Operation RESTORE HOPE in Somalia

By: Maj Norman L. CoolingPosted on August 15,2025

Article Date 01/09/2025

A Tactical Action Turned Strategic Defeat

>Originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette, September 2001. The authors biography is available in the original edition.

‘Me and Somalia against the World, me and my clan against Somalia, me and my family against the clan, me and my brother against my family, me against my brother.’

-Somali Proverb

From 1992 to 1994, U.S. forces deployed to the African nation of Somalia to conduct humanitarian and peacekeeping missions as part of Operations PROVIDE RELIEF and RESTORE HOPE. Initiated during the Bush Administration and continued under the Clinton Administration, the United States undertook these operations in support of a greater United Nations (U.N.) effort. The United States’ primary role evolved into providing security for various humanitarian relief units and agencies while attempting to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure. In short, the United States assumed responsibility for providing the muscle for the operation. An overly ambitious U.N. mandate, coupled with an exceptionally poor command and control apparatus, eventually inhibited the operational commander’s ability to properly shape the battlespace for the introduction of forces at the tactical level. A skilled Somali tribal warlord capitalized on this weakness by confronting U.S. military power asymmetrically, bringing U.S. forces into the close confines of a city he largely controlled. This resulted in an embarrassing, though arguably successful, tactical mission that, in turn, produced a strategic defeat for both the United States and the U.N.

Strategic Setting and Conflict History

Somalia is a landmass of approximately 250 square miles on the Horn of Africa—the northeast coast of that continent. (See Figure 1.) It is 24 hours away from the United States by air, and several weeks away by sea. Mogadishu, the nation’s capital, is a typical Third World city. Normally a city of about 500,000, it had grown to as many as 1.5 million by 1992, due to a refugee problem generated by drought, civil war, and an accompanying humanitarian crisis. The city’s infrastructure is largely inadequate for the size of its populace. Densely filled with poorly constructed concrete buildings, Mogadishu’s overcrowding and poor sanitation have created a breeding ground for disease. Lines of communication (LOC) within the nation are virtually nonexistent. Mogadishu contains the nation’s largest airport, while the entire nation contains just seven other paved airstrips. No functioning telephone or communications system exists in the nation.

Food and water in Somalia are scarce due to the drought that has stricken much of east Africa during the last decade. The situation has generated an

attitude of hopelessness among most of the inhabitants, many of whom seem only to wait for death. Many Somali men are addicted to khat, a mild amphetamine. While some Somalis fish in an attempt to provide for themselves and their families, most seem to have forgotten how to work altogether. Looting and black market activities are commonplace.

Since 1988, a savage civil war between approximately 14 clans and factions that make up Somali society has severely exacerbated the food shortage. For more than a decade, the area was at the forefront of Cold War competition and, as a result, large numbers of individual and heavy weapons were available to the clans. Although Somalis are devout Muslims (in many of the war-ravaged locations, mosques were the only buildings left standing), Somali culture stresses the unity of the clan above all else. Alliances are made with other clans only when necessary to elicit some gain. Weapons, overt aggressiveness, and an unusual willingness to accept casualties are intrinsic parts of the Somali culture. Women and children are considered part of the clan’s order of battle. People of western culture and heritage typically have great difficulty in accepting the Somali view of life. As MG Thomas M. Montgomery, who served as Commander, U.S. Forces, Somalia (USForSom), stated, “It’s impossible for an American mother to believe that a Somali mother would raise children to avenge the clan.”

The most powerful of these clans in Mogadishu, and the largest in all of Somalia, was the Habr Gidr, led by warlord Mohamed Farrah Aideed. Aideed had been educated in both Italy and the Soviet Union. He had served Somalia’s dictator, Mohamed Siad Barre, as Army chief of staff and then as ambassador to India, before leading a coup against him in 1991. Siad Barre had ruled a united Somalia by terror for 20 years. Aideed had worked with other clans to overthrow Siad Barre, but following the successful coup, the Habr Gidr could not consolidate power. Several of the northern clans attempted to secede. With drought conditions worsening and starvation setting in, clan warfare and banditry became commonplace. Pillaging and looting became methods of survival, and most of the young Somali men were “guns for hire.” Somalia sank into total anarchy. By early 1992, more than one-half million Somalis died of starvation with at least one million more threatened.

Recognizing the human tragedy ongoing in Somalia, in April 1992, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 751, establishing United Nations Operations in Somalia (UNOSom). UNOSom was tasked to provide humanitarian assistance and to “facilitate” the end of hostilities in Somalia. It soon became evident, though, that not enough food, water, and medicines were making it to the people who needed it. Instead, bandits and the warring Somali clans were stealing and confiscating the relief supplies. The 50 UNOSom observers could not fulfill their mission alone, prompting the U.N. to request assistance from the United States. The Bush Administration responded by initiating Operation PROVIDE RELIEF that lasted from 15 August through 9 December 1992. This operation, predominantly an Air Force effort, airlifted food into Somalia from the neighboring nation of Kenya. Commanded by BGen Frank Libutti, PROVIDE RELIEF brought more than 28,000 metric tons of desperately needed supplies into Somalia.

Nevertheless, by December 1992, it was clear that the combined U.S. and U.N. effort was still insufficient to protect the humanitarian effort as bandits continued to inhibit relief distribution. In order to mitigate the disaster, the United States would need to commit ground forces to provide security for international relief distribution points. Subsequently, on 3 December 1992, the U.N. passed Resolution 794, stipulating that the United States would both lead and provide forces to a multinational coalition titled the United Task Force, or UniTaf. To fulfill this role, on the following day President Bush announced the initiation of Operation RESTORE HOPE, under the command of Marine LtGen Robert B. Johnston. The UniTaf and RESTORE HOPE combined the humanitarian relief mission with purposeful, limited military action to ensure the security of the relief effort. Both the United States and the U.N. intended that these operations would be of short duration and that the United States would pass its responsibility back to UNOSom once the situation was stabilized.

UniTaf remained in existence from 9 December 1992 through 4 May 1993, and involved more than 38,000 troops from 21 nations (including 28,000 Americans). Leading the UniTaf, U.S. Marines initiated the operation with an amphibious assault as a show-of-force demonstration. The effects of this highly publicized, predawn landing were somewhat compromised by the barrage of western reporters spotlighting Marines on the beach. Nonetheless, the Marines followed up with a series of quick, decisive, and largely unopposed air and ground tactical maneuvers that seized key terrain in and around Mogadishu. The fact that the major warring factions agreed to an armistice within 2 days of the initial landing proved the Marines’ effectiveness in establishing operational dominance in the region.

On 13 December 1992, the Army’s 10th Mountain Division (Light) joined the Marines in Mogadishu and along with other U.N. forces, moved to secure relief distribution facilities in established humanitarian relief sectors (HRS). The UniTaf created the HRS to provide command and control boundaries between the participating units. Within these HRS, U.N. forces were responsible for supporting and providing security to various nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The focus during this period was to disarm the Somalis, to include locating and seizing arms caches, as well as encouraging the Somalis to voluntarily turn in their weapons. As a result, increasing amounts of relief supplies were successfully distributed throughout the nation, curtailing starvation in many areas.

The UniTaf, under the leadership of LtGen Johnston and U.S. Ambassador to Somalia, Robert Oakley, made it a point to actively work with the various clan leaders as the only recognized leadership in the country. Then-MajGen Anthony C. Zinni, who served as UniTaf’s director of operations, later explained UniTaf’s reasoning when he stated:

Everybody with some degree of authority, even if it’s out of the barrel of a gun, you’d better give them a forum in which to bring their case. When they’re isolated, there’s no recourse other than to violence.

They ensured that their disarmament efforts were done in such a way as to avoid embarrassing or provoking them. During an interview, MajGen Zinni further noted:

Our headquarters was in [Aideed’s] area, Mogadishu, our main logistic lines and bases, the air base and the airfield, and the port were in his area of control, so it was very important that we had him cooperating, especially in the beginning.

Zinni recalled that, because the U.S. actively engaged Aideed, he often assisted U.S. operations by offering advice:

… he would tell us, ‘Don’t just go out to the hinterlands unannounced. You may have an unintended clash with the militia or a group out there. Make sure they know you’re coming and the purpose of your visit. It will prevent any unintended violence. Come with NGOs … with food, so they look at you as not just another gun club out there, but associate the food and medicine with you so you’re there for some positive purpose.’

Largely because of this engagement strategy, the UniTaf succeeded in its missions of stabilizing the security situation to facilitate humanitarian relief. Prior to its departure, the UniTaf also worked with the 14 major Somali factions to agree to a plan for a transitional or transnational government. Realizing the importance of the large U.S. contribution, U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali repeatedly delayed the termination of UniTaf in hopes of effectively disarming the Somalis and creating conditions conducive to nation building. Ali Mahdi, leader of the Darod clan (the clan of former dictator Siad Barre), and several other leaders of smaller clans were enthusiastic about the U.N.’s nation building efforts, but Aideed was determined that power would not be shared. Aideed felt that his Somali National Alliance (SNA), comprised of the Habr Gidr and three allied Somali clans, had earned the right to rule the country since they had borne the lion’s share of risk and pain in overthrowing Siad Barre. The Habr Gidr was highly distrustful of Boutros-Ghali. A long-time enemy of Aideed, Boutros-Ghali had worked against the SNA’s revolutionary movement when he was an Egyptian diplomat. Accordingly, the Habr Gidr believed that Boutros-Ghali was attempting to restore the Darod to power. Thus, many Somalis questioned Boutros-Ghali’s legitimacy from the beginning.

With the United States impatient to withdraw its forces, Boutros-Ghali finally acquiesced, and Security Council Resolution 814 formally created UNOSom II on 26 March 1993. This resolution comprised the first U.N.-directed peacekeeping operation under the Chapter VII enforcement provisions of the U.N. Charter. It required the UNOSom II forces to disarm the Somali clans while providing humanitarian relief and conducting significant nation building and peace enforcement tasks. Special Representative of the Secretary-General Jonathan Howe, a retired U.S. Navy admiral, headed UNOSom II, while Turkish Gen Cevik Bir served as the commander of the U.N. multinational contingent. The majority of American forces within Somalia soon redeployed home. Just 4,500 American troops remained in the country, now under the command of MG Thomas M. Montgomery, USA, as Commander, USForSom. Over 3,000 of these troops were logistics support personnel, but they also included approximately 1,150 soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division who were designated as UNOSom II’s quick reaction force (QRF). The QRF would assist UNOSom II in military operations that were beyond the latter’s capabilities. MG Montgomery operated under two chains of command, serving as the U.N. military forces’ deputy to LtGen Bir, while remaining under the command of the commander in chief, U.S. Central Command (CinCUSCentCom), Marine Gen Joseph Hoar.

ADM Howe and LtGen Bir adopted a philosophy and operational strategy very dissimilar from that employed by their UniTaf predecessors, Ambassador Oakley and LtGen Johnston. Instead of engaging the clan leaders, Howe attempted to marginalize and isolate them. ADM Howe ignored Aideed and the other clan leaders in an attempt to decrease the warlords’ power. Disregarding the long-established Somali cultural order, the U.N. felt that, in the interest of creating a representative, democratic Somali Government, they would be better served by excluding the clan leadership. The policy reeked of arrogance coupled with cultural ignorance.

Consistent with this strategy, U.S. operations became increasingly aggressive under the U.N. mandate. American and other U.N. forces conducted several air assault operations to deny the warring factions freedom of movement by securing key points in and around Mogadishu. U.S. force protection concerns escalated when a sniper killed a U.S. soldier. When a convoy of technicals (civilian pickup trucks mounting machineguns) attempted to enter a restricted area in the town of Kismayo, the Army used firepower as a means of force protection by destroying it with a flight of AH-1 attack helicopters. Many Somalis began to view the U.N. forces, and particularly the U.S. forces, as a direct threat instead of an impartial mediator and legitimate stabilizing force. As Aideed saw it, ADM Howe was subordinating the U.S. forces to his nemesis, Boutros-Ghali. Somali antagonism toward the Americans grew proportionally with the increasing U.S. willingness to restrict native movement and enforce these restrictive policies with lethal fires. U.S. forces, highly concerned with force protection, began to adopt a siege mentality within their HRS. Maintaining a working relationship with the local populace in Mogadishu and other urban areas now took a backseat to force protection concerns.

Tensions continued to escalate as the United States began to redeploy its forces and gradually turned command and control over to the UN. Since the U.N. did not replace many of the Americans responsible for controlling access within the HRS, several warlords, no longer operationally isolated, made their way back into the urban areas. In February, a Somali faction led by Col Morgan seized Kismayo. Fighting rapidly broke out with another Somali gang led by an ally of Aideed, Col Jess. Four Marines were wounded before Morgan was persuaded to withdraw. The U.N. blamed this incident on Aideed and soon labeled him the biggest obstacle to creating an environment within Somalia that was conducive to long-term conflict resolution. From Aideed’s viewpoint, the ambitious U.N. peace enforcement and nation-building mandate ultimately threatened his power base.

Under ADM Howe’s direction, U.N. forces then began conducting operations, such as armory inspections, without giving the warlords advance warning. On 5 June 1993, they conducted an inspection on an Aideed militia armory in Mogadishu. Aideed’s militia feared that the U.N. was actually moving to seize control of their clan radio station, “Radio Aideed.” They reacted by killing 24 Pakistani soldiers and injuring several more during an ambush as the U.N. forces returned from the inspection. The angry Somali backlash was so spontaneous and violent that Pakistani soldiers in the area guarding feeding stations were also attacked. Women and children, who were often rifle carrying combatants, opened these attacks. These tactics shocked the U.N. troops, who were unaccustomed to Somali culture. The Pakistanis were later heavily and unfairly criticized because they opened fire on the women and children. This incident led to a U.N. resolution calling for the arrest of those responsible for the ambush, thus adding the apprehension of Aideed to UNOSom II’s mission. The U.N. mission effectively transitioned from a neutral, peacekeeping role into a counterinsurgency campaign oriented at eliminating a specific clan’s influence. In hindsight, this resolution ignored the fact that the clans were the most deeply imbedded aspects of Somali society and culture. It would prove to be the decision that set the stage for strategic failure.

The day following the SNA ambush of the Pakistanis, ADM Howe began lobbying the Clinton Administration for special forces to assist in capturing Aideed. Initially unable to obtain this support, ADM Howe and LtGen Bir directed 3 days of AC–130H and AH–1 helicopter attacks and QRF raids on Aideed’s weapon storage sites and radio station. On 12 July 1993, ADM Howe directed an AH–1 attack on an SNA headquarters building, known as the Abdi House, in an attempt to eliminate the more radical members of Aideed’s clan. The raid resulted in several deaths and caused the more moderate members of Habr Gidr to lean further against the United States. ADM Howe then reversed course, halting his offensive and labeling Aideed a war criminal. He put a bounty of $25,000 on Aideed’s head in hopes that members of his clan would be persuaded to betray him. Because the amount was considered so small, however, the SNA actually viewed it an insult. All the while, the American presence in Somalia continued to decrease as U.S. forces redeployed home.

Analyzing the American and United Nations Campaign Plans

The shared U.N. and U.S. strategic objective in Somalia was to create conditions within the nation that would facilitate humanitarian relief and promote a lasting resolution of the conflict. During the UniTaf period, Ambassdor Oakley and LtGen Johnston believed that the best means of pursuing this objective was by working with the leaders of the various clans—the center of Somali society that they correctly identified as the Somali operational center of gravity. With a robust ground force, they demonstrated their resolve while playing the role of an honest broker. Conversely, during UNOSom II, U.N. Special Representative Howe began to view a single clan, Aideed’s Habr Gidr, as the center of gravity blocking mission progress. Similarly, he saw Aideed’s personal security as a critical vulnerability. If Aideed could be captured and brought to justice, he would be isolated from his public support, and the Habr Gidr could be persuaded to share power with their rival clans.

After ADM Howe’s repeated political cajoling, the Clinton Administration, although still committed to withdrawing U.S. forces from Somalia, finally agreed to deploy a special operations unit to begin strike operations to capture Aideed and other key leaders of the Habr Gidr. This decision was made against the advice of Gen Hoar, CinCUSCentCom. The special operations unit—Task Force Ranger (TF Ranger) commanded by MG William F. Garrison—would conduct a three-phase operation. Phase I, from 23–30 August, would constitute a preparation period immediately following their deployment. During Phase II, which would last until 7 September, TF Ranger would locate and capture Aideed. Finally, during Phase III, they would target Aideed’s command structure. Despite the fact that ADM Howe’s overzealousness in conducting attacks on Habr Gidr headquarters and posting a bounty on Aideed’s head had long ago forced the warlord into hiding, U.S. officials optimistically felt that the Habr Gidr leadership could be removed within the month.

Analyzing Aideed’s Campaign Plan

Aideed’s objective remained to consolidate control of the Somali nation under his leadership. This required him to defeat the competing warlords, but he could not do so given the presence of the U.N. and U.S. forces. The U.N.’s operational center of gravity was clearly the superbly trained and technologically advanced American military forces, which Aideed knew he could not attack directly. Yet, Aideed had a clear understanding of the difference between western culture and his own. This understanding helped him identify a potential American vulnerability. Aideed knew that Americans had a profound distaste for casualties and doubted their resolve with regard to the humanitarian effort in Somalia. If he could convince the American public that the price for keeping troops in Somalia would be costly, or that their forces were hurting as many Somalis as they were helping, he believed that they would withdraw their forces. If they left, the powerless U.N. would leave soon thereafter, leaving him free to pursue his goal of consolidating Somalia under SNA leadership.

Accordingly, Aideed’s strategy centered on Mao Ze Dong’s asymmetric, or “indirect,” approach. He would attack the American public’s desire to remain involved in Somalia. By drawing U.S. forces into an urban fight on his home turf in Mogadishu, Aideed believed that the city’s noncombatants would make it difficult for U.S. forces to employ their robust firepower (upon which they relied heavily) without serious strategic repercussions. In the close confines of the city, much of America’s technological superiority would be moot. (See Figure 2.) If the Americans were unwilling to risk harming civilians, his forces would inflict heavy casualties on U.S. servicemen, thereby degrading U.S. public support for operations in Somalia. If, on the other hand, the U.S. forces were willing to fire indiscriminately as a means of self-preservation, the Somali casualties produced would likely have the same intended effect.

Aideed had approximately 2,000 loosely organized SNA militia at his disposal. The SNA were well armed with large quantities of assault rifles, rocket propelled grenade (RPG) launchers, antiaircraft guns, mortars, and light artillery, as well as a small number of tanks. It also had a significant number of technicals. In the wake of UniTaf’s departure, Aideed reentered Mogadishu and quickly rearmed and reorganized while seeking to regain his control over the populace. Together with Col Sharif Hassen Giumale, an officer familiar with guerrilla insurgency tactics and likely the SNA’s senior tactical commander in Mogadishu, Aideed recognized that the American helicopters were potentially a critical tactical vulnerability. The warlord sensed that if he shot down a helicopter, it would cause the U.S. forces to consolidate around the helicopter, thereby allowing the Somalis to pin them in one area. This would inhibit “quick in, quick out” U.S. tactics and, instead, the Americans would be forced to remain in the confines of the city for longer periods of time where the SNA could extract a price. Accordingly, he brought in some fundamentalist Islamic soldiers from Sudan, who had experience in downing Russian helicopters in Afghanistan, to train his men in RPG firing techniques. Complementing his strategy, Aideed paid and threatened civilians to participate in “rent-a-crowds” that would cover his militiamen.

Campaign Execution

By the time TF Ranger deployed to Somalia, Aideed was in hiding. MG Garrison was forced to rely heavily on paid Somali informants to locate and track Aideed and others in the Habr Gidr. This intelligence collection technique met with mixed results and several embarrassments, as they experienced great difficulty in locating Aideed. As a result, Phases II and III of the planned operation merged, and they sought to capture Habr Gidr leaders whenever and wherever they could find them. On TF Ranger’s first mission, poor human intelligence (HumInt) caused them to greatly embarrass Washington by inadvertently arresting a group of U.N. employees. A later raid similarly proved disastrous as they stormed the residence of Somali Gen Ahmen Jilao, a close U.N. ally and the man they were grooming to lead the Somali police force. Operational security remained difficult. In one of their first “top secret” missions, the troops of TF Ranger were surprised to see themselves on CNN before they had even removed their gear. Because the Rangers employed the same aerial raid techniques repeatedly, they largely forfeited the advantage of tactical surprise. Meanwhile, Washington continued to grow impatient with MG Garrison.

The United States’ inability to locate Aideed turned him into a folk hero. TF Ranger’s violent surprise attacks were also causing Somalis outside the Habr Gidr to question the legitimacy of U.S. forces in the country and further swayed the moderates toward Aideed. It was fine to intervene in the country to feed the starving and even to help establish a peaceful government, but purposefully targeting Somali leaders as criminals was a different thing entirely. TF Ranger’s aggressive employment of firepower during a number of surprise raids caused several noncombatant casualties and created a general fear and hate of the Rangers.

On 3 October, TF Ranger prepared to strike a target within Somalia’s Bakara Market district, where two of Aideed’s lieutenants were reported to be in hiding. Since the Marines had pulled out of Mogadishu with the end of UniTaf, the U.N. forces, comprised mostly of Pakistanis, had refused to enter the Bakara Market area. It was well known that this area was filled with weapons and that very aggressive Habr Gidr militia units protected the weapons trade there. As a result, Aideed controlled his own fiefdom within the city.

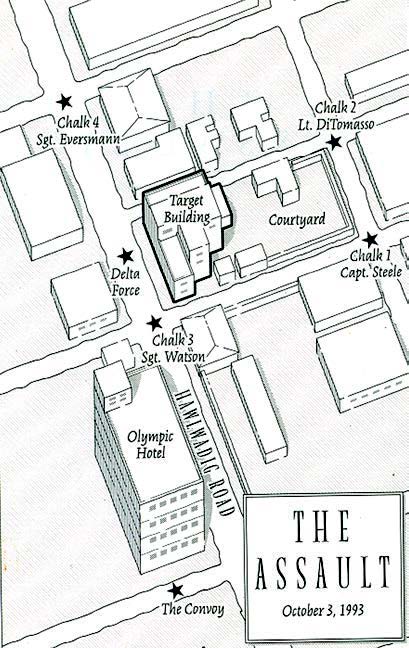

The tactical plan for the raid was one that TF Ranger had employed several times before. First a Delta Force team would insert by helicopter directly onto the three-story target building while four Ranger teams isolated the building by securing the four street corners immediately around it. (See Figure 3.) Once Delta secured the prisoners, a convoy of cargo trucks, escorted by assault-configured HMMWVs, would arrive at the target building from the American base just 5 minutes away and pick them up. All the while, attack helicopters would loiter in the area to provide rotary-wing close air support if needed. Simultaneously, OH–58 observation helicopters, P–3 spy planes, and satellites would ensure that MG Garrison could watch the situation unfold on the video screen in his command post. The raid was to take no longer than 1 hour.

Even as the Blackhawk helicopters were approaching the target buildings, Somalis could be seen setting tires ablaze—a technique they used to mobilize the SNA militia. The Somali’s had witnessed six TF Ranger raids now and knew what to expect. As the Delta troops inserted, throngs of Somalis began to crowd toward the target building. The rules of engagement (ROE), which stipulated that the Rangers were to shoot only when someone pointed a weapon at them, quickly became unrealistic. The SNA fired from crowds filled with women, children, and the aged and infirm. In one instance, a Somali

shooter had the barrel of his weapon between the women’s legs, and there were four children actually sitting on him. He was completely shielded in noncombatants, taking full cynical advantage of the Americans’ decency.

The Rangers had to decide between killing all those in the crowds or watching their fellow soldiers be killed. They logically chose the former.

The situation became increasingly confused as friction came into play. A young soldier fell from his fast rope as one of the Ranger teams was inserted at the wrong intersection. Some Rangers began firing at Delta Force soldiers. Others were immobilized with fear. Ground RPG fire struck one of the loitering Blackhawk helicopters, causing it to crash. Within just a few minutes, a second Blackhawk crashed. Several other helicopters were disabled. Aideed’s strategy was working. The convoy was forced to split to deal with casualties. One portion of the convoy got lost while attempting to move to the site of the first downed helicopter under intense Somali fire from all directions. Excessive layers of control prohibited the P–3 spy planes from communicating directions directly to the convoy, causing a delay of instructions that caused the convoy to miss turns. The convoy literally circled through the most dangerous part of the city, repeatedly stumbling into kill zones. Casualties continued to mount. The second downed helicopter site was overrun. All but one American pilot at the site, CWO Michael Durant, were killed. CWO Durant became a prisoner, and the Habr Gidr later paid the rival clan that captured him so that they could use him as a bargaining chip with the United States.

Because Secretary of Defense Les Aspin had denied an earlier request by MG Montgomery to deploy U.S. armored forces, it took precious hours to augment the U.S. light infantry QRF with Malaysian and Pakistani armored units. The QRF had not trained with the Malaysians and Pakistanis. Twenty-four hours after TF Ranger was initially inserted, the QRF was finally able to rescue them near the first helicopter’s crash site.

The United States suffered 91 casualties during the Battle of Mogadishu, to include 18 killed and 73 injured. The task force also lost five downed Blackhawk helicopters and numerous damaged vehicles. SNA militia losses during the battle are unknown but, by all estimates, collateral damage was significant. U.S., U.N., and SNA estimates all indicate that 3,123 Somalis were killed and another 814 injured during TF Ranger’s raid. According to one of Aideed’s lieutenants, just 133 of these casualties were members of SNA militia.

Despite the fact that TF Ranger had accomplished its original tactical mission by capturing 24 Habr Gidr clansmen, the American public viewed the price as far too high. By the next day, pictures of dead American soldiers being brutalized and dragged through the streets of Mogadishu were being broadcast on television screens throughout the world. The Congress, sensing a backlash in public opinion, pressured the President to end U.S. involvement. Accordingly, the President decided that the United States would withdraw not later than the end of March 1994. President Clinton brought back former U.S. Ambassador Oakley to negotiate Durant’s release. Ambassador Oakley told Aideed that TF Ranger’s mission was over and that U.S. military involvement was to end in March, but the President wanted CWO Durant released immediately without conditions. A strong U.S. force was deployed to the region to reinforce America’s intention of rescuing Durant if Aideed refused. The warlord released the pilot almost immediately. Within a few weeks, U.S. Marines escorted Aideed to renewed peace negotiations. As a result of those negotiations, President Clinton ordered the release of every man previously captured during TF Ranger’s missions. Soon after the U.S. withdrawal in March, the U.N. mission failed. Without U.S. muscle, the U.N. could not hope to build a government in Somalia without Aideed’s assistance, and Aideed would not accept sharing power with other clan leaders.

Operational-Level Assessment

Tactically, one might argue that the battle of Mogadishu was a success. TF Ranger succeeded in capturing 24 suspected Aideed supporters, to include two of his key lieutenants. Given the appropriate response at the strategic level, some even argue that it had the potential to be an operational success. After accompanying Ambassador Oakley to a meeting with Aideed soon after the battle, MajGen Zinni described the clan leader as visibly shaken by the encounter. He believed that the SNA leadership had had enough of the fighting and was prepared to negotiate. Unfortunately, the Clinton Administration failed to shape the strategic battlespace for operational success from the outset by neglecting to inform and convince the American public—and its elected members of Congress—of the necessity for employing American forces to capture Aideed. The President was left with little recourse after the battle in Mogadishu but to avoid further military confrontation.

Despite this strategic failing, the operational commanders might nonetheless have avoided the casualties in Mogadishu, and the subsequent public and congressional backlash, had they better communicated among themselves and worked with unity of effort. Recognizing the complications created by the separate U.S. and U.N. chains of command and missions, ADM Howe, along with Gen Hoar and MGs Montgomery and Garrison should have established the architecture needed to facilitate integrated planning and execution for each mission conducted. These commanders failed to “operationalize” their plan. They did not properly link U.S. strategic objectives and concerns to the tactical plan. The TF Ranger mission was an ill-conceived, direct operational attempt to obtain a strategic objective in a single tactical action. Yet, apparently neither Gen Hoar nor MG Garrison considered the implications of a failure given the lack of strategic groundwork. Were they to have made such an assessment, it is doubtful that they would have elected to pursue such a high-risk evolution. In this light, U.S. military operations in Somalia during the UNOSom II phase must be viewed as an operational failure.

Command and Control

MajGen Zinni summed up UNOSom II’s command and control failure well:

We had a U.N. operation. We had General Bir in charge of the U.N. forces. The U.S. forces were really under his deputy, General Montgomery, but then General Montgomery [didn’t have] operational command authority [of those forces]. The CinC, General Hoar, provided the forces in some sort of tactical control, but obviously never relinquished command. That’s another myth; the command was never relinquished to U.N. forces, so all but U.S. forces were under this U.N. command and control. I think there were forces on the ground that were under Chapter VI instructions. I think you might find the Germans and others that were there under Chapter VII. There were forces off the coast that would come in and react that had another chain of command, Marines and naval forces. You had the special operation forces and Task Force Ranger there that had another kind of direct chain of command that really weren’t under Montgomery even though they were U.S. forces. It became very confusing, and in part I think caused a problem with intelligence, whose intelligence was being used, how the reporting chain went. There is a principle of war that says unity in command is desirable in any kind of conflict; it certainly was not there between U.S. and U.N. and even within the U.S. structure.

During a recent lecture to the students of the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Gen Zinni described his efforts to coordinate among the various military headquarters prior to accompanying Ambassador Oakley into Mogadishu to negotiate with Aideed for the release of CWO Durant. The general wanted to ensure that no military actions took place to compromise the Ambassador’s efforts. Despite the fact that then-LtGen Zinni coordinated with five separate commands within the theater (each of whom referred him to another), a helicopter still dropped propaganda leaflets declaring Aideed a war criminal in the middle of the negotiations. The general later discovered that this particular propaganda effort was directed by yet another command. His point was clear: you could not coordinate with a single commander in charge of all operations in the theater because no such single commander was given that authority.

There simply was no unity of command or effort in Somalia during UNOSom II. Command and control was further complicated by the fact that the U.N. lacks standardized doctrine, training, and equipment. This made coordinating the efforts of the numerous participating international militaries, as well as the 49 international agencies—including U.N. bodies, NGOs, private voluntary organizations (PVOs), and humanitarian relief organizations—exceptionally difficult. Adding to the difficulty, no effective host-nation government existed since Somalia was in a state of general anarchy. Finally, unity of command was jeopardized by U.S. attempts to operate independently outside of the UNOSom II command structure. As a result, the logistics components of USForSom were under U.N. operational control, while the QRF remained under the combatant command of USCentCom. TF Ranger operated in the theater independently of the QRF and, like the QRF, answered directly to USCentCom. Their instructions required them only to coordinate with the 10th Mountain Division “as needed.” Had there been a single commander controlling both TF Ranger and the QRF, Americans may have never seen the bodies of their dead sons dragged through the streets of Mogadishu.

Operational command was vested in Gen Hoar as CinCUSCentCom, and he must bear some responsibility for the lack of unity of effort between his two immediate subordinates in Somalia, MGs Garrison and Montgomery. Gen Hoar and his staff did not adequately integrate the operations of these two subordinate commanders. Beyond CinCUSCentCom’s initial reservations concerning TF Ranger’s deployment to Somalia, he and his staff appear not to have recognized or questioned the vulnerability of the TF and its helicopters given the Somalis’ ability to adapt to its tactics and techniques after repeated missions. Even at the tactical level, within MG Garrison’s TF Ranger itself, there were dual chains of command between Delta Force and the Rangers. It is clearly imprudent to create dual or multiple chains of command along functional lines within a single urban environment.

The UniTaf successfully met the span of control challenges through two innovations. First, they created a civil-military operations center to facilitate unity of effort between the NGOs, PVOs, and the military forces. This was exceptionally important in light of the fact that many of the private relief organizations had hired local security forces from the clans dominant in their areas of operations to protect their individual efforts. Secondly, they divided the country into nine humanitarian relief sectors that facilitated both relief distribution and military areas of responsibility. Where unity of command was not feasible, Gen Hoar reinforced unity of effort by requiring liaison officers from each of the multinational contingents supporting RESTORE HOPE to report to USCentCom for coordination before dispatching their forces to the theater. As LtGen Johnston emphasized, “Unity of command can be achieved when everyone signs up to the mission and to the command relationship.”

UNOSom II, however, proved incapable of exploiting the advantages of these arrangements as the scope of the mission expanded. Instead, U.S. impatience and U.N. resistance regarding the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Somalia compromised UNOSom II’s efforts. U.S. forces were withdrawn on schedule despite the fact that the handoff between UniTaf and UNOSom II remained incomplete. Only 30 percent of the UNOSom II staff had arrived in country by the time the mission was launched. Moreover, despite their vastly more ambitious mission, the UNOSom II and USForSom headquarters were not built around a standing, well-organized nucleus, trained and equipped to serve as a joint battle staff. (A standing Marine expeditionary force headquarters performed this function during the UniTaf operation.) Instead the USForSom staff was built largely from officers recruited from Army commands worldwide who had never before trained together as a battle staff.

MG Montgomery addressed the unity of purpose problems among the UNOSom II forces when he stated:

The nations didn’t all agree with the policy, and many of them were just not happy with the way the course of the mission was going. …Gen Bir could not turn to the Italian commander or the French commander, or somebody and give him a mission and expect that it would be done. It doesn’t happen in a U.N. context.

As it was, the QRF commander, MG Montgomery, had to negotiate with hesitant Malaysian and Pakistani forces for armored support while TF Ranger was trapped in Mogadishu. Documented accounts of the Italian contingent commander opening separate negotiations with Aideed, with the full approval of his home government, serve as a case in point concerning the unity of effort problems among U.N. forces. When the U.N. requested that this officer be relieved of command for insubordination, the Italian Government refused. The Somalis fully recognized the lack of unity of command and effort among the UNOSom II forces and sought to exploit it. One of Aideed’s militia commanders in Mogadishu stated in an interview that:

What we did is to concentrate our attacks on the Americans, and the forces who were taking their order(s) directly from the Americans, such as the Pakistanis. And we had some understanding with the other forces not to attack us and that we would not attack them.

Following TF Ranger’s catastrophic mission in Mogadishu, the command structure was complicated even more with the creation of a new Joint Task Force (JTF) Somalia. USCentCom designed this JTF to protect American forces while facilitating their complete withdrawal. JTF Somalia came under the operational control of USCentCom, but fell under the tactical control of USForSom. While the JTF headquarters was formed around the Army’s 10th Mountain Division, that unit lacked the staff structure needed to support joint operations. To further complicate matters, neither the JTF nor USForSom controlled the naval forces that remained under USCentCom’s operational control. The American experience in Somalia, therefore, suggests the need for standing JTF headquarters specifically trained to facilitate operational control of joint forces in complex environments. Arguably, campaigns that include urban operations are always complex.

The lack of operational communications infrastructure in Mogadishu and elsewhere in Somalia caused the operational commanders to rely extensively on satellite communications as a means of control. There was never enough equipment to facilitate this effort given the inordinate number of headquarters. Moreover, MG Garrison and his staff did not tailor TF Ranger’s communications architecture to facilitate decentralized execution. Employing the joint operations center as an intermediary between the P–3 giving directions overhead and the ground reaction force convoy, for example, significantly contributed to the confusion that prevented the convoy from successfully maneuvering to the crash sites. The intensity and tempo of urban operations demand a flattened communications architecture that maximizes lateral force communications without depending on retransmission at each level of the traditional chain of command.

Finally, the ROE, among the most useful command and control measures in urban military operations other than war, were unrealistic in Mogadishu. Logically, the soldiers on the ground violated the ROE in order to survive. Operational planners who understand the Somali culture should have recognized the potential for the SNA to use the women and children as shields. Accordingly, they should have avoided entering the densely populated Bakara Market district with such restrictive ROE. As legitimacy was a concern (in fact, it should have been more of a concern), TF Ranger should have employed non-lethal weapons, to include riot control gas, as an alternative to killing innocent civilians or dying themselves. In this case, the operational commander was responsible for making such weapons and munitions available and encouraging their use.

Intelligence

The nature of the mission in Somalia initially complicated identifying a single threat, thereby creating a focus of effort dilemma for the intelligence architecture. As is typical in urban environments, HumInt served as the most timely and useful collection resource during the campaign. Unfortunately, because no reliable U.S. HumInt network existed in Somalia prior to the operation, much of the information had to be obtained through the bribery of largely unknown sources. Thus, its reliability was always in question. In these instances, it is critical to verify the information via multiple sources. Additionally, the operational commander must coordinate between his joint and coalition forces as well as the PVOs and NGOs in his area of operations in order to ensure consistent policies for dealing with local informants. In Somalia, units from several different nations rotated responsibility for specific geographical areas, and the means used to garner information differed among the various units. Some armies paid local nationals for information. Later, when a less wealthy unit assumed responsibility for the area, the locals became vindictive when they were not offered the same bribe.

The best HumInt sources were the gang leaders themselves. The UniTaf met on a regular basis with Aideed and other clan leaders. As LtGen Johnston stated:

You may not like the characters you have to deal with but you are better able to uncover their motives and intentions if you keep a communications link open.

UNOSom II and USForSom, on the other hand, abandoned all interaction with the Habr Gidr once the manhunt for Aideed began.

The unreliability of HumInt sources among the Somali populace contributed significantly to the most obvious intelligence failure—the inability of the U.S. and U.N. forces to locate Aideed. The initial plan for TF Ranger’s mission called for the Central Intelligence Agency’s lead Somali spy to present Aideed with a hand-carved cane containing a hidden homing beacon as a gift. This plan ended when the spy shot and killed himself while playing Russian roulette. TF Ranger and UNOSom II intelligence sections also significantly underestimated the quantity of rounds in Aideed’s RPG stockpiles, possibly influencing the commander’s decision to keep the helicopters loitering in the target area. A serious shortage of people proficient in the Somali language in the U.N. and U.S. forces further complicated the effort to gather HumInt. Especially troubling is that the HumInt effort apparently did not warn the commander about the dramatic change in the perceived legitimacy of U.S. forces among the Mogadishu populace.

Collection via signals intelligence (SigInt) was severely hampered by the fact that the Somalis are not a technology dependent society. Upon learning that U.S. forces were monitoring his communications transmissions, Aideed effectively thwarted U.S. SigInt collection by merely turning off his radios. He relied on messengers, again taking advantage of the U.S. HumInt failure. Well-trained, but high-technology dependent U.S. forces were confounded by a foe with absolutely no technological tools of his own. You cannot jam or intercept enemy communications without an inside HumInt resource when his communications system is word of mouth.

The multiple and confused command structures in Somalia severely inhibited intelligence dissemination. Although USCentCom established an intelligence support element to facilitate dissemination of information gathered from U.S. sources, protection of those sources necessitated several filters before the information could be shared with other U.N. forces. The lack of communications infrastructure in Somalia further complicated dissemination from USCentCom headquarters to the theater with all of the links relying on limited satellite communications.

Nonetheless, intelligence was not a complete U.S./U.N. failure. The UniTaf used aerial photography of the authorized weapon storage sites to inventory them and ensure that Aideed and other warlords were not withdrawing weapons from them. Although maps were initially outdated or available only in scales inappropriate to urban fighting, satellite imagery and aerial photography rapidly remedied the problem. TF Ranger planned their raid on instant photomaps relayed from the aerial observation platforms. Timely intelligence on the port facilities in Mogadishu also greatly facilitated the initial employment of maritime prepositioned shipping.

Far and away, the chief intelligence failure lay in the inability of some operational commanders to appreciate the nuances of the Somali culture. While this knowledge was available, and used extensively during the UniTaf phase, ADM Howe and MG Garrison chose to ignore it. According to Gen Zinni, what the U.S. intelligence effort lacked most was:

… the ability to penetrate the faction leaders and truly understand what they were up to, or maybe [the ability to] understand the culture, the clan association affiliation, the power of the faction leaders, and maybe understanding some of the infrastructure … [that] maybe led to things like not understanding where a particular individual was, or who he was, or what his relationship was, and maybe caused mistargeting in some cases by those that were after Aideed or his lieutenants.

Thus, the greatest operational intelligence failure was one of net assessment. MG Garrison did not accurately assess the SNA’s capabilities or intent with regard to his own plan and capabilities. He underestimated the number of SNA militia and its supporters as well as its determination.

Maneuver

TF Ranger’s mission resulted in a strategic failure largely because neither USCentCom nor UNOSom II employed operational maneuver to isolate the urban objective area. TF Ranger did not have the force structure to perform this task alone. During the UniTaf phase, U.S. forces kept the Somali warlords out of the populated areas and their people disarmed. With the Americans’ hasty departure and responsibility for those areas passing to other U.N. forces and a Somali coalition, the warlords returned to the urban areas, reorganized and rearmed.

During the UniTaf mission, LtGen Johnston and Ambassador Oakley went to great lengths to shape the battlespace at the operational level to facilitate tactical maneuver. The initial combined amphibious and air assaults to seize key terrain and control the region sent a clear message and were highly effective. U.S. forces rapidly gained control of Mogadishu and the surrounding area and forced the major factions into a cease-fire. Recognizing the primacy of the clan, Ambassador Oakley and LtGen Johnston then actively engaged the clan leaders and openly advised them of when they would conduct tactical missions and for what purpose. When conducting armory inspections, for example, the UniTaf advised the clan leaders of the time and place of those inspections, and then monitored the armories via SigInt to ensure the clan leaders did not remove weapons in bad faith prior to the inspection.

Conversely, during UNOSom II, U.S. operational maneuver and fires actually jeopardized their legitimacy with the Somali people. The diplomatic nature of U.N. operations required the U.N. leadership to issue a formal resolution announcing that it was their intent to arrest Aideed. This announcement forfeited one of the strongest advantages in operational maneuver—surprise. Moreover, by targeting Aideed, ADM Howe and LtGen Bir effectively took sides in the conflict, compromissing the legitimacy of the force.

Finally, TF Ranger failed to develop and execute an operational maneuver plan that protected its critical tactical vulnerability—its helicopters. Instead, they kept their most vulnerable helicopters, the MH-60 Blackhawks, loitering for 40 minutes over the target area in an orbit that was well within Somali RPG range. No crisis on the ground existed that required any more fire support than that which could have been provided by the smaller, faster, and more maneuverable AH-6s and MH-6s. TF Ranger underestimated the enemy’s ability to shoot down its helicopters even though they knew the Somalis had previously attempted to employ massed RPG fires to bring them down during earlier raids. In fact, the Somalis had succeeded in shooting down a UH-60 flying at rooftop level, and at night, just 1 week prior to the battle. Since the greatest threat to any TF Ranger mission was a scenario with multiple downed helicopters, planners should have provided ready ground reaction forces at the start of each mission. The task force’s mission failed when the second helicopter crash site was overrun. This permitted the Somalis to use the captured pilot and the dead Americans as political weapons. As a result, the news media opened what was supposed to be a covert operation to the scrutiny of the American people and the world.

Fires

Operational fires throughout the U.S. involvement in Somalia focused too greatly on lethal options and promoted Somali hostility toward U.S. forces. The UNOSom I helicopter attack on the Kismayo technical convoy and the employment of AC–130s against Aideed’s suspected locations serve as examples of how not “to win friends and influence people.” While lethal fires were somewhat balanced with a non-lethal approach during UNOSom I and the UniTaf, the lethal approach became increasingly dominant during UNOSom II. The 17 June attack on an Aideed stronghold, for example, incorporated a helicopter gunship attack that killed at least 60 Somali noncombatants. U.S. forces’ overreliance on firepower during UNOSom II alienated the Somali populace and forfeited the perceived legitimacy of the U.S. presence. In the densely populated urban confines of Mogadishu, UNOSom II lived by lethal fires and it died by lethal fires.

Because ADM Howe and LtGen Bir largely discounted information operations, they did not establish significant public affairs and psychological operations (PsyOp) initiatives. U.S. forces participating in UNOSom II lacked a public affairs organization altogether. In contrast, the UniTaf countered Aideed’s own PsyOp campaign, which he conducted primarily through Radio Aideed, by creating its own radio station. This technique proved so effective that Aideed called MajGen Zinni over to his house on several occasions to complain about the UniTaf radio broadcasts. MajGen Zinni responded that “if he didn’t like what we said on the radio station, he ought to think about his radio station and we could mutually agree to lower the rhetoric.” This technique worked. ADM Howe’s technique of shutting Aideed’s radio station down did not. The warlords had both the weapons and the popular support. Thus, the U.N. would have been better served by making them the target of an information campaign as the UniTaf had done.

Logistics

Despite other failings during U.S. operations in Somalia, the U.S. logistics effort was well executed. This was a significant achievement, since the infrastructure within the country was almost completely destroyed and the logistics environment was exceptionally austere. This is typical of most Third World urban areas to which U.S. forces can expect to deploy in the future. U.S. and U.N. forces had to transport virtually all of their materiel support into the country by sealift or airlift. During Operation RESTORE HOPE, military and commercial aircraft moved more than 33,000 passengers and over 32,000 short tons of cargo into Somalia in 986 airlift missions. Additionally, 11 ships moved 365,000 measurement tons of cargo, 14 million gallons of fuel, and 1,192 sustainment supply containers into the country. Receiving these supplies required U.N. forces to rebuild and repair airfields and ports. Finally, the humanitarian mission required U.N. forces to use extensive wheeled transport assets to distribute the supplies to both the populace and friendly forces along difficult internal LOC. Security along these LOC necessitated the diversion of troops from other responsibilities. Finally, given the lack of adequate port facilities, Marine Corps maritime prepositioned shipping proved invaluable in bringing essential supplies and equipment ashore early in the deployment.

While very successful, the logistics effort in Somalia should not be viewed as flawless. A number of “hiccups” were experienced. The excessive drafts of Army prepositioned ships, for example, made it impossible for them to enter Mogadishu’s shallow harbor. Additionally, the weather impeded their attempts to offload supplies “in stream.” The logistics effort was also complicated by international and inter-Service rivalries. This could have been eased by a more efficient operational command and control structure. U.S. forces should anticipate special logistics challenges unique to operating with or within the U.N. One unit after-action report described the U.N. procurement system as “cumbersome, inefficient, and not suited to effectively support operations in an austere environment.”

Force Protection

U.S. forces relied far too heavily on lethal fires for force protection in an environment where maintaining perceived legitimacy was critical to mission accomplishment. Instead of moving about Mogadishu in an effort to promote relations and keep in touch with the attitudes of the local populace—as was the case during the UniTaf phase and with several other national military units within the U.N. force—U.S. forces during UNOSom II adopted a siege mentality. As a result, they lost the support of the Somali populace and effectively turned themselves into the enemy.

Despite the American forces’ unwillingness to leave their base in Mogadishu without assuming an aggressive and provocative posture, the base was poorly protected. Open to public view and with Somali contractors moving freely about the premises, the American base was an operational security nightmare. Somalis had a clear view, day and night, of U.S. forces in their hangar barracks. The U.S. billets were subjected to routine mortar strikes from the SNA. Whenever they would prepare for a mission, the word would go out throughout the city that TF Ranger was preparing to move. During an interview with PBS’ Frontline, Capt Haad, a sector commander for Aideed’s militia in Mogadishu, said of TF Ranger’s mission, “As soon as the aircrafts (sic) took off from the air bases we immediately knew.” He also pointed out that they knew when and where U.S. forces landed:

We knew that immediately after their arrival because we were in all the places where they would have arrived, say in the port, airport, the American compound, some people of us were always there, and the minute they arrived we knew that they were there.

Some evidence suggests that the Italians of the U.N. force also warned the Somalis of U.S. troop movements. MG Garrison’s failure to provide an armored, rapid reaction force capable of immediately moving to reinforce TF Ranger and a second airborne rescue and recovery crew, in the event that the first crew was lost, proved to be additional serious errors in operational force protection.

Rampant disease was also a force protection concern in Somalia and one that U.S. forces can expect to encounter in most Third World urban environments. American servicemembers were constantly exposed to the sick and dying. When U.N. forces operated earthmoving equipment to repair the infrastructure in and around Mogadishu, tuberculosis spores that lay dormant in the soil were released into the air. Medical intelligence and preventive immunizations are vitally important in these locales.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

U.S. operations in Somalia provide a clear example of how “thin” the operational level can become while battling urban guerrillas. During UNOSom II, special operations forces were employed tactically, in an urban environment, to achieve a strategic objective (seizing Aideed) in a single decisive action. This operation failed because U.S. commanders did not establish favorable operational conditions prior to committing those tactical forces. U.S. involvement in Somalia further illustrates the limitations of both military force and of the U.N. in managing ethnic urban conflicts. In the immediate post-Cold War era, the world deceived itself into believing that the U.N. could become more decisively involved than was actually possible. Until structures are created within U.N. military forces that afford a far greater degree of unity of effort and command, Chapter VII peace enforcement operations—particularly in urban environments—will continue to be difficult if not impossible.

One should be careful, though, in drawing lessons from this conflict. First, it would be wrong to look upon the military as a completely ineffective tool in such environments. When used as a complement to other elements of national and international power, the military can be productive in these circumstances. These elements, however, must be well coordinated. In Somalia, they were not. Second, there is a danger that tactical force protection measures will inadvertently outweigh strategic and operational mission accomplishment. This very tendency contributed to the U.S. failure in Somalia. The best form of force protection is shaping the battlespace at the operational level. Relying extensively on lethal fires and entering urban areas in a provocative manner cost more than they gain if they alienate the populace. Finally, despite Congress’ initial assumption, recent evidence seems to indicate that American resolve for capturing Aideed in hopes of bringing peace to Somalia was stronger rather than weaker after viewing the images of American soldiers being mutilated. As Gen Zinni has stated:

The lesson and the effect as it relates to casualties isn’t that the Americans can’t take casualties … it’s they can’t take casualties for causes and reasons that aren’t understood and clearly laid out before you get in.

The Battle of Mogadishu and U.S. operations in Somalia overall suggest several operational considerations for urban areas. The Somalia experience reemphasized several lessons learned in Hue, among them, the importance of crafting suitable ROE and of maneuvering to isolate the urban area. The Somalia experience also suggests the following additional considerations:

• dhering to the principle of unity of command is critical to success in urban conflicts. Where unity of command cannot be established between different agencies (U.N. bodies, NGOs, PVOs, etc.), the operational commander must make special arrangements to ensure unity of effort. These arrangements may range from regular coordination meetings to the establishment of a civil-military operations center. In all cases, tactical operations must be thoroughly coordinated among all operational commanders.

• JTF headquarters formed to execute missions that include urban operations should, at a minimum, be formed around cohesive, standing Service component staffs. The complexity of urban operations suggests the need for standing JTF headquarters.

• The communications architecture for operations within cities should facilitate the direct transfer of information from supporting forces to the decentralized tactical forces on the streets, without successive transmissions through the chain of command.

• Consistent with the U.S. experience in Hue, HumInt was the most effective collection means within the urban areas of Somalia. The nontechnical nature of the Somali clans severely restricted the value of other collection means. Methods used to recruit HumInt collectors from local urban populations should be consistent among all forces in the coalition. To do otherwise can compromise the legitimacy of one or more of the forces involved. In cases of urban ethnic conflict, maintaining open communications links with faction leaders involved in the dispute can be the most important HumInt source. • ultural assessment is a critical step in the intelligence preparation of the urban battlespace. Often, it will disclose enemy critical vulnerabilities or means to influence the actions of the noncombatant populace.

• Maintaining the support or neutrality of the noncombatant population is critical to success in urban fighting. The operational commander and staff must keep this in mind when planning both operational and tactical fires.

• Non-lethal fires, to include information operations, are important means of separating the adversary from noncombatants without creating casualties among the latter. Non-lethal weapons and munitions can make ROE more flexible, giving tactical forces an option between compromising legitimacy and accepting unreasonable risk. Civil affairs and media campaign plans can be vitally important to shaping conditions for tactical success in the urban battlespace. Likewise, PsyOp can effectively and favorably influence the actions of the noncombatant populace.

• Third World urban areas, with poor infrastructure, present enormous logistical challenges to U.S. forces. Strategic and operational lift as well as procurement systems must accommodate combatant and civilian needs well beyond those in other environments.

>Editor’s Note: This article is the second case study from Maj Cooling’s treatise on MOUT written when he attended the Marine Corps Command and Staff College in 1999–2000.