Don’t Imitate, but Emulate: Peer Leadership’s Lasting Impression

By: Adam WalkerPosted on August 6, 2024

Editor’s note: The following article received an honorable mention in the 2022 Leatherneck Writing Contest. It is being re-published in honor of National Purple Heart Day on Wednesday, Aug. 7.

I served as a Marine infantryman for twenty-five years. During that time, I walked with legends and served with heroes. Some are recorded in our shared history, such as Medal of Honor recipient Corporal Jason Dunham. Others are less well-known, but no less great. The most influential leader in my professional life was a peer with whom I served as a young staff noncomissioned officer. His name was Staff Sergeant Enrique “Henry” Hernandez. I served with both of these fine men in “Kilo” Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines.

My first assignment had been on the East Coast with 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines where I served for five years and went on three deployments. I was a fire team leader on the winning squad of the 1996 Annual Rifle Squad Competition (Super Squad) and had been fortunate to have outstanding leadership. My first two battalion commanders were Lieutenant Colonel John Allen and Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Dunford. Both would go on to became four-star generals who had a tremendous impact on Corps and country.

I later checked into 3/7 in the summer of 2002 after a tour on recruiting duty in Asheville, N.C. Recruiting duty was challenging, but I finished well as a meritorious staff sergeant. As a new father I examined the demands of balancing career and family and considered leaving active duty. Like many who watched the towers fall on Sept. 11, 2001, I knew that a fight was coming, and I should be there. I requested orders to an infantry battalion in the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune. The enlisted assignments monitor told me, “You can go to 1/7, 2/7, or 3/7.” I responded “Uh … aren’t they all in Twentynine Palms?” He said, “That’s right … and that’s where you’re going.” I considered countering with mention of “a duty station preference following a Special Duty Assignment,” but thought that the coming fight would be in a desert. Why not train in the desert? I then requested orders to 3/7.

I pulled into the high desert that summer while the battalion was away in Victorville, Calif., for a month-long training package. By the time they returned to Twentynine Palms, I had completed the check-in process but was trying to figure out how to put together my gear. While I was on recruiting duty, the Marine Corps had transitioned from the ALICE packs (All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment) to MOLLE gear (Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment), issuing an instructional video on a VHS cassette with it. SSgt Hernandez grinned and said “I got you, bro.” He taught me how to put my gear together which began the first of many lessons I would learn from him. I knew early on that I wanted to be a platoon sergeant like Hernandez.

Hernandez had two tours in security forces and was a close quarters combat instructor. He’d been to more than a dozen schools and had assignments in 2/7 and 3/7 with several deployments, including Somalia. We may have held the same rank and billet, but Hernandez had more experience than I did.

The experience I gained in 2/6 provided a firm foundation upon which to grow. I had a high level of confidence in my experience and abilities, however, I recognized there was much to learn. In addition to new “deuce gear,” an entire family of radios emerged in the Fleet Marine Force while I had been away. Hernandez possessed the knowledge and experience I needed to “re-green” myself back in the grunts.

At that time a rifle company would typically have six SNCOs. The first sergeant, the company gunny, and four platoon sergeants. When I checked into the unit, Kilo Company had only two: the first sergeant and SSgt Hernandez. Hernandez was simultaneously filling roles as company gunny, platoon commander, and platoon sergeant while mentoring the young NCOs who were filling in as the other platoon sergeants. A week later he and the first sergeant went on leave saying, “You got it, ‘Walkie.’ ”

On Monday morning the battalion sergeant major yelled at me, “SSgt, why did Lance Corporal Smith get a seatbelt ticket?!” I had no idea who LCpl Smith was but replied, “Because he wasn’t wearing a seatbelt, SgtMaj.” I was kicked out of his office with a string of profanity and instructions to “fix Kilo.” A few days later I landed in his crosshairs for my poor execution of sword manual at a retirement ceremony. I became acutely aware that being a good platoon sergeant required much more than just being a competent grunt. Being a good platoon sergeant had to start with being a good SNCO.

When Hernandez returned from leave, I watched him closely, asked a lot of questions, and most of all, I did what he did. In leadership you cannot imitate, but you can emulate. Imitation is trying to be someone else. It is an act you cannot keep up when you are tired, stressed, or when the chips are down. It takes time to develop as a leader, but you have to be yourself. You emulate the qualities possessed by effective leaders. Hernandez had those qualities. He was physically fit, assertive, knowledgeable and incredibly professional. He could interpret situations and senior leaders and anticipate changes and then take action accordingly. He did all of this with humility. Hernandez was also the kind of guy who could immediately transition from “smoking and joking” to stone cold serious. He was balanced.

Hernandez never gave me bad advice. A few times he gave me advice that I disregarded to my own detriment. Once it was in a minor issue. I was in the barracks early ensuring reveille and morning clean-up were going on. I held formation and swung by the company office to give the first sergeant an update for the morning report. My platoon was about to right face for a “boots and utes” run up “Cardiac” and “Sand Hill” in the backyard of Twentynine Palms. I had a small pinhole in my T-shirt at chest level. As I passed Hernandez, he said, “Don’t let First Sergeant see that.” I balked and said, “We’re headed out to PT, it’s no big deal.” I reported to the first sergeant. He listened as I rattled off my update. In his characteristic fashion his eyes scanned methodically from my haircut to my boots. He then said curtly, “Good to go, Staff Sergeant. I see you again with a hole in your shirt, and I’m gonna rip it off your body”.

“Aye, First Sergeant.” I walked out to my platoon and Hernandez shook his head laughing. “I told you, bro.” I never did that again.

The next time I disregarded his advice, it was a much more serious matter. I tried to take care of a situation at my level, and I lied to the first sergeant. I count it my greatest professional failure. Hindsight provides clarity to a situation which seemed murky at the time. The event occurred during combat operations in Iraq during the time referred to as the “March Up” in 2003. We had been going for weeks on little sleep, crammed into the back of AAVs.

When the ramp dropped, we rushed out ready to engage the enemy. We never really knew where we were, but we knew Baghdad was north. Day blended into night then into another day. On one of those days, a lance corporal in my platoon lost a set of night vision goggles. The loss of serialized gear is really bad and could be an indicator of incompetent leadership. It was human error under arduous conditions, but the fact remains we lost them, and they could be used by the enemy. I told the company gunny but there was no time to search for them. We had orders to continue to push north.

A couple of weeks later as we were pulling out of Baghdad, Kilo Co was assigned a position in the desert to re-set. We got some rest and conducted accountability checks of our gear while waiting for follow-on orders to conduct security and stability operations. During my platoon site count, we discovered that one of the Marines lost a set of binoculars. “Binos” were armory-issued gear, but they weren’t serialized. I did not want to report that another piece of gear had been lost. I considered my options. I could just report it, knowing that some would begin to view this as a trend, and my reputation as a leader would be diminished. I also thought of various times where I had been taught that “SNCOs solve problems.” Another option was to temporarily hide the issue and remedy it myself. This would require me to initially lie and say we had all of our gear, then purchase a replacement commercially before the gear would be turned in after we returned home. It was feasible and tempting. I asked the other platoon sergeants for advice. Hernandez said, “Come clean, tell First Sergeant.”

I didn’t

After telling the first sergeant my platoon’s gear was all accounted for, I went back to my fighting hole. I sat there for over an hour feeling guilty. I walked back to the first sergeant. I told him I needed to speak to him, that I had lied. He looked at me and said, “I know.” I stood there in shame as he explained. One of the Marines in the platoon told the NCO who served as the armory custodian that we were missing the binos. The NCO passed on to the first sergeant who kept it to himself. He waited to see how I would handle the situation. He didn’t raise his voice but spoke sternly, full of disappointment. He then said this would remain between us, he would not tell the CO, but that trust had been broken and it would be a long road to restore it. I turned to go, but after a few steps faced him again. I said “First Sergeant, I do not take this lightly. This will never happen again. I failed, but I am committed to becoming the kind of SNCO that I should be.” He returned my gaze and said, “I hope so.”

I walked back to my position feeling dejected. An NCO from the platoon came running up smiling with something in his hand. He said “We found it! We found the binos!” My swirling emotions burst forth in a spew of anger and profanity. He left confused, wondering why I didn’t celebrate the good news. I gave the first sergeant the update. He simply said “Roger” and I walked away.

I orchestrated my own dilemma with my poor judgement. Upon learning that we actually did not lose the binos, I had the brief thought that I should have “stuck to my guns.” It would have resulted in no loss of face, but I knew inside that I would have pushed the envelope even further next time. I grew a lot from that experience. I stopped by Hernandez’s fighting hole. Unsurprisingly, he was cleaning his weapon. I told him all that had just transpired. He looked at me with empathy and without sounding the least bit condescending simply said, “I told you, man.”

Henry Hernandez taught me so many things. His example stays with me today. I learned the lasting power of peer leadership. Peers do not have authority over you, but they have tremendous influence on you. They know your vulnerabilities, they know your potential, and they know the real you. They possess the ability to challenge you and hold you accountable in a way no others can.

I’ve shared these lessons with many SNCOs during my remaining years in uniform by speaking in leadership panels, mess nights, graduations and birthday balls. They are shared here now because I have learned that leaders are rarely born, but always built. I am grateful one of those builders was my friend, 1stSgt Enrique Hernandez Jr.

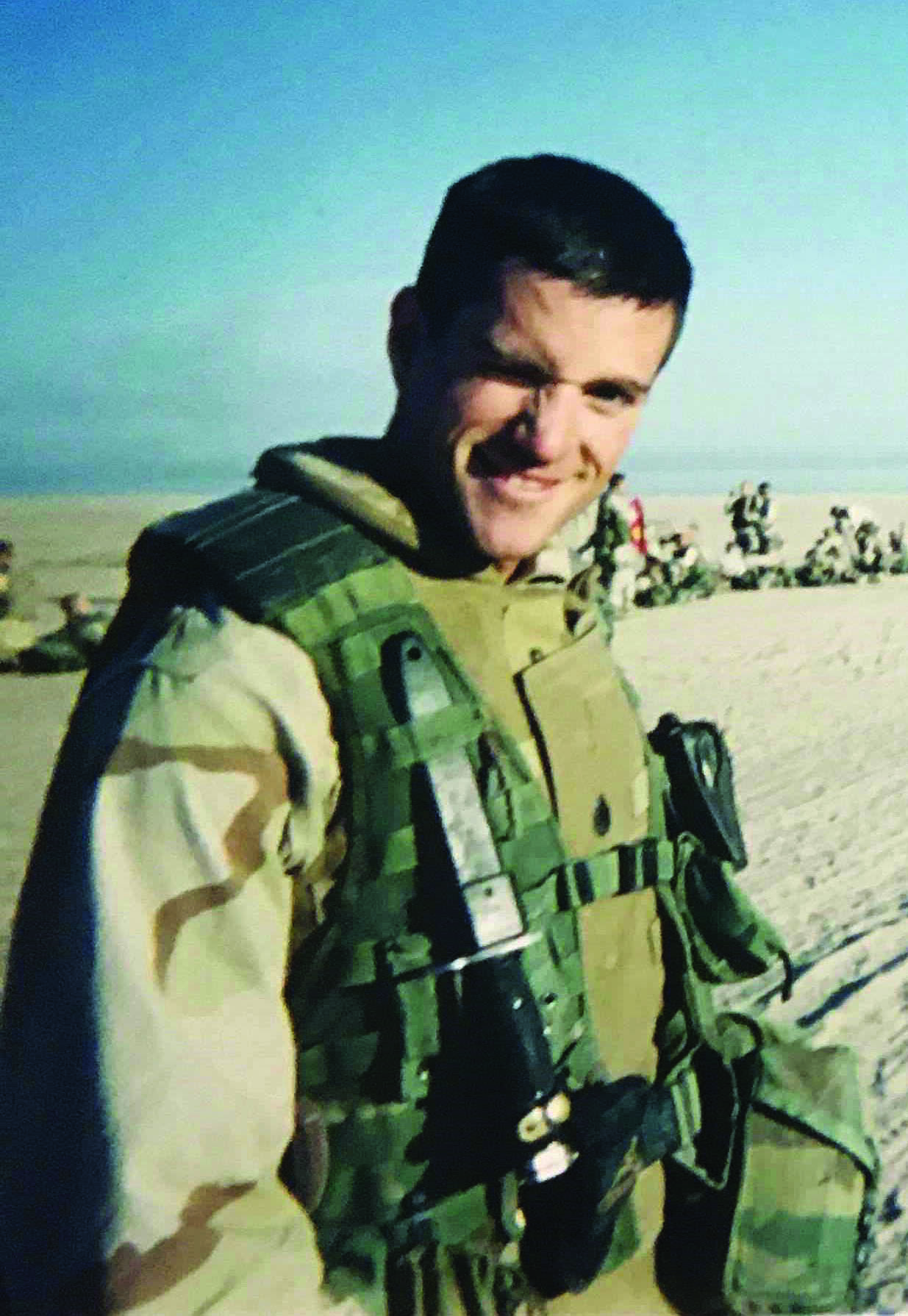

Author’s bio: Adam Walker served as a Marine infantryman for 25 years, retiring as a master gunnery sergeant with three tours in Iraq and a Purple Heart. You can read more of his work on his blog, takeitontheleftfoot.com.

.