Shattered Nerves, Quick Death: A Scout Sniper Platoon on Iwo Jima

By: Geoffrey W. RoeckerPosted on January 15, 2025

Executive Editor’s note: We bring you this article to mark the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima, considered one of the Marine Corps’ touchstone battles. See page 44 to read about Harlon Block, one of the Marines who helped raise the second flag on Iwo Jima.

Robert Floyd Pounders was not the type to shrink from a challenge. The self-described “scrawny country boy” refused to stay on the family farm in Pinson, Ala., while his friends went into military service. In February 1943, he presented himself at a Birmingham recruiting office, desperate to join any service that would take him—but only the Marine Corps would accept this colorblind, underweight and underage recruit. Floyd was only 16 years old when he enlisted, but boot camp at San Diego, machine gun school at Camp Elliott and infantry training at Camp Pendleton had a transformative effect. “Aided by good food and a strict schedule, I gained 42 pounds, and I don’t think you could have called me fat,” he recalled. “I felt I could whip my weight in wildcats.”

As a member of the 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, Private Pounders crewed a heavy machine gun at the battle of Roi-Namur and carried a Browning Automatic Rifle on Saipan and Tinian. He completed three campaigns in just seven months, coming through virtually unscathed with a combat meritorious promotion to corporal and a letter of commendation for brave and efficient service. In the fall of 1944, at the ripe old age of 18, Floyd Pounders was leading a four-man fire team in a rifle platoon, training at Camp Maui and speculating about what lay ahead. Some of his buddies thought their next stop would be Japan itself—a most unwelcome prospect after facing die-hard Japanese fighters and desperate civilians in the Mariana Islands.

One morning in November, Floyd learned that his regiment was seeking volunteers for a new “Scouts and Snipers” platoon. “I don’t remember how anxious I was to volunteer, but I did anyway,” he said. “I knew that the training had to be different from the training we were doing in the rifle company.” There was another attraction for a veteran line infantryman: “I knew from experience that considering the type of fighting the Marines did, the scouting part would be minimal.” Perhaps he could pick up some new, interesting skills—and increase his chances of surviving the war. Corporal Pounders put in his name and became one of the first volunteers accepted for the platoon.

Marine Corps training for specialist “scouts and snipers” had a rough start in the World War II era. Despite the demonstrated value of highly trained sharpshooters in the Great War, opportunities to improve on these advantages were subject to “the ebb and flow of the general pre-war indecision with regard to adopting new equipment and training personnel,” and proper evaluations of equipment and training did not begin until late 1940. The result, notes historian Peter Senich, was that on Dec. 7, 1941, “the Marine Corps was not prepared to field or equip snipers.” Nearly a year passed before dedicated training facilities could accept significant numbers of students.

Combat experiences shaped the training regimen. Dismayed at the poor quality of Marine patrolling on Guadalcanal, Lieutenant Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Whaling established an on-island training program. Hand-picked volunteers spent a few weeks with the “Whaling Unit” learning marksmanship and fieldcraft, stalking, laying ambushes and gathering intelligence. They were most effective when operating semi-autonomously in teams of two or three, deploying as needed to solve tricky tactical problems. Tarawa provided another stark lesson: a scout-sniper platoon could be used as shock troops, but not without prohibitively high casualties among highly trained, hard-to-replace specialists.

On Saipan, the 4th Marine Division’s recon company had to parcel out its scout-snipers as replacements for other units, negating their combat effectiveness. The division’s report on the operation recommended adding a scout-sniper platoon to every infantry regiment.

First Lieutenant William T. Holder of Carbondale, Ill., took charge of the 24th Marines’ scout snipers. Described as “a little man who looked almost too young to be an officer,” the 22-year-old Bill Holder knew how to fight with every inch of his 5’6” frame.

As a junior platoon leader at Roi-Namur, he helped rally his company (F/2/24) when an exploding ammunition dump caused heavy casualties and stalled the advance. He was slammed to the ground by an artillery shell shortly after landing on Saipan, but “although painfully wounded … brilliantly led his platoon during the entire operation.” Holder’s performance earned him the Silver Star and the Purple Heart, and Fox Co was sorry to lose such “a darn good, fair, and courageous leader.”

Enthusiasm for the project was low. “They didn’t get all that many volunteers,” admitted Pounders. At the first roll call on Nov. 19, 1944, the scout-sniper platoon mustered Holder and eight enlisted men. Floyd Pounders was there with a buddy from “Baker” Company: Private First Class Charles C. DeCelles, a Gros Ventre youth from Montana commended for service on Saipan. Cpl Ben Bernal served through three battles with K/3/24; Cpl Loren T. Doerner had the same pedigree with the 4th Tank Battalion. Both wore the Purple Heart. Sergeant Ralph L. Jones was the recipient of a Silver Star for manning a mounted machine gun at Roi-Namur, and the corpsman, Hospital Apprentice 1st Class Charles “Pills” Littlefield, earned the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for treating wounded men under fire.

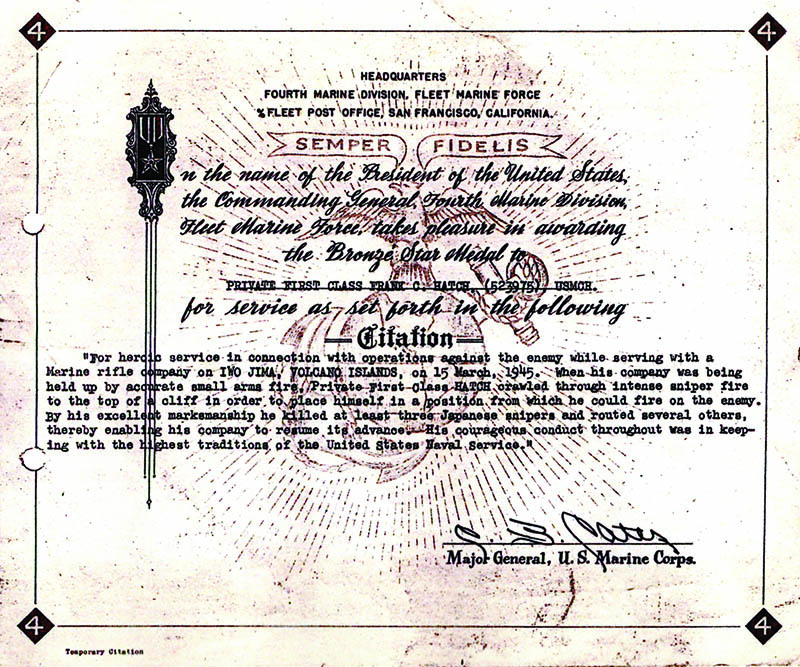

While lacking combat experience, the other two volunteers at least had some advanced infantry training. Private Frederick J. McCarthy of South Portland, Maine, was a skilled BARman despite having only a few months in uniform. The other, PFC Frank Hatch, was coming up on two years in the Marines. As the third-best shot in his recruit platoon, Hatch qualified for the “Expert” medal—“less than a dozen of us made it”—and a promotion to PFC immediately after graduation. He became a coach at the Parris Island rifle range, but the job wasn’t to his liking. “Didn’t study, didn’t advance, didn’t stay,” he said. “It was off to the Pacific to be a replacement in the 4th Marine Division.” Hatch landed in the machine-gun platoon of C/1/24 but “never did like the idea of a machine gun. I would rather connect with one bullet than spray an area with many.”

Volunteering for a sniper outfit was a no-brainer. With no more volunteers coming from the regiment, Holder turned to the 17th Replacement Draft. PFC Jack Stearn recalled sitting in an outdoor auditorium when “a lieutenant jumped on stage and said he was looking for volunteer scouts.” He received a mixture of volunteers and “voluntolds” from the group of mostly spring 1944 inductees. Stearn, one of the Marines “recommended” by a company commander, was the only one with combat experience. A pre-war Army enlistee, he earned a commission and served as a shore party officer on the beaches of Sicily. After multiple run-ins with a certain major, First Lieutenant Stearn resigned his commission and returned to civilian life, only to enlist in the Marine Corps one week later. He was impressed by the “higher standard, tough agenda, higher expectations [and] stern discipline,” and “felt 10 feet tall the day I graduated from boot camp.”

With the platoon up to strength, Holder assigned roles to his 30 Marines. Sergeants James D. Huff and Harry F. McFall Jr., former drill instructors, were appointed platoon sergeant and platoon guide, respectively. PFC Stearn was good with maps, so Holder tapped him as a runner and radioman. Sergeant Jones took charge of 1 Squad, while the senior corporal, 18-year-old Floyd Pounders, led 2 Squad. Each squad had two groups of five men: a leader, a sniper, a rifleman/spotter, and a BAR gunner and assistant. Snipers like PFC Hatch were promised M1903 rifles with telescopic sights—as soon as any were available. They would have to make do with the M1 Garand for now.

The platoon trained separately from the rest of their regiment, practicing everything from the basics of scouting, patrolling and reconnaissance to the more complicated tasks of counter-sniping and mopping up bypassed fortifications. Holder scheduled a week-long field exercise, which doubled as an enjoyable goat-hunting trip through the Maui backcountry. Unfortunately, the hunt resulted in the platoon’s first casualty when a Marine was accidentally shot in the face. “I remember us carrying him on a stretcher, a bandage wound around his cheeks and head, and his eyes looking up at us,” said Hatch. A few weeks later, most of the platoon would have given anything to trade places with their injured friend.

Two last-minute additions joined the scout snipers at the very end of December—PFC Anthony J. Ranfos and Sergeant Elmer G. Smith, both combat veterans—and in mid-January, the entire 4th Marine Division embarked for Operation Detachment. The long trip was mostly unremarkable, except for the red-letter day when the snipers finally received their scoped rifles. “This was a hell of a time to get them,” Hatch said.“They needed sighting in. [I would] toss something overboard, let it float off, and shoot at it, someone beside me telling me where the bullet hit, and adjust the sights accordingly.” He couldn’t dial the weapon in precisely but figured “when we landed, I would get more practice.”

Pounders was far less flippant: when he saw topographic maps of Iwo Jima and realized it was only 600 miles from Japan, “the fear really set in and I realized that this would probably be one of the toughest battles that we had experienced. Until now the trip had been training, schooling, lounging, and eating well, but now all of a sudden things had to get serious and for real.”

As reserves, the platoon spent the better part of Feb. 19, 1945, watching the battle from the decks of USS Bayfield (APA-33). Hatch, new to combat, thought the whole spectacle “a pretty good show” until Bayfield began receiving badly wounded Marines. The less-experienced men kept up their confidence on the boat ride to the beach. PFC Stearn played “The Marines’ Hymn” on an ocarina, and Private Robert F. Ragland declared, “We’ll go through ’em like sugar through a tin horn.” Cpl Pounders thought differently. “Sgt Jones, myself, and Sgt McFall were the first ones off the landing craft,” he remembered. “I had been this route before, so I knew we must get away from the boat as soon as possible. I had no trouble getting my squad to follow me … but some of the guys who were last to get off said one of the [LCVP] gunners was hit.”

The first look at Iwo was grim. “My first sight as I climbed the beach was a vehicle like an open tank [an LVT], someone hanging half in, half out—dead,” said Hatch. Pounders noticed “more than the usual number of bodies and parts of bodies laying around … We ran past an amphibious tank with one of its tracks blown off. The vehicle was on its side. With so many bodies around, we couldn’t tell if any of them were killed when the amphib was hit.” The scout-snipers quickly dug in on a beach “white hot with artillery and mortar fire. The air was a spray of sand and jagged, murderous chunks of shattered shell fragments.” To PFC Stearn, “it seemed as if I was in a madhouse.”

At first, the scout sniper platoon functioned as intended: “running errands, locating lost units, and filling in gaps in the lines,” according to Pounders. They posted security around the CP at night, carried stretchers and collected identification tags from fallen Marines. Sergeant McFall led the platoon’s first successful reconnaissance patrol to caves overlooking the airfield. On their way to draw rations, Corporal Bernal and Private Carl F. Rothrock spotted two enemy soldiers in a cave and dispatched both in less than a minute. They also suffered their first combat casualties: corpsman “Pills” Littlefield on D+1, and Sgt Elmer Smith on D+2.

On one memorable night, a lone Japanese airplane dropped two bombs on the platoon. The first bomb, a dud, landed 4 feet from Hatch—a nasty shock when he awoke in the morning—but the other exploded near PFC Stearn’s group, caving in their foxhole. Stearn and Ranfos dug their way out, then checked on the third occupant, PFC LaRue L. Stevenson. “We saw his feet sticking out of the sand,” Stearn recalled. When we finally got him out, we laughed like crazy. Stevens was just sputtering and raising hell.” Hanging around the CP felt like sitting on a bull’s-eye. The platoon’s “restlessness and nervousness” increased, and a teenaged BARman was evacuated due to “war neurosis.”

Orders to move up toward the line felt almost like a blessing. The route led through “a broken area of death traps, blasted holes, undermined with winding labyrinths of caves,” in the words of SP3c Bryce Walton, a correspondent covering the platoon for Leatherneck magazine. At night, the island itself worked on their nerves. “They came to know the meaning of fear,” Walton continued, “fear of the unknown. The nightmare terrain, the bent dwarf trees and jumbles of rock seemed to take on life.” The Japanese were always watching. “We were hunting for snipers, and the mortars were following us,” Cpl Bernal said. “One of the mortars got me.” His long combat career was over. The same blast nicked Pvt Ragland’s leg. “Just a scratch,” he declared and continued his patrol.

Toward evening on Feb. 24, the platoon received orders to plug a dangerously wide gap between K/3/24 and E/2/25. As they moved up in a skirmish line, Japanese fire erupted all around.

“It seemed as if they were shooting from everywhere,” PFC Stearn recalled. “I zigged but didn’t zag, and seconds later felt as if I had been hit with a sledgehammer. I grabbed my shoulder trying to stop the blood that was pouring out.” Sergeant Huff bandaged Stearn and ordered him back to the aid station—which meant running the gauntlet the other way. A sword-wielding Japanese officer tried to slash at Stearn, but a quick-shooting PFC William S. North knocked Stearn to the ground, finished off the officer, then picked up his wounded buddy and ran like hell as mortars began dropping around them. Stearn survived, but his misfortune was a preview of what lay ahead.

Filling holes in the line was expected of the scout-snipers—but intended as a temporary assignment, terminating when another infantry unit took over. On the morning of Feb. 25, however, no reinforcements arrived. Instead, Holder learned that his platoon was expected to attack alongside the rifle companies. The men were tired from hours of night fighting, and although heavily armed, frontal attacks against fortifications were not part of their training. Orders were orders, and at 9:30 a.m., Holder led his platoon toward a sharp cliff a few hundred yards away.

They walked into a perfect killing field. “There was no more vegetation for cover because planes and artillery had already destroyed it,” remembered Pounders. “As we broke out into the open, all hell broke loose.” Lieutenant Holder was first to fall, blood streaming from a severe head wound. Sergeant Huff suddenly found himself in command. Ragland and Rothrock were dangerously exposed, gamely firing back at invisible enemies. Huff motioned them to a nearby crater as Sgt Ralph Jones withstood the withering crossfire to cover his buddies.

“After the three were down out of imminent danger, Jones sent a last round at the side of the cliff,” reported Walton. “Then he spun around as a return hail of machine gun fire found him.” The 1 Squad leader was dead before he hit the ground.

Huff knew at least three scout-snipers were down, but had nothing on the others. Ragland leaped into the next shell hole, landing beside Bill North and Private Edward Rindfleish Jr. North was already dead, and Rindfleish’s right arm hung useless, the bones shattered. Sgt McFall tumbled in, dragging a stunned Private John E. Sessinger. After getting the wounded men out of harm’s way, McFall and Ragland sprinted back to Huff with the casualty report. McFall brought some good news: 2 squad was taking cover in a large shell hole, mostly intact. The attack was clearly failing, and the rifle companies on the flanks were falling back to reorganize. Huff decided to follow suit—but first he had to extricate his pinned platoon.

PFC Hatch was sniping at firing ports when he got the word to withdraw. He tumbled into a hole with three other Marines, almost impaling himself on their fixed bayonets. One man, nerves strained to the breaking point, urged everyone to jump and run at once. “Guess he hoped the others, not him, would be the ones to be shot at,” Hatch commented sourly. When nobody moved, the frightened Marine began repeating Hail Marys. “I countered with ‘yea, though I walk through the valley in the shadow of death.’ ” Somehow, the group made it back to relative safety.

Over in 2 Squad’s hole, Pounders was using a combat veteran’s common sense: “As far as I was concerned, we had to wait for a break or some help.” He was unmoved by McFall’s mutterings of “someone ought to DO something,” or the sergeant’s decision to leave the hole, firing a Tommy gun at invisible enemies hundreds of yards away. When McFall’s SMG stopped, Pounders assumed he was dead. The corporal scouted a route back to their starting point, waited for the fire to die down, and led his men back with only one additional casualty. As he tried spotting positions for Sgt Huff, Pounders evidently missed seeing McFall—still alive and busy with the radio, delivering unwelcome news. The attack would resume at 1:30 p.m.

Huff did his best to even the odds, helping reestablish a machine-gun position and coordinating with the nearest company CP. An enemy bullet grazed his side as “the Japanese seemed to know another advance was gathering and were intensifying their fire.” Then a Japanese machine gun stitched across the position, and Huff cried “I’m hit!” McFall went to his aid, but the enemy was waiting. “Ragland tried to yell as he saw little puffs of dust and splintered rock run along the ground toward McFall,” wrote Walton. “Then the path of bullets traveled across the small of McFall’s back. The sergeant raised up, mumbling something towards the Japanese lines, and fell backward, firing his Tommy gun blindly.” Huff’s poncho and field glasses blunted the bullet; he was not hurt but felt sick to his stomach that McFall “died trying to save him because of a wound he didn’t even have.”

The second attack angled to the right, avoiding the open ground. Huff’s men crept cautiously through the scarred, blasted area, finding the bodies of friends along the way. One man in Pounders’ platoon stumbled into a shell hole with a dead Marine. “His mind snapped,” said Pounders, “he was crying and hanging on to me with a death grip. I can still hear him saying, ‘Floyd, you’ll be killed if you go back.’ He also kept saying he had killed the dead Marine, but he couldn’t have—he was dead long before we came up to the shell hole.” Pounders guided the broken man back to the aid station.

Finally, the scout snipers found a few deep holes in which to spend the night. “The first night up here, they had occupied 10 foxholes,” wrote Walton. “Now they did well to fill up three.” Only nine of the 32 men who landed on Iwo were left to hold the line. The dead included Sergeants Jones and McFall, PFC North, and Private Arling F. Derhammer; PFC Ranfos died of wounds three days later. Seven were evacuated with bloody wounds; five more suffered the effects of blast concussion or “war neurosis.” Frank Hatch maintained his composure all day but lost it when he realized how many friends were gone. “Boy, did I cry and cry,” he recalled. “They thought I was going to crack up.”

After Feb. 25, the ruined platoon “was used in perimeter defense of the CP until near the end of the operation.” All of the survivors were suffering shock to some degree; their recollections of the following weeks are somewhat jumbled and contradictory, a blur of mop-up missions, filling holes in the line, helping wounded Marines and searching Japanese bodies. On March 15, a front-line outfit actually requested a counter-sniper mission. Pounders collected Hatch, who was thrilled to have live targets in his sights at last, and Private Marion W. “Buddy” Saucerman with a BAR for protection. The trio crept up a small hill overlooking Japanese territory and watched their foes moving supplies into a cave. One unfortunate soldier carried his heavy buckets into Hatch’s crosshairs. “Hatch fired,” Pounders said.

“The [enemy] threw up both arms, his buckets went tumbling, and he grabbed the cheeks of his buttocks and ran into the cave.” Hatch chambered another round and Pounders cheered, “You hit him in the ass!”

As the scouts climbed down to check their handiwork, a Japanese machine gun opened fire on Saucerman. “I heard the snapping of bullets, and he went down in a heap, a bullet across the back of one hand opening a furrow half and inch or more deep, and one leg busted up so the foot was facing the opposite direction it should,” said Hatch. “I was in shock, and others had to grab me and pull me down.” Saucerman and the redoubtable Private Ragland were evacuated, becoming the platoon’s last casualties.

Floyd Pounders had one more sorrowful task to complete before leaving the island. Graves Registration accounted for every fallen scout sniper save one: Sergeant Harry McFall. “It seemed I was the only person who knew where McFall was killed and could remember how to get back to that point,” Pounders said. He led a collection party back to the battlefield of Feb. 25 and quickly found the fallen Marine. “He was on his back. Someone had cut all his pockets and removed his watch, dog tags, and all the identification he had on him. Scavenger hunters! They had taken everything except his clothes.” After lying unburied for 20 days, McFall’s body hardly looked human.

“The only way I could be sure it was Sgt McFall was by the type of clothes he was wearing and that he was in the same place he had fallen earlier,” Pounders said. “His clothes also had laundry marks to identify him.”

In their first and only campaign, the Scout Sniper Platoon, 24th Marines, suffered nearly 80% casualties. They received little recognition, individually or as a unit, for their sacrifices: a few Bronze Stars, many Purple Hearts, and the May 1945 Leatherneck article “Toward the Ridge” by Bryce Walton. The survivors, though, never forgot their role at Iwo Jima.

“Sometimes I felt that we were real workhorses, and then at others, I felt that we were just a few to add to the total number necessary to take a place like Iwo,” Pounders wrote. “Every man there was a hero as far as I’m concerned. No matter what his job was, he helped secure the island, and that was what we were sent to do. If you lived to write about it, well … that was something else.”

Author’s note: Frank Charles Hatch died on March 16, 1989, followed by Robert Floyd Pounders Jr., on March 18, 2020. The last surviving 24th Marines Scout Sniper, Marion Wayne Saucerman, passed away on May 2, 2023, at the age of 97.

The author wishes to thank Joseph Hatch for providing the memoirs of Frank Hatch and Floyd Pounders and for his invaluable assistance with this article.

Author’s bio: Geoffrey W. Roecker is a researcher and writer based in upstate New York. His extensive writings on the World War II history of 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, is available online at www.1-24thmarines.com. Roecker is the author of “Leaving Mac Behind: The Lost Marines of Guadalcanal” and advocates for the return of missing personnel at www.missingmarines.com.