Ambush in Haditha: A Footnote from Iraq, 20 Years Later

By: Kyle WattsPosted on April 15, 2025

Author’s note: To the Marines of MAP 7, thank you for entrusting me with your experiences and allowing me to share them. I hope what follows may appropriately honor the memory of your fallen and elevate your service toward the level of recognition it deserves. Semper Fidelis.

In late 2004, Sergeant Randall Watkins faced the most unusual task of his Marine Corps career. An active-duty infantry squad leader turned prospective officer candidate, now Watkins found himself in a POG (Person Other than Grunt) reserve unit with orders to create an infantry platoon out of the cooks, clerks and mechanics surrounding him.

Watkins left active duty earlier that year to finish college and achieve his goal of becoming a Marine officer. Tumultuous events in Iraq, however, swayed his decisions elsewhere. The war would end soon, he believed. If he wanted in on the action, he had to get back in uniform and over there now. Watkins dropped out of school in his home state of Texas and joined the nearest reserve unit, 4th Reconnaissance Battalion, out of San Antonio. Despite his infantry background and active-duty experience, 4th Recon did not have a place for him. The battalion shipped Watkins and numerous others like him to Twentynine Palms, Calif., to fill out another reserve unit preparing for war.

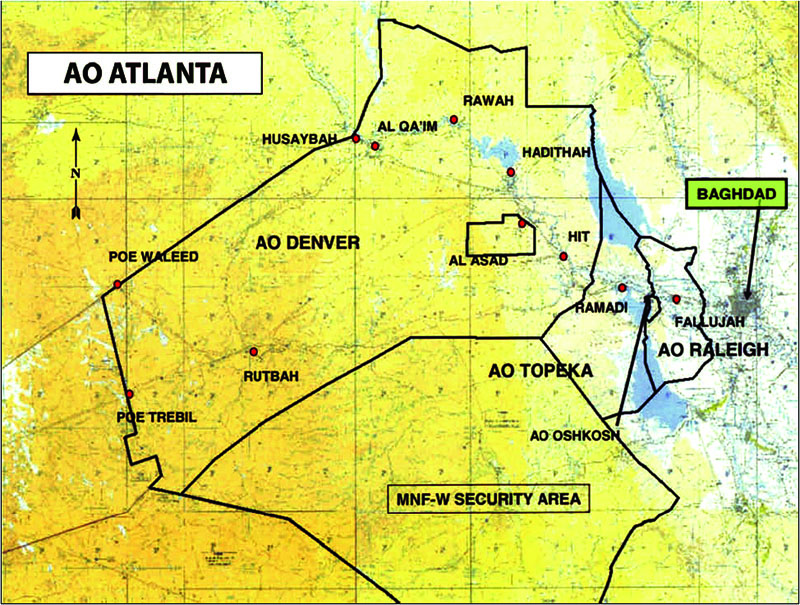

The 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division, gathered there for predeployment training and time was running short. Based in Ohio, the battalion was activated to fight in Iraq and called up Marines sprinkled across the country. Even now gathered at full strength, 3/25 came up short-handed. Officers planning the deployment faced another problem. Their future area of operation spanned a huge swath of Anbar province, the Wild West of Iraq. To adequately cover the zone, they needed highly mobile, heavily armed small units capable of speeding throughout the area at a moment’s notice. The battalion’s leaders devised the Mobile Assault Platoons (MAPs) to fill the gap.

When Watkins showed up, 3/25 assimilated him into Headquarters and Service (H&S) Company. He loathed the prospect of an Iraq deployment trapped inside the wire with headquarters, until one day when everything changed. Battalion command tapped Staff Sergeant Michael Brady, another former infantryman and longtime 3/25 member, to be the new platoon commander for MAP 7. Watkins, by coincidence in the company office as the conversation took place, was named platoon sergeant. In addition to its “mobile assault” function, an ambiguous role still being defined, MAP 7 would act as the battalion’s personal security detail for the officers and senior enlisted leaders traveling around Iraq. Whatever its role might turn out to be became the primary problem for Brady. Watkins’ responsibility was to create the platoon from scratch.

The available pool from which to select proved woefully limited. Infantrymen were not available. Instead, the battalion offered mechanics, truck drivers, cooks or any other Marine Watkins wanted from H&S Company. He began with the highest scores on the rifle range and physical fitness test. Beyond those basic qualifications, he scrutinized civilian jobs, looking for any Marine employed or trained in anything remotely “Marine.”

The candidates’ lack of face value belied the prior service or civilian roots of numerous H&S Marines that distinguished them as immediate choices. Like Watkins, most joined the Marines however they could to get into the fight. Many selectees came from the batch of Texans pawned off from 4th Recon. Corporal Zane Childress very nearly earned himself Non-Judicial Punishment for the hell he raised over being assigned as a radio operator with H&S rather than an infantry platoon. The comm shop gladly gave him away. Sgt Aaron Cepeda, a cook by trade, was also a double major in chemistry and biology, well on his way to medical school, and one of the smartest people Watkins ever met. Sergeant Michael Marzano was a former active-duty mortarman who rejoined in the Marine Corps Reserve and wound up a bulk fuel specialist.

Lance Corporal Lance Graham towered over the Marines around him, standing nearly 6 1/2-feet tall and weighing almost 250 pounds without his gear. He filled a slot in the supply section but could shoot as good as any Marine Watkins knew.

“Whoever that reserve recruiter was for 4th Recon, he deserves an award because he got some rockstars into some shitty billets,” Watkins mused recently. “People got labeled with their bullshit reserve titles, but I had some real studs.”

Ohio natives volunteered as well. Four mechanics out of the motor pool and fast friends from Cleveland interviewed with Watkins. LCpl Todd Corbin stood out as a no-brainer for selection. In his early 30s, nearly a decade older than most others, Corbin served as a deputy sheriff and SWAT Team member. Watkins also brought on LCpl Mark Kalinowski, the brightest and hardest working mechanic in the motor pool, and Cpl Jeff Schuller, a high school and college wrestler. To set himself apart from the bulk of Ohioans volunteering, Schuller fabricated part of his personal history, adding a background in military police, banking that Watkins would not check into it. The ploy worked and Schuller was accepted. Corporal Stan Mayer volunteered once he learned Schuller and the rest of his friends had left H&S to join MAP 7. Watkins accepted Mayer based on his training, having completed the first half of Platoon Leader’s Course on his way to becoming a Marine officer, and having trained extensively with the U.S. Army National Guard’s 19th Special Forces Group in Columbus.

For the next few months, Watkins worked the platoon day and night.

“Mobile Assault Platoon 7 was not infantrymen, it was ‘every Marine a rifleman,’ ” remembered Mayer. “Watkins was not happy that he didn’t have infantrymen, and he would be damned if he didn’t make us into the infantrymen he wanted. He treated that work up like a deployment. He would not let us sleep. There was not one minute he let go by that we weren’t learning. What that really did was it made the platoon have a special chemistry.”

The battalion arrived in Iraq on March 6, 2005, and proceeded to Haditha, 150 miles northwest of Baghdad. The Marines occupied the Haditha Dam, a massive, multi-level concrete structure situated across the Euphrates River.

Other towns in Anbar Province such as Fallujah or Ramadi already gained notoriety since the 2003 invasion. Haditha had yet to cement its place in the history of the Iraq War.

MAP 7 fell into a repeating cycle. The platoon spent most days on the road conducting route reconnaissance, setting up observation posts or ferrying the battalion commander around the AO. Periodically, the platoon received a scheduled day of rest. Despite the size of the dam, living space was cramped. Marines piled into dormitory-style rooms, some with balconies overlooking the river and the urban center of Haditha several miles south. They filled their off days cleaning weapons, tinkering with their trucks and chain-smoking cigarettes on the balcony while heckling sister platoons doing the same.

When not on rest or a planned mission, MAPs took turns as the battalion Quick Reaction Force (QRF). The duty platoon stuck close to the dam, ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. If nothing bad happened, QRF days became another day of rest. Platoons could never relax, however, in the presence of the phone. Marine communicators strung telephone wire down the MAP hallway inside the dam, ending at a single, red telephone. Like the ubiquitous “bat phone,” the QRF phone existed for one purpose.

“It’s not like it was ever your mom calling,” said Jeff Schuller, today a major and active-duty infantry officer. “It’s never good news. You’re just sitting there reading, watching stupid movies, trying to think about anything other than what you’re doing. That thing would ring and hearts would just drop. I don’t think I’ve ever hated an inanimate object in my life as much as I hated that phone.”

The phone rang a lot. Any time the battalion had troops in contact, the QRF deployed to assist. Any time a mortar round struck the dam, the QRF investigated the point of origin. Any time another platoon struck an Improvised Explosive Device (IED), the QRF deployed to recover the vehicle. By the time a tour of duty ended, platoons coming off QRF gleefully passed the phone to the next in line like a hot potato.

MAP 7 had its first casualty less than two weeks into the deployment when a humvee in the column hit a landmine. The explosion severed the leg of LCpl Aaron Rice seated inside the vehicle. The vehicle was destroyed, but thankfully, Rice survived. At the motor pool in Al Asad, the platoon sought another humvee as a replacement. The Motor Transport chief offered instead an up-armored, heavily modified 7-ton. The truck previously served as a command vehicle. The gutted cargo area had new seating and tables installed.

Marines welded pintle mounts around the exterior of the bed, enabling the addition of several machine guns. When fully outfitted, the truck bristled with gun barrels like an old WW II bomber. A 7-ton was a poor platform for casualty evacuations and the antithesis of “mobile” or “assault,” but the platoon would have to make it work. As one of the only Marines with a license to operate the vehicle, Todd Corbin volunteered to drive.

By the beginning of May, MAP 7 covered hundreds of miles around Anbar province. The platoon encountered IEDs and traded fire with the enemy in numerous encounters. Despite several close calls, Rice remained the only casualty. MAP 7 returned to the dam on May 6 to rest and refit once again following another 24-hour patrol. As the sun rose on May 7, the exhausted Marines sipped coffee and tried to relax, waiting out the daylight hours. Again that night already, MAP 7 was scheduled to depart after dark to an overnight observation post. To make matters worse, QRF duty fell to them once again for the day. A significant portion of the battalion deployed west toward the Syrian border in preparation for Operation Matador, a major offensive scheduled to begin the next day. MAP 7 remained in the rear with a skeleton crew at the dam.

In the morning, Mark Kalinowski located Schuller in his room and hounded him to get their truck down to the motor pool. Earlier that week, Schuller spotted brand new humvee turrets, boxed up and waiting to be installed. Kalinowski adamantly wanted the upgrade. As the vehicle gunner standing exposed above the roof, his life depended on it. A cylindrical metal shield formed his current turret, like a large barrel cut in half, offering meager protection. The upgraded turrets were constructed of true armor plating, spaced and angled for maximum protection. Schuller chafed at the idea, wanting instead to relax for the remainder of his day at the dam, but eventually he capitulated. The two spent the next four hours constructing and installing the upgrade. Kalinowski mounted his M240G machine gun and tested the turret’s operation. When traversing the gun left or right, only a small 3-inch gap opened on either side of the armor plate in front of him. The surrounding armor felt significantly better than his previous accommodations. The true level of protection, however, would only be revealed in combat.

The Marines prepared for their overnight mission as the sun dipped in the western sky. Watkins sat with Cepeda in an internet cafe penning digital Mother’s Day cards to send home. A dull “boom” suddenly thudded outside. Watkins immediately recognized it as an enemy mortar striking the dam. He ordered Cepeda down to the rest of the platoon to start getting ready to roll out. Watkins made his way to the Combat Operations Center (COC) to find out what they knew. Deep inside the dam, the QRF phone rang to life.

The platoon assembled with their vehicles at the gate leading out the east side of the dam. Insurgents routinely fired mortars from the eastern side of the Euphrates then fled into the open desert. Tonight, however, the COC instructed Watkins to turn his column around and stage at the west gate. This mortar attack originated in Haditha on the western bank. Watkins sensed something off. This was a new tactic. The COC ordered Watkins to stand by and wait for a pair of tanks to support his column.

While MAP 7 waited, machine-gun fire echoed to the south. Word spread of a sister platoon several miles downriver on the eastern bank taking fire from a palm grove in Haditha on the western bank. Marines in riverine patrol boats sped downriver from the dam and blasted the palm grove with machine guns and automatic grenade launchers. Each time the enemy fire ceased and the boats departed, mortars soon resumed firing toward the dam and insurgents shot at the MAP on the eastern side.

“We heard the radio traffic start coming through and I was thinking why would someone with an AK-47 start shooting at a gun truck with a machine gun on top?” Watkins said. “It’s suicide. This was obviously something we had never seen before.”

The platoon waited nearly two hours for the tank support to arrive. Despite their frustration over the delay, the Marines’ spirits remained high. Mayer was certain tonight would finally be their opportunity to actively take the fight to the enemy. The sentiment spread. Two Marines from outside the platoon joined at the last minute, a staff sergeant from the armory and a cook eager for his first chance to leave the wire.

Darkness enveloped the dam by the time the tanks arrived. Mayer fired up his humvee. Watkins sat in the vehicle commander seat next to him. One by one, the three humvees of MAP 7 fell in behind the first tank and surged out the gate. Corbin drove his 7-ton in the middle of the line with the last tank bringing up the rear. The palm grove was only 15 minutes away in the heart of Haditha.

The column drove south paralleling the river. Mayer followed the tank ahead through his night vision goggles. He passed a single vehicle on the side of the road with hazard lights flashing at the city line, but no one else appeared anywhere in sight. On the radio, their sister MAP reported the enemy broke contact and disappeared. Haditha fell silent.

Watkins tracked the column’s position on his global positioning system. It lagged and failed to provide him a real-time position as they crossed into the city. By the time it finally updated, Watkins realized they passed their objective in the darkness. He halted the column. Their only option now was to turn around, and to do it as quickly as possible. Six-foot walls line the street on either side of the road. Street lamps dimly illuminated the Haditha hospital rising above the wall on their left, with narrow alleyways disappearing into the darkness down either side of the compound. It was a bad spot, and everyone seemed to know it. Chatter over the internal radios ceased.

“It was night so no one really should have been around, but I mean no one was around,” Mayer remembered. “Like in an old western, the rocking chair is rocking but no one is in it. You knew something was going to go down.”

The tanks covered the road to the south as Marines dismounted and the convoy reversed direction. Even the smaller humvees required multi-point turns to spin in the street and point north once again.

Watkins dismounted to provide security and guide his humvee through the dark. He glanced at Mayer before exiting the vehicle.

“I’m gonna go run the rabbit and draw some fire.”

An ambush felt imminent. Watkins figured he would trigger it by exiting the vehicle. With Graham in the turret above watching over him, he remained confident. He reached back and elbowed Graham’s shin standing behind him.

“Let’s go get some.”

Mayer weaved his way around and back through the rest of the vehicles. He parked near the intersection at the corner of the hospital, covering the rear of the column. Behind him, the rest of the platoon began turning around.

“I wanted to get into a good spot for Graham to cover us with his machine gun,” Mayer said. “I was asking him, ‘Is this good? How about this Lance?’ All of the sudden, I heard Lance screaming, ‘Stop motherf–ker! Stop!’ I thought he was screaming at me so I stopped. I thought we had somehow rolled onto an IED he saw that I didn’t. The last thing I heard was Lance spinning the turret, racking his machine gun, and just beginning to open fire when an eruption occurred that was just like a hard reset.”

Unseen by Mayer, a suicide bomber in a van packed with explosives emerged from the darkness, careening down the alley. The van plowed into a wall near Mayer’s humvee and detonated. The awful blast leveled walls and buildings around the intersection. An impenetrable dust cloud covered the area, and a ball of fire exploded upward like the sun rising over the Euphrates.

In his humvee a few dozen meters away, Schuller had just completed his turn. He found an unmolested patch of concrete and drove off the road on top of it. No insurgent, he thought, would go through the effort of pouring fresh concrete over a planted IED. When the suicide bomber detonated, all four wheels of Schuller’s vehicle lifted off the ground. Schuller was dumbfounded and angry, believing he had in fact parked directly over an IED. Behind him, Kalinowski slumped down beneath the turret. A chunk of shrapnel flew through the gap beside his machine gun and obliterated his wrist. Schuller crawled through the cab, closing all the doors that hung open. Gunfire and screaming filled the air. Schuller took Kalinowski’s place in the turret. Outside, dead or wounded Marines littered the street. The remaining hulk of Mayer and Watkins’ humvee glowed a fiery orange through the dust cloud. Muzzle flashes illuminated the hazy outlines of sandbagged positions across the roof line of the hospital. Without hesitation, Schuller spun the turret and opened fire. He poured an unending stream of lead into the building as rounds pinged off the metal around him. The upgraded turret might now save his life rather than Kalinowski’s.

When the blast pressure passed over, Mayer convinced himself that he was not dead. He couldn’t hear. He could barely see or feel. He reached out from inside himself, working through a mental checklist of body parts to rediscover and determine if they were working. He felt pain. His entire body felt flash-fried, like the worst sunburn one could possibly endure. He found his door blown open and lifted himself out of the vehicle. He turned back toward his seat. The ruined humvee sat low on four flat tires with the roof line at chest height. Ricocheting bullets sparkled brightly off the metal top without a sound.

Confounded, Mayer gazed upward toward the hospital. The building disappeared, veiled in dust. Hovering muzzle flashes twinkled in the air, bedazzling the dirty sky.

Amid the sparkling rounds, a perfectly flat surface stretched out in front of Mayer where the armored turret had once sat. Fire licked up through the hole where the gunner once stood. Where was Graham? The question zapped Mayer back to reality.

“I dropped to the ground and scrambled around on my knees until I found my rifle which had been blown out of the truck,” he said. “I racked a round into the chamber then sat there and took cover. I guess I was waiting for somebody in charge to tell me it’s OK to shoot my rifle because I’d never shot it without a Marine telling me to. I just sat there listening to the rounds slap against the humvee until I realized this was not the rifle range. So I stood up, aimed at the muzzle flash, and pulled the trigger until it went away. After that moment, everything became less ethereal. Everything was all just like a dream state until I had that realization that this was combat.”

Dismounted and standing nearby, Watkins absorbed shrapnel across his body. Enemy gunfire followed the explosion. Two rounds struck the plate in Watkins’ body armor and one punched through his shoulder in the same area where a large piece of metal tore through moments before. The resulting wounds looked like someone dug out his left breast with an ice cream scoop.

“I went down and I couldn’t move,” Watkins recalled. “There was rubble everywhere. I could hear people screaming. I couldn’t feel my left arm or my left leg, but I still had my rifle in my hand. I emptied the magazine but couldn’t reload another. Rounds were impacting in the street all around and I could see muzzle flashes on both sides of the street. I basically just laid there waiting for a bullet to hit me in the head. I tried to yell, but nothing was coming out. Across the street, I watched Childress go down but get right back up and go to a Marine who was screaming in pain.”

Todd Corbin materialized through the dust cloud, standing over Watkins. He heaved the grievously wounded sergeant over his shoulder and ran back to the 7-ton. As he loaded Watkins in the bed, a tank next to them fired a main gun round into another vehicle approaching the ambush site. Concussion waves swept over the Marines in the back as they dragged Watkins to the front of the bed. Outside, Corbin found Childress leaning over a Marine with the muscles shorn from the back of both legs and femurs exposed. In the darkness and rubble-strewn chaos, Childress inadvertently looped a downed power line inside a tourniquet placed on the Marine’s leg. The line snagged and went taught as Childress and Corbin dragged him away. They freed the line, replaced the tourniquet, then placed the Marine in the 7-ton with Watkins.

The cook who joined the mission at the last minute stumbled out of the back seat of Mayer and Watkins’ humvee. He found Graham lying motionless nearby beneath a pile of building rubble and twisted turret armor. Mayer tried to move Graham’s body but was unable to pick him up. Mayer told the cook to stay put and set out in search of the remainder of the platoon. He ran through a cloud of smoke and dust to where the other vehicles sat mixed together on the street.

“The scene that I saw in front of me was so stunning,” he remembered. “All the humvees were destroyed, the 7-ton was billowing smoke, pools of oil on the ground had caught fire, power lines were on the ground, there were bodies and casualties lying around, there was Jeff on the turret in the background just yanking back on the trigger of his 240; it was like a scene from a movie. It was total apocalyptic chaos.”

Mayer came across a Marine leaning over Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class Jeffery Wiener, the Navy corpsman assigned to MAP 7. Mayer prepared a tourniquet and checked the doc for wounds but found no external bleeding. The blast pressure alone produced significant internal damage. Wiener passed away as Mayer swept across his backside checking for injuries.

Mayer continued on, finding Corbin standing outside his 7-ton.

“When I got up to Todd, I must have been screaming at him,” Mayer said. “I couldn’t hear shit, my eardrums were melted, I had just found Lance’s body, Doc just died in my arms, I ran past another body that I couldn’t even tell who it was. I ran up to Todd and grabbed him and just started screaming some sort of gibberish at him. He was just like, ‘you need to calm down son.’ He’s a lance corporal, 30-something-year-old sheriff deputy, just lawless. You could not get him to do anything he didn’t want to do. I love him, he’s my brother for life, but when he told me to calm down, I wanted to f–king kill him.”

The pair set out together collecting more casualties. Mayer fired at muzzle flashes in the dark while Corbin focused on moving the dead and wounded. They first returned to the body Mayer earlier passed, later identified as Sgt Marzano. They brought him to the 7-ton and went back for Doc Wiener. At one point, Mayer passed close by the humvee where Schuller stood protecting the entire column with his machine gun.

“I was completely black, charred and covered in dirt,” Mayer remembered. “I looked like I just stuck my finger in an electrical socket powered by an atom bomb. When Jeff saw me, he yelled, ‘what are you doing here?’ I shouted back, ‘what the hell do you mean?’ He says, ‘where is the chaplain at?’ The whole time we’re having this conversation he is continuously firing the 240 into the hospital. I realized he didn’t recognize me. I was like, ‘what the f–k are you talking about? It’s me! Stan!’ After a second, he giggles and goes, ‘oh shit! I thought you were dead! Awesome buddy!’ We had a Marine who was the assistant to the battalion chaplain and he was black. Jeff saw me and thought that the chaplain came out and I was his assistant. He thought I was dead. He knew I was dead. It made more sense to him that I was the black Religious Program specialist than his best friend Stan.”

Schuller stood exposed continuously in the turret. Beyond the rifle fire from Mayer, Childress, and a few others still standing, Schuller’s machine gun stood alone as the sole weapon keeping the enemy ambush at bay. He burned through several hundred rounds in rapid succession. Every time an ammo can ran dry, Kalinowski readied and passed up another from inside the humvee.

Whenever they paused to reload, Kalinowski handed him an M16 to keep up the return fire. The muzzle flashes morphed into visible insurgents on the street.

“I shot one guy with the 240 standing in the front doorway of the hospital only 20 or 30 meters away,” Schuller said. “It was very obvious that guy was dead in this life and the next. I vividly remember thinking, ‘oh wow, this machine-gun works,’ like it was an epiphany. Kind of like the first time I ever jumped out of an airplane and the chute opened, I remember yelling out, ‘wow! I can’t believe it worked!’ ”

The gun kept working. Enemy fire broke under Schuller’s relentless barrage. Still, rounds struck the humvee all around Schuller and kicked up dirt in the street around Corbin and Mayer as they recovered casualties. At one point as Mayer worked on a casualty next Schuller’s humvee, an insurgent appeared in the window directly behind him.

“Get down!” Schuller screamed.

He opened fire just a few feet over Mayer’s head, cutting down the enemy soldier.

For nearly 45 minutes, Corbin and Mayer sprinted around the ambush site filling the 7-ton with dead and wounded. Childress assisted while zeroing out the radios and sensitive equipment in each vehicle and recovering weapons and gear. Schuller burned through more than 1,500 rounds. When the machine gun ammo ran dry, he resorted solely to his M16. When that ammo ran out, he pulled his pistol, dropping at least one insurgent on the street.

Throughout the engagement, Mayer remained focused on getting back to Graham. The humvee burned and exploded over and over again with rounds cooking off inside as Mayer worked with Corbin to rescue other Marines. At one point, a tanker told Mayer to get one of the humvees out of his way so the tank could move into position and lead them out of the area. The destroyed vehicle was barely operational, but Mayer lurched it forward against a wall.

When he stepped out of the driver’s seat, he found Aaron Cepeda’s body lying next to the humvee. Childress arrived and helped recover Cepeda’s body. Like Mayer, at some point through the ambush, Childress attempted to pull Graham from his location near the burning humvee. Already wounded with shrapnel across his face, neck, and right side, a bullet tore through his left leg as Childress leaned over Graham. By the time all remaining dead or wounded were loaded into the 7-ton, recovering Graham seemed nearly impossible.

Schuller and Kalinowski finally abandoned their humvee and loaded into the 7-ton. Corbin hopped back in the driver’s seat. He activated an emergency air compressor to keep the ties inflated enough to limp the 7-ton out of the kill zone.

Another quick reaction force speeding south from the dam entered Haditha less than 1,000 meters away. Mayer begged Corbin to stop for one final attempt to recover Graham. With numerous wounded aboard, including one Marine with tourniquets on both legs and Watkins bleeding out through a gaping hole in his chest, the Marines pressed on. They passed their rescue column on the way out of Haditha and pinpointed Graham’s location at the ambush site. The relief force fought their way into the ambush site and recovered his body. The three destroyed humvees remained.

When the 7-ton stopped inside the dam, a sea of Marines enveloped the bed. Out of 16 Marines on the patrol, 11 were wounded or killed. Rescuers threw Mayer and Kalinowski onto the same medevac chopper. A zipped body bag lay near their feet. Neither knew who it contained, or who else may have died. Until that moment, both believed each other perished in the ambush. They arrived at Charlie Surgical in Al Asad where staff members efficiently stripped the Marines and checked them for holes. With additional wounded already arrived and more incoming, all hands stood on deck. They lined the hallways, heads swiveling and mouths agape as Mayer and Kalinowski rolled past. Mayer noticed two nurses weeping in each other’s arms. He looked toward Kalinowski.

“What the hell are they crying about?”

“I think us buddy.”

Childress flew out on the same chopper as Watkins. Despite shrapnel wounds across his face, neck and legs, and a gunshot wound, Childress remained unfazed. Now, he continued minimizing his injuries in the presence of his gravely wounded platoon sergeant.

“I don’t know how Watkins didn’t die,” he remembered. “I mean somebody blew him up and shot him at the same time, then he sat in the back of that 7-ton stuffing gauze into his own open-cavity wound. How did he live and breathe through that? He’s a machine. When our Blackhawk got to the hospital and they took us inside, I could see him starting to fade. When we got into the same room, I heard his monitor flatline. I freaked out. They shocked him and brought him back, but he died for a split second there in the hospital.”

Corbin’s swift actions in scooping Watkins off the ground and returning him to the relative safety of the 7-ton played a key role in Watkins’ survival. Indeed, Corbin made more than five trips back and forth through the ambush site carrying, dragging, or assisting casualties back to his vehicle. Miraculously, he remained uninjured.

Mayer stuck by Corbin’s side for the remainder of the ambush once they met up, surviving the hail of gunfire in addition to walking away from the initial blast. He spent two weeks at the hospital in Al Asad before returning to Corbin, Schuller, and the few other Marines remaining from the original MAP 7 group.

“When I got back to the dam, the platoon was all gone,” Mayer said. “They had already gotten a shipment of combat replacements, a batch of 19-year-olds straight out of God knows where, and they were already out there patrolling again with Jeff and Todd. My little cubicle of a room at the dam was Mike Marzano, Aaron Cepeda, me and Sgt Watkins. I got back and they were all gone. I was staring at two empty racks, those guys were dead. The one above mine, that guy was hit a bunch of times and he’s gone. I spent like a week in the dark smoking cigarettes with their ghosts until the platoon finally got back and Jeff came and found me.”

SSgt Brady named Mayer as Watkins’ replacement for platoon sergeant. He and Schuller took the lead for the remainder of the deployment conducting operations and raising their new replacements. Their experience on May 7 dictated their every decision for the remaining five months of the deployment.

The ambush served as a catalyst for a marked turn toward chaos in Haditha. Violence escalated through the summer and on Aug. 1, six Marine Scout Snipers were overrun and killed in their hide on the outskirts of the city. Operation Quick Strike was launched by 3/25 in response. Two days later at the outset of the operation, an AAV struck an IED just outside the city, killing 14 Marines and an Iraqi interpreter loaded inside. The tragedy marked the start of a three-day period in which the battalion suffered 19 KIA. By the time Mayer, Schuller and Corbin rotated out of Iraq with the rest of the battalion in September, 3/25 suffered 48 total killed and more than 150 wounded.

The ambush on May 7 endures today as a defining event for the Marines who experienced it, though it can hardly be found as more than a footnote in broader histories of the war. The personal awards that emerged reinforce its significance. Mayer received a Navy Commendation Medal with combat “V” for his actions, while Childress received a Bronze Star with “V.” For his outstanding courage and dedication remaining in the turret and suppressing the ambush, Schuller received a Silver Star. For his actions moving repeatedly around the kill zone and rescuing his fellow Marines, Corbin received the Navy Cross. Today, the survivors serve their families, communities, and some still the Corps on active duty, guided by the lasting impressions developed in the wake of the attack.

“That incident has kept the reality of what we do as Marines at the front of my mind,” Schuller reflected. Today, he serves on the training staff of Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, Twentynine Palms, Calif., preparing Marines for deployment. “All I think about every day while we’re training Marines is ‘are we getting mentally and physically prepared to win wars.’ In my mind, that should be our priority; to win wars and bring our brothers and sisters home.”

“This thing has completely changed us,” Mayer reflected. “Jeff and I used to say, ‘don’t let this thing define us. If we’re still talking about this 10 years from now, I want you to punch me.’ Yet here we are 20 years later. No matter what we do, these 45 minutes in May back when we were kids defined us and always will. Everything we do now is on behalf of those guys who didn’t make it. That’s the driving force. Lance Graham is dead, and so is Mike Marzano, Aaron Cepeda, and Jeff Wiener. So are 44 other of our buddies in the battalion, not to mention everyone else in that war. Those four guys I knew personally, and they were so much better than us. Far be it from me to waste my bonus life feeling bad for myself or being an asshole. They don’t get that choice.

“We are much older men in a much different place in our lives, but a lot of us have not processed our shit in the right way. A lot of us are still struggling, and that breaks my heart. You can’t just bring everyone to the right place, you have to seek it out yourself. I’ve found different ways to process my shit by exposing it, talking about it, and working through it, but I still don’t exactly know what my shit is. This story, weaving together disjointed strands into a solitary rope, illuminates the truth of what actually happened to us, maybe for the first time, because those of us who were there will talk about anything but, and the truth is the last gate between us and the peace we all seek.”

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.