LAI: Light Armored Cavalry

Posted on August 07,2019Article Date Oct 01, 1989

by Capt Philip D. deCamp, USA

Winner of the 1989 Marine Corps Gazette Professional Writing Award for AWS Students

As the Marine Corps moves to refine its LAI concept and enhance its capability for independent mobility operation, it should turn to the lessons learned by the Army’s armored cavalry.

Although light armored infantry (LAI) battalions have been fielded and operational for sometime, LAI doctrine and employment continue to be debated. In the LAI concept, the Marine Corps has recognized the need for independent mobility operations in support of Marine tactical maneuver. This concept is well proven through history, and the Army’s armored cavalry has performed this role since World War II. As the Marine Corps refines its LAI concept, it should turn to lessons learned by the armored cavalry-the “masters of mobility”-as it refines the LAI organizational structure and operational concepts.

First, consider the relationship between the missions of the two units. Although the cavalry is capable of many missions, its contribution is best summed up in the following statement taken from a paper written a decade ago at the Armor Center at Fort Knox:

Cavalry fulfills three basic and closely related functions: reconnaissance, security, and economy of force. These traditional functions are inherent to warfare. They are valid on today’s battlefield and will still be valid on tomorrow’s. Some force must fulfill them, and the force that does so is cavalry, whether called so or not.

The LAI battalion, although not called cavalry, was specifically assigned these “inherent” cavalry functions in a recent change to OH 6-6:

The LAI battalion will conduct reconnaissance and security operations and economy of force missions in support of the Marine division or its subordinate elements, and within its capabilities the battalion can be employed in offensive or delaying actions that take advantage of its speed, mobility, and firepower.

How will the LAI battalion perform this cavalry role for the Marine division? Will it replace traditional Marine reconnaissance teams, deploying its own secret units deep behind enemy lines to report enemy preparations and movement? No! As a cavalry unit, the LAI will not only watch the enemy, it will engage him. In fighting for information, the LAI will make the enemy commander show his hand, either by sustaining the fight, committing reserves, breaking contact, or even by inaction. The LAI will obtain current battlefield information concerning enemy intent, giving the Marine operational commander the speed and flexibility necessary to operate within the enemy’s decision cycle. The chief of Armor’s Cavalry Branch explained this contribution to maneuver warfare in an article in Armor magazine (JanFeb86) as follows:

Cavalry [the LAI], by providing current combat information, facilitates a commander’s ability to seize and sustain the initiative and concentrate overwhelming combat power against the enemy at the decisive place and time.

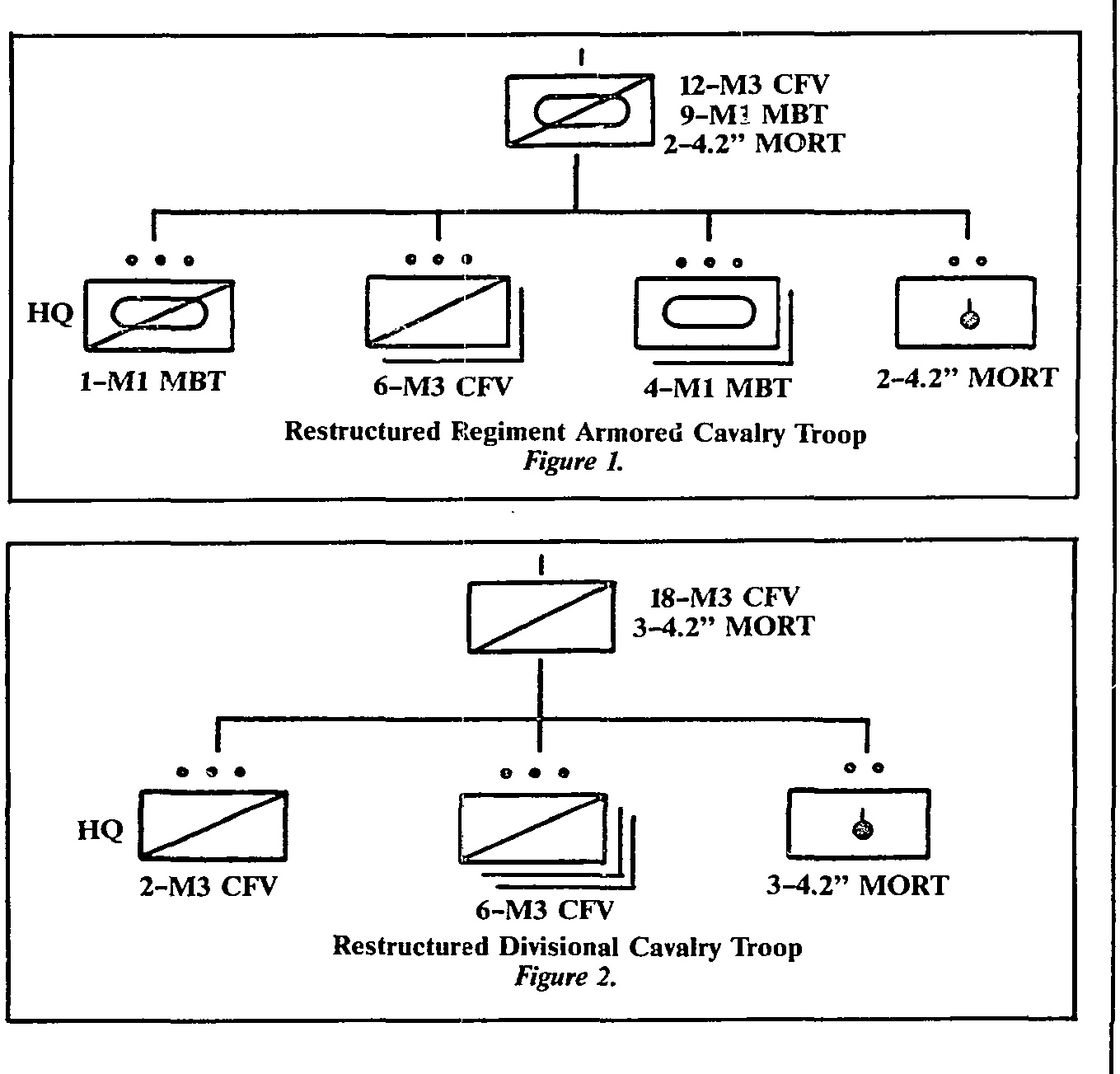

To accomplish this mission on the mechanized battlefield, cavalry commanders, after dealing with constant attachments and detachments during World War II, were convinced that a cavalry unit needed to be a self-contained, combined arms organization. The cavalry platoon of the mid-1960s typified this concept by merging scouts, tanks, infantry, and mortars into a platoon-sized combined arms team. At the company level, an organic CSS structure gave the cavalry troop the capability to sustain itself independently. This organizational approach served well but standardization and endstrength eventually forced restructuring as show in Figures 1 and 2.

The new structure created separate scout and tank platoons, deleted organic infantry support, and emphasized only parts of the cavalry mission rather than the combined arms team. Furthermore, it required the division commander to augment the lighter divisional cavalry only as the mission required, adding units unfamiliar with cavalry operations into the complex cavalry scenario. The lessons learned by the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment (3d ACR) at the National Training Center (NTC) indicate that this structure does not support the cavalry mission. Cavalry requires a fixed structure very similar to the earlier organization. Col Jarrett R. Robertson, commander of the 3d ACR, questions the task organization approach of giving organic cavalry units only a temporary capability to accomplish traditional cavalry roles:

The book says that if a [cavalry] unit requires such a capability, the division can beef up the squadron with maneuver companies. This solution will not work We learned that during WWII. That’s why we organized the type of cavalry units that we had in the 50s and 60s. The ability to blend scouts and tanks into an effective fighting force is a major training challenge. [Emphasis added.)

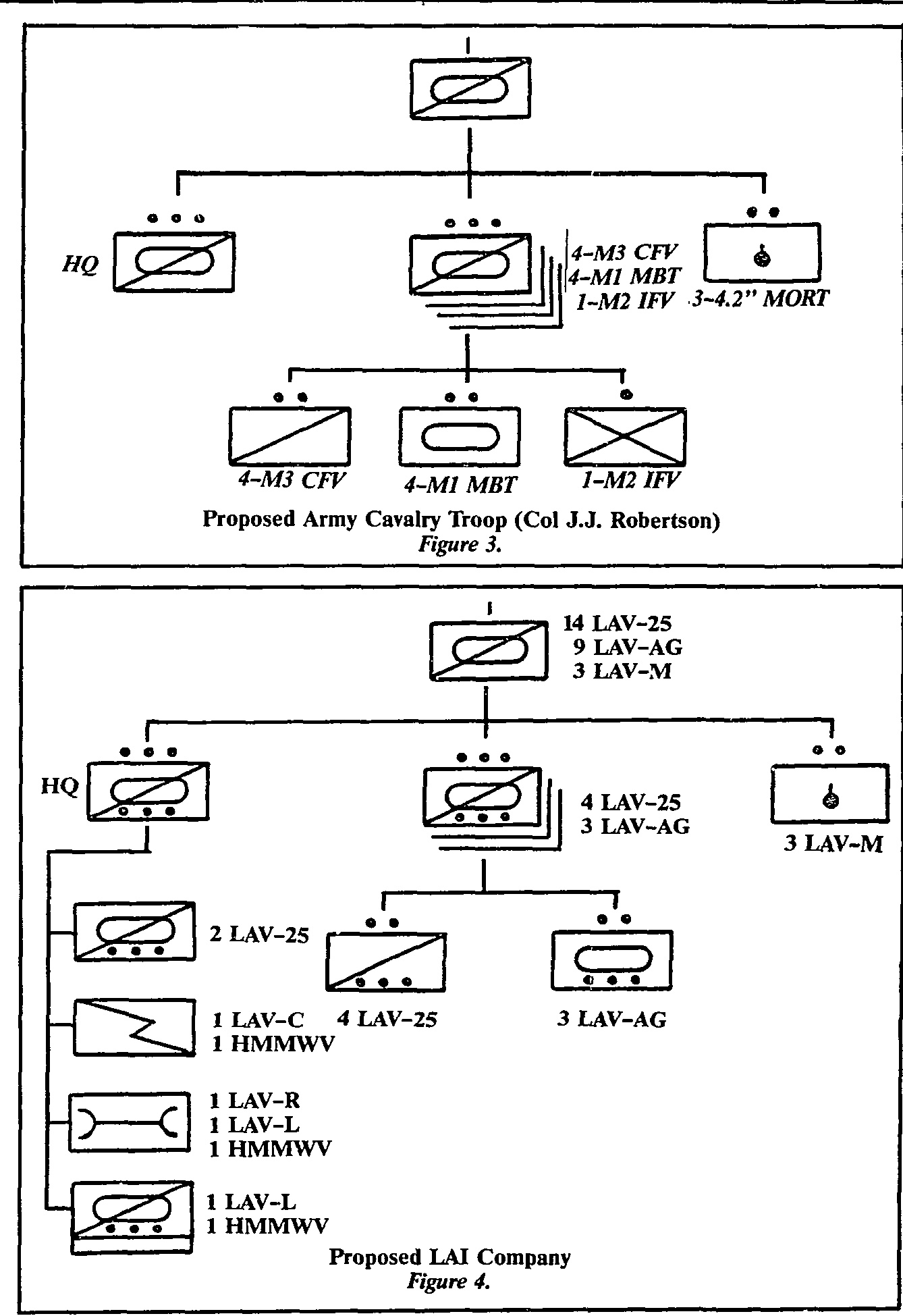

After his experience at the NTC, Col Robertson proposed the cavalry troop organization shown in Figure 3. Supported by the majority of armored cavalrymen, this structure once again integrates scouts, tankers, and infantrymen at platoon level and provides a substantial organic logistical package at troop level.

The Marine Corps’ LAI community can learn from the cavalry’s organizational mistakes. A combined arms LAI company similar to Col Robertson’s proposal is outlined in Figure 4. This self-contained LAI company, capable of operating independently and sustaining itself for some time, would give the Marine division the cavalry asset essential to maneuver warfare.

At platoon level, this proposal relates the LAI assault gun section to the cavalry tank section, since the roles of the two weapons are much the same in cavalry operations. The assault gun obviously is not a tank and is not designed to perform all tank missions. But, in its primary scout support role, the assault gun will perform the same mission the cavalry tank performs for Army scouts. The tank, with its high velocity main gun, provides instant fire support, enabling forward scouts to quickly disengage-a capability the TOW can’t provide. The assault gun, as a complement to the TOW-equipped antitank variant of the LAV, the LAVAT, will likewise support Marine scouts.

A similar relation consolidates scouts and assault gunners at platoon level. The cavalry platoon, before the recent reorganization, proved the advantages of blending separate specialties into a cohesive fighting team. As scouts, tankers, and infantrymen trained to fight together at the platoon level, intense cohesion developed. The supporting overwatch teams were dedicated to helping comrades in the forward areas, not only because of mission but because of personal commitment Thoroughly tested platoon standing operating procedures were well known and understood, and training exercises at every level practiced the combined arms concept Additionally, by bunking, eating, and socializing together, soldiers informally learned the missions and abilities of all parts of the combined arms team. It became second nature to predict actions of other elements when individual personalities became well known. Soldiers, motivated and encouraged to learn each other’s job, made duty interchangeability easy and effective, an advantage that enabled units to reorganize rapidly after high-casualty engagements and immediately continue the mission.

Will the new structure provide these advantages by training soldiers in the combined arms concept at every level? The new cavalry experience indicates not. The S-3 of the 3d ACR explains the difficulty of scout-tank coordination at the NTC:

The M1A1 proved essential to scout survivability. All too often, when the regiment mistakenly decoupled tanks and scouts, the scouts died swiftly…. 3d ACR scouts performing recon and security functions had limited survivability unless they operated with their associated tanks. The difficulty of maintaining this formation argues against the flippant response that tanks can be task organized into a cavalry structure when needed. Despite great effort, it was a continuous challenge to maintain effective tank/ scout coordination. [Emphasis added.]

By replacing “tank” with “assault gun” this statement will apply to the LAI cavalry team as well. Because of the complex nature of cavalry operations, all parts of the combined arms team must be well versed in fighting together. A fixed platoon task organization, in which the team always lives and fights together, is essential.

The only major difference between the Army and Marine platoon organizations is the infantry squad; the Marine platoon doesn’t get one. The Army’s M3 cavalry fighting vehicle (CFV) only dismounts two scouts, far too few to provide adequate dismounted security, thus the addition. The LAV-25 dismounts four, thus 16 LAI scouts are available to provide the dismounted support Furthermore, adding a separate infantry squad to the LAI platoon could require adding two LAV-25S or developing even another LAV variant, an LAV armored personnel carrier (LAV-APC). Although more infantry might well be useful, adding them is impractical at best.

To sustain these combined arms platoons, this proposal creates a large headquarters platoon, with the company executive officer (XO) as platoon commander. The heart of the platoon is the company headquarters section. Located in two LAV-25s it can move forward as necessary to fight the battle. The company commander and his fire support representatives man one LAV-25 while the second provides wingman support. In a change from the current organization, the company XO is not in this section. He heads up a new section created by the transfer of an LAV-C communications vehicle from the current battalion communications platoon.

This new LAV-C is the nucleus of a new communications section created to enhance one of the most important weapons of a scout-his radio. Since cavalry operations are by nature reporting operations, the Army cavalry has learned that information processing is vital to mission accomplishment. The XO, as the combat reporter, will remain in the LAV-C running the company’s tactical operations center (TOC). From the TOC he monitors the battle, submits reports, issues instructions, and acts as the company fire support coodinator, thus freeing the commander to fight the battle. An added communication chief and two radio repairmen provide the vital communications links. An armored high mobility, multipurpose wheeled vehicle (HMMWV) trails the LAV-C to provide two capabilities. First, it functions as a mobile communications contact vehicle to make quick repairs or exchange equipment as necessary. Second, it provides mobility for the XO enabling him to move to the front and take over the battle from one of the LAV-25s without endangering the LAV-C.

The modern equipment found in the LAI company requires detailed first- and second-echelon maintenance. In addition to operational and preventive maintenance, battle damage from swift and lethal engagements necessitates a large “on-the-spot” maintenance, recovery, and extraction capability at the unit level. A strong maintenance section, equipped with both a recovery LAV and a logistics LAV, is another vital asset These vehicles make heavy deliveries to stranded vehicles and support repair/recovery operations as needed. An armored HMMWV, acting as a maintenance contact team, checks battle damage and establishes priority of recovery and repair assignments.

As the LAI company fights for information, it will expend enormous amounts of supplies-especially classes III, IV, V, and IX. Extended movements, quickly changing missions, and engagements against numerically superior forces are only a few reasons for this heavy reliance on logistics. An organic company supply section, reporting directly to the LAI company commander, can tailor its support to the demands of the specific LAV mission. In the proposed organization, an LAVL logistics variant provides heavy supply transport while a HMMWV, probably manned by the company gunnery sergeant, allows for rapid coordination and delivery of smaller supplies.

A final addition to the LAI company brings the battalion mortars down to company level. A three-tube mortar section, firing from three mortar variants (LAV-Ms), will provide the LAI company the flexible and responsive indirect fire vital to security and reconnaissance operations. The Army cavalry community, embracing the independent combined arms team concept, has long recognized the necessity for substantial indirect fire at troop level. The requirement for responsive and specialized indirect fire in cavalry operations is so great that the Army cavalry squadron has an organic 155mm howitzer battery assigned as well. Although the Marine division artillery can’t be expected to likewise attach a battery to the LAI battalion, a company mortar section, operating in conjunction with direct support artillery, will give the LAI company the indirect fire support essential to independent operational maneuver.

The Marine Corps’ maneuver warfare concept places a premium on mobility and flexibility. As a descendant of the Horse Marines, the “Light Armored Cavalry” proposed here would have the inherent mobility to shift quickly to diverse roles anywhere on the battlefield. But like all historical cavalry units, a fixed combined arms LAI structure at company level is essential to achieving independent flexibility. The Marine Corps and the Army share many elements-infantry, armor, artillery, and aviation, to name a few. It’s time we share another element essential to land warfare, the cavalry, and use historical cavalry lessons to develop our current doctrine and organization. US MC