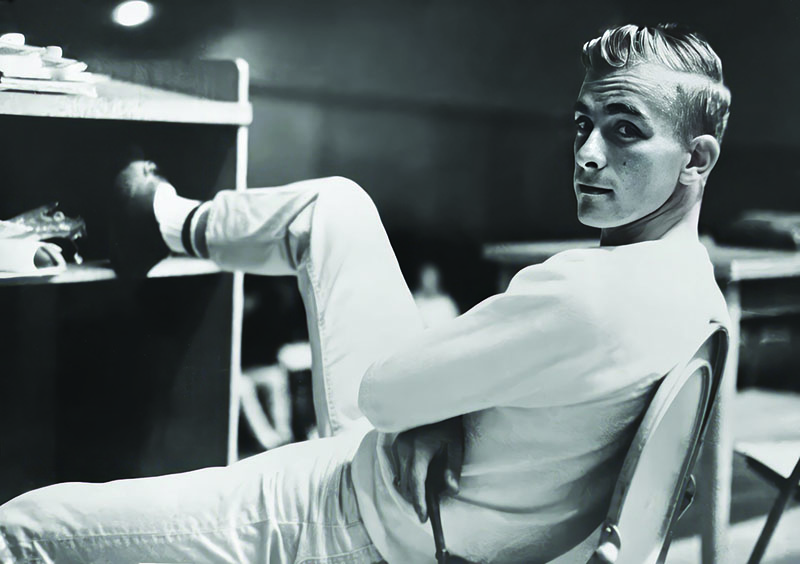

Known as ‘Captain Easy’ on the campus of the U.S. Naval Academy just a few years earlier, the handsome and athletic lieutenant from Syracuse, N.Y., was stationed at Marine Corps Air Station New River, N.C., with Marine Light Helicopter Squadron 167 when he got the call to participate in NATO Exercise Strong Express in Norway.

Strong Express was a huge NATO exercise designed to show the alliance’s strength during the height of the Cold War with the former Soviet Union. But as the otherwise successful exercise was nearing completion, tragedy struck on the mountainous Norwegian island of Grytoya, north of the Arctic Circle.

On Sept. 23, Pilger, the copilot, and four other Marines died when the UH-1N helicopter they were flying in crashed. They were en route to pick up Marines from the mountainside. On the flight with Pilger were HML-167 squadron mates First Lieutenant Gerald Merklinger, pilot, and crew chief Lance Corporal Pete Rodriguez. Also on board the aircraft were Captain Raymond Wilhelm “Bill” Reisner, a communications officer, and Major James Skinner, a pilot who was assigned to the headquarters element of the provisional Marine Aircraft Group for the exercise. (Executive Editor’s note: Skinner was posthumously promoted to lieutenant colonel.)

Due to the secretive nature of the exercise, the accident appeared to be the end of the story for the relatives of those who perished. Unsure of what exactly happened, Pilger’s wife and other victims’ relatives went on with their lives as best they could.

“As I heard it, my mother was so pleased he was chosen for that mission as opposed to Vietnam because no one died in NATO,” said Pilger’s daughter Abby Boretto, who was just 15 months old when her father died.

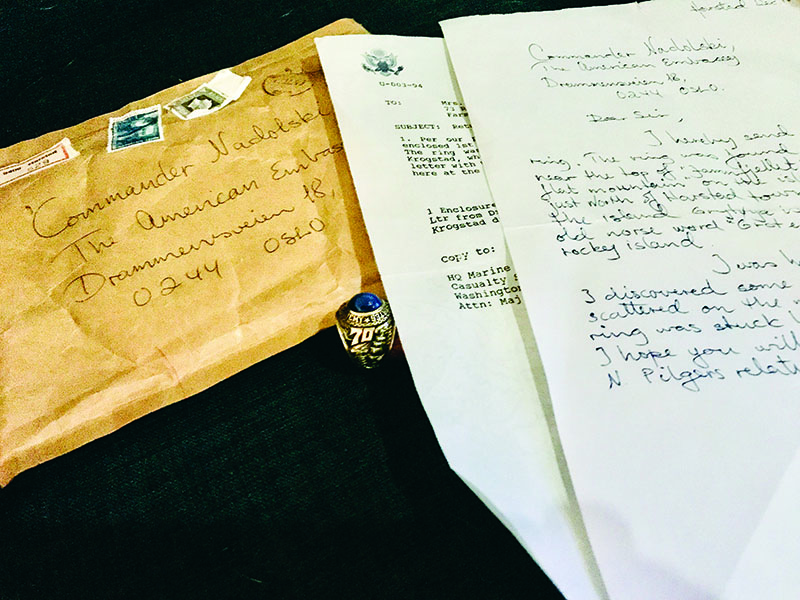

But 22 years after the accident, Pilger’s Naval Academy class ring with a beautiful blue stone and his name inscribed on the inside of the ring appeared one day in Boretto’s mailbox in Connecticut. The ring was virtually unscathed, yet it was riddled with emotion, so much so that her mother, Deborah, wanted nothing to do with it.

But Boretto kept it, packing it up each time she moved to a new house. In a way, Boretto felt like it was a sign. Two years before the surprise package, she was swimming in Hawaii and lost a replica of her dad’s ring given to her by her mother. She never gave up hope of finding it, even though it was likely somewhere at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

“I was swimming in the ocean, and it flew right off my finger and right into the ocean,” Boretto said. “It was a gut punch. … I was sick about it. [But] I made this strange proclamation that the ring would come back to me. … Sure enough, here comes this ring in this package.”

Boretto eventually got married and raised her children in San Diego. When Boretto turned 50 in 2021, with her children grown, she had the time to investigate the mystery of her father’s class ring. So one day, she brought out the ring and the note from the ring finder Hans Krogstad and began her search to get to know her father and how he died.

“I always knew this was a spectacular story … but all that I had was this miraculous gift, the ring, returning home to me after this large amount of time,” Boretto said. “It had been 21 years up on that mountain. This ring lasted through all of those elements, all of those years. So that is all that I had, this ghostly connection. … So, what is the rest of the story?”

In 1993, Hans Krogstad was an obstetrician living in a tiny Norwegian town called Harstad, just a stone’s throw from Grytoya. He often would hunt birds on the island. One clear September day, shotgun in hand, he stumbled upon what he thought was debris from a nearby airfield.

When he looked closer, he found the remains of a glove and a gold ring, set with a beautiful blue stone, lying on the rocky landscape. He scooped it up for further examination and saw Pilger’s name scripted on the inside of the ring and that it was from the U.S. Naval Academy.

As the brother of a military officer and an aspiring military pilot—his vision prevented him from flying helicopters—Krogstad was hopeful that the ring could be reunited with the rightful owner. With the Internet in its infancy, he called his friend at the U.S. Embassy in Oslo to see if he could assist him. Eventually, a Navy attaché who graduated from the Naval Academy was able to send the ring across the Atlantic Ocean.

Not knowing whether it reached Pilger’s family, Krogstad went on with his life but never forgot about the trinket he had found. Before giving it to the attaché, he had a coworker take a picture of the ring. A few years after mailing off the ring, the widespread use of GPS allowed him to accurately determine the coordinates of his discovery.

Fast forward more than 20 years later and Krogstad happened to run into his former colleague in a local shop. He asked whether he still had the images he took in 1994 so he could digitize them. Within a week, he had the photos, further fueling his interest in finding the family.

A series of phone calls with various government employees ultimately resulted in Krogstad finding out that not only had the family received the ring, but Pilger had a daughter who was looking to reunite with the person who found it.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Boretto had already found out what happened to her dad thanks to Freedom of Information Act requests (the documents were now declassified) and assistance from a Marine who was there that day. Sergeant Rocky Shaw was serving in the NATO exercise in the same unit that Skinner was assigned to [H&MS-31] when he first heard about the crash. Serving on board USS Inchon (LPH-12), which was anchored 40 miles from the island, Shaw knew a helicopter had gone missing that day and remained curious about what exactly happened. Eventually he found Boretto on Facebook in 2021—coincidentally, while she was visiting her dad’s old stomping grounds in Syracuse to find out more about what he was like as a child. Soon Boretto and Shaw began sharing crash reports, with Shaw helping to fill in the gaps about the mission.

Boretto and Shaw began to track down descendants of the others who died in the crash. As they connected with the Marines’ relatives, the idea for a documentary was now buzzing inside Boretto’s head, but she had no idea how to make one. One day, her aunt told her about a similar ring recovery documentary about World War II. She immediately contacted the grandson of the featured WW II veteran and, within 24 hours, was on the phone with him about creating her own project.

At the same time, Aleksander Viksund, a friend of Krogstad’s and former second lieutenant in the Norwegian Army, had recently read about the crash in a story by a local journalist and thought it was a good idea to memorialize the Marines who died that day.

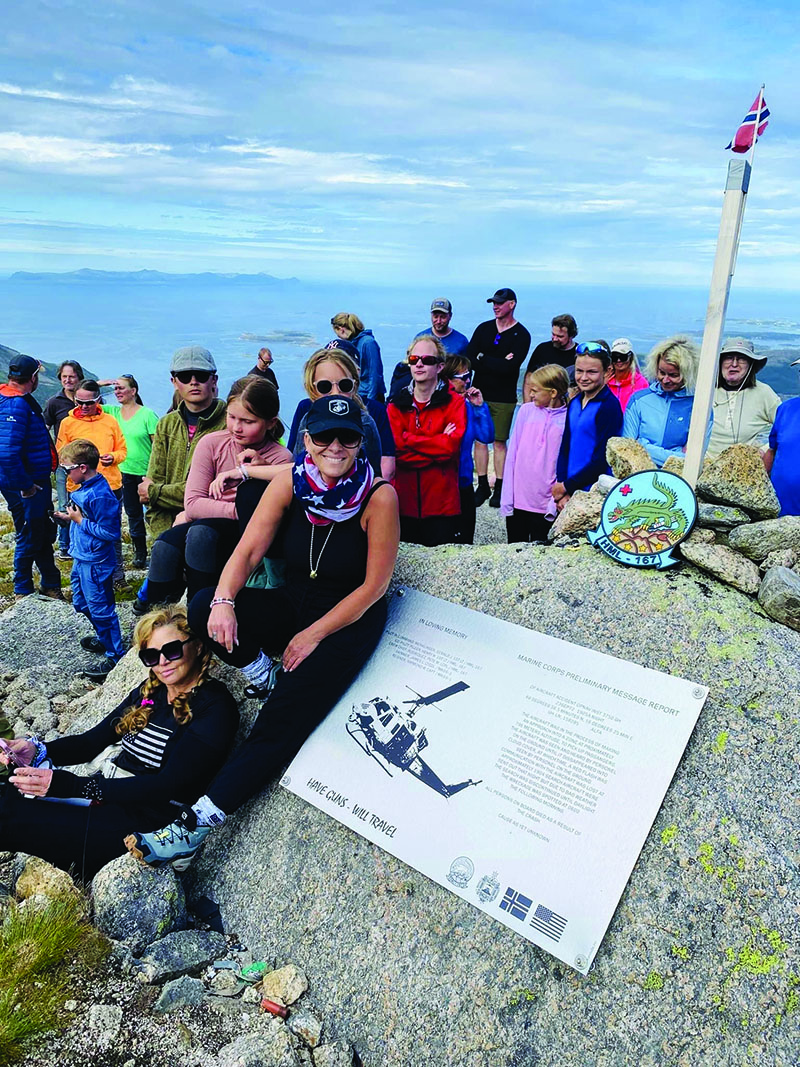

So Viksund assembled a team of local residents to make a plaque and mount it on the rock-strewn crash site, which lies more than 2,600 feet above sea level. The plaque contains the victims’ names, the preliminary message report of the accident and a helicopter engraved over the words “Have Guns – Will Travel”—the HML-167 slogan.

“For Dr. Krogstad and me, it was important to do the five Marines this honor,” Viksund wrote to Leatherneck in an email. “We both grew up in the Cold War days and think that the effort of our allies is not to be taken lightly. It is a big deal for most of us living here up in the high north that young men and women from our allies are willing to serve in our country to help us keep the bullies in the East at bay.”

“He said, ‘This is part of the history of the island,’” Krogstad said. “ ‘They lost their lives preserving the peace of Norway.’ And I said, ‘That is a good idea.’ ”

In 2022, Boretto, a handful of crash victim relatives and several Marines past and present came to Norway for the unveiling of the memorial. Boretto saw Krogstad in-person for the first time that day on the mountainside, experiencing a rush of excitement from meeting the man who preserved her father’s memory for her.

“I thought going into it, I would be really emotional, but that wasn’t the feeling at all,” Boretto said. “I was super invigorated. … I felt like it was a release; I finally had met my father for the first time.”

For Krogstad, meeting Boretto was the culmination of curiosity and a bit of old-fashioned luck, or what some would describe as fate.

“It’s a strange story,” Krogstad said. “If I hadn’t had met my medic, who took a photograph of the ring, it [the story] probably would have ended there.”

Boretto’s documentary “The Ring and the Mountain” was eventually unveiled in January of 2024 on board the USS Midway Museum, located on the San Diego shoreline. The event was held on what would have been Pilger’s 76th birthday. According to pilot Wilhelm Reisner’s sister Nancy Paxton, she could not look at a photo of her brother without getting emotional until her trip to San Diego for the documentary debut. While it was not cathartic in every sense, the trip did help her deal with her brother’s death a little better.

Manuel Rodriguez, younger brother of crew chief LCpl Pete Rodriguez, also attended the event. Upon learning of the details of his brother’s death while defending freedom overseas, Manuel started to look at him as a hero. In fact, he fought—albeit unsuccessfully—to get a nearby elementary school named after his sibling.

Health issues prevented Skinner’s daughter Linda Wood from attending the memorial ceremony in California. However, the work done to unite the families of the deceased and to highlight the Marines has left “her heart full.”

“There are no words to say how proud I am and grateful for everybody that stepped up to do these stories and remember these five Marines,” Wood said. “And not just my dad, but on behalf of so many. There are hundreds of thousands of families that have gone through the same loss. These men and women, they put their lives on the line. They are so dedicated.”

Viksund said his Norwegian community has made “friends for life” thanks to the efforts from folks like Boretto, Shaw and Colonel Slick Katz, USMC (Ret), who serves on the USMC/Combat Helicopter and Tiltrotor Association board of directors and assisted in the search for the victims’ relatives. Katz served with HML-167 during the Vietnam War and presented a plaque and letters of appreciation from the squadron at the memorial’s dedication.

“We were amazed at how thankful the family members were of our efforts, and how much the efforts were appreciated by the U.S. Marines,” Viksund wrote. “We are very happy that this meant so much for the families, the USMC and the squadron HML-167.”

For those interested in the documentary, visit https://youtu.be/-hAXqTpZuIo.

To learn more about the Marines who died on Sept. 23, 1972, please see the story “Grytoya Marines” in the September 2025 issue of Leatherneck Magazine.

Author’s bio: Kipp Hanley is the deputy editor for Leatherneck and a resident of Woodbridge, Va. The award-winning journalist has covered a variety of topics in his writing career including the military, government, education, business and sports.