An Unnecessary Victory? Peleliu Assault Fraught with Issues

By: Maj Skip Crawley, USMCR (Ret)Posted on August 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: What’s old is new again. September marks 80 years since Marines fought and died on Peleliu. The island was taken as part of the Allies’ island hopping campaign during World War II.

Peleliu has once again become a critical element in U.S. strategy—this time due to its important location with respect to major power competition with China. Due to the island’s renewed significance, Peleliu’s airstrip has been restored. Read about the recent landing of a Marine Corps KC-130 on the island on page 13.

The September 1944 Battle of Peleliu is not as well-known as other battles in the World War II island hopping campaign. Perhaps because, as one survivor recalled in Colonel Joseph H. Alexander’s book “Storm Landings,” “Everything about Peleliu left a bad taste in your mouth.”

By the time the 1st Marine Division landed on Peleliu, the reason for taking the island had been rendered moot by events elsewhere. Worse, the poor execution of the battle by the senior leadership of the 1st Marine Division bled the division white. Failing to understand that the Japanese were employing a new defensive doctrine that had been designed with the goal of inflicting maximum casualties rather than attempting to throw an amphibious assault back into the sea, Major General William Rupertus and his senior subordinates continued to employ the tactics that had worked in the division’s previous battles at Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester. While the decision to take Peleliu didn’t rest solely with MajGen Rupertus, he and the senior leadership of 1stMarDiv were responsible for draining the division’s resources by launching frontal assaults against well dug-in Japanese fortifications. In the end, tactical command of 1stMarDiv was replaced by the Army’s 81st Infantry.

Strategic Background

Prior to World War II, the Navy had developed War Plan Orange, the Navy’s strategy for advancing across the Central Pacific to relieve the Philippines and to fight and win a modern-day Jutland against the Imperial Japanese Navy in the western Pacific. The plan ended with a blockade of the Japanese home islands to ensure a complete U.S. victory. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy spent the first two years of the war on the defensive or conducting a slow, methodical advance up the Solomon Islands chain. But on Nov. 20, 1943, the Central Pacific offensive began.

Under the strategic direction of Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) and Commander in Chief Pacific Ocean Areas, and the tactical command of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Commander, 5th Fleet, troops landed at Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. From that point on, the Central Pacific offensive was very successful, capturing Kwajalein and Roi-Namur in the Marshall Islands (Jan. 31-Feb. 7, 1944) and Saipan, Guam and Tinian in the Mariana Islands (June 15-Aug. 10, 1944). Using new and innovative carrier tactics, Task Force 58 (TF 58), the Fast Carrier Task Force of the 5th Fleet, would isolate an island or group of islands from Japanese air and sea attack, while the amphibious ships of the V Amphibious Force carried the Marines and soldiers of V Amphibious Corps to the beaches, who conducted the actual landings.

However, following the capture of Guam in August 1944, the Central Pacific offensive was put on hiatus to focus American resources on supporting General Douglas MacArthur’s return to the Philippines. To that end, ADM Spruance relinquished command to ADM William “Bull” Halsey, and the 5th Fleet was immediately redesignated the 3rd Fleet. TF 58 became TF 38, and the V Amphibious Force became III Amphibious Force. The 3rd Fleet also contained the III Amphibious Corps, which had been established in April 1944 and consisted of 1stMarDiv and 81st Infantry Division and was commanded by Marine aviator MajGen Roy S. Geiger.

MacArthur’s Return to the Philippines and Nimitz’s Refusal

To Cancel Peleliu

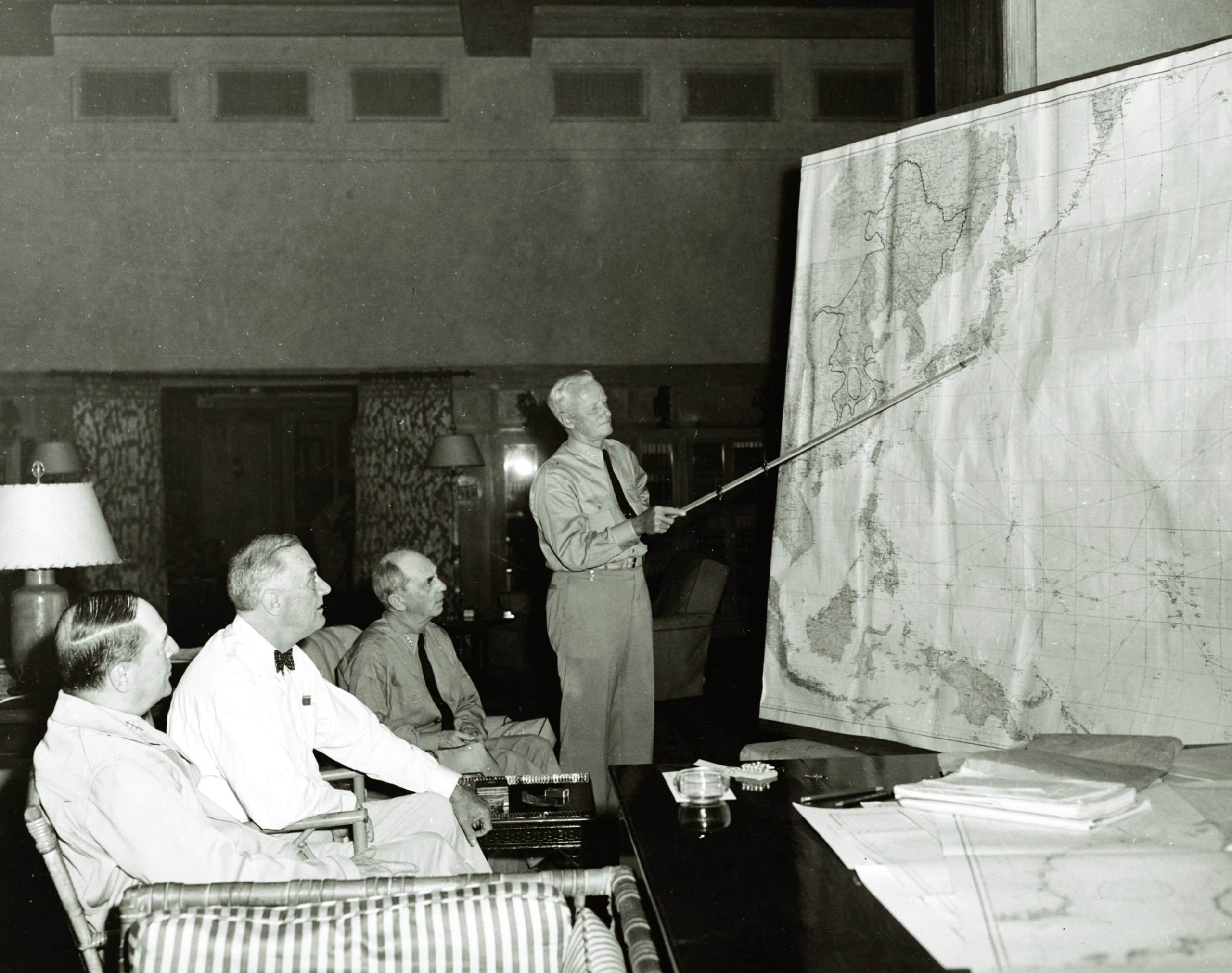

Following his defeat in the Philippines and his subsequent arrival in Australia in March 1942, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief, Southwest Pacific Area, was determined to return there. After much debate, including a presidential visit to Pearl Harbor in July 1944 to hear MacArthur’s proposal to take the Philippines and Nimitz’s proposal to take Formosa (present-day Taiwan), the joints chiefs of staff granted MacArthur his wish.

MacArthur’s original plan was first to take Mindanao, the southernmost island in the archipelago, then Leyte, a large island in the central Philippines, and finally, in the culmination of the campaign, Luzon, the northernmost and largest of the Philippines—where Manila, the capital, was located. But ADM Halsey, commanding his newly redesignated 3rd Fleet, recommended a radical change in the plan to Nimitz: “Nimitz had promised Douglas MacArthur in the presence of President Roosevelt the previous summer that he would support his adjoining theater commander’s long-anticipated return to the Philippines,” writes Colonel Joseph Alexander, USMC (Ret) in his book “Storm Landings: Epic Amphibious Battles in the Central Pacific.”

“MacArthur worried about the threat to his right flank in advancing from New Guinea to Mindanao posed by Japanese airfields on Peleliu in the Palaus and on Morotai in the Moluccas. The two commanders agreed to attack both islands on 15 September, MacArthur against Morotai, Nimitz against Peleliu.”

According to Alexander, “Abruptly, at [the] eleventh hour, came a thunderbolt from Halsey. In a flash precedence, top secret message to Nimitz, intended for the Joint Chiefs, Halsey recommended major revisions to the conduct of the Pacific War. While rampaging through the Philippines with his fast carrier task forces, Halsey had found surprisingly light opposition. In his view, the door to the central Philippines lay open (‘this was the vulnerable underbelly of the Imperial Dragon’). His message suggested mind-boggling changes: cancel the invasion of Mindanao altogether; strike instead at Leyte, and do so two months early; cancel the entire Palaus operation; redeploy the Army’s XXIV Corps (scheduled to seize Yap and Ulithi) to MacArthur for Leyte.”

The joint chiefs responded to Halsey’s recommendations with unusual alacrity and unanimity. MacArthur was authorized to bypass Mindanao and go directly to Leyte, but they left to Nimitz the decision to execute the original plan and take Peleliu as scheduled or cancel it. Nimitz chose to stick with the original plan. Unfortunately, the reason for taking Peleliu—to guard MacArthur’s right flank as he attacked Mindanao—was no longer necessary. As retired Marine Colonel Dick Camp wrote in his book “Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu, September 15-21, 1944,” “Peleliu was a battle that should not have happened. Initially planned to support MacArthur’s return to the Philippines, the bloody assault on this small seven-square-mile coral island was declared to be unnecessary by ADM William F. ‘Bull’ Halsey, Jr., after his fast carrier strike force found the Philippines ripe for the picking. He recommended canceling the operation but was overruled by Fleet Adm. Chester Nimitz—a controversial decision that signed the death warrant for thousands of Americans and Japanese.”

Why did Nimitz choose to execute the landing on Peleliu as scheduled? He didn’t record the reasons why in a diary, so his motives are open to conjecture. Likely there were several reasons which could’ve justified his decision. First of all, advanced operations were already in progress for the scheduled Sept. 15 assault when Halsey’s message was received on Sept. 13. Nimitz was concerned that if he called off Peleliu, the Japanese would claim they had defeated an American amphibious assault and thrown the Marines back into the sea. Second, as Alexander states, CINCPAC had worked hard to get Peleliu and adjoining islands forces under way; reversing that momentum would be costly and bad for morale. Lastly, according to author Jim Moran’s “The Battle of Peleliu: Three Days that Turned into Three Months,” Nimitz stated that “the invasion forces were already at sea and the commitment made, making it too late to call off the invasion.”

Nimitz should have been more concerned about the reality of heavy losses than about the Japanese scoring a propaganda victory. The Japanese claimed numerous outlandish victories and successes throughout World War II, including claiming to sink multiple carriers of TF 38 when in fact TF 38 suffered little or no damage. Canceling an operation the size of Peleliu would be difficult but not impossible.

While Nimitz’s failure to cancel the Peleliu operation was wrong, the senior leadership of 1stMarDiv would make a bad situation much worse. There were also new Japanese tactics that confounded MajGen Rupertus and his senior subordinates.

A Change of Japanese Tactics: “Fukkaku Positions”

The original Japanese doctrine for defending against American amphibious assaults was to defeat the assault at the water’s edge.

In the book “Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa,” by Col Joseph Alexander, “The Japanese planned to defend Betio [the island of the Tarawa atoll that 2ndMarDiv assaulted] at the water’s edge, a static vice mobile tactical philosophy that would characterize the defenses of some of the subsequent, larger islands in the Central Pacific. … [Japanese] ‘Battle Dispositions’ of October 1942 contained the directive, ‘Knock out the landing boats with mountain gun fire, tank guns and infantry guns, then concentrate all fires on the enemy’s landing point and destroy him at the water’s edge.’ Employment of this water’s-edge defense by Navy units was so prevalent in 1943-1944 that one can assume a central directive of this nature emanating from the Navy Division, IGHQ [Imperial General Headquarters].”

Dying for the emperor was considered a privilege for those Japanese who were immersed in the bushido culture and revered their emperor as a living deity. With an emphasis on the offensive, such as banzai charges, this defensive doctrine played to the strengths of Japan’s army. But after failing to stop the Marines at the water’s edge at Tarawa, Roi-Namur, Saipan, Guam and Tinian, the Japanese fundamentally changed their tactics at Peleliu.

Acknowledging the reality that they couldn’t defeat an American amphibious landing at the water’s edge, they chose to conduct a prolonged campaign of attrition designed to bleed the landing force as much as possible in hopes that the American people would be demoralized by the heavy casualties and agree to a negotiated peace.

What were these specific tactical changes? Alexander in “Storm Landings” explains:

“Imperial General Headquarters in August 1944 published “Defense Guidance on Islands,” which reflected the bitter lessons of the Marianas, recommended defense in depth, and advised against ‘reflex, rash counterattacks.’ Army field commanders noted the transition from seeking the elusive ‘decisive engagement’—ludicrous in the absence of air or naval superiority—to a much more realistic policy of ‘endurance engagement.’ Policy statements began to include the phrase ‘Fukkaku positions,’ defined as underground, honeycombed defensive positions.”

These new defensive tactics implemented by the Japanese leadership on Peleliu were greatly enhanced by the island’s forbidding terrain. According to “Storm Landings” by Alexander,

“Peleliu is barely 6 miles long by 2 miles wide and shaped like a lobster claw. The airfields—the main complex in the south and the fighter strip under construction on Ngesebus in the north—lay fully exposed in flat ground. But along the northern edge lay the badlands—a jumble of upthrust coral and limestone ridges, box canyons, natural caves, and sheer cliffs. The natives called this forbidding terrain the Umurbrogal; the Japanese named it Momoji. The Americans would call it Bloody Nose Ridge. But here was a critical intelligence failure. Dense scrub vegetation covered and disguised the Umurbrogal before the bombardment began. Overhead aerial photographs failed to reveal this critical topography to U.S. analysts. That’s why General Geiger [the commander of the III Amphibious Corps,] was so astonished on D-day to see such dominant terrain overlooking the airfield and beaches. [IGHQ sent] mining and tunnel engineers to Peleliu to help build the defenses. Within months the forbidding hills and cliffs were honeycombed with more than five hundred caves. Some were five or six stories deep. Some had sliding steel doors to protect heavy weapons. All had alternate exits. All were mutually supporting by observed fire. Here was a classic Fukkaku position defense.”

Alexander points out a particularly imaginative tactic the Japanese used. After the Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) removed the mines and obstacles leading to the beach, the Japanese had swimmers plant antiboat mines and had, in effect, underwater kamikazes:

“UDT frogmen removed hundreds of antiboat obstacles from the approaches to the landing beaches during dangerous daylight operations. But [Colonel] Nakgawa [the main architect of the Japanese defenses on Peleliu,] had his own stealth swimmers. These he sent out the night before D-Day to plant rows of horned antiboat mines 150 yards from the beach. This was a stroke of brilliance, but it failed in execution because Nakagawa’s swimmers in their haste neglected to pull the safety pins from most of the mines. Otherwise, the results could have been disastrous for the landing force. Postlanding sweeps found a large number of these powerful mines with their contact horns crushed by American LVTs, intact but harmless.

“Nakagawa, alerted to the American’s intended beaches by the UDT activity, endeavored to further disrupt the assault by stationing suicide teams in the water along the reef prepared to serve as ‘human bullets’ against tanks and armored amphibians. He also tried to pre-position drums of fuel along the reef with which to ignite a wall of ‘fire along the seawater.’ None of these innovations worked, but Nakagawa’s other plans for sacrificing one battalion to ‘bleed’ the landing succeeded. Aircraft bombs planted vertically in the sand with special contact fuses served as awesome mines. His camouflaged positions of ‘passive defense’ maintained their cover until the initial Marines had stormed inland—then emerged to shoot the next echelons in the back. All this—while Nakagawa’s main force lay in deep shelter in the Umurbrogal.”

Peleliu was going to be a tough nut to crack, no matter who was taking it.

1stMarDiv on the Eve of Peleliu

Fitting for “soldiers of the sea,” 1stMarDiv was “born at sea” on Feb. 1, 1941. As author Camp explains, “The date of its designation made it the first division in Marine Corps history and earned it bragging rights among those divisions that followed,” hence its nickname, “The Old Breed.”

“If I had had an option—and there was none, of course—as to which of the five Marine divisions I served with, it would have been the 1st Marine Division,” writes Private First Class Eugene B. Sledge in his “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa.”

“Ultimately, the Marine Corps had six divisions that fought with distinction in the Pacific. But the 1st Marine Division was, in many ways, unique. It had participated in the opening American offensive against the Japanese at Guadalcanal and already had fought a second major battle at Cape Gloucester, north of the Solomon Islands. Now its troops were resting, preparing for a third campaign in the Palau Islands. …

“Other Marines I knew in other divisions were proud of their units and of being Marines, as well they should have been. But … the 1st Marine Division carried not only the traditions of the Corps but had traditions and a heritage of their own, a link through time with the ‘Old Corps.’ ”

As Alexander says in “Storm Landings,” “The 1st Marine Division had fully earned its spurs and its Presidential Unit Citation at Guadalcanal.”

1stMarDiv had proved itself from the early days of the war and was justifiably proud of its combat record. But what about its Commanding General? For Peleliu, the “Old Breed” would be led by MajGen William H. “Bill” Rupertus. Rupertus’ distinguished career included service in Haiti and China during the 1937 Sino-Japanese hostilities. A member of the Marine Corps shooting team, he was a strong advocate for marksmanship training.

In “Commanding the Pacific: Marine Corps Generals in World War II,” Stephen R. Taaffe states:

“Rupertus was perhaps the Marine Corps’ most controversial World War II division commander … Rupertus’ pettiness, selfishness, and mercurial temperament made his ambition seem cloying and vindictive. His harsh opinions, tendency to play favorites, and obvious moodiness, and ostentatious living while in the field also alienated many. … Geiger eventually questioned Rupertus’ basic competence.”

Following the Cape Gloucester campaign, 1stMarDiv was supposed to recuperate on the island of Pavuvu from the rigors of the previous campaign. Pavuvu proved to a be less than idyllic place to rest. The island had been the site of coconut plantations owned by Lever Brothers; the soap company used coconut oil in their products. When the war began, the plantations were quickly abandoned, leaving behind untended groves of coconut palms which continued to produce fruit. Not only did the rotting mess of coconuts smell terrible, they attracted enormous rats.

While Rupertus was not responsible for the choice of Pavuvu as their R&R camp, he lived better then his Marines did. Taaffe wrote that “there [at Pavuvu] the leathernecks established a squalid camp amid rotten coconuts, omnipresent rats and crabs, and plenty of mud. Rupertus did not share his men’s discomfort. For one thing, his quarters were so noticeably luxurious by Pavuvu standards that people commented on it.”

Personality aside, Rupertus’ major failing as a division commander prior to Peleliu was his failure to realize the “storm landings” of the Central Pacific required new tactics and a fresh way of thinking. Failure to learn from others and prepare the division adequately for the Peleliu campaign falls upon Rupertus’ shoulders.

According to Jeter A. Isely and Dr. Philip A. Crowl, authors of the seminal “The U.S. Marines And Amphibious War: Its Theory, And Its Practice In The Pacific,” “The division had had ample experience in jungle warfare … but it needed to be reoriented toward a new type of fighting which the terrain of Peleliu would demand.”

Alexander agrees; the veteran Marines of 1stMarDiv “were likely the best jungle fighters in the world. But the division also had some shortcomings. While their collective fighting spirit would forever sustain them in combat, the Old Breed would need more than jungle fighting skills to prevail in the cave and mountain warfare waiting [for] them at Peleliu. Also, this would be the division’s first major storm landing. For all the subsequent savagery of the fighting for Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester, the Old Breed had never executed a landing against major opposition in prepared defenses. Rupertus did little to close the gap. While the rest of Fleet Marine Forces Pacific leapt at the opportunity after Tarawa to convert their LVTs into tactical assault vehicles, Rupertus demurred. He preferred their original employment as logistic support vehicles. Nor did Rupertus put much stock in naval gunfire planning. Geiger was shocked to discover that the division went into combat at Peleliu without a designated naval gunfire officer on its general staff. Nor was Geiger impressed with the division’s proposed landing plan: three regiments abreast, only one battalion in division reserve, no interest in asking to earmark one of the Wildcat regiments [the 81st Infantry Division] for backup.”

Having just come from the Guam campaign where nearly two weeks of shelling proceeded the landing, Lieutenant General Geiger was aghast at Rupertus’ decision to have only two days of preinvasion naval gunfire and arranged for a third day. The division’s landing plan also made little provision for maintaining the momentum of an amphibious assault—an important aspect of landings within the Central Pacific. With only a single battalion in reserve and Rupertus’ refusal to utilize a regiment from the 81st Infantry Division that was offered for assistance, his Marines would be hard pressed to maintain their momentum after they landed.

If there was any doubt that Rupertus’ thinking was not grounded in reality, his comments prior to Peleliu concerning his estimate of the duration of the battle settle all doubt. Sledge has this to say:

“As for the upcoming operation, Rupertus was openly optimistic that it would be quick. He wrote to Vandegrift, ‘There is no doubt in my mind as to the outcome—short and swift, without too many casualties.’ He was wrong.”

Alexander in “Storm Landings” has this to say: “‘Rough but fast,’ he predicted to his subordinates and the handful of combat correspondents gathered on his flagship. ‘We’ll be through in three days. It might take only two.’ Throughout the landing and the battle ashore Rupertus would exert unholy pressure on his conquest. He expected a hot fight but assumed a steady offensive would crack the enemy’s resolve, leading shortly to the traditional mass banzai charge and ‘open season’ slaughter. Then it would be a simple matter of mopping up. The Army could do that.”

Rupertus’ optimism spread among the men. And to make matters worse, he had broken his ankle during rehearsal for the battle, which limited his mobility. During the fighting, he was never able to observe his Marines up close.

“Geiger was … very unhappy to learn the true extent of his injury,” Taaffe writes in “Commanding the Pacific.” “During late August rehearsals at Cape Esperance, [Brigadier General] Oliver Smith [, the Assistant Division Commander,] led the leathernecks ashore and established the division’s command post because Rupertus could not get out of his boat. Geiger arrived and asked Smith for Rupertus’ whereabouts. When Smith told him, Geiger said, ‘If I had known I’d have relieved him.’ ”

To recap, prior to assaulting Peleliu, 1stMarDiv was a very effective combat unit that had proved itself in one of the Marine Corps’ epic battles and had done a yeoman’s service since. But the Marines of the division were headed into a battle unlike anything they had experienced in the South Pacific—and with a Commanding General that did not comprehend the type of battle in which they were about to engage.

1stMarDiv (Almost) Takes Peleliu

Taaffe’s description of Peleliu in “Commanding the Pacific” gives a very good and succinct view of the Peleliu campaign for Rupertus and the 1stMarDiv:

“On the morning of 15 September, the Marines encountered punishing fire when they came ashore on Peleliu’s southwestern coast. Despite these losses, the veteran leathernecks pushed inland against increasingly stiff opposition that included tanks. On the northernmost beaches, Col Lewis “Chesty” Puller’s 1st Marine Regiment suffered especially high casualties …

“From that point Peleliu degenerated into a prolonged and gruesome battle of attrition for the Marines. They made some initial progress but suffered heavy casualties. The 5th Marine Regiment overran the airfield while … [the] 7th Marine Regiment secured the southern portion of the island.”

The problem was twofold: failing to adapt to the new Japanese tactics, and the Umurbrogol. As Alexander in “Storm Landings” explains:

“The real tragedy of Peleliu occurred during the first week, when General Rupertus and Colonel Puller believed they faced a linear defense along the perimeter of the nearest high ground, the kind of positions they could surely penetrate with just one more offensive push. As a result, for all their undeniable bravery, the 1st Marines sustained appalling casualties and had to be relieved by a regiment of Wildcats (at Geiger’s insistence) six days after the landing. Maj Ray Davis’s 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, suffered most grievously, losing 70 percent of their number, their line companies reduced to a corporal’s guard.”

Concerning the Umurbrogol, Taaffe writes, “The problem was rooting the Japanese out of their stronghold in the Umurbrogol ridges in the north. These deep, wooded, and coral-covered ridges were tailor-made for defense. It was almost impossible to spot the snipers and infiltrators making life miserable for the leathernecks. The terrain offered no secure footing and no place to dig in. Exploding artillery and mortar shells turned the omnipresent coral into deadly shrapnel.”

As Taaffe says, “Peleliu was hard on everyone.” But how was Rupertus holding up? He wasn’t.

“He had believed, and promised, that his Marines would secure Peleliu quickly. As September turned into October and the Marines continued battering the Umurbrogol ridges, without much success, Rupertus began to unravel psychologically. He remained publicly optimistic, but privately he had no idea how to win the battle anytime soon … At one point Rupertus put his head in his hands and said to a staff officer, ‘This thing just about got me beat.’ When Harris, commander of the 5th Marine Regiment, visited division headquarters on 5 October, he found Rupertus in tears. ‘Harris,’ said Rupertus, ‘I’m at the end of my rope. Two of my fine regiments are in ruins.’ ”

How was the iconic Puller doing? Not much better. Taaffe writes:

“Unlike Rupertus, Geiger toured the front frequently to assess the battle and keep his subordinates on their toes. Although he became increasingly concerned with the 1st Marine Division’s casualties and lack of progress, he hesitated to interfere with Rupertus’ prerogatives as commander. On 21 September, Geiger visited Puller at the 1st Marine Regiment’s rudimentary command post. No one doubted Puller’s fearlessness and aggressiveness, but he often simply threw his leathernecks at the Japanese defenses without much tactical finesse or fire support. Moreover, he suffered from obvious exhaustion and struggled to explain the current situation coherently. Puller was, however, adamant that he did not need any assistance to achieve his objectives. A skeptical Geiger then drove to the 1st Marine Division’s headquarters and examined Puller’s casualty reports. He learned that the regiment had sustained 1,672 dead and wounded on Peleliu. Indeed, one of its battalions had lost 71 percent of its strength. Geiger informed Rupertus that Puller’s outfit was finished and insisted on its relief and replacement by one of the regiments from the Army’s 81st Division, which had recently overrun Angaur. Rupertus strongly disagreed. Given his distaste for the Army, he abhorred the thought of its soldiers ending a job that the Marines had started. He insisted that the Marines could wrap up the operation in a day or two. Not persuaded, Geiger issued the necessary orders. On 23 September, what was left of the 1st Marine Regiment pulled out and made way in the line for the Army’s 321st Regiment.”

It’s no surprise that Geiger ordered Rupertus to turn the battle over to the Army’s 81st Infantry Division and have them complete the operation.

One Bright Spot: Close Air Support

Since Marine ground forces had left the South Pacific theater, they had not been supported by their brethren in the air, as Marine Corps doctrine and desire wanted. Since the Marine Corps lacked the heavy artillery that the Army had, they were more dependent upon air support. The problem was that prior to Peleliu, islands were out of range of Marine air. But Peleliu changed that:

“General Geiger made sure that MAG-11 [Marine Air Group 11 with F4U Corsairs] provided the kind of ‘flying artillery’ that amphibious planners had envisioned before the war,” writes Alexander. “This was close air support at its finest. Marine Corsairs would take off from Peleliu’s airstrip and not even raise their landing wheels. In 15 seconds they would be over the target, dropping their belly ordnance, then circling to land and re-arm. Indeed, the first bomb delivered sprayed steel shrapnel onto the airfield, a mere thousand yards behind the point of impact.”

Conclusion

Peleliu was an island that did not need to be taken. The original purpose of taking Peleliu—to guard MacArthur’s right flank as he took Mindanao, the southernmost island of the Philippines—evaporated when the decision was made to go directly for the island of Leyte in the middle of the archipelago.

In “Commanding the Pacific,” Taaffe asserts, “Although high-ranking Marine officers could not be held accountable for Peleliu’s selection, they bore considerable responsibility for the battle conducted. As 1st Marine Division commander, Rupertus deserved censure for underestimating the operation’s difficulties, undertaking an assignment for which he was not physically fit, and using and tolerating Puller’s unimaginative tactics. …

“The price for this Pyrrhic victory was steep. The battle cost the 1st Marine Division 1,124 dead, 5,024 wounded, and 117 missing, for a total of 6,265 casualties. The division suffered so much damage that it took months to rebuild it. Small wonder that one Marine officer said, ‘[S]omebody forgot to give the orders to call off Peleliu. That’s one place nobody wants to remember.’”

Indeed it was.

Author’s bio: Maj Skip Crawley, USMCR (Ret) was an Infantry Officer who was assigned to 1st Battalion, 7th Marines during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. He is a frequent contributor to Marine Corps Gazette.