1/27 on Iwo

By: John A. Butler IIIPosted on June 15, 2025

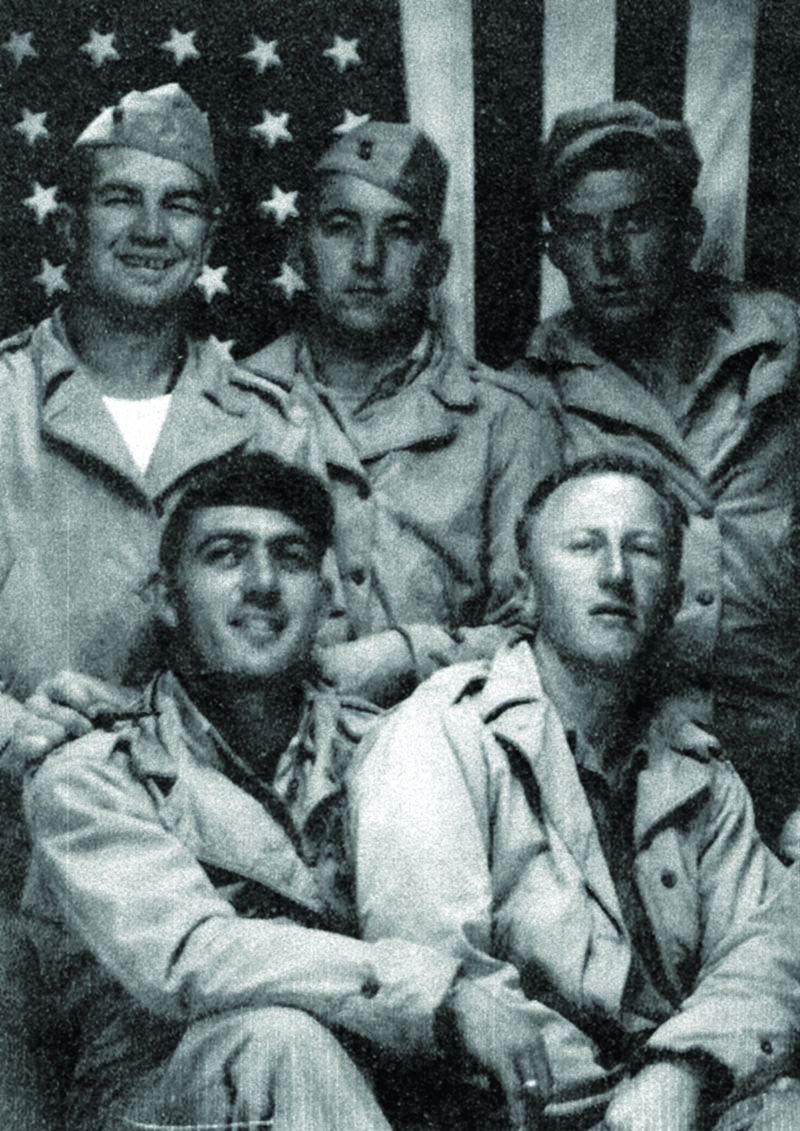

The 1st Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment was one of nine infantry battalions of the 5th Marine Division activated in early January 1944 at Camp Pendleton, Calif. Salted with disbanded Raiders, ParaMarines, and other combat veterans from earlier Pacific battles, the battalion was destined to play a crucial role in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Among the veteran NCOs reporting to 1/27 was Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, the Guadalcanal national hero, who requested relief from a national bond tour so he could get back in the war. The quality of training and battle leadership provided by the presence of these veterans was invaluable.

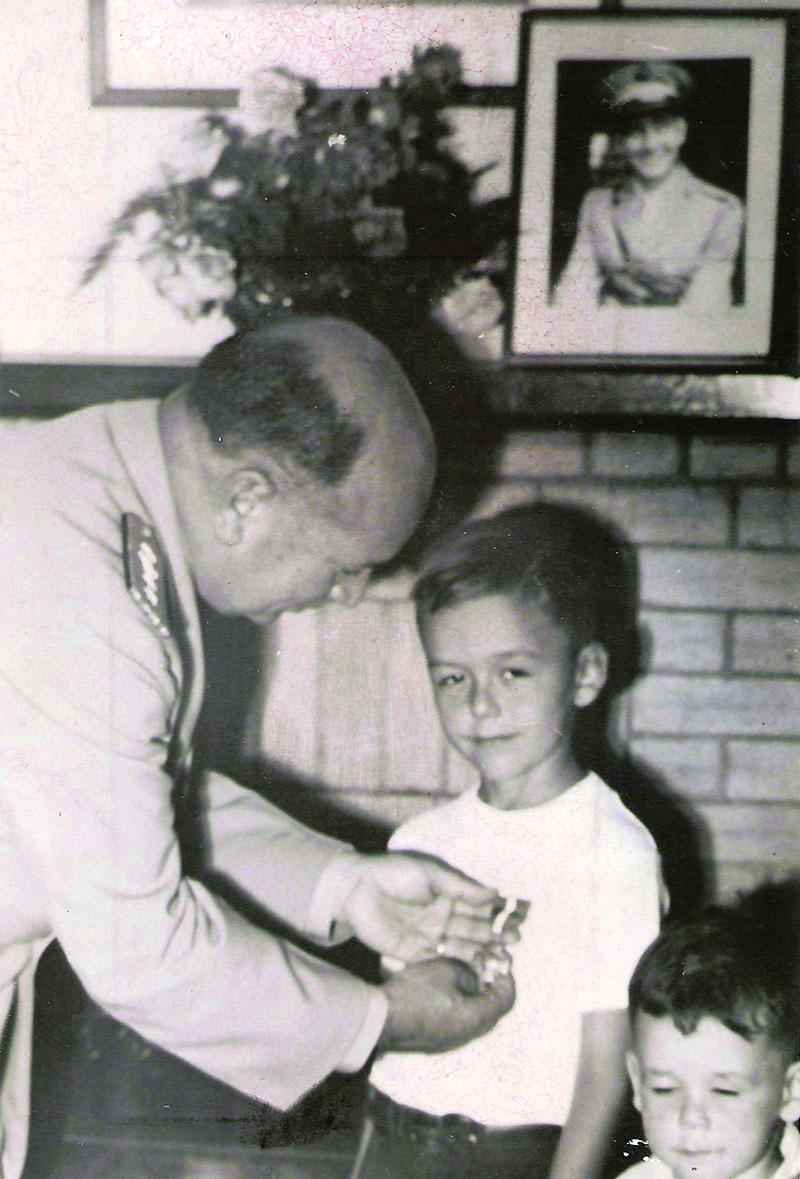

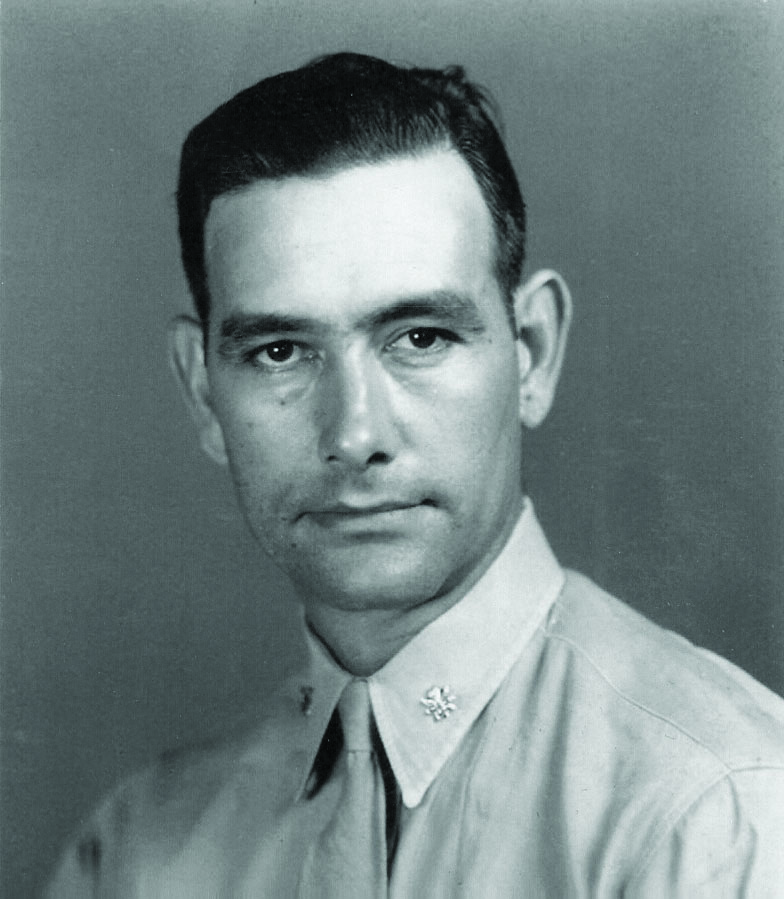

Assigned to command the battalion was Lieutenant Colonel John A. Butler, a native of New Orleans, La., and a career Marine who had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1934. Butler had early sea duty in the Caribbean, where his linguistic skills led him to work in naval intelligence and as an attaché in the Dominican Republic. He also had duty with 1st Bn, 5th Marines from 1938 to 1940. Fresh out of Command and Staff Course, though not yet having experienced Pacific combat, this seasoned Marine officer was eager and prepared for command.

With the arrival of new men and veterans, training progressed from individual combat training to unit training. The battalion, and the entire division, trained for serious amphibious assault combat and selected “The Spearhead” as their nickname and division shoulder patch.

On Aug. 12, 1944, the 27th Marines left San Diego for Camp Tarawa in Hawaii. There in the high windswept volcanic desert, the battalion completed its final phase of training before combat. On Dec. 31, the battalion deployed for rehearsal landings at Maui, followed by a final liberty in Pearl Harbor before sailing westward aboard the USS Hansford (APA-106). Two days out of Pearl, LtCol Butler announced to his battalion that they were destined for Iwo Jima, a Japanese island objective closer to Japan than any other to date. He also told his men they were a designated assault team for the D-day landing. A sober silence fell over the battalion.

After stopping at Eniwetok for some swimming and mail call, Hansford proceeded to Saipan, where a final rehearsal was held, and the assault elements of the battalion transferred to three tank landing ships, which carried the amtracs assigned to transport 1/27 to Red Beach 2.

On D-day, Feb. 19, 1945, the assault elements of 1/27, on the heels of the first wave of armored amtracs, began coming ashore at exactly 9:02 a.m. Landing on their left was 2/27 on Red 1, and on their right, 1/23 from 4thMarDiv on Yellow 1. 1/27, as the right-flank battalion of 5thMarDiv, was tasked with the D-day mission of securing the southern end of Motoyama Airfield just inland from Red Beach 2 and advancing on order to the 0-1 Line, drawn on a map, representing the final D-day objective. Their secondary mission was to maintain contact with the 4th Marine Division. The 28th Marines, landing on Green Beach, were tasked with cutting off the head of Iwo Jima, Mount Suribachi.

On the extreme right, landing on Blue Beach, the 25th Marines of 4thMarDiv were assigned to secure the high ground overlooking the landing beaches. Enfilade fire from the high ground on the right and plunging fire from Mount Suribachi on the left pummeled the landing beaches and follow-on reserve units as the assault battalions struggled up the sand-studded terraces to reach their objectives.

LtCol Butler, who had landed on Red 2 in the fourth wave, with his assault elements, established his initial command post on a sand-covered blockhouse that still housed enemy troops, some of whom were attempting to escape from the onrushing assault. Initially, resistance was light, but that soon changed.

General Kuribayashi’s gunners unleashed their mortars and artillery. Company B of 1/27 landed out of position and soon became disorganized and ridden with casualties. GySgt Basilone, who led the machine-gun platoon of Co C, wasted no time. He immediately took control of a lost machine-gun squad from Co B and directed them toward a blockhouse that was causing serious trouble. Private First Class Chuck Tatum described that action in his book “Red Blood, Black Sand.” This was the first of several heroic actions Basilone performed in those first hours ashore as the battalion fought to gain their objective. Two hours after landing, Basilone, one of the Marine Corps’ legendary fighters of World War II, lay bleeding and dying from multiple fragment wounds caused by mortars. For his actions on D-day, John Basilone was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

LtCol Butler, accompanied by his radio operator, moved up to the top of the airstrip for better observation. From there, he could clearly see the disorganization of Co B, so he directed Co A to replace them on the right.

Returning across the fire-swept area under observation of snipers in wrecked aircraft, he led Co A forward on a sweep that, along with Co C’s advance on the left, gained the southern end of Motoyama Airfield No. 1 by midafternoon.

Though the battalion was far short of its D-day objective, 1/27 was the only Marine unit to secure any part of Motoyama Airfield No. 1 by the end of D-day. Their first night on Iwo Jima was uneventful except for some infiltration attempts and intermittent enemy mortar fire. The enemy shifted their main fire to the now-crowded landing beaches, turning it into a junkyard of wrecked landing craft tanks and vehicles. D-day was costly, and on the morning of D+1, 1/27 was ordered into regimental reserve.

However, they did not rest but instead followed 3/27 in trace, mopping up bypassed positions as the drive for the O-1 Line continued. Despite its reserve position, 1/27 continued to suffer casualties from enemy mortar fire, snipers and firefights at bypassed positions. Despite sizeable gains by 3/27 and 4thMarDiv securing a good portion of the airstrip, the O-1 Line was still not reached by day’s end. That night the battalion established a defensive position in depth behind 3/27.

On D+2, the 27th Marines went into reserve as the 26th Marines made a passage of lines and continued the drive toward the O-1 Line just north of the airstrip. Meanwhile, the 28th Marines remained fully occupied with Mount Suribachi. However, by midafternoon, a gap between 5th and 4thMarDiv had developed, and 1/27 was directed to fill it. Moving into this gap, the battalion prepared hasty defensive positions before darkness set in. That night, Japanese aircraft, including kamikazes, launched an air raid against the fleet offshore. The attack sank the escort carrier Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) and heavily damaged the Saratoga (CV-3), taking her out of the war. At midnight, the Japanese conducted a ground counterattack, concentrated against 1/27.

The attack was stopped cold by the battalion’s 81 mm mortar platoon, interlocked machine guns, and on-call artillery from the 13th Marines. This was one of very few Japanese counterattacks during the entire campaign, and one can speculate it was planned to take advantage of the gap in the lines or the distraction of the off-shore air raids.

Daybreak on D+3 found 1/27 dug in across open ground. A cold rain added to the general misery of three days of combat. Once again, the 26th Marines affected a passage of lines and 1/27 reverted to division reserve and moved to an assembly area just northwest of Motoyama Airfield No. 1, where the Marines rested and replenished. For the first time in days, the exhausted 1/27 Marines changed socks, ate hot rations and wrote letters. They slept on the ground under ponchos or blankets. It was not an R&R center as the war thundered around them and patrols went out to hunt snipers and secure bypassed positions. No place on Iwo Jima was secure and comfortable, but for the Marines of 1/27, this was a break from the front lines.

On D+8, the 27th Marines were released from division reserve. 1/27 went into an assault along with 2/27 on the left and 3/27 on the right. The objective was Hill 362A and the ridge complex extending to the western beaches. These heavily fortified positions were the western anchor of Kuribayashi’s main defense line, and they chewed up 1/27 and its sister battalions. Two days of brutal combat gained a foothold but did not secure the objective. Fighting in this area was some of the most vicious of the Pacific war. Before the complex finally fell to the 28th Marines, who had rejoined the fight after resting from the capture of Suribachi, much Marine blood was shed.

2/28, commanded by LtCol Chandler Johnson, relieved 1/27 and passed through their lines to continue the attack on 362A and the adjoining ridges. In the next few days, 2/28 lost three of their six flag raisers and their battalion commander. 1/27 licked their wounds in division reserve but not for long. On D+13, March 4, 1/27 was attached to the 26th Marines and back in the attack on the right flank, adjacent to the 3rd Division zone of action just northeast of unfinished Motoyama Airfield No. 3. The battalion advanced in a column of companies along a narrow front led by Co C, which soon became casualty ridden. LtCol Butler replaced Co C with Co B, which managed to gain a difficult additional 100 yards against stiff resistance.

D+14, March 5, was a day of no offensive operations for the entire Amphibious Force, somewhat like a called time out to reorganize, rest and refit. The battalion was detached from the 26th Marines and directed to rejoin its parent regiment. As 1/27 moved to an assembly area just north of Road Junction 338, LtCol Butler asked for his jeep and driver so he could make a visit to the regimental supply dump and the 27th Marines command post. As the jeep passed through RJ 338, it was hit by a Japanese 47 mm round that had targeted the area. LtCol Butler was killed instantly. The runner and radio operator who were with him were wounded.

Word of LtCol Butler’s death swept through the battalion and was felt deeply by the men, who had appreciated his upfront leadership style and his honest personal care and respect for them, a sentiment often expressed in letters to his wife. In his last hastily penned letter from “Tojo’s Cave,” after the bloody fighting on 362A, he wrote of the men’s splendid courage. For his action on D-day and his leadership throughout the battle, he was awarded a Navy Cross.

Replacing LtCol Butler was LtCol Justin Duryea, the 27th Marines operations officer, who had been the interim commander at Pendleton in January 1944 before LtCol Butler arrived.

After a few more days in reserve, the battalion was back in the front-line action. On D+18, with Co C in the lead, Platoon Sergeant Joseph Julian became a one-man wrecking crew. Julian destroyed a number of Japanese positions in a series of furious assaults before he was mortally wounded. He was awarded a Medal of Honor posthumously.

That afternoon Duryea was severely wounded when his runner detonated a mine. The battalion command passed to Major William Tumbelston, the original battalion executive officer. With Tumbelston in command, the battalion continued in the attack for five days of hard-gained yards in the rocky terrain of northwest Iwo Jima until he also was badly wounded and evacuated on D+23. Command of the battalion then passed to Maj William Kennedy, who had been the operations officer for 3/27.

Killed in action on D+23 was First Lieutenant William Van Beest, who had taken command of Co C when the original company commander, Captain John Casey, was shot in the foot on D+1. Van Beest, who had been fighting since D-day, was a diligent and heroic company commander. He was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross.

On D+24, 1/27 advanced 350 yards to the top of a ridge from which they could see Iwo’s northern shore. The end was in sight. In fact this was the last day of fighting for the shot-up battalion that had lost three commanders and the majority of its original officers and NCOs. The ranks had become replacements and a few very exhausted originals who had somehow survived.

Ordered to a rear assembly area, the battalion reorganized into two companies (A and B) and a headquarters company. For Co B and Headquarters, there was no more fighting. Those assigned to Co A were detailed to a composite battalion formed from the remnants of 2nd and 3rd Bns, commanded by LtCol Donn Robertson, the original commander of 3/27 and the only original battalion commander in the 27th Marines still on his feet. This composite battalion, along with the 28th Marines and elements of the 26th Marines, fought in the Gorge, a brutal piece of ground that protected Kuribayashi’s headquarters. For his heroics during the fighting with the composite battalion, Private First Class Daniel Albaugh of Co A was the last of six 1/27 Marines posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

On D+31, Co A was released from the composite battalion and rejoined 1/27. After saying farewell to their buddies at rest in the large 5thMarDiv cemetery, the remnants of 1/27 boarded a troop transport and departed the island of Iwo Jima. In 29 days of brutal combat, including Co A’s six days with the composite battalion, 1/27 lost 233 KIA or DOW and 557 WIA, for a total of 790 casualties.

This was one of the highest for the 24 battalions which fought on Iwo Jima. Only 1/26, with a total of 1,025, and 2/25, with 804, had higher casualties. Among the officers, no battalion suffered more than 1/27, which lost 11 officers KIA or DOW and another 27 WIA. Among the entire battalion staff, including two surgeons, only the S-2 and the communications officer were unscathed. Only one of the three original line company commanders, Captain John Hogan in Co A, was not a casualty. Co C had no original officers left after the loss of 1stLt Van Beest on D+23. Among the 34 officers and NCOs listed as boat team leaders for each of the amtracs with the 1/27 assault element, 31 were killed or wounded.

1/27 lost the cream of its officers, NCOs and experienced men, yet continued to fight and carry out its mission until the bitter end. Like all the units of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Marine Divisions that fought on Iwo Jima, 1/27 established forever the legacy of Marine courage and “uncommon valor,” represented by the Marine Corps War Memorial. Its short and valiant history belongs alongside other storied Marine battalions which have so nobly served our Corps and nation.

Author’s bio: John A. Butler III was born July 30, 1939, in Quantico, Va. He enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve in 1957. He was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy that same year and upon graduation was commissioned a second lieutenant. He served on active duty from 1961-1966 as an infantry and counterintelligence/human source intelligence officer. He served in the reserve with the 4th Reconnaissance Battalion in San Antonio from 1966-1967 and worked in the maritime industry before retiring.