Commitment of a Lifetime: Pineapple Marine Veterans Fulfill Their Oath

By: Kyle WattsPosted on December 15, 2024

In May 2024, a group of Marine officers rallied together for a final time in Las Vegas. The event marked the eighth official reunion these veterans have held over the last 26 years. A tragically dwindling number of attendees, now all in their 80s or 90s, faithfully journeyed to the gatherings, recognizing the opportunities to embrace and reconnect with their brothers are coming to an end. Like Marines of any age who have earned the eagle, globe and anchor, these veterans have felt the immense pride and impact that accomplishment brings. Unlike many of us, however, they have had a lifetime of experience and reflection to understand how the bonds they formed long ago would affect them so deeply. Many of the group remained in the Marine Corps for their entire career, retiring as general officers or colonels. Still more left the Corps as soon as their initial contract ended, finding success in the civilian world. For all, the bond they share reaches back to the early 1960s on the island of Oahu.

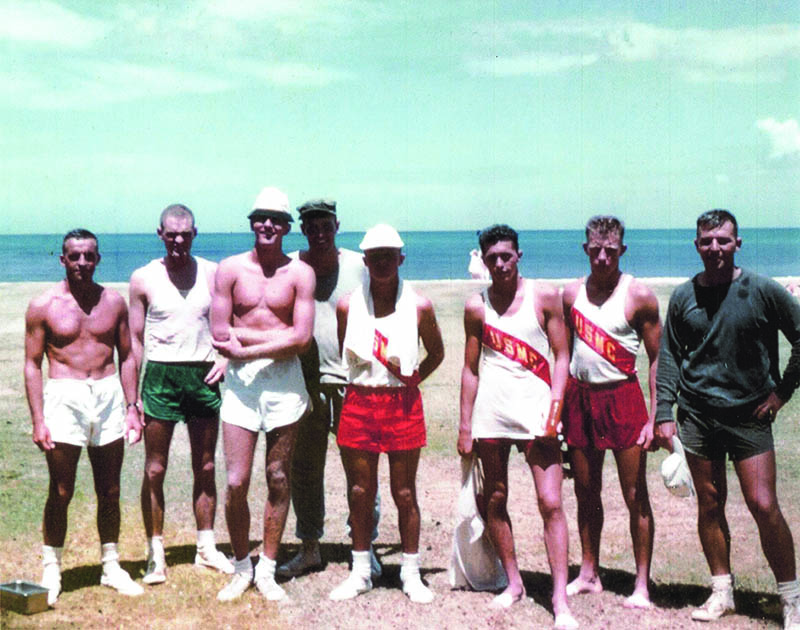

Fresh from The Basic School, the newly minted lieutenants arrived at their first duty station with the “Pineapple Marines” in Hawaii. It was a unique time and place for them to serve together. The nation prepared for large-scale conflict in Vietnam. Meanwhile, the individuals stationed with the 1st Marine Brigade in Kaneohe Bay were isolated from events happening around the world. The single Marines living in the Bachelor Officer Quarters spent every day with each other, some of them for several years. The married Marines settled their families into the cramped base housing and watched their children play all weekend while their wives formed friendships as lasting as their own. Simply being on the island, away from anyone else they knew and insulated from outside communication, forced the Marines and their families to establish a tight-knit community.

“I think the reason we’ve stayed together is because we knew each other before we ever went to combat,” said Edwin Nash, a platoon commander with 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion attached to the brigade. “We trained together, our families knew each other, and that was true for the officers and the enlisted. I knew my NCOs and their families, and they knew mine. That was a tie that I don’t think was found in a lot of other units.”

Everything changed in March 1965. With little notice, the brigade received orders to embark on ships bound for California. Operation Silver Lance, the largest amphibious landing exercise since World War II, was taking place at Camp Pendleton. The generals in charge wanted the Pineapple Marines there for support. Across the island, Marines rushed to settle their families and put their affairs in order, not knowing when they were leaving or how long they would be gone. Wayne Henderson had just joined the brigade as a new artillery forward observer in late February. His wife gave birth to their first child shortly after they arrived.

“They put me on leave so I could take care of my wife and the baby and get them home,” Henderson remembered. “We were still on a waiting list for base housing when I got a call from one of the sergeants in our battery and he said, ‘Hey lieutenant, grab your 782 gear. We’re having a recall.’ I told my wife we were having some sort of drill, and I’d give her a call later to let her know what was going on. That was the last time I got to speak with her before we left. We loaded the ships that night. I left her in a motel with our firstborn, and since we weren’t on base, she had no idea where I went or what was happening.”

The ships departed Pearl Harbor from the south side of Oahu. A few Marines aboard noted their immediate right turn out of Mamala Bay with confusion. For most, reality struck home the following morning.

“I remember waking up on ship and realizing the sun was coming up behind me,” said Nash. “It was supposed to be coming up in front of me! And that’s when I knew we weren’t going to California.”

“Everything started to get filled in that we were going to Okinawa to stage before heading into Vietnam, wherever that was,” said Brian Fagan, a young infantry officer in 1965 who eventually retired as a colonel. “It was all just Southeast Asia or French Indochina to us. But we were so tight that I really think it didn’t matter where the Marine Corps was going to send us. We were going to go, we were prepared to go. We worked hard and were very proud of that. We didn’t know much, but the theme was, ‘Home Alive in ’65.’ We didn’t know how long it would take, but we figured we’d put a couple regiments online, sweep through South Vietnam, and come home.”

The green lieutenants followed the examples set by their leadership once they arrived in the combat zone. Nearly all the senior enlisted and officers were veterans of World War II or the Korean War. At that time, they were not yet called “the greatest generation.” Still, the young Marines stood in awe of them and recognized the place they earned in Marine Corps history.

Starting at the top, Marion E. Carl commanded the brigade. Carl achieved renown as the Marine Corps’ first fighter pilot ace, flying at Midway and Guadalcanal and earning two Navy Crosses and five Distinguished Flying Crosses. Closer to the grunts, battalion commanders such as Joseph R. “Bull” Fisher, a Navy Cross recipient from the Chosin Reservoir, commanded 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines. Alfred I. “A.I.” Thomas commanded the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines leading up to their deployment to Vietnam. A recipient of his first Silver Star from the landing on Iwo Jima, and his next two from the battle at Chosin Reservoir, Thomas played a critical role in preparing his Marines for combat. His successor, Harold D. “Bud” Fredericks, another hero of the Korean War, took the battalion into Vietnam.

“I remember our first night out there in country,” said Kent Valley, a platoon commander serving under Fredericks in 1/4. “We got the troops all dug in, we got the command post all set up, perimeter security was out, and everybody was feeling jumpy. All of the sudden, I heard this, ‘BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!’ Two or three fighting holes around the perimeter just opened up. I don’t know what the hell they were shooting at. I got a call down to the command post, so I ran down there. I reported in and Bud Fredericks looked at me with those steel blue eyes and said, ‘Lieutenant, I haven’t heard this much shooting since the Chosin Reservoir! There’s nobody out there, damnit!’ So, I ran back out and yelled at everybody to cease fire.”

They did not know it at the time, but the brigade’s deployment as a whole unit also proved a unique combat experience. These Marines who lived together and trained together for so long in Hawaii went to war together, where the bonds they had already forged were tested and cemented in the ultimate high-stakes setting. Before their deployment ended, the Marine Corps adjusted its methods of sending fresh troops into combat.

“There was a big change when the Marine Corps suddenly realized that if they didn’t do some personnel changes, the units who went over initially were all going to leave at the same time,” stated Gary Brown, a platoon commander with 2/4 who received two Silver Stars and a Purple Heart, eventually retiring as a brigadier general in 1993. “In my battalion, we had to put together a company and send it off to another battalion. In turn, we received another company of Marines with much later rotation dates. We absorbed them and they became part of the battalion, but it wasn’t like working with the men we had trained with, deployed with, and fought with for five or six months. It made me really appreciate my time with all the Marines I worked with in Hawaii before we deployed.”

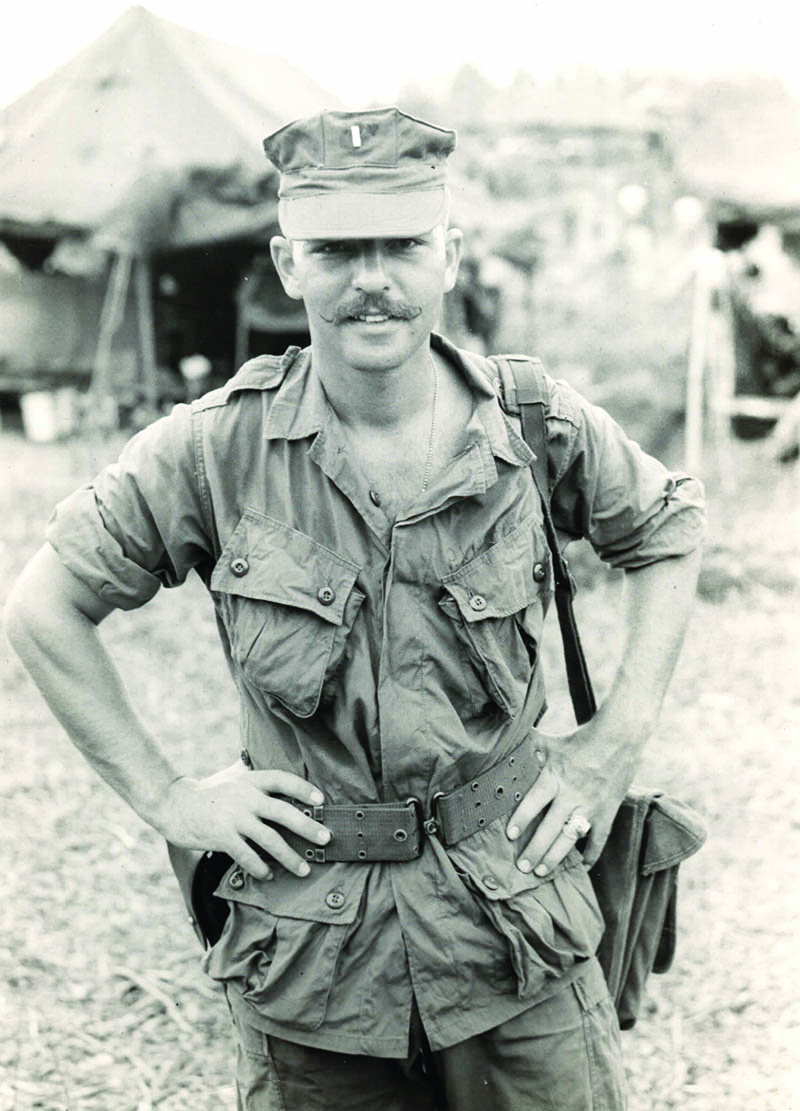

Throughout their time in combat, the quality of the Pineapple Marines was put to the test time and time again. Many highly decorated individuals emerged. The list of men like Gary Brown, who received one or multiple Silver Stars, is impressive in length. Martin Brandtner, then an infantry officer in 1/4, on a later deployment became one of only two Marines from the Vietnam War to earn two Navy Crosses. In 2005, more than a decade after retiring as a lieutenant general, Brandtner wrote a letter to A.I. Thomas, his first commanding officer in Hawaii, crediting Thomas’s leadership as the foundation of his distinguished career.

“For the record, sir, I want you to know that serving under your command in that magnificent battalion was one of the truly great experiences of my life. You provided me and every Marine in that battalion with the greatest example of outstanding leadership that any of us had ever seen—or were ever to see.”

The veterans solemnly remember their brothers who did not return home. They proudly tell stories of men such as Frank Reasoner, a Recon lieutenant who deployed with them. In July 1965, Reasoner led a Recon patrol deep behind enemy lines where the Marines encountered nearly 100 Viet Cong. The lieutenant courageously fought to protect his men as several fell wounded until he was cut down by an enemy machine gun. For his heroic actions and sacrifice, Reasoner posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

The officer group of Pineapple Marines dispersed after their Vietnam deployment ended in 1966. Some like Gary Brown and Martin Brandtner remained on active duty and returned to combat. Others, like Edwin Nash or Kent Valley, moved on to civilian life. Their paths would not converge as a whole again for more than 30 years.

Some of the Pineapple Marines maintained their relationships in small groups. On his first day in the Marine Corps at TBS, Kent Valley met another brand new lieutenant named Ed Roski. The two immediately bonded. They went through training together, arrived in Hawaii together, deployed to Vietnam together and left active duty together. During Operation Starlight in August 1965, Roski was wounded multiple times, receiving two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star. In the civilian world, Roski joined his father’s real estate company in California in 1966 and brought Valley on as part of the team. Roski eventually took over the company and, over the last 60 years, transformed it into one of the largest, privately held business park development companies in the nation. He is also co-owner of the Los Angeles Lakers and the Los Angeles Kings.

Valley remembers the first Gulf War as his initial motivation for reconnecting with more veterans from their original Hawaiian group. Images from the conflict played on TV, featuring senior Marines such as Robert B. Johnston, then a major general serving as Norman Schwarzkopf’s Chief of Staff, and Michael Myatt, the brigadier general in command of the 1st Marine Division and a Silver Star recipient during his time as a lieutenant in Vietnam. Valley recognized the faces as two young officers who were with him in Hawaii.

“Desert Storm was the first time after I got out of the Marine Corps that I really thought about it,” Valley said. “Seeing General Myatt with his Marines, watching Bob Johnston debrief the nation. I called Ed up and said, ‘oh my gosh, we’ve got a bunch of our guys who are running this thing right now.’”

Another small group of Pineapple Marines, Pete Paffrath, John Martin, and Lynn Terry, reminisced about their Marine Corps experiences over the years during an annual backpacking trip in the High Sierra. In the late 1990s, they decided to call some men with whom they had served about a reunion. Paffrath, then an IBM executive, called Roski, who was intrigued by the idea and said, “I own a hotel and casino in Las Vegas. Let’s have it there, and I’ll host the event.”

The Pineapple Marines finally gathered for the first time in 1998. Forty-five veterans attended the inaugural reunion, many with their wives, hosted and funded by Roski. All young men the last time they saw each other, the veterans were shocked by the outstanding levels of success their peers had found in every walk of life. Six became Marine Corps general officers, with many more retiring as colonels. Others, like Roski, found success in the business world; with one becoming CEO of two fortune 500 companies and another founding a multi-billion dollar medical supply company. One became the deputy director of the CIA, while another served as the chief legal counsel for a global pharmaceutical and medical device company. They were teachers, authors, physicians, psychotherapists, lawyers, ranchers; their lives after the Marines as varied as their origins before the Corps assembled them all in Hawaii.

“The number of guys and their wives who are giving back to society, doing something beyond themselves, is over the top,” said Father John Martin, an infantry officer who now serves as a Jesuit priest in California. “That speaks to the basic goodness of these men. I am always energized seeing that goodness.”

Many of the veterans entered the reunion hesitantly, having kept their demons from Vietnam locked away for 30 years. If ever a place could exist where those memories might be safely unearthed, the reunion seemed hopeful. Everyone discovered the decades-long interruption in their friendships meant little.

“There’s something about going to war together that is unlike anything else,” reflected Nash. “You spent time doing something together when you were at the top of your game. You got to know these people in a way that you don’t get to know anybody else. You put more emphasis on what you shared together than you do on your differences, and that’s not normal. Everyone always wants to get all upset about differences. So, when you get back together with these folks, it’s like you were there yesterday. It’s like you can almost finish a sentence you started years ago.”

“For a long time, there were no reunions,” stated Henderson. “We just sort of ducked and covered and didn’t talk about Vietnam because you never knew what you were going to encounter. So, at first, the reunions were a little tentative, but ever since they have been so uplifting and life-affirming. Marines have very low-maintenance relationships. We may not see each other for a couple years, but we always pick up right where we left off. It goes unspoken, but we know how deeply we love and care for each other.”

The Marines attending the first reunion found their rekindled relationships just as important and perhaps even more impactful now in retirement than the friendships they formed in Hawaii and Vietnam in the 1960s. In the years since, the Pineapple Marines have held a total of eight reunions, seven graciously hosted in Las Vegas by Roski, and one at the Marines’ Memorial Club in San Francisco, Calif.

“The Pineapple Marines is the only reunion group I have ever attended,” said Lloyd Brinson, a former artillery officer and retired teacher and school administrator. “I lived in denial about Vietnam for nearly 30 years. These reunions have helped me finally settle the beasts that have been running around in my life for so long.”

“There is a lot of storytelling at the reunions, stories of what people lived through in Vietnam,” said Paffrath. “Things that people had questions about that they just wanted to talk to someone else about. I think that has been very therapeutic.”

The Pineapple Marines revere their time together in Hawaii for bringing them all together. Their bond, however, stems not from the island. Their connection, exponentially more important as the decades have passed, comes from the title they earned as Marines. Whether they spent their entire career wearing the uniform, or left active duty after coming home from Vietnam, all find their sense of identity equally tied to the Corps.

“My Marine Corps experience took a guy who was less than outstanding, and probably ended up not outstanding, but at least I could walk among people who were outstanding without looking totally out of place,” said Bob Morrison, a Silver Star recipient who is the retired CEO of Quaker and Kraft Foods. “It gave me a great deal of confidence. It was the most important four years of my development. I really grew up, learned to trust people, and hopefully learned to be trustworthy.”

“The Marine Corps imbues something inside of you that changes you, and any time you meet another Marine, even if you didn’t serve with them, there’s some kind of simpatico thing going on,” said Paffrath. “You can call it a fraternity if you want, but it’s more like a religion.”

Today, the Pineapple Marines support active-duty servicemembers and veterans younger than themselves through numerous nonprofit organizations or events in their local areas. To them, they can never give back enough to account for everything they have gained from their time in the service and the brotherhood they have perpetuated. The Pineapple Marines have dedicated their lives to fulfilling the oath they took when accepting their commission so long ago.

“It’s a commitment to integrity,” reflected Father Martin. “That is a commitment not fulfilled in any four-year contract. It is something you work on your entire life.”

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-13. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.