Dual Identities: Marines and Firefighters Embrace Their Call to Service

By: Kyle WattsPosted on November 15, 2024

The American fire service and Marine Corps maintain a long-standing relationship, enjoyed and perpetuated by veterans of both services. Though dramatically different at face value, one seeking to close with and destroy the enemy while the other seeks to save life and protect property, the identities harmonize within the men and women who have worn both uniforms. Thousands of Marine veterans today have discovered this gem in the civilian world, offering a lifestyle with stunning similarity to service on active duty. Indeed, veterans from every branch find fulfillment, community, and a natural career fit within the fire service.

A select group possesses the rare opportunity to hold both careers simultaneously, serving as Marine Corps Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) Specialists. Out of more than 170,000 personnel on active duty, less than 800 of these firefighters exist within Marine Wing Support Squadrons (MWSS), or as permanent staff of the Marine Corps Air Stations (MCAS). To achieve their 7051 Military Occupational Specialty (MOS), ARFF Marines begin their training with the U.S. Air Force.

The Department of Defense (DOD) Fire Academy trains firefighters from the U.S. Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, and even a few from the Navy, at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas. After three months, students graduate with basic certifications in structural firefighting, aircraft rescue and firefighting, hazardous materials operations, and Emergency Medical Responder. From the schoolhouse, ARFF Marines move on to their respective duty stations, either “wing side” or “station side.”

“Station side” firefighters staff MCAS fire departments around the world. They work in a non-deployable capacity, operating in similar fashion to typical stateside firehouses. Crews remain on shift for 24 to 72 hours at a time. During their tour of duty, Marines work together, train together, cook, clean, and exercise together. Their primary mission is responding to any sort of aircraft-related emergency, thus enabling the flying squadrons of each air station to maintain flight schedules 24/7.

The primary apparatus utilized for aircraft firefighting is the P-19R. These behemoth trucks have served the Marine Corps in various configurations since the early days of the Global War on Terror. In addition to fire hose, ladders, and compartment space for tools and firefighting equipment, a P-19 hauls 1,000 gallons of water, 130 gallons of foam, and 500 pounds of Halotron, an auxiliary firefighting agent. Dual turrets mounted to the roof and front bumper dispense up to 750 gallons of water per minute. Without hydrants around a flight line, station fire departments also utilize water tankers, hauling up to 4,000 gallons.

ARFF Marines serve as subject matter experts on aircraft and vehicle extrication. With axes and Halligan bars, or hydraulic spreaders, cutters, and rams, firefighters train to extricate patients from vehicles or different types of aircraft. The Marines’ training as Emergency Medical Responders works closely in conjunction with their extrication skill set, as incidents in any form often involve patients needing immediate medical care.

Station fire departments work in conjunction with the local departments surrounding their base. Even in places like Japan, where a language barrier poses a significant obstacle to overcome, Marines train with their Japanese counterparts to understand each other’s tactics and capabilities and develop plans for mutual aid in the event of significant incidents.

This past summer, the ARFF Marines from MCAS Iwakuni, Japan, were recognized for their outstanding performance, earning top scores as the 2023 USMC Medium Fire Department of the Year. The award marked the second year in a row these Marines earned the title for their department size category, and no small achievement. They displayed an outstanding example of performance and professionalism, while maintaining standards of excellence in both their qualifications as airport firefighters and those required of every Marine, such as weapons qualifications and the physical fitness test.

One Marine from the Iwakuni ARFF department stood out even further. In June, Sergeant Yasmine Huley-Morris received the 2023 Military Firefighter of the Year Award. This immense individual honor was awarded by the DOD following a competitive selection process. Nominees included not only firefighters from the Marine Corps’ comparatively small pool, but servicemembers across every branch of the U.S. military. Huley-Morris serves as a station captain, responsible for 22 Marines and four pieces of firefighting or rescue apparatus. During her tenure with at Iwakuni, Huley-Morris has responded to numerous incidents, including Nov. 29, 2023, when a U.S. Air Force CV-22B Osprey lifted off from MCAS Iwakuni and crashed in the water off the Japanese coast, killing eight airmen.

On the flip side of the same coin, “wing” firefighters with the MWSS lead a significantly different lifestyle. While the number of personnel assigned to station fire departments varies depending on the size of the airfield and the type of aircraft it supports, the Table of Organization for a MWSS calls for 43 firefighters. These Marines hold the same certifications and utilize most of the same equipment but work in forward deployed aviation ground support elements. Their capabilities include supporting operations such as Forward Arming and Refueling Points (FARPs), Aircraft Salvage and Recovery, Base Recovery After Attack, and casualty evacuations.

“The biggest difference between MWSS and station firefighters is the simple fact of deployable versus non-deployable,” said Gunnery Sergeant John Ritchie, who currently serves as the ARFF Assistant Chief of Operations, Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, MCAS Yuma, Ariz. “In my opinion, you cannot learn the trade of a 7051 without spending time in both types of units.”

On Aug. 22, Ritchie was honored as the 2024 Expeditionary Warfare Noncommissioned Officer of the Year for his recent role on deployment with the 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU). Beginning in November 2022, Ritchie served as the Marine Wing Support Detachment Operations Chief. In addition, he was the senior firefighter on the deployment.

A typical MEU deploys with only four or five firefighters. The 13th MEU set sail with a larger detachment, including nine ARFF Marines split across two ships. Their primary focus centered around FARP operations, enabling more than 500 flight hours in over 200 sorties from multiple FARPs throughout the deployment. To support firefighting operations, the MEU embarked the Marine Corps’ HMMWV-mounted Fire Suppression System (FSS) rather than the bigger and heavier P-19. Though significantly limited in firefighting capabilities when compared to the P-19, the FSS offers a lightweight, off-road-capable platform. The Marines executed the deployment free of aircraft mishaps and returned home in June 2023. The most memorable call for service during their time abroad came in Thailand when the firefighters helped extinguish a wildfire lit off during a live-fire training range.

Early in Ritchie’s career in 2009, he deployed to Afghanistan. His ARFF platoon from MWSS-372 served aboard Camp Dwyer and Camp Bastion during the deployment.

“One of the first emergencies we had in country was a Huey and a Cobra that collided in midair and crashed outside the wire,” Ritchie remembered. “We were tasked to respond, so we met up with a quick reaction force in our P-19s and went out to do what we had to do.”

Other calls for service ranged from minor fires to forklifts rolled over. Much of the firefighters’ time was dedicated to medevac missions, helping move casualties of every nationality, friendly and enemy, from helicopters to ambulances for transport to the hospital.

Shortly after Ritchie’s squadron returned home, Marines from MWSS-274 battled a massive inferno at Camp Leatherneck, the Marine Corps base adjoining Camp Bastion. In May 2010, the Supply Management Unit lot, packed full of every sort of supply, somehow lit off. By the time ARFF arrived, heavy equipment operators were plowing fire lines through boxes and pallets with bulldozers working to stem the fire spread. The blaze increased dramatically as the sun set. A massive sandstorm descended as the firefighters dragged hose through the burning lot. Visibility decreased less than 6 feet. The winds fed the fire as it consumed everything in its path. Even the air seemed on fire, glowing hot hues of orange and red. The firefighters and equipment operators battled the blaze undeterred, salvaging everything they could. By morning, the inferno was finally under control.

Two years later, ARFF Marines fought fire while under fire during one of the most catastrophic attacks to occur through the entire 20-year war in Afghanistan. Shortly after 10 p.m. on Sept. 14, 2012, Sgt Justin Starleigh was in the MWSS-273 office on Camp Leatherneck when a Marine walked in and began putting on body armor. When Starleigh asked what he was doing, the Marine told him the British-controlled airfield at Camp Bastion was under attack.

2012 insurgent attack on Camp Bastion, Afghanistan flightline.

“I called the team stationed over at the airfield and the sergeant we had over there was irate,” remembered Starleigh. “I asked what was going on and he was like, ‘there’s Taliban everywhere, there’s fire, we’re under attack!’ I realized this was not a drill and told him we were on the way.”

Starleigh and two other sergeants loaded their firefighting gear, combat gear, and a backpack full of rifle magazines into a P-19 and headed toward the flight line. They paused at the runway, awaiting clearance from the Brits to cross over. In the distance, an orange glow illuminated the night sky.

Unknown to them, 15 enemy fighters had penetrated the base perimeter. One team of insurgents killed two Marines and went to work destroying aircraft lined up near the runway. Another team attacked the flight line’s cryogenics facility. At the other end of the runway, massive bladders storing hundreds of thousands of gallons of aviation gas lay in a designated fuel farm. A third insurgent team fired Rocket Propelled Grenades into the farm, igniting a raging fuel fire.

Starleigh’s P-19 finally arrived on scene. Marines in another truck geared up for primary fire attack and nosed up to the berm surrounding the fuel farm. Intense heat radiated from the fire as the aviation fuel burned at temperatures over 1,000 degrees. A firefighter standing in the roof hatch aimed the turret toward the blaze and opened the nozzle. Starleigh positioned his P-19 behind the primary truck to provide additional water. Enemy rounds cracked through the air. The Marines not actively engaged in firefighting fanned out around the trucks, lying prone behind their rifles.

A Marine assigned to the fuel farm approached Starleigh and reported they had potential casualties missing. He pointed away toward a nearby hangar where they had last been seen. Starleigh and another ARFF Marine formed a fire team with two fuel specialists and set out to the hangar. They cleared the inside of the structure then went outside. Large shipping boxes and storage containers funneled them into a corridor down the side of the hangar. Pallets of water and other supplies littered the area, offering concealment throughout the alley.

Starleigh moved on point through the darkened maze as the Marines approached the back corner of the hangar.

“We got about 15 feet from the end of the building when an insurgent stands up from behind a Palcon at the end of the road and started shooting,” Starleigh said. “I immediately returned fire and the figure fell down. In my brain, I don’t know if I hit him or if he just went down to take cover. I don’t know what he’s hiding behind, and I don’t know who else might be behind him. I just knew we needed to get out of that corridor.”

Starleigh fired a magazine to cover the Marines as they withdrew toward the P-19s, still fighting the fuel fire nearby in their direct line of site.

“There was a lot going on,” he remembered. “Our ARFF leadership arrived and was looking for accountability. We were in contact right there at the hangar. We were fighting the fire and establishing 360 security. Rounds were flying. One Marine was providing aid to a British soldier who got shot. All the while, Harriers were getting blown up on the other side of the airfield, the Marines over there were engaged, and there was another fire going at the cryogenics lab.”

When the attack began, Corporal Vincent Colombo and three other firefighters from MWSS-373 drove their P-19 toward the aircraft along the runway. Multiple AV-8B Harriers had lit off, igniting the fabric sunshades covering them. Smaller spot fires burned throughout the vicinity. The firefighters stretched hose lines and extinguished each aircraft one by one as gunfire echoed around the structures. A quick reaction force, filled out by a hodgepodge of mechanics, support personnel, and even British firefighters, dispersed through the area repelling insurgents while the Marines fought the fire.

“I have always joked with people, we are like the ultimate POGs,” Colombo said today. “We are not meant to close with and destroy the enemy. We are meant to save lives and protect property. We were in such a unique position. It’s not like we were wearing flak and Kevlar underneath our firefighting gear. We couldn’t carry our rifles because we were carrying hundreds of feet of hose to put out the fires.”

With the Harrier fires extinguished, Colombo’s team moved to the cryogenics facility, an interconnected group of shipping containers modified to house the lab where liquid oxygen was stored for the jets’ on-board oxygen systems. A single door led into the facility. The limited ventilation contained all the heat and smoke inside, making conditions untenable even for firefighters in full gear. The Marines advanced a hose line and began flowing water while pulling items outside to create space. Thick black smoke pulsed through the open door, rolling upwards like an inverse waterfall. Heat baked the Marines through their gear. The opening fed the fire with the oxygen boost it needed to flashover. Everything inside that could burn, including the impenetrable smoke banking down from the ceiling, simultaneously ignited in an explosion of fire.

Mercifully, the Marines remained unharmed as they backed out the door. They lugged a saw to the back side of the containers and cut a large hole, creating a flow path through which the smoke and heat could escape. Running low on air, the Marines swapped bottles in their self-contained breathing apparatus and went back to work.

Under normal circumstances, multiple trucks with numerous firefighters would be on scene to accomplish every task and rotate fresh crews into the structure. They also would not be getting shot at. The ARFF Marines at the cryogenics facility fought alone for nearly two hours to control the blaze, enduring everything the fire and the enemy could throw at them.

British ARFF personnel brought tankers to the fuel farm, providing many thousands of gallons of water needed to knock down the fire. Apache attack helicopters circled overhead, hunting down any insurgents remaining inside the wire. After four hours the attack ended, but ARFF Marines continued extinguishing spot fires all night. Two British firefighters suffered gunshot wounds while battling the fuel farm blaze. In total, the fire consumed 119,000 gallons of fuel. The insurgents destroyed eight Marine Corps Harriers and a U.S. Air Force C-130, and damaged other aircraft or equipment to varying degrees. Two Marines died and a total of 17 U.S. and British personnel were wounded.

When the sun rose, multiple enemy bodies lay around the vicinity where Colombo and his team fought the Harrier and container fires. They were recognized later in press releases and after actions for their role containing the hanger fires and saving millions of dollars worth of equipment, but received no personal awards or Combat Action Ribbons. Starleigh learned the insurgent his team encountered by the hangar was dead, cut down by his covering fire.

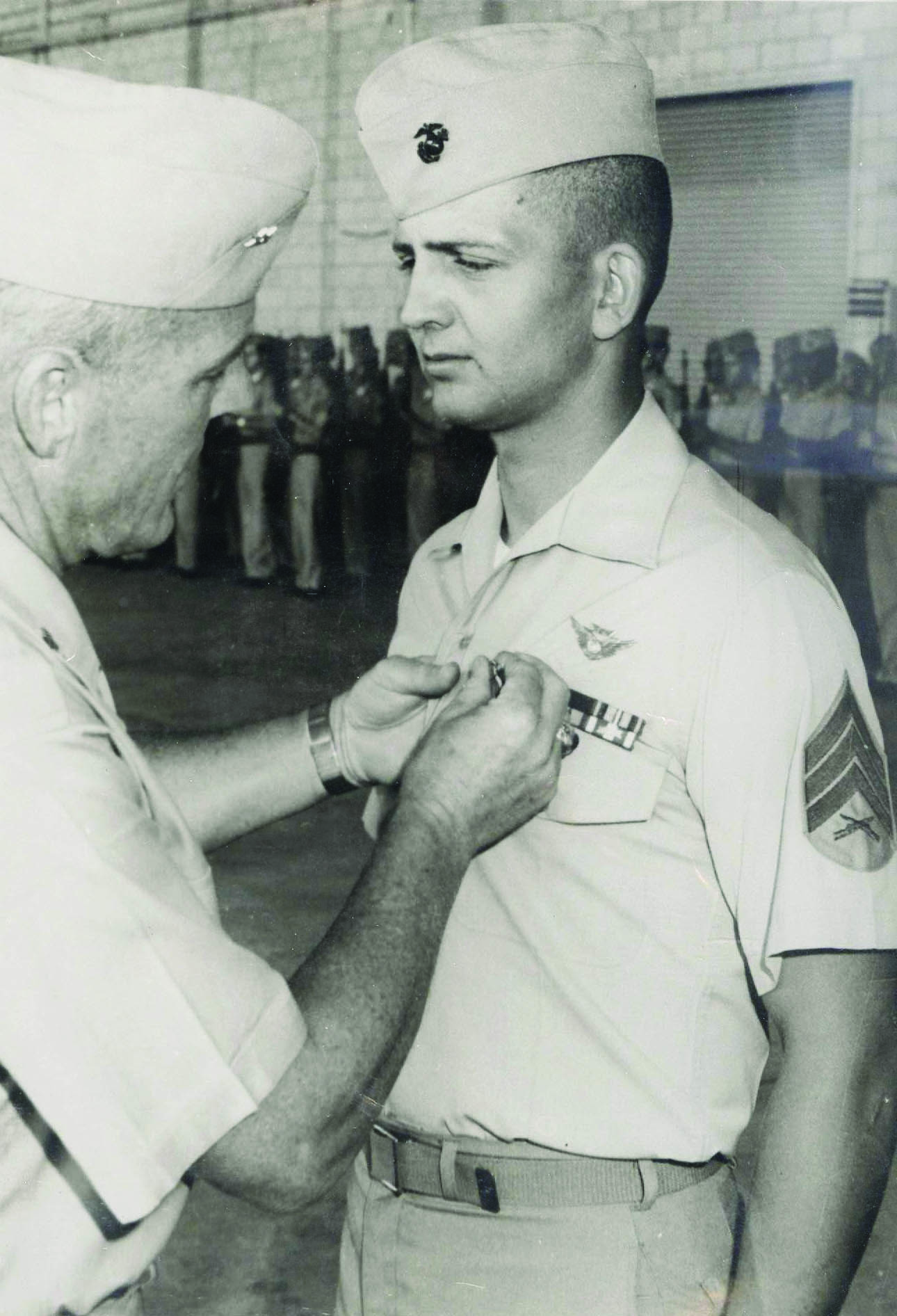

For his actions and initiative leading the ad hoc fire team in search of the casualties, Starleigh received a Combat Action Ribbon and the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal with Combat Distinguished Device.

Starleigh reenlisted and moved onto the drill field immediately after leaving Afghanistan. He is now a master sergeant serving with MWSS-273 out of Beaufort, S.C. At his present rank, Starleigh holds one of the most senior roles within his MOS where Marines are still certified as firefighters and actively involved in the daily operations of their respective fire departments.

Beyond master sergeant, career Marine firefighters have two available paths. Fewer than 10 hold the rank of master gunnery sergeant, serving in Corps-wide planning or training roles. Considerably more progress into warrant officer ranks as a 7002, Expeditionary Airfield and Emergency Services Officer. Colombo serves in this capacity today, now a chief warrant officer 3 serving with Marine Air Control Group 38. These senior Marines serve at each MWSS, air station, Wing, and Marine Expeditionary Force. They hold primary responsibility for planning and overseeing the installation, operation, and maintenance of expeditionary airfield equipment and aircraft recovery equipment. They can serve as Incident Commander during aircraft emergencies, structure fires, rescue operations, and hazardous materials responses.

Despite the available career paths, some ARFF Marines choose to leave the Marine Corps following their first enlistment. Marine firefighters have the opportunity to leave active duty with directly transferrable skills, performing the exact same job in the civilian world. The decision, in the end, boils down to which uniform, which identity, each individual wants to wear.

“In my opinion, you have to love being a Marine more than you love being a firefighter,” said GySgt Ritchie. “The guys who love being a firefighter more than anything else in the world are probably better suited to serve with a civilian or federal fire department. I think you have to love the ability to be forward deployed. You have to wake up every morning, put the uniform on, look in the mirror, and still have a lot of pride wearing that eagle, globe, and anchor.”

For those who move on, the civilian fire service offers a familiar and promising career. ARFF Marines may find the shift more seamless, but Marines coming from any field will discover in the firehouse a world full of people and experiences that likely checks all the same boxes that earlier convinced them to join the military.

Todd Angell left the military in 2012 after serving as a U.S. Navy corpsman with 1st Battalion, 8th Marines. The citation for his Silver Star details a three-month period during 2010 in Afghanistan where Angell single-handedly rescued multiple Marines or Afghan soldiers who were blown up by improvised explosive devises, grievously wounded, and trapped inside a minefield. It later describes his critical role in gunfights, personally accounting for multiple enemy dead. Today, Angell serves as a firefighter with Hillsborough County, Fla., and as a flight paramedic flying out of a hospital in Tampa.

“Being a Fleet Marine Force corpsman was a dream of mine,” he said. “I’m super proud of it and it is something that’s always going to be a part of me. But that was a goal I accomplished in another life, and goals change. Not everyone wants the military to be their identity forever, but even if you just serve four years and get out, hanging up that uniform is one of the hardest things you’ll do.”

Similar to transitioning ARFF Marines, as a Navy corpsman, Angell’s path into the fire service might appear natural or inevitable, moving from one “first responder” role into another.

“I’ve talked to several younger guys who are still active duty, and I tell them don’t look at this job like it’s the only thing you can do when you get out. It’s a great job. It’s definitely not for everybody, but those of us who are in it love it. I couldn’t see myself doing anything else. I think a lot of guys coming from the military would fit that mold.”

In 2014, the FDNY Marine Corps Association erected a monument at the National Museum of the Marine Corps to honor the New York City firefighters who died in the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. A total of 343 FDNY firefighters died that day. Of those, 17 were United States Marines. (Kyle Watts)

The baseline values and life lessons Angell gained from the military set him up for success. Simple things learned as early on as boot camp prove especially applicable in the fire service; showing up on time, pride in your appearance, and the humility to shut up and listen when someone is trying to teach you something, even if you think you already know the answer. Perhaps most important is the understanding that the fire service, like the military, should be approached as a noble calling, not for everyone and not just the next job.

“We served our nation, and now to be able to serve our communities is a natural fit for us,” said Dakota Meyer, Marine veteran who is now a firefighter. “We all served in the military because we wanted to be needed, to be part of the greater good, and to do something that not everybody had the opportunity to do. The fire service fills that same cup; being able to be whatever it takes to make the world that you’re a part of just a little bit better.”

Meyer left active duty in 2010 after seeing combat in Iraq and Afghanistan and becoming the first living Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War. Ten years later, in 2020, Meyer enrolled in the fire academy in his home state of Texas and joined the volunteer firefighters serving with Spicewood Fire Rescue in Burnet County.

On Feb. 22, 2022, Meyer and two other volunteer firefighters responded to a reported vehicle in water. Once on scene, Meyer spotted a pickup truck that ran off the road, through a fence, and was now completely submerged in a pond just below the surface of the water. A civilian on the bank told him a victim remained trapped in the truck. Meyer stripped off his heavy bunker gear and jumped in. He swam to the truck and searched for a way inside, treading in the frigid water for several minutes before another firefighter successfully broke out a window. Meyer dove down into the cab, located the unconscious victim, and helped drag him back to shore. The firefighters performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation until paramedics arrived in a helicopter to rush the victim to the hospital. By the time the helicopter landed, the victim’s pulse returned, and he started breathing on his own. Miraculously, four weeks later, he walked out of the hospital fully recovered. For their swift actions and lifesaving measures critical to the patient’s outcome, Meyer and the other firefighters involved in the rescue received the department’s Firefighter Medal of Valor.

“The level of creativity being in this job is kind of like being a Marine,” Meyer said. “Every gunfight is different. Being a warfighter requires a level of creativity, taking everything that you have, your skills and capabilities, and putting those things together in a way to provide a solution to the problem that you face. That’s exactly what being a firefighter is. You’ve got what you’ve got and how are you going to fix the problem that’s at hand?”

Today, Meyer serves as a Fire Captain with Spicewood, as well as serving part-

time with another professional department in Burnet County. He is one of many Marines who have found and embraced this new uniform and identity, continuing the long-standing relationship between Marines and the fire service.

Another example from years past is Gunny Sergeant Fred Stockham . Stockham was a firefighter in Detroit, Mich., before enlisting in the Marines in 1903. When his four-year contract ended, Stockham returned to the fire service in Newark, N.J., where he remained until reenlisting once again in 1912. By 1918, Stockham achieved the rank of gunnery sergeant while serving in the trenches during World War I. On the night of June 13 to 14, Stockham’s company endured heavy German bombardment with high explosives and mustard gas. Stockham donned his gas mask as the yellow-brown chemical seeped across the front spilling into the trenches. A Marine next to Stockham lay wounded in the mud, his gas mask shot off his face. Without hesitation, Stockham removed his own mask and placed it on the wounded Marine. Mustard gas seared his lungs and blistered his skin as Stockham evacuated the casualty to safety. He continued evacuating other wounded until the effects of the gas finally overwhelmed him. Stockham died in a hospital eight days later. For his heroic, selfless sacrifice, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

Bobby Wayne Abshire is another name every Marine (and firefighter) should know. Abshire graduated from high school in 1961 and enlisted in the Marine Corps. He spent nine years on active duty, serving three combat tours in Vietnam. In May 1966, Abshire worked as a crew chief aboard a Huey conducting medical evacuations. The call arrived one day for an infantry platoon in dire straits. Viet Cong trapped the grunts in an open rice paddy with more than half the platoon dead or wounded. Abshire’s pilot dropped in over the rice paddy, but enemy machine-gun fire drove the helicopter back. The pilot landed on his second approach. Casualties lay all around the helicopter. With no one else able-bodied enough to help the wounded to the chopper, Abshire jumped out. Enemy bullets dug into the earth all around him as he assisted two wounded Marines into the Huey. The chopper struggled into the air once more, delivering the casualties to safety.

Back at the airfield, ground crews deemed the Huey too shot up to fly again. Abshire unhesitatingly transferred his gear to a new Huey and volunteered to return. During eight separate trips into the rice paddy, Abshire left his Huey to collect fallen Marines. On one of these occasions, he found a grenade launcher and wiped out an enemy machine gun. Abshire and his crew evacuated 23 casualties from the field. For his outstanding resolve, courage, and dedication, Abshire was nominated for the Medal of Honor. His award was downgraded to the Navy Cross.

Abshire left the Marines in 1971 as a staff sergeant. He returned home to Texas and joined his father as a firefighter in Fort Worth.

“I remember one night we were coming home from a ballgame and a young kid had been hit on a bicycle. He had to stop and help,” Abshire’s wife, Jean, said in a 1984 Fort Worth Star-Telegram story. “He was always doing that. He’d tell me, ‘I could be the difference between someone living and someone dying because I know what I’m doing.’ ”

His belief proved true. In 1974, Abshire received his department’s meritorious service award for resuscitating a 2-year-old boy who nearly drowned in a fishing pond. Abshire served the Fort Worth community for 10 more years.

He performed his final act of service on Jun. 9, 1984. Driving home off duty, well after midnight, he happened upon a driver with a disabled vehicle stranded on the side of the road. Abshire stopped and walked back to the driver to help. While they talked, a drunk driver speeding down the road lost control as he passed by. The tires squealed and the headlights illuminated both men as the car careened off the road directly towards them. “Watch out!” Abshire yelled and shoved the other man out of the way. The vehicle missed the other driver but hit Abshire at full speed. He died an hour later at the hospital. He was 41 years old.

The willingness to place others before yourself is a hallmark trait of firefighters and Marines. Stockham and Abshire’s stories are just two examples of how this trait is interchangeably applied between both services and, for them, resulted in the ultimate sacrifice. Staff Sergeant Christopher Slutman represents a modern example, loved and remembered by both communities. Slutman served simultaneously as a Marine reservist and a 15-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York City. In 2014, he earned a medal for valor after climbing in full gear to a 7th floor apartment that was on fire, crawling through the smoke to locate a victim in the back bedroom, then dragging her to safety. He died in April 2019 at age 43 while wearing his other uniform. Assigned to “Echo” Company, 2nd Battalion, 25th Marines, Slutman deployed to Afghanistan where a vehicle-borne improvised explosive devise struck his convoy near Bagram Airfield. He and two other Marines died in the explosion.

Every Marine understands the incalculable value and personal meaning of sharing pleasure and pain with your brothers and sisters in uniform. Combat veterans rely on those who fought alongside them to interpret the lasting effects of their shared trauma and help each other heal. Uncanny parallels to combat unfold for veterans running calls in the civilian world, at times sitting around the dinner table with their shift mates working through the horrible calls they all hope to forget, other times doubled over in pain around the same table laughing as hard as they ever have before.

“I think my combat experience helped set me up for success but having it doesn’t necessarily make you a better firefighter,” reflected Angell. “Serving with the infantry was a hard, back-breaking job, but there is so much pride and camaraderie to come out of it. I see the fire department the same way. You are going to work. Anybody who has been on a single structure fire will tell you it’s probably one of the most physically demanding things you can do. When you get back you clean all your tools, clean all your gear, and get it ready for the next run, just like the Marine Corps. Do your mission and when it’s over, get ready for the next one. The camaraderie with your crew is huge. I quickly realized that, as a civilian, you’re going to run calls that are as bad, and maybe even worse, than combat. Having guys at your firehouse that you can trust to talk about things is key. That’s an ability I learned from the Marine Corps. You’re not a victim, you have 50 guys from your platoon who just went through everything you went through, and you’re not alone.”

“We in the military try to make our PTSD like it’s something that nobody understands,” echoed Meyer. “We try to make it like it’s this exclusive trauma nobody will get, like the only way you can understand me is if you’ve been in a gunfight, and that’s simply not true. I’ve ran two shifts back to back in the firehouse that made everything I saw in combat look like child’s play. The fire service is the closest thing that I have found to being with the type of people who are in the Marine Corps and that’s because the stakes are high. Nobody’s calling us when everything is great. We are there to be problem solvers for people in their worst moments. With that, it’s kind of like combat; you deal with combat and hard times with humor, and it’s the same thing in the fire service. There’s this unspoken support of each other, a sense of brotherhood where having each other’s back is unconditional.”

The dual identities of Marine veteran firefighters face off in friendly competition. The idea of, “once a Marine, always a Marine” proves challenging to assimilate with their new profession and equally defining lifestyle. Their trucks sport Marine Corps stickers down one side of the rear glass, while fire department decals fill the opposite side. Machine guns, bayonets, and MOS codes decorate their skin alongside Halligan bars, Maltese crosses, and “Never Forget” 9/11 tattoos. Their professional counterparts on active duty, meanwhile, remain singularly identified; they are Marines. But whether military or civilian, Marine firefighters or Marines who became firefighters, those who claim both titles enjoy the best job in the world and wear it with pride.

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.