Nicaragua 1928: The Rio Coco Patrol

By: Maj Allan C. Bevilacqua, USMC (Ret)Posted on May 15, 2025

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the September 2016 issue of Leatherneck Magazine.

“Due to all the rains, the river is so high that our boats have to go along close to the bank, wending their way between and under trees. It is a common thing to have to cut one’s way through the limbs. The result is that all day one is busy brushing off ants—worms—and bugs of all disciplines, most of whom bite.”

—Capt Merritt A. Edson, USMC, Nicaragua, August 1928

As early as the mid-nineteenth century, the Central American country of Nicaragua had been constantly torn between two political factions, Conservatives and Liberals, each striving for national supremacy. Conservatives could be described as devout Roman Catholics who believed in traditional Hispanic forms of family and society, while Liberals practiced an almost anti-clerical secularism and an increasingly aggressive form of Euro-socialism. Their conflicts at the ballot box frequently erupted into armed confrontation.

The year 1928 was an election year in Nicaragua, and Nicaraguan elections were not passive affairs. The election of 1928 promised to be even more explosive than most, which were explosive enough in their own right. Into the volatile mix of Conservatives and Liberals was thrown the human incendiary device of Augusto Nicolas Calderon Sandino. A complex blend of ardent Nicaraguan patriot and fire-breathing Marxist revolutionary dedicated to the armed overthrow of the government, Augusto Sandino had openly declared his intention to disrupt the elections and seize power by force.

As a countermove, Nicaragua’s interim president, Adolfo Diaz, requested that the elections be monitored by United States Marines. U.S. President Calvin Coolidge was less than enthusiastic at the prospects of such an involvement, but under the terms of an agreement negotiated between Conservatives and Liberals by Special Envoy Henry L. Stimson, the President consented. The stage was set for a collision between Marines and Sandino’s followers, “Sandinistas.” That collision would take place in eastern Nicaragua, for centuries the home of the Miskito Indians.

The Miskito

The Miskito prided themselves in never having been subjugated by early Spanish adventurers. Neither had they been assimilated into Nicaraguan culture, being more than determined to remain in their dense jungle domain, a nation within a nation, viewing Nicaraguans as Spaniards. They were the absolute masters of a vast region of rainforest, second in its immensity only to the Amazon, with almost no roads and few trails. In their extremely remote area known as “The Frontier,” the Miskito, expert boatmen without peer, roamed freely along waterways that would have defeated anyone else. Even the Rio Coco, a raging torrent all year, but especially during the rainy season, gave them no fears. From its source in the province of Nueva Segovia, Augusto Sandino’s stronghold in Nicaragua’s Northern Highlands, the Rio Coco flowed almost 500 miles, its lower reaches forming part of the international boundary between Nicaragua and Honduras, before reaching the sea north of Puerto Cabezas.

It wasn’t the Rio Coco’s length that made it such a formidable barrier. It was the river’s very nature that made it so daunting. There was nothing gentle and meandering about the Rio Coco. Every foot along the way the constantly decreasing elevation of the region forced the Rio Coco along at an ever faster rate of flow. Going upstream against that current was extremely difficult at best. During the summer rainy season, when the eastern region of Nicaragua endured as much as 300 inches of rain, the Rio Coco was capable of rising 1 foot each hour. Taking the Rio Coco head-on was a job for only the most skilled watermen.

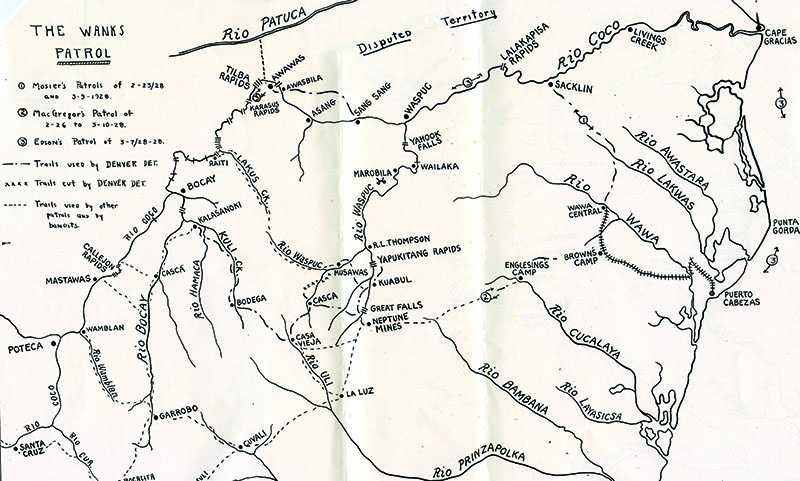

Taking the Rio Coco head-on at the height of the rainy season, with the river at flood stage, was exactly what Captain Merritt A. Edson, USMC, intended to do. As commander of the Marine Detachment, USS Denver (CL-16), Edson had brought his entire detachment ashore at Puerto Cabezas in January 1928. As directed by Major Harold Utley, USMC, the officer in command of Nicaragua’s Eastern District, Edson and Denver’s Marines began conducting local security patrols in response to intelligence reports indicating possible infiltration by advance elements of Sandino’s forces. In June, Edson’s small command was increased with the addition of the Marine Detachment, USS Rochester (CA-2).

Why wait for Sandino to bring major elements from the north, Edson reasoned. Why allow Sandino to exercise the initiative? Why not hit Sandino from the blind side, what he thought was his secure eastern flank, before he was able to make good his intention to carry the conflict to the Eastern District? How? By driving some 370 miles directly up the Rio Coco to the town of Poteca, Sandino’s best potential staging base, checkmating Sandino’s move before he could make it.

Edson’s Proposal

Confident that he could beat Sandino to the punch, even faced with the racing waters of the Rio Coco, Edson approached Maj Utley with the proposal. During the months they had been associated, Maj Utley had become so impressed by Merritt Edson’s aggressiveness, determination and intelligence that he approached Brigadier General Logan Feland, USMC, who was in overall command of Marine operations in Nicaragua, with the idea. The next day, BGen Feland, Maj Utley and Capt Edson sat down to discuss it.

“Major Utley tells me that you would like to go to Poteca. Can you get there from this coast?” BGen Feland began. No stranger to combat, Kentucky-born Logan Feland brought with him an impressive record as commander of the 5th Marines in France in World War I.

“Yes, sir; it can be done,” Edson replied.

A fighting man himself, BGen Feland needed nothing more in the way of an answer.

“Well, I’m going to give you the chance to do it.” BGen Feland went on to relate that aerial reconnaissance and human sources all confirmed evidence of Sandino’s forces in and around Poteca. Marines from the Northern District could not reach Poteca from the west soon enough to make a difference. If Sandino’s attempt to extend his territory into the Eastern District was to be stopped before it could start, it would be Edson who would have to do the stopping. In doing that stopping, Edson would need help, and he knew it.

Edson’s objective of Poteca could not be reached overland in time to do any good, not faced with the near impenetrable jungle that covered everything from the coast to the Highlands. For Edson’s Marines to hack and chop their way through the green wall of jungle that blanketed the entire area between Puerto Cabezas and Poteca would have consumed months. Only the Rio Coco existed as a realistic approach route to Poteca. In all of Nicaragua, only one group of people was capable of tackling the Rio Coco—the Miskito Indians.

From the very beginning, Edson had set about creating cordial relations with the Miskito, treating them with dignity and courtesy, always as equals, never as servants or menials. He knew that if he were to succeed in moving into the interior by way of the Rio Coco, it could be done only by gaining the trust of the Miskito. If the Miskito were to willingly join Edson’s force as boatmen, men accepted as equals, that trust would have to be earned through fair and honorable actions.

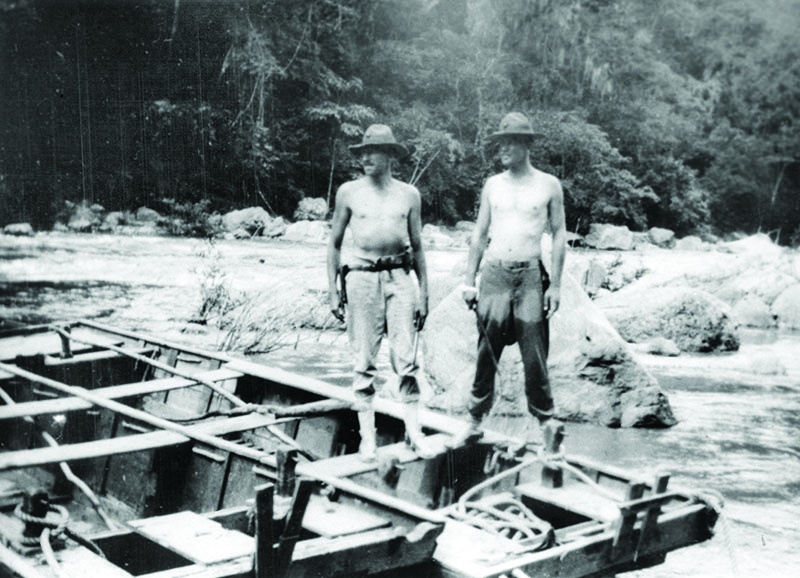

In his instructions to his Marines, Edson made it clear that fair and honorable actions must be sincere, not matters of convenience. “The Miskito are a proud people with a long history. Our success depends upon their assistance. They are far better at navigating this river than any of us. Only by dealing with them man-to-man, honestly, can we have any hope of succeeding. I expect each of you to conduct yourselves in such a fashion. l believe that if we offer the Miskito our hand in true friendship, they will accept it.” In a torrential downpour, Edson and 61 handpicked Marines started up the Rio Coco on July 26, 1928. Writing of it later to the girl he would one day marry, Private Edward Holston recorded: “It rains hard enough to knock you down. I’ve never seen anything like it. I haven’t been here very long, but if this is what life in Nicaragua is like, I’ll take Chillicothe [Ohio] any day.”

Fighting the Elements

Rain, constant and everlasting rain, day after day, was to be the trademark of the Rio Coco Patrol. The rain that fell for the entire period that Edson and his men made their way upriver was not of the gentle variety. Rather, it was a thunderous downpour that easily defeated any attempts to stay dry. For the Marines of the patrol, being soaking wet was an inescapable fact of daily life. All too soon that water-soaked existence would begin to exert an adverse effect on clothing, footwear and personal health as well.

Ferried along in pitpans (dugout canoes) by volunteer Miskito boatmen and guides, fighting the furious force of the river, Edson’s patrol advanced little more than 12 miles upriver that day. Wise to the ways of the river, the Miskito avoided any attempt to battle the river in midstream.

Out in the middle of that raging torrent, the force of the current was too overpoweringly strong to be overcome by simple muscle power. Full-grown trees of 60 to 100 feet in height, uprooted by the raging water of the Rio Coco, could be hurled downstream like toothpicks, carrying everything before them, obliterating anything in their path.

The experience of generations on the water had taught the Miskito that the prudent way to venture upstream against the Rio Coco in flood was to hug the riverbank where the current was considerably less strong. That did not mean that the job was easier. With the river out of its banks, the trees that grew to the water’s edge were now half in the water. The multitude of low-hanging limbs that normally were just overhead had become obstacles to be cleared.

While the Miskito provided the motive power with poles and paddles, Edson’s Marines provided the muscle power using axes and handsaws, cutting a path through the overhanging greenery. In addition to a shower of leaves, this activity also produced a shower of biting, stinging insects and occasionally a snake that had sought to escape the rising waters of the Rio Coco.

The relief system Edson had worked out to clear a path through the river improved their progress. While not easy, the undertaking was at least less daunting. As planned before departure, the lead pitpan tended to tree clearance for 30 minutes, then fell back to the tail of the flotilla, while the next pitpan in line assumed the lead role. Strenuous? Yes, extremely strenuous, but progress was being made. After a day of such exertions, all hands were more than ready for a night’s rest, which didn’t necessarily mean they would get it.

Each night camp was made ashore on such relatively dry land that could be found. Night also brought hordes of mosquitoes. The members of the patrol had been equipped with material that would make a crude shelter, as well as netting to keep the blood-thirsty mosquitoes at bay. Sometimes these field expedients were successful; most times they were not. Even if the netting succeeded in blocking out the mosquitoes, it failed to halt the nightly onslaught of sand fleas. Small enough to pass easily through the mosquito netting, the hundreds of biting sand fleas made sleep all but impossible, and life utterly miserable. Smudge fires were attempted once, but the coughing, nose-running, eyeburning results set most to enduring the hostile insects.

Insect life aside, the Rio Coco continued to be the Rio Coco. On the night of July 29, with the rain coming down harder than ever, Edson was forced to relocate his shelter to higher ground three times as the river rose 20 feet overnight. No one else did any better. All things considered; Edson felt that the wisest course of action for the following day was to give the day over to what rest could be had before battling the river again.

“Bandits”

That day brought the first evidence that Edson’s efforts to gain the trust of the Miskito were showing results. At mid-day, two Indians came into the patrol’s camp to report seeing what they described as four “bandits” less than 2 miles upstream on the north bank. There was a scarcely used trail that led to the location. If Edson wished, the Indians would lead his men there. Edson dispatched an eight-man combat patrol led by Corporal Elwyn Richards to investigate the area. Guided by the Indians, Cpl Richards’ small patrol caught the intruders completely by surprise. There was no resistance. Not a shot was fired. As soon as the intruders (undoubtedly Sandinistas) saw the Marines, they fled. The relatively small size of the Sandinista element, and their precipitate flight, led Edson to conclude that they were scouts on a reconnaissance mission who expected no resistance. Sandino now would be alerted to the presence of Edson’s force and its probable mission.

Could Sandino do anything about it? Not if Edson continued to have the trust and cooperation of the Miskito. As Edson moved deliberately but constantly upstream, the Indians of the widely scattered villages along the route proved to be ever more helpful, offering their services as advance scouts. On two more occasions, small groups of three or four “bandits” turned and fled upon encountering Edson’s rather unusual screening force. Sandino’s attempts to gain information of Edson’s force were turned back by the Indians who had accepted Edson as trustworthy. No shots were exchanged in these encounters.

The weather continued to be miserable and the river a monster, but thus far, Sandino’s every move had been pre-empted before Sandino could make it. The non-resistance of Sandino’s elements encountered and their small size both indicated that Sandino had in fact been caught flat-footed, with little manpower in an area he had considered safe from attack. The contest increasingly became a matter of which side could reach Poteca first, Edson or Sandino.

More than a week into the upstream fight with the Rio Coco, only the Marines of Cpl Richards’ small patrol had seen a Sandinista. The weather was something else entirely; all hands saw that all day every day. The combination of thunderous rainfall, soaring temperatures and suffocating humidity was not long in exacting a toll on both men and equipment. Even the most elementary forms of personal hygiene became monumental undertakings. Many completely abandoned any attempt at shaving. Edson himself soon sported a face full of bright red bristles that earned him a nickname that would last for the rest of his life: “Red Mike.”

As the month of July drew to a close, more than half of the members of the patrol were gulping quinine tablets twice daily to hold the effects of malaria at bay. Skin ulcers and fungus infections that turned armpits, groins and feet raw and painful were becoming increasingly prominent. The upstream fight against the Rio Coco was becoming less of a fight with Sandinistas and more a battle with the elements.

As fully as nature’s ravages affected the men, no less so did nature debilitate their equipment. Each morning revealed a thick coating of green mold on web equipment, footwear and leather. Clothing literally was disintegrating on men’s backs under the combined assaults of rain, heat and humidity. Very few members of the patrol were wearing socks; they had long since turned to grey pulp. On Aug. 3, Edson dispatched a trusted Indian guide to Puerto Cabezas with a message for Maj Utley requesting a complete resupply of clothing, shoes and “240 pairs of socks, woolen.” It was requested that as soon as the weather allowed, these materials be air dropped.

A break in the incessant rain on Aug. 5 brought a welcome relief from nature’s onslaught and an equally welcome resupply of clothing. At midday a pair of Fokker tri-motor transports from Managua delivered the clothing, shoes and socks Edson had requested. The beards remained, but the members of the patrol would no longer look like so many down-at-the-heels and out-at-the-seat ragamuffins.

Despite nature’s best attempts and the constant onslaught of biting, stinging insects, steady progress was being made. In the next three days, Indian scouts reported only one contact with “bandits” who fled without offering resistance. This sole confrontation with Sandinistas strengthened Edson’s growing confidence that the patrol had truly caught Sandino off guard with little in the line of combat power to contest Edson’s advance. The river and the jungle may have continued to be formidable opponents, but thus far Edson was winning every encounter with Sandino’s elements without having to fire a shot.

Contact with the Enemy

That would change on Aug. 7 when friendly Indians reported Sandinistas preparing an ambush site no more than 3 miles upstream. Unseen by the Sandinistas, the Indians carefully recorded their numbers at a total of no more than 20 men, equally distributed between each bank of the river.

As potentially dangerous as the situation was, there also was the danger to the Sandinistas themselves, who could have fired into each other. Also in Edson’s favor was the fact that the Sandinistas were unaware they had been detected. Edson was quick to see that the ambushers could well be ambushed themselves if he played his cards right. Merritt Edson set about doing just that.

Within minutes of being alerted to the danger ahead, Edson, with one platoon of 20 Marines and two Miskito scouts, surprised the Sandinista element on the north bank and in a brief but intense firefight, shot the Sandinistas to pieces. With Edson in the lead, the patrol charged headlong into the unsuspecting Sandinistas. Leaving four dead behind them, the Sandinistas fled. Edson then laid down a concentrated fire on the suspected site across the river. There was no return fire. There were no casualties among the Marines or Indians.

Three days later, the Marines cautiously entered Poteca. They were not opposed. Villagers reported to Edson that an estimated 15 “bandits” had left two days before. Sandino’s attempt to carry the conflict into the Eastern District had been stopped before it could start. Sandino’s plan to disrupt the elections was stillborn. By doing the unexpected, doing what “couldn’t be done” and confronting Sandino with a situation for which he was unable to respond, Edson had completely altered conditions in Nicaragua. With no outside interference, the election of 1928 was conducted without incident. Liberal Jose Maria Moncada was elected president in balloting that both sides agreed had been fairly conducted.

For his leadership and determination throughout the entire period of the Rio Coco Patrol and for his complete disregard for his personal safety during the engagement of Aug. 7, 1928, Merritt Edson received the Navy Cross. In August 1942, he received a second award of the Navy Cross for his courageous leadership of the 1st Raider Battalion during the seizure of Tulagi Island in the opening stages of the campaign for Guadalcanal. Later, on Guadalcanal itself, Merritt Edson received the Medal of Honor for his defense of “Edson’s Ridge,” which safeguarded the all-important Henderson Field.

The Rio Coco Patrol, as little-known as it is today, serves as a classic example of the principle of surprise. By doing exactly what Sandino least expected, from the direction Sandino had not expected at all, Merritt Edson, with 61 Marines and one U.S. Navy pharmacist mate, completely altered events in Nicaragua in the important year of 1928.

Forty years later, in another war on the other side of the world, Edson’s manner of establishing an association of trust and respect with the Miskito would serve as a foundation block for the Marine Corps’ successful Civic Action Program in Vietnam. In Nicaragua in 1928, Edson knew that you could not expect a man to stand beside you if you treated him as an inferior.