On Nov. 10 across the globe each year, Marines in every clime and place don dress blues with freshly mounted medals and slip on high-gloss Oxford shoes, or the spit-shined “Hershey’s,” to celebrate the Marine Corps Birthday. We listen intently to Major General John A. Lejeune’s message read aloud, feeling goosebumps as we listen to “The Marines’ Hymn.” We envision ourselves in a grand formation spanning the ages, surrounded by the historic pageantry of brother and sister Marines across 10 generations. This year, we celebrate a special milestone, the “Sestercentennial,” celebrating 250 years as the finest all-domain fighting force the planet has ever known.

To understand the context behind how we celebrate our birthday, Leatherneck recently explored the National Archives, Marine Corps History Division, the Library of Congress and other online repositories. Along the way, we discovered a cast of unsung trailblazers who tirelessly supported the Marine Corps’ most storied leaders in codifying what is today’s most coveted and time-honored tradition. Their contributions, preserved yet faded by time, shaped today’s celebrations through art, writings and recommendations. From the crimped and brittle materials emerged a passion for tradition still vibrant today. Their teamwork may have also proved crucial in helping leaders secure the Marine Corps’ existence.

Our modern celebrations were born out of uncertain times. One hundred years ago, as the Marine Corps approached its 150th birthday, postwar sentiments might have derailed the Corps from reaching that date. To reinstill public confidence, preserve our legacy and galvanize our place as America’s premier “force in readiness,” the Marine Corps had some work to do to avoid extinction.

Following the Great War, the “postwar disarmament period” found the Marine Corps struggling for existence. Downsizing shrank the Corps from a 75,101 peak end strength in 1918 to 27,400 by 1920, a nearly two-thirds diminishment in manpower. America wanted time to recover and to prosper in hard-won peace, having made the world safe for democracy.

An isolationist fervor emerged and dominated the political climate. In a speech, U.S. Senator Warren G. Harding asserted, “America’s present need is not heroics but healing; not nostrums but normalcy; not revolution but restoration; … not surgery but serenity.” His comments reflected common sentiments to leave international problems overseas for a return to domestic “normalcy.” Harding’s views would elevate him to such prominence that he secured his inauguration as President of the United States on March 4, 1921. Calls to broaden U.S. Navy downsizing added to the sentiment. On Nov. 12, 1921, Secretary of State Charles E. Hughes declared in front of an international audience in Washington, D.C., that the United States needed to limit naval capabilities, as should the other major world powers, including Great Britain and Japan. He proposed a 10-year shipbuilding holiday and 66 ships to be scrapped. Reports indicated that the attending audience responded with “wild applause,” indicating popular support for what represented large-scale disarmament. This led to deep budget cuts, military downsizing and a bureaucratic reset, echoing the challenges of our modern interwar period. Marine Corps senior leaders had a legitimate cause for concern.

Commandant Lejeune remained focused, driving what later became the Marine Corps’ “first enlightenment,” emphasizing unique expeditionary and amphibious capabilities. He knew that, to remain relevant, our Corps needed to change. He reorganized the headquarters, developed schools, instituted Advanced Base Force training, modernized equipment and built rapid-deployment amphibious capabilities. The Marine Corps already had a suitable place to train, educate, experiment and deploy expeditionary might, well proven during World War I. The Marine Barracks Quantico, Va., had emerged as a powerhouse for expeditionary deployment that MajGen Lejeune himself developed while serving as one of the first commanding generals.

Quantico’s real estate boasted capabilities for all warfighting domains, representative of the Marine Air-Ground Task Force. The base offered ample space to quarter troops, conduct artillery and infantry maneuvers and sustain troop transport by water and rail. Brown Field, now Officer Candidates School, teamed with biplane aircraft, undoubtedly frequented by the Corps’ first Marine aviator, Alfred A. Cunningham, the base assistant adjutant and inspector. The Quantico pier regularly docked Navy steam-powered ships for swift embarkation.

When MajGen Lejeune had been selected for his two-star grade and Commandant on July 1, 1920, he appointed his right-hand man, Brigadier General Smedley Butler, to succeed him. The insightful two-time Medal of Honor recipient continued the Commandant’s intent by further developing the base, expanding schools, training for Advanced Base Force operations and showcasing Marine expeditionary capabilities to the public. The base hosted a variety of public events, including football games at the new stadium (now Butler Stadium) to rally public support. Most visible to the public, Butler and his Marines conducted a series of marches to reenact battles at the Wilderness and Gettysburg, showcasing modern equipment and tactics. He and the Commandant hosted influential political leaders, including President Warren G. Harding and former Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels.

However, MajGen Lejeune needed to continue to develop ways to appeal to the public, while at the same time inculcating the shared pride that esprit de corps delivers. Documents show that Lejeune was keenly aware of the importance of public awareness through the media. Not only did celebrating the Marine Corps build a sense of institutional pride, esprit de corps and unity within, but the occasion could serve to garner public support as well. But there was a problem. Until 1921, the Marine Corps’ founding date was believed to be July 11, 1798, due to a law signed by President John Adams establishing the Marine Corps as an independent branch of military service.

Major Edwin North McClellan, a studious, prolific writer assigned to lead the Historical Section of Headquarters Marine Corps (HQMC), played a key role in the establishment of Nov. 10, 1775, as the Marine Corps’ birthdate.

Reviewing McClellan’s many writings showed variances in the Marine Corps’ exact origins, complicated by 11 state navies, including all but two of the original colonies, New Jersey and Delaware. He grappled with questions on when to draw the line on what constituted the original Marines. Evidence supported going as far back as the first British Royal Marines on American soil, state-appointed Marines or Marines who served on the first American warships to fight in the Revolutionary War aboard the sloop Liberty and the schooner Enterprise. He had to parse through a confusing start where the 1775 resolution created the Continental Marines, but they were disbanded after the Revolutionary War. The 1798 Act later reestablished the Marine Corps under the new U.S. Constitution, which led some to view that date as a new “founding” moment, until historical research prioritized the earlier date. McClellan settled on what came from the American people via the Second Continental Congress resolution signed on Nov. 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pa. Accordingly, he delivered his recommendations to the Commandant on Oct. 21, 1921, on what celebrations he thought most appropriate to mark the occasion each year. Maj McClellan’s work formed the genesis behind Marine Corps Order No. 47, Series 1921, read aloud today, signed by MajGen Lejeune on Nov. 1, 1921.

Despite all these efforts, critics continued to argue about the Marine Corps’ disbandment. One of these critics, Brockholst Livingston, a wealthy, influential New York resident, wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy on June 13, 1923, asserting that “a plan should be outlined in which the Marine Corps would be joined with the Line [Navy], doing away with Marines entirely.” He argued that retaining the Corps would be purely sentimental and less a matter of economy. Livingston proposed that most duties performed by Marines could be assumed by the Navy and that camps at Quantico and Parris Island, S.C., should be abandoned. He asserted that other capabilities could be absorbed by the Army, such as overseas garrisons in Peking, Haiti and Santo Domingo. He likened these changes to replacing horses with motor power, or sailing ships with electric drives, by “replacing obsolete organizations with modern ones.”

MajGen Lejeune, ever the consummate professional, replied to Livingston’s letter within six days, thanking him for furnishing him a copy and stating that his concerns would “receive due consideration.” He then drafted and delivered a memo to the Secretary of the Navy, pulling no punches between professionals. He posited that Livingston’s arguments were a “fallacy,” arguing that Marines had been employed aboard naval vessels since the earliest times. Commandant Lejeune went on to argue they should be retained, that the Navy did not train Sailors to operate ashore and that the Army did not have “sufficient numbers in times of emergency” nor the proper training or organization to operate promptly and in harmony with Naval forces. In his final argument, Lejeune declared that Marines “are abreast of the times in the use of modern methods which they employ in their operations,” and that “they are as modern and up to date as any troops or any body of armed men in any country in the world.”

As the Marine Corps continued the fight to exist, the 150th anniversary rapidly approached. The Corps’ birthplace in Philadelphia, Pa., emerged as a natural choice to celebrate the occasion. However, in the early 1920s, the city was hardly a place to support parades and ceremonial events or play host to dignitaries. The crime rate had escalated. Bootlegging and police corruption ravaged the city and threatened peace and public safety. So, the city mayor, W. Freeland Kendrick, frustrated with police union influences and corruption, turned to his friend BGen Smedley Butler for help. He petitioned President Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding following his death, to select Butler to take charge as the city’s director of public safety, and, in an unprecedented peacetime measure, Coolidge granted his request. In December 1923, Commandant Lejeune relieved BGen Butler of his Marine Expeditionary Forces, U.S. Fleet command. The Commandant granted him one year’s leave from the Marine Corps to assume his civilian duties, and in the process, he set the stage for a city-wide crime-fighting field day to enable preparations for Sesquicentennial events.

Immediately following his oath in January, Butler swapped his Marine Corps uniform for a police uniform and began work in earnest, summoning police leadership, captains and lieutenants and directing them to clean up the city within 48 hours or he would replace them with Marines. He moved a cot into his headquarters, disbanded the police union and initiated what resulted in a mass exodus of criminals from Philadelphia. Adjacent cities, including New York, reportedly set up barriers to keep “the undesirables from coming within their gates.” Crime rates went down. Of the 1,200 saloons raided by Philadelphia police under Butler, 973 were closed for illegal bootlegging. Butler served two years at the post, extending his second year by request. In his final year, having set the conditions for safe celebrations, he hosted the Commandant and numerous dignitaries in what became the first major Marine Corps Birthday celebration of its kind.

As the Marine Corps Birthday Sesquicentennial approached, planning began in earnest. David D. Porter, a Brevet Medal and Medal of Honor recipient, Commanding Officer of the Marine Corps Eastern Recruiting Division Headquarters in Philadelphia, submitted recommendations to MajGen Lejeune on how to celebrate the occasion appropriately. In his Feb. 27, 1925, letter, he credited an enlisted Marine, Quartermaster Sergeant Victor H. Rogers, with the following eight recommendations, listed verbatim:

“That a short history of the Corps be written and that same be read to all commands on that day.

That all ships be ‘dressed’ with flags, etc., on which Marines are stationed.

That a holiday be declared at all posts, etc.

That special athletic events be held.

That a dance or other suitable entertainment be held in the evening.

That a special dinner be served, the same as on Christ-mas, etc.

That a special story be written by the Recruiting Bureau and distributed to the newspapers, together with appropriate pictures.

That the Recruiting Bureau issue an appropriate poster for display on ‘A’ signs.”

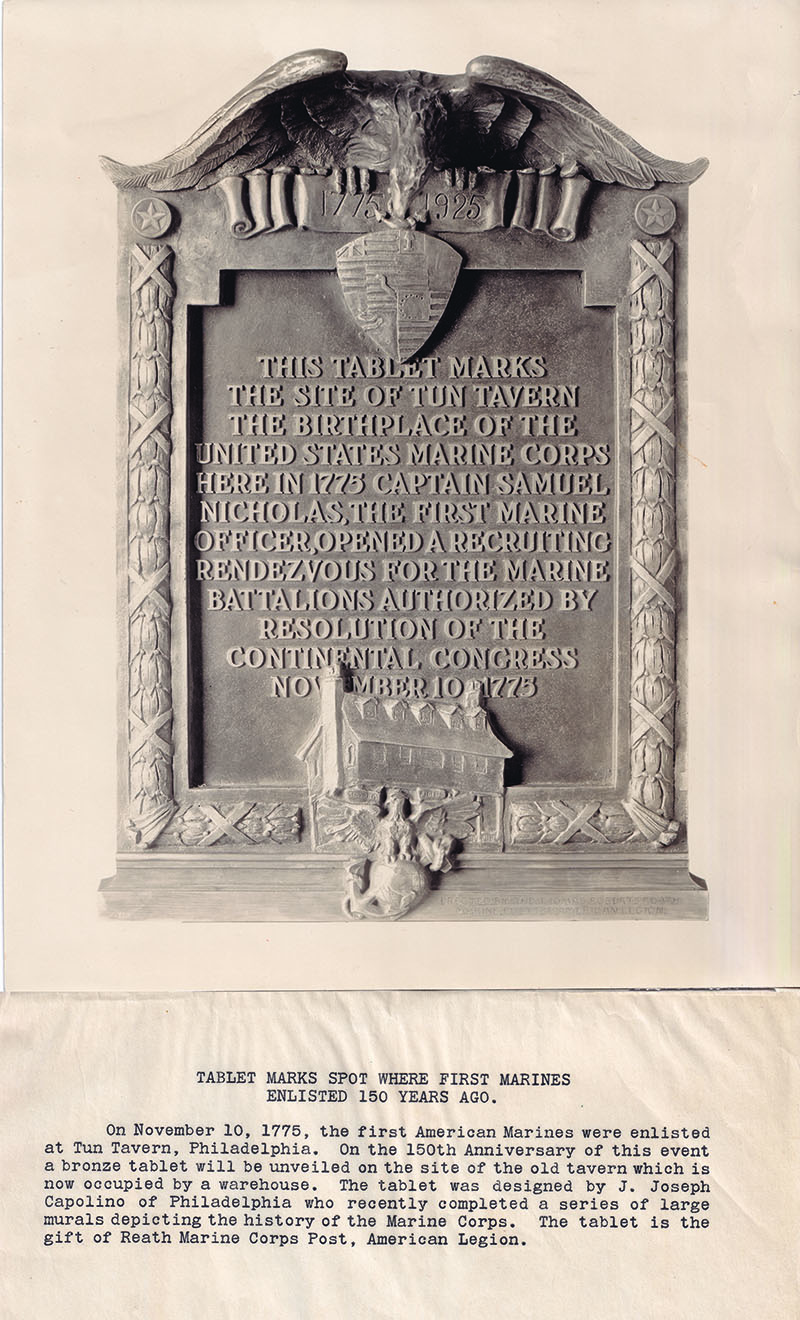

Philadelphia’s Thomas Roberts Reath Marine American Legion Post No. 186 sponsored the venue with the active co-operation of the mayor of the city of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. Their membership boasted the only chapter that consisted solely of Marine Corps veterans nationwide. The sequence of events would begin on Nov. 10, 1925, with a bronze tablet dedicated at Tun Tavern’s original site, followed by a parade in the afternoon, then a birthday party celebration and dinner conducted at the Ben Franklin Hotel, to be followed that evening with a separate “Military and Naval Ball” sponsored by the Marine Post at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel. More than 1,200 people would be invited to the dinner and 2,500 to the ball that would follow. This is widely accepted today as the “first” formal Marine Corps Birthday Ball.

Preparation took months leading up to the events. National Archives documents support that invitation letters went out to 56 military, civilian and local dignitaries, including 15 state governors, 16 senators and 20 representatives responsible for Naval affairs. Many written replies expressed sincere regret due to scheduling conflicts with Armistice Day celebrations the following day and other events. An HQMC memo showed pencil annotations next to the names of eleven field- and company-grade staff officers who could not attend. This initial celebration would be optional for Marine Corps attendees. However, formal tasks went out from HQMC for troop support from all East Coast Marine Corps installations, including Quantico, the Navy Yard, Philadelphia and the Eastern Recruiting Division.

To kick off the first event, the distinguished guest entourage presented the bronze tablet at Tun Tavern’s original site. One of the first artists commissioned by the Marine Corps, John Joseph Capolino, created the token. He also is credited with producing a series of large murals depicting the Corps’ early history, hung in the first Tun Tavern replica built the following year for the Sesquicentennial Exposition of 1926. Today, copies of the prints line the third-floor walls of the U.S. Marine Corps History Division, Marine Corps University, in Warner Hall. The original tablet is no longer at the site in Philadelphia and resides today at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, though not on display. The artifact is now covered in patina and aged greenish with corrosion but still bears the legible inscription.

After the tablet dedication ceremony, a parade immediately followed. The parade featured a special float containing a birthday cake with 150 candles at the top, along with 13 American flags. Four Marines accompanied the cake, dressed in period and colonial uniforms. The traditional eagle, globe and anchor depicted the fouled anchor opposite in appearance today, with the anchor oriented diagonally behind the globe from left to right.

Following the parade, Marine senior leadership, dignitaries, Marines and their guests headed to the Ben Franklin Hotel for the banquet. Later that evening, the culminating event at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel followed. Newspaper clippings out of the National Archives, Smedley Butler and John A. Lejeune collections, show that the event was broadly circulated in print and well attended. The Evening Star, a Washington, D.C., newspaper, reported that Secretary Wilbur declared during the banquet, “The accomplishments of the United States Marine Corps from the day of its foundation, November 10, 1775, to the present time have more than fully justified the wisdom of its establishment.” The event succeeded in capturing the attention, the imagination and the appreciation of a grateful nation. In essence, the entire team of Marines, active, on leave and veteran, coalesced together not only to reignite our heritage but to rekindle America’s love for her Marines. Indeed, these original celebrations not only delivered the Marine Corps’ case for preservation but ignited a torch of tradition that we bear in ceremony to this day. Standing on the shoulders of our ancestral teammates, we bear the same responsibility to preserve our storied legacy as we celebrate our 250th year.

The words below from MajGen John A. Lejeune to President Calvin Coolidge to commemorate the 150th in 1925 ring as true today for the Sestercentennial as they did back then:

“Marines have therefore traditions to uphold, traditions of loyalty, well exemplified not only by our motto, ‘Semper Fidelis,’ but by the heroism of our predecessors,” Lejeune wrote in the Oct. 21, 1925, memorandum. “Our country is now at peace, but we have still the obligation faithfully to carry out the duties assigned us and keep ourselves in readiness should our nation again be engaged in war, to defend her as of old.”

Featured Image (Top): A Marine Corps Birthday cake, surrounded by Marines dressed in uniforms representing leathernecks of the past, sits atop a drivable float that was used in a parade in Philadelphia, Pa., to celebrate the Marine Corps’ 150th Birthday, Nov. 10, 1925.

Authors’ bios: LtCol Brad Anderson, USMC (Ret), is a freelance writer and researcher for Leatherneck.

Katie Cashwell is a veteran Marine. She is a graduate of the Uni-versity of Mary Washington with a degree in historic pres-ervation. She has spent decades providing research supporting recoveries of America’s Missing in Action. She was instrumental in researching the lost graves of Tarawa.