Millennials Merging

By: 1Posted on August 16,2019

Article Date Sep 01, 2006

by LtCol Wayne A. Sinclair

‘The human heart is the starting point in all matters pertaining to war.’

-Frederick the Great

If war is truly a young man’s occupation, then the tactical struggle to bring order and stability to Afghanistan and Iraq certainly depends on an admired but little understood generation of Americans. In a war that transforms totalitarian societies and rebuilds failed states, great discernment, adaptability, and virtue are especially essential in its junior participants. Understandably, when older Americans consider the complexities of counterinsurgency operations and the delicate nature of cross-cultural communications in the global war on terrorism, many privately wonder how such a seemingly naïve and insulated population is faring so well. Research on the character of America’s youngest generation offers some reassuring answers. America’s youth may actually be better prepared to prevail in the irregular conflicts of the early 21st century than any previous generation. The challenge for the two previous, and decidedly different, generations still in uniform lies in recognizing and realizing this tremendous potential. This recognition and realization takes more than sound leadership; it requires an appreciation of generational differences and the skill to turn this perspective into inspiration. America’s generation gap is further widened by a military culture that commends pragmatism and independent decisionmaking while promoting the doctrinal precepts of maneuver warfare-all conceptually inconsistent with the strengths, vulnerabilities, and leadership needs of a generation rapidly making its presence felt.

In spite of America’s fondness for quick, technology-driven results in warfare, blood and sweat-rather than machines and microchips-are proving the greater value. Yet as technology gives mankind ever greater powers, it gives men ever less significance. New operational concepts and promising material solutions attract far more high-level attention than studies on how people change or generations interact. Given the asymmetric character of the long war against terrorism, the American public’s deep-rooted faith in its uniformed citizenry is vital and must never be taken for granted. Although segments of the U.S. military have explored generational shifts for recruiting and marketing needs, the ability to connect with a new generation of young Americans may be completely overlooked.1

Generations

They are known as “Millennials“-the first generation to reach adulthood in the new millennium. This American cohort-born between 1981 and 2002-has other names and like-aged counterparts around the world: the Net Generation, Generation Y, the Google Generation, and Echo-Boomers. Since the dawn of civilization, people have identified generational cycles as a force of history and the master regulators for social change.2 A generation is composed of a society-wide peer group shaped by older generations, historical events, and shared experiences. It is considered as the average period between the birth of parents and the birth of their offspring-about 21 years. Within a common culture, pivotal historical events (e.g., the Pearl Harbor attack, the Cuban missile crisis, the Challenger explosion, the 11 September 2001 attacks, etc.) affect and shape different age groups’ outward and inward perceptions differently and inspire collective behaviors toward common goals.

Generational identities are also formed by the preceding generations based on what phase of life they are in, their own unique characteristics, and their intergenerational relationships. Since the exact birth dates of American generations are subjective and there is no formal naming convention per se, it is best to think of these timespans as eras. That said, the common names and approximate birth years of the six living generations of Americans are listed below:

* The GI (Government Issue) or Veterans Generation (1901-24).

* The Silent Generation or Traditionalists (1925-42).

* The Baby Boomers (1943-60).

* Generation X or the 13th Generation (1961-81).

* The Millennials (1982-2001).

* The Homeland Generation (2002-?).

Since generations are made up of people, they have many of the same characteristics. Collectively, generations have prevailing moods, temperaments, personalities and, most importantly, a distinct sense of direction and purpose. For Millennials, a brief look at their origins and traits reveals some potential strengths and weaknesses in modern war. First, however, the stage must be set by an overview of maneuver warfare doctrine and why it appeals to every serving generation except the Millennials.

Maneuver Warfare and the Human Dimension

Maneuver warfare has served as the philosophical basis for the Marine Corps’ approach to warfighting for nearly 20 years and is the cornerstone of the Marine Corps’ future concept, expeditionary maneuver warfare.3 As crafted in Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting (the watershed booklet first published in 1989), maneuver warfare begins with a thought process that stresses how, not what, to think. Accordingly, it is intended to exist not so much in prescriptive formulas or methodologies but in the minds of all Marines, where it guides their actions across the spectrum of conflict at all levels of war.4

Beginning in the mid-1970s, post-Vietnam hand wringing over the condition of the U.S. Armed Forces fueled intense debate about the American way of war. Military reformers in and out of uniform placed much of the blame on America’s “fire-power and attrition” style of warfare. Faced with the monolithic Soviet threat, and inspired by the stunning Israeli victories fighting out-numbered against Egypt and Syria in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, they sought less direct approaches to battle that promised quicker victories at lower costs using psychology as a principal defeat mechanism.5 Both linear and methodical battle reflected the prevailing military culture of order. In contrast, the principal goal of maneuver warfare is speed-at the expense of order and control if necessary-in order to make faster decisions, gain positional advantage, and leverage chaos* on the battlefield.6 In execution, this becomes what is known as tempo.

A great deal of this all-important tempo is generated by decentralized decisionmaking. Through “mission-type” orders and adept handling of “surfaces and gaps,” maneuver warfare draws its power mainly from opportunism-the calculated risk-and the exploitation of both chance and circumstances.7 Flexibility, creativity, and initiative are not just desirable in junior leaders; they are indispensable. Today, all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces embrace the precepts of maneuver warfare, and it remains the doctrinal cornerstone of the Marine Corps’ professional military education system.

* Indicative of the maneuverist mindset, “Chaos” was the radio call sign of MajGen James N. Mattis, Commanding General, 1st Marine Division during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM I.

Enter the Millennials

As a whole, the general direction of Millennials is surprising many members of the typically cynical Generation X and materialistic Baby Boomers. Millennials appear to be a more civic minded, morally grounded, and selfless generation than any in the past 40 years-maybe even longer.8 They are reversing a vast array of negative youth trends from criminal activity to drug use, from teen pregnancies and abortion to test scores and future goals.

What accounts for this change? Research suggests that a primary factor in the development of generational cycles is the oscillation between the overprotection and underprotection of children.9 While dual-career or single parents raised the “latchkey” kids of Generation X, Millennials began arriving when childbearing and rearing became a national priority once again. Childfriendly minivans with “baby on board” signs became the fashion, abortion and divorce rates ebbed, the socioeconomic tide rose, birth rates soared (at about 76 million, they are twice the size of Generation X), child abuse prevention and safety were hot topics, and several books that taught virtues and values to children became bestsellers.10 For many parents, educators, and lawyers, the goal became not to prepare children for life’s risks, but to remove as many risks as possible. By design and with the best intentions, Millennials became the most protected generation in history.11

Public education was a major influence on Millennial development and serves as the dividing line between Generation X and the Millennials.12 The reason was national school reform. After almost two decades of decline in their children’s elementary and high schools, Americans had had enough. Parent and teacher frustration with poor student performance, a lack of classroom order, and substandard public education resources led to massive school reforms during the second half of the 1980s. Changes were everywhere as parents became passionate about their kids’ education. Higher academic standards, “zero tolerance” policies, school uniforms, and formalized teacher accountability were widely instituted. By the mid-1990s, U.S. public education had moved from an “age of lament” to an “age of accountability. “13

With Millennial parents so highly invested in their children’s goals and outcomes, any sign of mediocrity in their children is met with professional “coaching” (not counseling-even the best have coaches) or expert advice. In contrast to Generation Xers, parental relationships and opinion are considered crucial to young people’s well-being and decisionmaking calculus. Accustomed to center stage, they are more than willing to work hard to meet the high expectations of the audience. For many, life revolves around organized activities. As the most over-scheduled generation in history, Millennials thrive in a multitask environment.14 To help cope with demanding schedules, technology is an enabler on a scale never before imagined. They expect light speed and interactive communications tools and are comfortable conveying and receiving information in sound bytes and cryptic keystrokes. When one considers that Millennials have never known life without cell phones, instant messaging, and fingertip access to ideas and information from around the world through the Internet, their conceptions of time, communications, and space are easier to understand.

Millennials and Maneuver Warfare

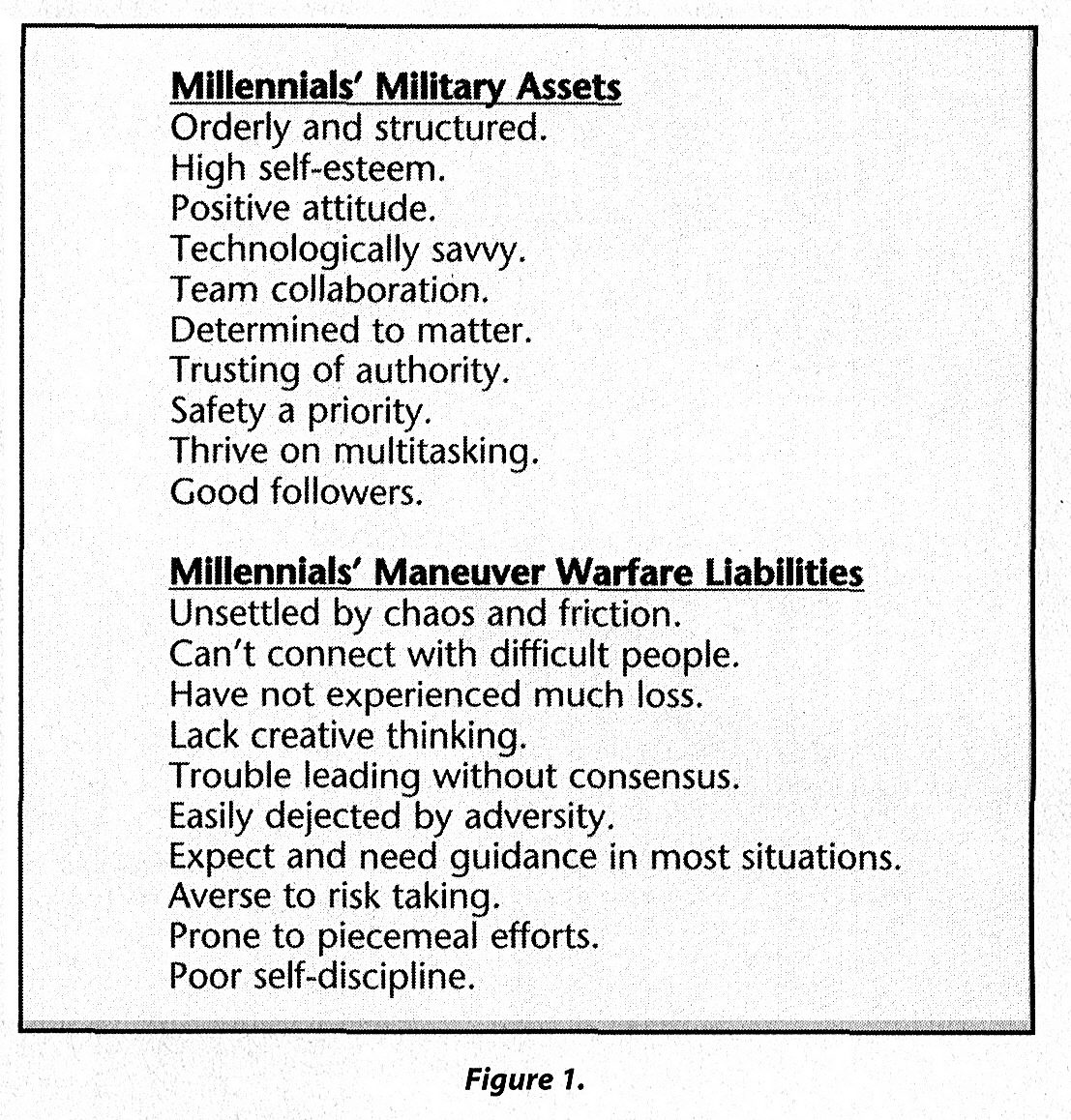

As Millennials mature, distinct traits, core values, and groupthink characteristics solidify and can be linked to positive military virtues. There is a flip side however; these much-admired assets imply expectations and propensities that can have troubling implications for many tenets of maneuver warfare. They are contrasted in Figure 1.

So are Millennials inherently better suited for methodical battle than maneuver warfare? With Generation Xers most known for self-reliance, pragmatism, and go-for-broke risk taking-tailormade characteristics for the maneuverist mindset-one may conclude that the basic concepts of maneuver warfare have a distinct generational bias. Furthermore, Millennials inherent qualities appear to have special contemporary value. Generation X decisionmakers who “just want the facts”-preferably the “bottom line up front”-to find the right “decisive” action or high-value target to accomplish the mission or destroy an enemy’s will to resist would do well to take advantage of the more introspective nature of their young warriors. Their generational propensity to impose order, seek the greater good, take the role of protector vice conqueror, build structure, and seek clarity of direction or consensus in their actions are not necessarily liabilities in the irregular three block wars and nation-building predicaments in which Marines will find themselves for decades to come. Still, one must understand their capacity for creativity and self-regulation. In contrast to their more independently minded Generation X predecessors, the Millennial small unit leaders need and expect tailored solutions (e.g., tactics, techniques, and procedures), structure, oversight, teamwork, methodology, and a cause that gives them the opportunity to make a difference for something greater than themselves. Given these ingredients, they will show a willingness to fight and, if necessary, a readiness to die that will shatter even the most negative stereotypes assigned to young Americans.

Bridging the Gap: Leading and Mentoring Millennials

Millennials look to their leaders to create an environment that respects individuals yet promotes collaborative problem solving. Hence, organizational climate is as important as organizational culture. Whereas military culture represents the sum of ingrained values and pursuits, a command’s climate develops the members’ attitudes and perceptions with respect to human interaction in several key areas: leader engagement, group cohesion, trust and respect for individuals, ethical behavior, and fair recognition for good performance.15 Millennials are not enamored by position or title. They count on experienced hands-on leaders who earn their respect by recognizing their potential and teaching them by showing them how to increase their performance. They yearn for open communications and the mentor imposed “reality check” through unembellished but entertaining “war stories” of real life challenges that focus not on a leader’s skill or stamina but on what was accomplished and learned.

In doing so, leaders must recognize that for many Millennials, sheltered affluence, communications technology, and a lifelong conditioning to virtual reality have dulled their responsiveness to the “sit and listen” lecture style of teaching. Not surprisingly, Millennials prize practical experience and the chance to “take the wheel” and learn by trial and error. Since Millennials are accustomed to structure, direction, explanations, protection, and engagement, the importance of mentoring cannot be overstressed. To this end, mentoring in a coach/partner role should seek to:

* Explain why and how things must be done-at least initially.

* Establish boundaries of conduct and behavior explicitly.

* Clarify the value of their roles in any venture. (Perceived “busy work” is despised.)

* Enforce accountability to standards through peer mentoring.

* Show how opportunism and risk taking can be balanced.

* Teach self-assessment techniques (answers truthfully, “How am I doing?”).

* Teach project and time management to include sequencing of implicit tasks.

* Provide frequent and accurate feedback in a small, interactive group.

This style serves to offset their “blindspots” and develops their decisionmaking skills before entering the chaotic environment of combat.

Finally, Millennials are exceptionally attuned to sincerity in their leaders. Leaders perceived to promote an image to intimidate, gain acceptance, or to compromise their moral authority will be suspected of fraud regardless of their levels of competence.16 Millennials may forgive many shortcomings in their leaders, but hypocrisy is the unpardonable sin.

Conclusion

As in the past, careful investments in the Marine Corps’ human capital will continue to pay the highest dividends in war. While human nature remains much the same, human behavior changes with values. In order to leverage the many qualities of the Millennial Generation, military leaders must successfully merge the best of the past with the requirements of the future.17 With three generations of Americans in uniform today, the United States is engaged in a war-predicted to last a generation-that will continue to place extraordinary demands on the character and capabilities of its servicemen and women. In a few years, virtually every company grade officer and noncommissioned officer will be a mature Millennial who entered service after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. These will be America’s “strategic” corporals and captains. They will fight and win the long and arduous campaigns of this war. The mandate for leaders at all levels is clear. For the Nation to be assured that its rising generation will be the country’s greatest source of military strength in its hour of need, they need only leaders prepared to show them the way.

Notes

1. The Marine Corps Recruiting Command began to focus on understanding Millennials for marketing purposes in 1999. Other U.S. recruiting services have since followed suit. Apart from recruiting and a presentation given to newly selected Marine Corps general officers, I can find no evidence that the newest American generation has been officially recognized by the military. Regarding how they should be trained or led (compared to past generations), numerous requests to military training organizations went unanswered, or in two cases, they replied that they were not informed on the matter. Requests for official positions or informal opinions on this topic were sent electronically to members of the Marine Corps Training and Education Command, the U.S. Military Academy, the U.S. Naval Academy, the Citadel, and the Virginia Military Institute.

2. Strauss, William and Neil Howe, The Fourth Turning, Broadway Books, New York, 1997, p. 58.

3. Expeditionary Maneuver Warfare: Capstone Marine Corps Concept Handbook, Department of the Navy, Washington, DC, November 2001, p. 5.

4. Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC, June 1997, p. 96.

5. Bolger, Daniel, “Maneuver Warfare Reconsidered,” in Maneuver Warfare: An Anthology, ed. Richard D. Hooker, Presidio Press, Novato, CA, 1993, pp. 1, 21.

6. Fleet Marine Force Manual 1, Warfighting, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 6 March 1989, p. 1.

7. Antal, John F., “Thoughts About Maneuver Warfare,” in Maneuver Warfare: An Anthology, p. 64.

8. Strauss, William and Neil Howe, Millennials Rising, Vintage Books, New York, 2000, p. 19.

9. Strauss and Howe, The Fourth Turning, p. 82.

10. William Bennett’s Children’s Book of Virtues published in 1995 is one such example.

11. Howard, Philip, The Lost Art of Drawing the Line, Random House, New York, 2001, p. 65.

12. Strauss and Howe, Millennials Rising, p. 145.

13. Toch, Thomas, “Outstanding High Schools,” U.S. News and World Report, 18 January 1999, p. 48.

14. Phalen, Kathleen, “Teaching in a Millennial World,” Virginia Education, Fall 2002, available at <http://www.itc.virginia. edu>, accessed 20 November 2003.

15. Fortune, Dan, “Commanding the Net Generation,” Australian Army Journal, December 2003, p. 105.

16. “Culture and Generational Change,” Chatanooga Resource Foundation, available at <http://www.resourcefoundation.org>, accessed 5 January 2004.

17. Fortune, p. 108.