A row of MAG 26 A-4 Skyhawks line up at Guantanamo Bay Naval Station during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Multiple aerial surveillance missions were conducted to monitor Cuban military activity. (DOD photo)The path to a first direct military confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union became possible when Fidel Castro’s communist revolution toppled Cuban President Fulgencio Batista on Jan. 1, 1959.

At the center of President John F. Kennedy’s joint U.S. military invasion plan to remove Castro from power and block the Soviet military buildup in Cuba was the U.S. Marine Corps. Documents declassified over the last decade, along with firsthand accounts, provide fascinating, previously unknown details of the Marine Corps’ role in planning and the II Marine Expeditionary Force’s (II MEF) part in executing the invasion that never was.

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara; Gen David M. Shoup, the 22nd Commandant of the Marine Corps; and President Kennedy observe an amphibious landing demonstration conducted by the II Marine Expeditionary Force at Camp Lejeune, April 17, 1962. (Photo courtesy of John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

The Cold War Heats Up

A New Year’s Day parade in Havana on Jan. 1, 1962, provided the world with the first tangible proof of just how far Cuba’s military relationship with the Soviet Union had come. According to the U.S. Atlantic Command’s “Historical Account of the Cuban Crisis,” on parade that day were 60 modern Soviet-made fighter/attack aircraft, light cargo transports, and helicopters as well as thousands of uniformed and well-equipped Cuban infantry followed by artillery pieces, tanks, and an array of armored vehicles. Reports estimated that Castro’s conventional ground forces ranged from 75,000 to 100,000 soldiers, a far cry from the 300 or so that had overthrown Batista three years earlier. The Joint Chiefs asked Admiral Robert L. Dennison to keep Cuban invasion planning the U.S. Atlantic Command’s highest priority. Dennison in turn directed his planners to amend its active Cuban invasion plan, OPLAN 314-61, to reflect the realities of this new Cuban army.

Throughout early 1962, Dennison had planners draft two new courses of action. One, OPLAN 316-61, was a “quick reaction” version of OPLAN 314-61 and provided only five days of preparations (including airstrikes) before the airborne assault, with amphibious assaults occurring three days or less thereafter. The second plan, OPLAN 312-62, was an air strike-only option with the II MEF reinforcing and expanding the Guantanamo perimeter.

With the invasion becoming less likely despite disconcerting intelligence reports, President Kennedy communicated his resolve through American TV and newspapers. What were normally routine training exercises received national media attention. On April 17, Kennedy and several senior cabinet and Department of Defense officials traveled to Camp Lejeune, N.C., to observe one of several II MEF amphibious exercises taking place along the Atlantic seaboard that spring. On hand were Marine Corps Commandant General David M. Shoup, ADM Dennison and his staff, and the II MEF’s new commanding general, Lieutenant General Robert B. Luckey. Lance Corporal Stanley E. Gunn from 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines recalled the exercise: “It’s not every day that you get to train in front of the president, so a lot of us thought Kennedy’s visit was more than to observe an amphibious landing exercise. It was a final rehearsal.”

Fidel Castro and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev received Kennedy’s message. The Central Intelligence Agency’s September 1962 report “The Military Buildup in Cuba” linked a Soviet cargo ship surge in Cuba in August (55 dockings) and September (66 dockings) to a plan to rapidly “strengthen Cuban defenses against air attack and seaborne invasion.” Delivered to Cuban ports were Soviet-manned SA-2 guided surface-to-air missiles, Soviet-made Badger medium-range bombers, and Komar guided-missile patrol boats, all a clear indication that Castro believed an amphibious assault was imminent. In addition, the CIA estimated as many as 20,000 Soviet military personnel were on the island as stand-ins until trained Cubans could replace them. Most alarming was the CIA’s warning of the potential for Khrushchev to deploy an army group and offensive and nuclear strike capabilities (air, surface, and submarine) to Cuba, though the latter was a significant departure from Soviet policy.

Within weeks of Kennedy stepping up aerial surveillance missions over Cuba, an American U-2 reconnaissance aircraft produced “hard photographic evidence … that the Russians [had] offensive missiles in Cuba.” Kennedy wanted confirmation before taking any action. The Joint Chiefs and ADM Dennison tasked the Navy and Marine Corps with providing that confirmation. On Oct. 17, Marine RF-8A Crusader crews from 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing’s Marine Composite Reconnaissance Squadron 2 endured Cuban ground fire during dozens of photographic missions flown as low as 50 feet above the jungle landscape. “We would go around the island and triangulate to find the radar sites,” retired Lieutenant Colonel Richard Conway explained years later. “We sent that back to Washington, so when they planned our targets, they knew where the sites were. They could direct us over one, over another and another in a straight line because we had located those sites for them.”

President Kennedy met with his national security team and the Joint Chiefs to review the photographs and weigh his options. The military leadership agreed unanimously to air strikes aimed at destroying only the sites. A ground invasion, they offered, would be needed to seize the missiles intact. The objective would then shift to defeating Soviet and Cuban forces and removing Castro from power.

Atlantic Command planners revised OPLAN 314-61 and OPLAN 316-61 to reflect the priorities and objectives. Meanwhile, President Kennedy delayed offensive military action for at least 90 days to give diplomacy a chance, but adopted from OPLAN 314-61 the naval quarantine course of action in conjunction with posturing the invasion force to act on a moment’s notice. To do this, the Joint Chiefs directed ADM Dennison in an Oct. 26 memorandum to “abandon OPLAN 314 and concentrate on OPLAN 316-62.”

An aerial view of the MRBM Field Launch Site in San Cristobal, Cuba, photographed Oct. 14, 1962. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

Operation Scabbards

While the diplomatic process played out, invasion forces entered quietly into Phase I of OPLAN 316-62. As a testament to the former II MEF commander’s forward thinking, more than 4,000 Marines of the 4th Marine Amphibious Brigade (MAB) were already in the Caribbean preparing for Exercise Ortsac (Castro spelled backward), scheduled months earlier for the period of Oct. 15-30. The DOD secretly suspended the exercise on Oct. 20 but used it and the fast-approaching Hurricane Ella as a cover for moving ships and aircraft out to sea and to Caribbean bases.

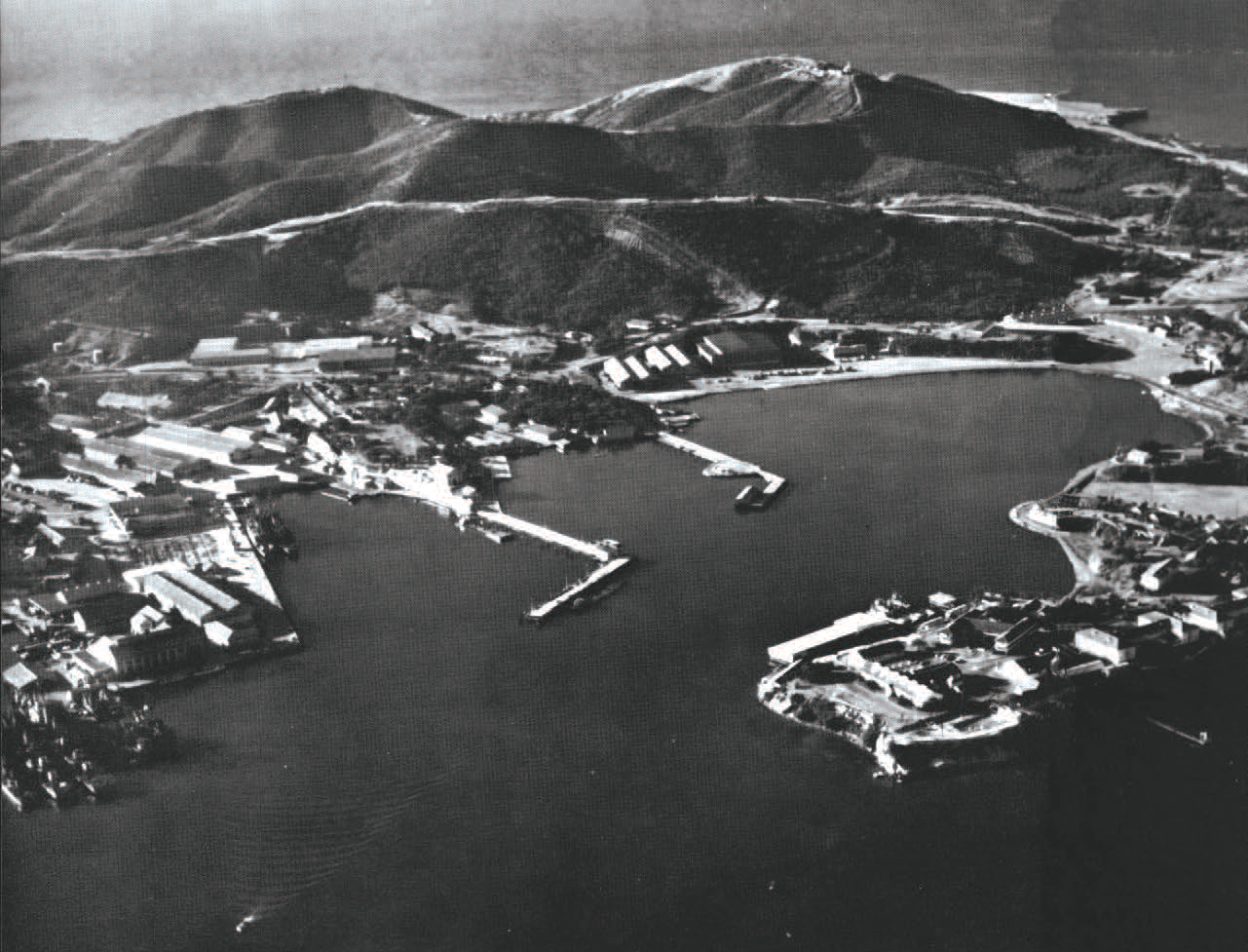

LtGen Luckey activated the II Marine Expeditionary Force officially on October 23. In his role as Fleet Marine Force, Atlantic (FMFLant) commanding general, he requested on Oct. 19 that ADM Dennison land 2/2 (already in the Caribbean) at Guantanamo Bay and ordered Major General Frederick L. Wieseman to have one of his 2nd Marine Division battalions reinforce them as planned and begin moving his units to their embarkation points. Two days later 1st Battalion, 8th Marines joined 2/2 in Cuba as the core of Brigadier General William R. Collins’ Marine Ground Force Guantanamo. The situation caught many Marines by surprise. “We were in Vieques and we started training to invade Cuba but we didn’t know it,” recalled 2/2’s LCpl Ralph E. Johnson. “They told us to go down to Red Beach and a ship would pick us up. We got on board and they said we were headed to Cuba.”

BGen Collins’ aerial reconnaissance of Guantanamo Bay resulted in a request for a third battalion. With the only available units embarking ships, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps (HQMC) tasked Fleet Marine Force, Pacific (FMFPac) with providing the battalion. The 1st Marine Division’s 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines flew from Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in California late on Oct. 21. The battalion was in fighting positions and running patrols the next day. They were not the only unit from FMFPac to receive deployment orders.

BGen William R. Collins (pictured as major general), Commanding Officer, Marine Ground Force, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Courtesy of Marine Corps History Division.

BGen William T. Fairbourn, (pictured as major general) Commanding General, 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade. (USMC photo)During planning in July 1961, 2ndMarDiv staff raised concerns over conducting “assault landing operations” so soon after seizing Tarara. HQMC agreed and directed FMFPac to create a brigade for the invasion. Given the Cuban Army’s increased capabilities and the potential for direct Soviet military involvement, LtGen Luckey requested on Oct. 23 that BGen William T. Fairbourn’s 5th Marine Amphibious Brigade (MAB) be activated and assigned as Landing Group East and the II MEF’s reserve. FMFPac received the activation message that same day. The entire brigade had to be embarked within 96 hours. Four days later the 9,000 Marine air-ground force departed southern California on board 20 amphibious ships, including the Navy’s newest purpose-built amphibious assault carrier USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2). Embarked were 1st Marines and its two remaining battalions; 1st and 3rd Battalions, 7th Marines; Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 361; and a logistics support group. Marine Aircraft Squadron 121 and Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 352, with 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Missile Battalion on board, flew ahead of the ships to assume firing positions at Key West, Florida, and Guantanamo Bay naval stations.

The brigade’s only stop was a brief one inside the Panama Canal, where BGen Fairbourn noted, in an interview years later, that his Marines “loaded blood and a hundred coffins onto the carrier Iwo Jima dockside in Panama” in hopes that there was an audience watching. “And then we sailed.” Private First Class Thad McManus of 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, on board USS Okanogan (APA-220), remembered how loading the coffins “was supposed to impress the Soviets.” The ploy, however, “sure impressed us.” Just before departing, Fairbourn received a naval message with orders “to land on the coast of Cuba, seize Santiago, and march on Havana.”

Gen Shoup speaks with a Marine from 2/1 in defensive positions at Guantanamo Naval Base. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

PFCs Robert Broughton and Mimmy R. Isabell of 1/8 set their 81 mm mortar on enemy positions along the Main Line of Resistance. (Photo courtesy of Marine Corps History Division)

A Marine from 2/2 watches over the approaches to Guantanamo Naval Base during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Courtesy of National Archives.With more than 38,000 Marines “mounting out,” LtGen Luckey faced the unenviable challenge of commanding and controlling from Norfolk a force scattered throughout the Atlantic and Caribbean. To take advantage of the communications infrastructure, Luckey and the II Marine Expeditionary Force command element operated from FMFLant command center. There, Luckey and his staff would synchronize air and ground actions by units embarked on two amphibious task forces spread over 58 ships and four bases. The challenge was not lost on even the most junior Marines. “I know that the high ranks thought it was a complete (mess) logistically, command scattered all over the fleet, plans being re-done all the time, but that was way above me,” PFC McManus recalled.

MajGen Wieseman’s staff had the arduous process of organizing 2ndMarDiv, the bulk of Landing Group West, into assault elements. Spread out over 40 ships were 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines and 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines with attached artillery batteries from 10th Marines, engineers from 2nd Pioneer Battalion, tanks from 2nd Battalion, and amphibious tractors from 2nd Amphibian Assault Battalion, all of the battalions and combat support attachments of 6th Marines, and 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines and 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines, reinforced by combat support attachments. His 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing counterpart, MajGen Richard C. Mangrum, faced a similar test in commanding and controlling Marine Aircraft Groups 14, 24, 26, 31, and 32 and several independent combat aviation and support squadrons operating from aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, and the Cecil Field, Key West, Roosevelt Roads, and Guantanamo Bay airfields.

MajGen Richard C. Mangrum, (pictured as lieutenant general) Commanding General, 2nd Marine Air Wing, 1961-1963. (USMC photo)

LCpl Ralph Maynard and Cpl James K. Campbell from 1/8 defend the Main Line of Resistance, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Courtesy of Marine Corps History Division.

Standing Down

After 13 days of tense negotiations that kept the world on the brink of nuclear war, the crisis subsided when President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev reached an agreement on Oct. 28. In exchange for Khrushchev removing all Soviet nuclear and non-nuclear offensive capabilities from Cuba, Kennedy promised to remove all American nuclear missiles from Turkey at a future date. Had the invasion occurred, the II MEF would certainly have landed at Tarara to establish the beachhead for 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions to pass through.

Naval aviators CDR William Ecker, left, and Capt John Hudson, right, shake hands, after President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev reached an agreement on Oct. 28, 1962. (Photo courtesy of Michael Dobbs)

Soviet freighter Kasimov withdraws from Cuba carrying 15 IL-28 “Beagle” bombers on deck. (Photo courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command)Planners changed the 1st Armored Division’s land site back to Regla, inside the Port of Havana, after 2ndMarDiv handed off Tarara, attacked west to clear the northern coast, secured the Morro Castle at the entrance of the Port of Havana, and secured Regla. In the event of a delay, the armor landing site was to shift farther west to the Port of Mariel. According to Atlantic Command’s 1963 historical account, estimated casualties in the 260,000 American invasion force (150,000 ground forces) were 18,484 killed, 8,182 of those coming from the II MEF with 4,462 on the first day alone. Planners estimated 800,000 Cuban servicemen and civilians would perish during the anticipated 15 days of combat operations.

Within days of Kennedy and Khrushchev’s agreement the II MEF stood down incrementally. Most of its units were back at their bases by Christmas. The 5th MAB was back in California by Dec. 10, including 2/1. BGen Fairbourn disbanded the brigade but kept his staff together to finalize plans reflecting the Atlantic Command’s updated invasion schemes following OPLAN 316-63’s approval by the Joint Chiefs in early January 1963 and the II MEF’s updated component plan. In the event Khrushchev did not comply, the brigade made plans for assault landings at Matanzas and Mariel and to retake Guantanamo Bay or Santiago de Cuba, if necessary.

The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines remained afloat in the Caribbean for another two months as part of a multinational observation force. “I was on the deck of the Okinawa when we saw the Russian ships leaving Cuba,” PFC Robert P. Hemingway recalled decades later. “The missiles were plainly visible with binoculars on the decks of the Russian ships.”

To maintain their readiness, all units took advantage of training opportunities at Guantanamo Bay and Vieques, including those awaiting orders to redeploy to Camp Lejeune.

Then-1stLt William M. Keys with his platoon sergeant on board USS Boxer (CV-21) during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Keys was aboard an OH-43D Huskie helicopter that crashed at sea in early December 1962. (Photo courtesy of LtGen William M. Keys, USMC (Ret))During an exercise in early December, a Kaman OH-43D Huskie helicopter from Marine Observation Squadron One crashed into the Atlantic Ocean forward of USS Boxer (CV-21) during a fire support training exercise. On board the two-man aircraft was First Lieutenant William M. Keys, who, as a platoon commander in 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, was on a temporary assignment to the squadron as an aerial observer. Knocked out upon impacting the water, 1stLt Keys regained consciousness just as Boxer ran directly over top of the wreckage with him trapped inside. “I somehow kept my composure and focus, freed myself, and swam to the surface where a rescue helicopter pulled me out of the water,” Keys explained. His commanding officer, LtCol Earl W. Cassidy, attributed Keys’ “physical condition and presence of mind” to his surviving the crash. Some 20 years later MajGen Keys would lead 2ndMarDiv in liberating Kuwait from Iraqi occupation in February 1991 and, later, command both the II MEF and FMFLant as a lieutenant general from 1991 to 1994. (Editor’s note: The article “Genesis of the Second Breach,” from the August 2022 issue explains more about Keys’ role during Operation Desert Storm.)

The magnitude of the crisis surprised many. “No one knew they had nukes down there. We were aware they had missile sites that put Washington, D.C., and a few other places in range,” retired Col Edward Love said long afterward. President Kennedy presented the Distinguished Flying Cross to Love and fellow Marine aviators Fred Carolan, Richard Conway, and John I. Hudson, who retired as a lieutenant general, for their heroic actions over Cuba. Some were shocked the invasion never materialized. Cpl Robert Thomas of 2nd MarDiv’s 2nd Pioneer Battalion recalled, “I thought we were going to war. It got serious for us when we started firing machine guns off the stern of the ship. We thought something might come out of it.”

Still others were just happy to play a part. “Sitting there watching the TV, you feel really proud about what you contributed,” LtCol Conway added years later. “It was a very rewarding experience.” Few were more pleased than Gen Shoup. “I couldn’t be happier about our readiness in this crisis,” he explained. “This time we not only have been ready, we’ve been steady.”

View of the wreckage of the VMO-1 OH-43D Huskie spotter helicopter that crashed into the water during the approach to USS Boxer (CV-21) in December 1962. (Photo courtesy of Lt Gen William M. Keys, USMC (Ret))

A sideview of USS Boxer (CV-21), refueling in Cuba, 1964. (USMC photo)Author’s bio: Dr. Nevgloski is the former director of the Marine Corps History Division. Before becoming the Marine Corps’ history chief in 2019, he was the History Division’s Edwin N. McClellan Research Fellow from 2017 to 2019, and a U.S. Marine from 1989 to 2017.