Patrolling Hill 55: Hard Lessons in Retrospect

By: LtCol Howard Christy, USMC (Ret)Posted on July 15,2025

Article Date 01/08/2025

A company grade officer’s memoir of duty in Vietnam and his reflections on how the Corps adjusted and responded to battlefield challenges quite different from those for which it was specifically organized and trained.

>Originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette, April 1994. Editor’s Note: The authors biography is available in the original edition.

We are taught by the book. That is, we are taught the basics of individual and unit discipline and movement under combat conditions. But some have said that we do this so that when the balloon goes up and the lead begins to fly we can throw out the book and play it by ear—but in a disciplined sense, a sense shaped and tempered by all that book learning and training. In Vietnam perhaps we ran across all too many occasions to throw out the book and play it by ear. We were, at least in the beginning, in a new kind of war for us, one for which the book had not been definitively written. But I wonder if we were wise to have thrown the book out with such regularity. On the other hand, I wonder if we had the flexibility—the professional sharpness—to reassess our course against what turned out to be an extremely resourceful enemy.

This article deals with some of the foolishness and perhaps the lack of flexibility that occurred in I Corps during the early part of the Vietnam War, and suggests lessons learned that may still have some application today. I was a first-hand participant in the events described, as the combat intelligence officer/briefer in the 3d Marine Division intelligence staff, and later as the commander of Company A, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines. However, in order to reduce personal references as much as possible, I use third-person (e.g., “the company commander” and “the company”) throughout. The perspective and conclusions presented are the result of considerable reflection over time; by no means was the apparent interrelatedness of events clear at the time. That might be a lesson in itself.

By the spring of 1966, combat elements of the 3d Marine Division seemed to be carrying out two strategies at the same time: the strategy of counterinsurgency that had been developed recently by American forces in collaboration with the guerrilla-savvy British and French, and a hybrid offensive strategy featuring scattered deployment and saturation patrolling coordinated with elaborately plotted “H & I” (harassing and interdiction) artillery fires. This more offensive strategy received the most emphasis, understandably so since it was more familiar than the land-control, pacification-oriented strategy of counterinsurgency, which in a three-pronged approach employed population control and assistance simultaneously and equally with the more combative counterguerrilla effort. Perhaps saturation patrolling and H & I fires were emphasized also because the first major Marine effort of the war—Operation STARLIGHT in the Chu Lai tactical area of responsibility (TAOR) during the summer of 1965—had been a conventional offensive operation against Viet Cong (VC) forces that stayed to fight instead of employing the more elusive strategy they emphasized later, particularly in the Da Nang TAOR. That is, perhaps the patrolling and H & I strategy was employed in the anticipation that we would regularly meet or “catch out” larger, more-fixed enemy units like those encountered in STARLIGHT. Did our approach work? That is, did it allow us to accomplish our objective?

Whatever may have been the merits of either strategy, it was obvious that the VC were not fools; in fact, they seemed to be quite capable of keeping us at bay while they seemingly moved at will. We knew that the VC were intently and shrewdly watching us. Stories of sand-table mockups of Marine positions painstakingly fashioned by the VC began to be reported by intelligence sources and were also reflected in captured documents, which included precise sketches of our positions. To us, this indicated an impressive knowledge of our overall order of battle. It was soon obvious that the VC had both the means and the moxie to make mines and booby traps out of just about anything that could be induced to explode.

These and other capabilities were determinable very early in the war. Three stark events in the summer and fall of 1965 if examined together could have given a clue not only of particular tactical capabilities but perhaps something more ominous. In September, one of the battalions of the 9th Marines set up a command post on Hill 55, southwest of Da Nang, and began patrolling in the sector surrounding the hill. One morning—just before the daily 8 a.m. briefing of the division commander was to take place up in Da Nang—the battalion commander, during a short reconnaissance near the north slope of the hill, tripped a booby-trapped 155mm artillery shell that exploded with a roar and blew the colonel to pieces. The tragedy was immediately reported to division, and the intelligence desk officer ran the grim information over to the conference room just as the G-1 portion of the briefing commenced. The G-2 briefer hastily noted the information and silently slipped it to the commanding general immediately before taking his turn on the platform. The general was visibly shaken by the report. He read the note silently, then handed it to the officer beside him and bowed his head. There was utter silence in the room as the note moved up and down the table, then the general grimly nodded for the briefing to continue. Following that incident the division intelligence staff began a careful study of the incidence of mines and booby traps, and information on that aspect of the war became a priority feature in future intelligence briefings.

About a week later, a VC force of estimated battalion size snuck up on and assaulted the Marine company occupying a remote outpost on Hill 22, on the division’s defensive salient northwest of Hill 55. The VC penetrated the perimeter and got all the way to the command bunker before the Marines were able to beat back the attack in desperate hand-to-hand fighting. Later, it was reported that the VC had made an elaborately detailed sand-table mockup of the outpost, then had shrewdly attacked at about 0245 when they knew the Marines were least likely to be fully alert. Though repulsed, they came precariously close to overrunning the outpost. The episode sent a shock through the division.

A few days later, the VC ingeniously employed a mine ambush; that is, they wired together several mines in an elongated “L” shape, sat in wait, then simultaneously exploded all the mines—probably with a hand-operated electric detonator—when a Marine patrol walked into their trap. The ambush was quickly investigated and briefed, and once again a shock went through the division staff.

If nothing else, these incidents pointed to the fact that we were up against a smart, as well as vicious enemy. But had we been alert enough to see it, they also clearly indicated that the VC had developed a strategy of their own, one designed precisely to counter our scattered deployment and aggressive tendencies. “Strategy” is the “science and art of military command exercised to meet the enemy in combat under advantageous conditions.” Could these seemingly unprofessional VC commanders have developed such a “science and art”? Could they have assembled a “book” on our tendency to dash aggressively about the countryside in small units aching for a fight? It seems in retrospect that they had. Sad to say, however, the matter never came up for discussion at division intelligence, and over the next several months, Marines kept to their strategy even though they seldom if ever had a significant meeting engagement with a sizable VC force. While at the same time, fully 90 percent of our casualties were being caused by mines, booby traps, and ambushes.

Early in the spring of 1966, a platoon on patrol north of Hill 55 walked into a massive ambush and was annihilated with the exception of two wounded Marines who survived the slaughter by feigning death as the VC poked about among the bodies collecting weapons and ammunition. Investigation revealed that the platoon, by repeatedly patrolling over the same ground, had established a pattern that the watchful VC had been able to spot and for which they prepared a devastating response. By now it should have been painfully obvious that the enemy was employing effective countermeasures and that the aggressive patrolling strategy needed to be reassessed in that light.

In particular, the aggressive part needed to be rethought. Far too many officers were inclined to aggressively maneuver against every known enemy sighting. Even the commanding general had demanded that his intelligence briefings include reports of every contact with the VC, including, in his exact words, “one-shot misses.” Demanding exacting information about the enemy is one thing; blindly chasing after shadows is another. An aggressive strategy is one thing; an overly aggressive strategy under the conditions we experienced is another. In the case of I Corps in 1966, a one-shot miss, or even a fusillade from a tree line, should not have necessarily demanded an immediate frontal assault, especially in light of the knowledge that the enemy was taking advantage of such a proclivity. In conversations between officers, aggressiveness was often the topic of discussion. Not unlike Custer, some seemed to think that it was up to them to end the war then and there, and with dash and flair. In one conversation with a battalion commander the question was put: If a unit was to draw fire from the far side of a wet rice paddy, would he order an assault across the paddy? Without hesitation he said that he would. Not often discussed was individual and unit security, particularly individual dispersion and unit point and flank security. Although such basic concerns may have been taken for granted, failure of senior commanders to continually warn of the crucial nature of unit security in a strategy emphasizing constant aggressive movement was extremely shortsighted. These aspects of the early war—the strategy of saturation patrolling; the counterstrategy of mines, booby traps, and ambushes; the tendency to be overly aggressive; and underemphasis on individual and unit security—were sure to lead to trouble, and the Marines in I Corps continually walked into that trouble.

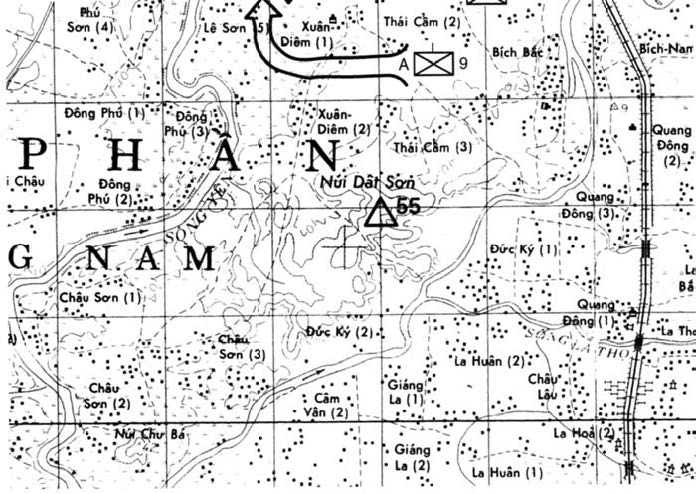

On 21 May 1966 several weeks after the above-mentioned ambush, another company was assigned to carry out a County Fair counterinsurgency operation at the little village of Thai Cam (2) also in the area north of Hill 55. The counterguerrilla aspect of the operation went off without incident, and by noon the troops had little or nothing to do as the attached medical and other relief and assistance people did their work. But gunfire began to crackle off to the west, and the company saddled up for possible action in that direction. Minutes later the battalion commander, who was located at his command post on Hill 55, radioed for a platoon to be detached and flown by helicopter to join the adjacent company, which had become engaged by fire with an enemy force across the river that marked the boundary between the two companies.

Now at least some of the company were perhaps going to have a taste of real war, the old-fashioned kind with which we were the most familiar. Two large cargo helicopters flew in and picked up the 3d Platoon (with a section of machineguns attached), and within the hour the entire company was ordered to move directly to the scene of the battle and engage the enemy in support of the other company. The troops climbed onto the two battle tanks and two amphibious tractors at hand (attached for use in the County Fair) and moved due west to the river, jumped off, formed a skirmish line with two platoons abreast, and proceeded to move north.

The company was no sooner organized and moving than it met headlong a large group of VC almost nonchalantly streaming south, obviously out of ammunition and unaware of what they were blundering into. A slaughter commenced during which every VC soldier was killed, most by the withering enfilade poured into them and some by hand-to-hand fighting. It was thrilling. For once it was hard-nosed Marines in a classic skirmish assaulting straight into and vanquishing the enemy—like at Saipan or Inchon. Somewhat ironically, the company, in its assault up the river, recovered from the vanquished foe the very M1917A4 machineguns lost in the ambush (described above) that had earlier annihilated the Marine platoon that had patrolled the same route once too often. (It was later determined that the VC unit involved in both incidents was the RC-20th Company.) But the story is not yet complete, nor is the irony.

As the company thus proceeded up the river bank doing its dirty work, a pathetic voice came over the battalion tactical net. “Help,” he pleaded weakly. “I’m dying, and I’m the only one left,” or words to that effect. The battalion commander broke in, told the company commander to concentrate on the battle at hand, and addressed himself to the caller. What followed was a wrenchingly sad but at the same time eloquent conversation between the two. The colonel, like a father talking to his injured child, soothingly began, “Now, son, we hear you, and we’re going to help you.” Thence proceeded the necessary communications between the commander and the badly wounded young Marine (his shoulder had been shattered by machinegun fire) to effect a rescue. The Marine had no idea where he was, but the colonel was able to ascertain that he had an unspent white-star cluster with which he could signal his location. With the colonel gently and patiently telling him what to do step by step, on the count of three the flare popped only a few hundred yards from the assaulting force’s position. The company commander, having heard the entire communication, entered the net and told the colonel that he had the position in sight, and since the battle was well in hand, he could move there immediately by amtrac. Worried about the 3d Platoon and anticipating that was where they were, he turned over command of the skirmishing force to the senior platoon commander, and with several slightly wounded men in the belly of the amtrack who volunteered to fight if they had to, moved off in the direction of the wounded Marine. The thrill of battle quickly evaporated.

The scene was sickening. There indeed was the 3d Platoon, or what was left of it. The two helicopters had landed in a large, dry rice paddy—right in the middle of the RC-20th. The battalion commander, the one who had shown such kindness to a single wounded Marine, had little more than an hour before ordered that Marine and many others straight into the fray by helicopter without any effort to secure a landing site. He put them, not behind or alongside the company to which they were to be attached, where security for the landing and at least some semblance of mission orientation could have been established, but across the river from that company where they were to operate as a separate maneuver element. Essentially, in his zeal to aggressively close with the enemy, the battalion commander chanced everything on a blind guess. Unfortunately, he could not have guessed more wrongly.

The RC-20th immediately turned its attention from the Marines across the river and poured fire point-blank into the 3d Platoon as the Marines desperately scrambled out of the helicopters. In the frantically confusing situation, the helicopter crews had only one option—to abandon the already scattering troops and escape as best they could. With the troops running in every direction to get away from the helicopters and many men falling from the hail of fire, regathering everybody proved impossible. Six Marines were killed outright—most as they attempted to exit the helicopters. An additional 25 Marines and corpsmen were wounded, among them the platoon commander. The irony was made complete by the fact that the VC had at least two “old” Browning M1917A4 light machineguns that fired well, and both of the 3d Platoon’s brand-new M60s had immediately jammed. (Marine infantry units had begun replacing their M1917A4s with M60s in the early spring of 1966.)

When the company commander and his party arrived, only two pockets of men remained unhurt. Eleven were cowering in one bomb crater, and five more were grimly awaiting the end in another nearby crater. Then there was the wounded Marine on the top of the ground by himself. No person in any group knew if anybody else remained alive. The platoon sergeant, who was with the group of 11, later explained that they had attempted to maneuver, but with their machineguns jammed, there was little chance of gaining a balance of fire. Further, every time someone lifted his head above the edge of the crater the VC raked him with fire. Neither the group of 11 nor the group of 5 had a radio, and with the platoon commander and his radioman being shot down, all command and control were lost. From the moment the platoon landed to the moment the wounded Marine finally made his feeble appeal, the platoon was entirely cut off. They never had a chance.

There were, fortunately, some magnificent displays of professionalism, courage, and compassion by individual Marines and Navy corpsmen—displays by young enlisted men that in a way saved the bacon for us supposed “professionals” who had precipitated this shameful affair. Splendid leadership and heroism were displayed in the group of five, for example. Upon interview, four of the Marines, all Caucasians, reported how, as they crouched there, a young black machinegunner calmly said he would take charge. Assuming that they would be assaulted and killed or captured, he ordered each man to inventory his ammunition and trade around so that each had an equal share; each man would save one round to kill himself if necessary, and all would stand at the ready, back to back, and await the expected assault on their hole. Then they would go down fighting, taking as many VC with them as they could. Melodramatic stuff, but the Marines who told the story were deadly serious.

Earlier, and at the height of the bedlam, one of the corpsmen ran to one wounded Marine and gave him lifesaving first aid, then ran to the next fallen Marine, then to the next, and on to the next. Surviving Marines told that the corpsman, while attending the fifth wounded Marine, was shot down, a bullet through his head. He had knowingly sacrificed himself to do his duty. (He was still alive when evacuated but probably died on the way to the hospital.)

Somehow, probably from information reported by the helicopter crews that had taken the 3d Platoon into the fray, a helicopter medevac team arrived on the scene while the situation was still in chaos. The crew flew into the bloody field seven times—several times directly into enemy fire. During the first sorties they took so many rounds into and through their helicopter that they had to replace it in order to continue. Just after the detachment with the company commander arrived, the medevac crew returned for the sixth time and picked up the remaining wounded, including the lone Marine who had called for help, and then came back once more to pick up the dead. Wanting every able-bodied man to concentrate on the possibility of another attack, the company commander ordered them to stick to their weapons and proceeded alone to help the corpsman/crew chief load the dead on the helicopter. It was a gruesomely difficult task: the dead Marines, their bodies drained of blood, handled much like what might have been large sacks of potatoes that had been smashed by a sledgehammer; like so much mush they flopped about heavily and awkwardly in the effort to half heave, half yank them up into the helicopter. The bodies filled the belly of the helicopter and the crew chief had to sit atop the mound of corpses for the return flight. As the helicopter lifted off, the two men’s eyes met. On the crew chiefs face was an unforgettable look of shock and anguish. He seemed to be expressing, though without words, how terribly sorry he was that he could not have saved them all.

More melodrama, perhaps, but these descriptions, at the risk of pushing too hard to make the point, are inserted here to convey a sense of the human tragedy that more likely than not occurs when officers throw out the book, play it by ear, and cavalierly hasten to order other men into terrible situations.

What foolishness! Under the conditions, there was no clear reason to have been so hasty and to have risked so much. Had the 3d Platoon been dropped into that horrible trap sooner it would likely have suffered far worse, since the VC company that engaged them would have had more ammunition with which to finish the platoon off. Those who survived were extremely lucky; the VC did run out of ammunition and withdrew—south down the river bank and to their destruction at the hands of the skirmish line moving north.

Chance destruction of the RC-20th aside, should we have been dashing about looking for a fight so recklessly? Should any unit be dropped into an unsecured landing site unless the situation is desperate? In the case of the company to which the 3d Platoon was to be attached, their situation was not desperate. They were merely exchanging fire with the enemy across a river and had plenty of room to maneuver. The words “was to be” are intentional. The 3d Platoon never saw, nor was it ever seen by, the company to which it was supposed to have been attached; nor is it apparent that anybody in that company attempted to establish contact beyond perhaps trying to contact them by radio. One has to wonder why, when that medevac crew kept coming in across the river in plain sight and hearing, somebody in the company did not at least warn battalion that the to-be-attached unit might be in trouble. On the other hand, why should they have? Technically, the 3d Platoon was not yet an attachment under the company’s responsibility; it was still a separate command under battalion responsibility. Did the other company commander even know they were there? Owing to the sensitivity of the episode, such things were not discussed later. Whatever the whole story might have been, obviously the 3d Platoon was sacrificed for no other reason than a chance that through aggressive maneuvering in the blind they might keep a VC unit in place. That is insufficient justification for blindly jeopardizing the lives of a reinforced rifle platoon and several helicopter crews. The entire incident simply should not have happened, and it would not have happened had we better balanced our stewardship to our men with our disposition to aggressiveness. But then Marines are always aggressive, and commanders had little time to learn their trade and make their mark.

Returning to the saturation patrolling strategy, the troops derisively called the incessant patrols “activities.” Although in a few instances a single “activity” probably flushed out an enemy unit, and a few others may have deterred an enemy attack, the continuous employment of patrols around the clock kept the troops in a constant state of exhaustion while at the same time offering easy targets for an enemy that, as already indicated above, had the capability and cunning to take advantage of the opportunities that the strategy presented them. Didn’t this strategy violate or misapply any number of the principles of war, those principles that are considered the “enduring bedrock of doctrine”? Arguably, such a strategy can be justified under the principles of objective, maneuver, and offensive. But what about mass, economy of force, unity of command, security, simplicity, and surprise? The enemy always knew right where we were, and they knew that we would constantly present ourselves in vulnerable little pieces and that those little pieces would wander about seemingly willy-nilly over the same terrain day after day and night after night. And complicating the issue, all patrolling had to be orchestrated, lock step, around those elaborately plotted and timed H & I fires. All the VC had to do was observe, plant mines and booby traps, and use the hit and run tactics that they often employed in coordination with deadly ambushes. That is, the Marines seemed to be employing a strategy that in violating most of the principles of war all-too-easily accommodated the strategy consistently being employed against them by enemy commanders who took advantage of every element as if they had conceived those bedrock principles themselves. Add to that a tendency on the part of Marine commanders to be overly aggressive and the conditions for disaster were ripe.

Moreover, still another factor mitigated against us—our general disdain of the enemy. Were the VC equal to the challenge? By all means they were. They probably were as adept at employing mine warfare as any military force in history. We saturated the battlefield with little patrols and chased after every burst of fire; they saturated the battlefield with traps, baited us with scattered fire, and waited for us in ambush. The VC were not merely a bunch of stupid little people in black silk pajamas, conical straw hats, and shower shoes made from old tires. They were intelligent, cunning, able, well trained, largely professional, and relentless. And they were fanatically determined killers. They hated us passionately and would never rest until we were gone from their homeland forever, dead or alive. Having no mass, no fighter planes, no artillery or tanks or naval guns or B-52s with which to pulverize the landscape with arc lights, they dug ditches, tunnels, and caves, and planted barbed wire, booby traps, and mines—all brilliantly and perfectly adapted to counter the strategy of aggressive saturation patrolling. The so-called ambushes we claim to have employed in tandem with patrols were nothing more than patrols that stopped longer at one of their checkpoints. In fact they were a joke; it is likely that Marines never closed a successful ambush against the VC, since the VC always knew where the ambushes were. Perhaps one of the lessons we seemingly never learned is that we were fighting a smart and dedicated—and sophisticated—enemy.

The RC-20th VC company made only one mistake on 21 May: It abandoned an extremely effective strategy and fought for too long in one place. Nevertheless, up to the moment of destruction it had been enormously successful; it annihilated one platoon and almost annihilated another in addition to killing several more with mines and booby traps (including a battalion commander) before succumbing to their own annihilation. Regardless of their relative success, the other VC in the region probably learned well from the RC20th’s one big mistake. We, however, seemingly never learned. Rather than learning, our revenge on the RC-20th and recovering our weapons may even have been seen as a vindication of our strategy, not a lucky stroke owing to a VC mistake that was not likely to be repeated.

After the incident of 21 May, the company took up defensive duty for the southern part of the battalion command post perimeter at Hill 55—with the usual additional responsibility of saturation patrolling. The company was so short of personnel that squad patrols (the commonly employed patrol was squad size) consisted mostly of about eight men under the command of a lance corporal or corporal. That is, those maneuver elements that were supposed to be able to fix and destroy a fanatic enemy were little more than glorified fire teams often led by newly arrived junior NCOs barely older and better trained than the youngest and least trained men under them. It seemed little short of suicidal to send these weak little units out on the extended “activities” expected under division policy. In early June the battalion commander at Hill 55 was urged by subordinates to beef up offensive patrols to platoon size for several reasons, among them leadership and experience, firepower, maneuver capability, and sheer size sufficient to resist an ambush. The battalion commander naturally hesitated making a decision that might be considered contrary to division policy, but on the other hand, he could not dismiss the rationale presented. On the merits, and possibly somewhat influenced by the tragic results of his decision of 21 May, he approved increasing the size of offensive patrols from squad to platoon.

What about troop strengths? In 1966 the 3d Marine Division was chronically short of personnel. The above-described company is a good case in point; it averaged about 150 men on any given day. Casualties totaled 100 between March and July, and 4 of them were lieutenants. These painful losses were in addition to the normal attrition that arised as a result of the single-year rotation policy that prevailed throughout the Vietnam War. This policy resulted in a steady drain of experienced men, often at times when units could ill afford to lose them. These endemic shortages in both numbers and experience, in combination with the requirement to saturate the operations area with patrols around the clock and the Marine Corps’ “can do” spirit, created an extremely dangerous, sometimes almost debilitating situation. It appears that the Corps’ personnel administration structure was not geared to keep up in 1966. Is it now? If not now, or if always fighting shorthanded is taken for granted, are field commanders prepared, either by

training or philosophy, to make the necessary operational adjustments to keep the fighting machine healthy enough to carry out the mission?

Combining enemy mines, booby traps, caves, tunnels, wire, dikes, ditches, ambushes and selected attacks with our willy-nilly “activities” carried out by exhausted and understrength units and the VC’s uncanny ability to orchestrate the mix to their advantage, the early part of the war was hell. It was nasty, humorless, exhausting, and terribly discouraging. In another kind of bitter irony, an awful incident occurred in late June 1966 that seemed to neatly but searingly bind up the whole ugly mess.

Near the river that flows past Hill 55 on the south, the rice paddies did double duty by yielding rice during the northeast monsoon and corn during the dry season. By June the corn stood about 7 feet high, just the perfect addition to the dikes, ditches, wire, and mines to present patrolling Marines with bad situations. Late one afternoon the 1st Platoon while on patrol entered one of those rice paddy/cornfields. At the far side of the field the point squad came abruptly upon a high dike behind a ditch and topped by barbed wire. The squad leader halted his unit and radioed the situation to the platoon commander, who decided to come up to see for himself. He unwisely brought with him the platoon sergeant, platoon guide, and the platoon’s complement of radiomen and corpsmen. They approached, then intermingled with the squad, which had already become badly bunched up—first because of the dense growth and then from piling up on the fenced dike. The platoon commander looked the situation over and ordered the squad to move around the obstacle and continue on the previously assigned heading. And to his credit he ordered everybody to spread back out since they were so dangerously bunched up.

It was too late. The first man to move tripped a large mine planted at the base of the dike. Two Marines, including the platoon sergeant, were killed instantly. The platoon commander was saturated with shrapnel, the man who tripped the mine had both feet blown off, and 14 others were also wounded, most of them seriously. It was probably the worst mine tragedy in the war up to that point.

The physical evidence of the tragedy was starkly clear upon inspection the next morning. Shrapnel had cut a swath through the com, and the broken stalks lay in an arc away from the point of the blast. Thick puddles of coagulated blood marked the place where every Marine had fallen, and the puddles were close together. When the report of the tragedy reached division, a formal investigation was immediately launched with both the company and battalion commander being named as parties. The investigating officer was a lieutenant colonel who had just arrived in country and was being assigned to the 9th Marines. Fortunately, before he came down to Hill 55 he took the opportunity to interview the wounded before they were airlifted out of country. Most or all who were able to speak reported that before the incident strong measures—to include a 10-pace minimum interval—had been consistently carried out to avoid just such a tragedy, and the investigation concluded without culpability being assigned. Not that this in any way ameliorated the tragedy that had occurred.

With the exception of the events of 21 May, every casualty suffered by the company between March and July 1966 was due to mines, booby traps, and VC ambushes while the men were carrying out “activities” during which they never saw the enemy.

Did our approach work? Did it allow us to accomplish the objective? Two years after returning home I bumped into a classmate from The Basic School at the Camp Pendleton post exchange. He had just returned from Vietnam. He had been a rifle company commander in the vicinity of Hill 55. He recalled that it was nasty, humorless, exhausting, and terribly discouraging. And his company suffered many casualties on mines and booby traps while hardly ever setting eyes on the enemy. His was at least the 12th rifle company to have patrolled Hill 55 (at least four battalions had been assigned in that vicinity between 1965 and 1967). How many more companies bled there and to what end? Was it all in vain?

Suffice it to say, in conclusion, that battle commanders should stick by the book (the basics) as much as they can—at least as regards individual and unit security—and play it by ear only when the conditions absolutely dictate. But at the same time we must be flexible enough to reassess and respond, intelligently and quickly, boldly even, to whatever strategy the enemy may employ to counter us. Battle commanders must be ever vigilant regarding the condition of their men, and allow that condition to influence their approach to the mission. It is true, whether we like it or not and “can do” spirit notwithstanding, Marines can easily be pushed to exhaustion and can absorb bullets and shrapnel just as easily as any other foot soldier. If they are killed or maimed because of constant exhaustion, or while on details that foolishly play into the hands of the enemy, it is not their fault; it is their commander’s fault. And surely, one of the deadliest ways to play into the hands of the enemy is to blindly drop troops into unsecured landing zones.

Lastly, the commander’s responsibility as the guardian of the welfare of his men must take precedence over any personal motive. How often are decisions on the battlefield entirely consistent with the real mission, and how often are they influenced by the urge, for example, to be dashing, aloof, and cavalier? In the final analysis, the best battle commanders, in addition to being highly competent, are—consistent with the mission—also highly dedicated to the welfare of their men. That any Marine’s vanity be the cause of another Marine’s death is more than tragic; it is criminal.