I Didn’t Sign Up for This

By: Maj Mark Thomas and Maj Erin MalapitPosted on June 15,2025

Article Date 01/07/2025

Civilian contractors in combat at Wake Island

To compete globally in the 21st century, the U.S. military must rely on civilian contractors to manage vital logistical systems. However, war does not discriminate between uniformed combatants and civilians. This tragic fact became all too real for the Marines and construction contractors on Wake Island in December 1941. The Battle of Wake Island offers valuable operational and legal lessons for civilian contractors in combat scenarios.

At the outset of World War II, Wake Island was occupied by the understrength 1st Marine Defense Battalion, 46 Pan American (Pan Am) Airline employees operating the commercial runway, and 1,145 engineers contracted by the Navy to develop Wake into an advanced base.1 Hours after Pearl Harbor was attacked—2,000 miles to the East—the first Japanese bombs fell onto the tiny atoll of Wake.2 After two weeks of aerial and naval bombardment, the Japanese finally captured the island on their second amphibious assault.3 The defenders of Wake fought heroically, inflicting over 1,000 casualties, sinking two destroyers, damaging eight other ships, and downing 21 aircraft. The 1942 movie, Wake Island, memorialized the heroism of the Marines but downplayed the role of the civilians.4 However, dozens of civilian volunteers assisted the Marines in preparing defenses and directly engaged the Japanese in combat. Several Marine officers even recommended their attached civilian volunteers for decoration.5

This article examines how the civilians were incorporated into the defense of Wake Island. First, it will examine the command relationship between the Navy and contractors, then analyze how the Marines incorporated the civilians into the fighting, review legal considerations, and recommend lessons learned for contemporary military leaders. These lessons are: Account for combat situations in contracts, incorporate local contractors into combat contingency planning, and educate contractors on how the Law of Armed Conflict affects them.

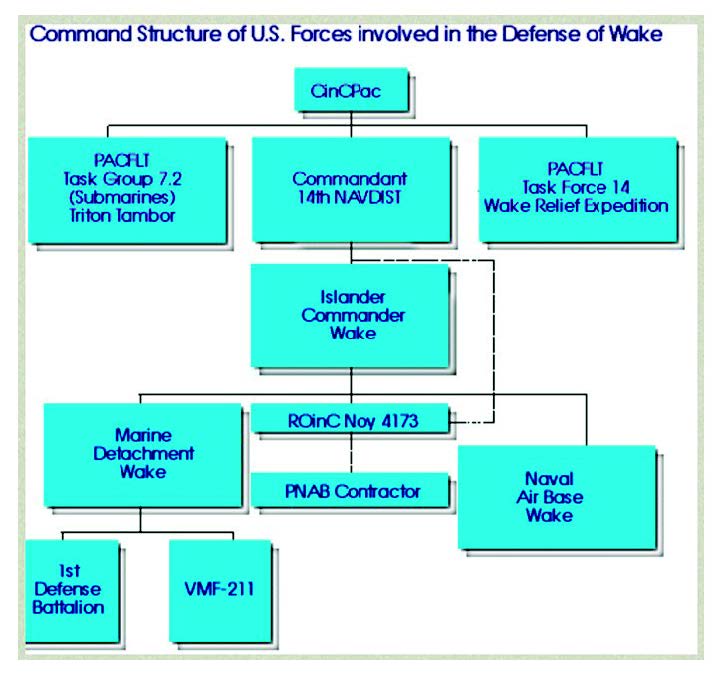

Military-Civilian Relationship on Wake

The Marines and civilians on Wake Island had functionally and legally unique, segregated roles. The first group to permanently occupy Wake was employees of the Pan American commercial airline, which used the atoll as a stop for its seaplane service ferrying passengers and mail to the Philippines. Although Pan Am had Navy approval to operate from Wake, the Navy exercised no control over its operations.6 After the initial assault from the Japanese on 8 December 1941, all but three of the Pan Am employees evacuated Wake on a civilian aircraft.7 The largest contingent on the island was the 1,145 civilian workers under the construction conglomerate, Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases (PNAB), who started arriving on the island in January 1941.8 While PNAB was under contract to the Department of the Navy, the engineers were only legally allowed to perform the construction work according to Contract NOy-4173, which called for the construction of a naval air station.9 As shown in Figure 1 (on the following page), the PNAB workers directly answered to a naval responsible officer-in-charge of the 14th Naval District. However, much like a modern contracting officer representative, the responsible officer-in-charge could only ensure the workers were living up to the terms of the contract, not issue them orders.10 When the Marines of the 1st Defense Battalion, commanded by Maj Devereux, arrived on 19 August 1941, they were under strict orders to keep their activities separated from the civilian workers. In fact, the PNAB civilians were even prohibited from refueling military aircraft, taxing the understrength Marine Battalion even more.11 Navy CDR W.S. Cunningham was the Wake Island commander in charge of both civilians and military personnel, but his role was more like a modern-day garrison commander. CDR Cunningham had no authority to order the civilians into combat, and Maj Devereux was in charge of the defenses overall.12 Despite this strict segregation, a looming war against Japan forced the Marines to bridge this gap.

Civilians in the Defense

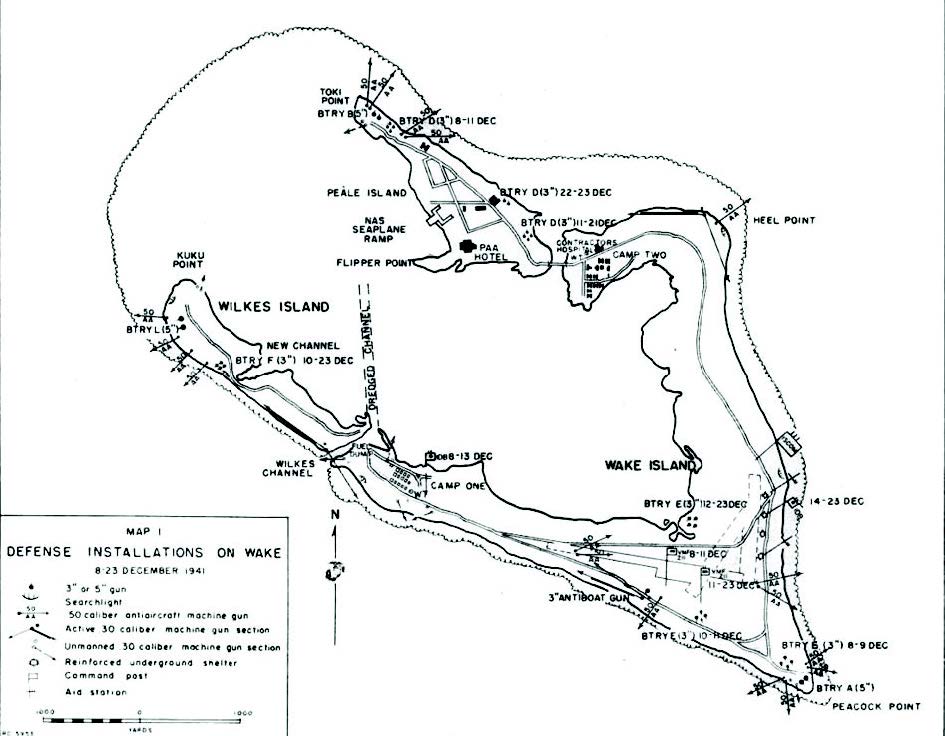

The Marines at Wake Island incorporated contractor volunteers into both non-combat and direct combat roles. Construction contractors fit more naturally into non-combat roles such as creating earthworks, aiding the wounded, and moving heavy equipment. Maj Devereux praised the efforts of the civilians in this regard, but it was too little, too late. The civilians only deviated from working on the construction stipulated in the contract after Wake was bombed.13 Aside from the more obvious engineering tasks, necessity demanded that the civilian volunteers directly engage in combat. The Marine 1st Defense Battalion only had about a third of its authorized manpower, which meant most of its heavy weapons and fighting positions did not have full crews.14 Figure 2 shows Wake’s defensive strong points and indicates unmanned weapon systems. All too aware of this shortfall, the Marines began training civilian volunteers on heavy weapons three months before the attack.15 Civilian volunteers helped to occupy some but not all of these vital strong points.16 Notably, Sgt Bowsher led an all-civilian crew of 16 volunteers on Battery D’s three-inch naval gun located on the island’s northeastern end.17 To coordinate the civilian volunteers, Maj Devereux coordinated directly with the contracting superintendent, Dan Teeters, a World War I veteran who organized requested civilian work parties.18 Often left out of posters and movies, the civilians on Wake Island who did volunteer to aid the Marines deserve just as much recognition. The Japanese certainly treated them the same.

Legal Considerations

Civilians engaging in combat alongside soldiers do so at their own legal risk. Although Japan did sign the 1929 Geneva Convention, the Japanese military became notorious for its mistreatment of prisoners.19 For a modern perspective, the currently in effect Geneva Convention III, ratified in 1949, is best for analyzing the legal status of the fighting contractors on Wake. Geneva Convention III stipulates that civilians accompanying combat forces, such as civil engineers, enjoy the same prisoner of war (POW) status as soldiers. This distinction is important because POWs are entitled to extra rights, such as limits on the type of labor they perform.20 However, if the civilians decide to fight, then only certain criteria grant them POW status. Article 4 states that militias must have a clear commander, have an insignia, must carry arms openly, and must respect the laws and customs of war.21 On Wake, one could argue that the contractor volunteers constituted a militia, but they lacked an official uniform or insignia distinct from the PNAB civilians who did not want to fight. The civilians did have a right to self-defense, but if they were captured after fighting instead of immediately surrendering, then under the Geneva Convention, they would not have to be treated as POWs. Furthermore, the civilian volunteers would not have combatant immunity, meaning they could be charged with murder by the government whose territory any killing took place in. Seeing how Wake Island was a U.S. territory, not surprisingly, no civilian ever saw their day in court. Although helpful for future cases, the Japanese did not weigh these considerations. The Japanese who captured Wake Island treated (and mistreated) all the civilians, even those not participating in the defense, the same as the Marine prisoners of war.22

Conclusion

The Marines and civilian defenders of Wake Island still have lessons to teach the force today. As contractors become increasingly enmeshed with soldiers in the modern operating environment, commanders should consider how to manage or even employ them in combat situations.23 First, unlike at Wake, military contracts should have some stipulation on when and how civilians report to commanders in a combat situation. Even if the contractors cannot fight, the commander should be able to keep their accountability. Second, military units should identify which civilians would be willing to assist in combat and provide necessary training. Contingency plans also should have provisions for how the contractors are either employed or protected. Then the commander should leverage the existing civilian chain of command as much as possible. Lastly, civilian contractors should be made fully aware of the legal repercussions if they choose to fight and be provided distinct insignia if they make that resolution. It is not a decision to be taken lightly, but as the experiences of Wake proved, the alternative could be worse. Out of the 1,145 contractors on Wake Island in December 1941, 34 were killed in battle, 98 were massacred on the island in 1943, and 114 died in Japanese POW camps.24 Contractors supporting the military cannot always choose if they are suddenly in a combat zone, but they can be more prepared by those who make preparing for war their profession.

>Maj Thomas is an Army Special Forces Officer with several combat deployments to the Middle East. He recently graduated from the Marine Corps School of Advanced Warfighting and is currently serving as a Plans Officer in I Corps.

>>Maj Malapit is a Judge Advocate Officer who deployed to Latvia during her time as an Engineer Officer. She recently earned her LLM from the Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School and is currently serving as the Chief of Justice for the 7th Infantry Division.

Notes

1. Bonita Gilbert, Building for War: The Epic Saga of the Civilian Contractors and Marines of Wake Island in World War 2 (Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers, 2012); and James Devereux, Report on the Defense of Wake Island (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Archives, 1945).

2. Report on the Defense of Wake Island.

3. Ibid.

4. Devereux, The Story of Wake Island (New York: Charter, 1947).

5. Woodrow M Kessler, Battery B Report to LtCol Devereux (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Archives, 1945); and George Kinney, Report to Lt Col. Devereux (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Archives, 1945).

6. Building for War. See specifically, Chapter 2, “Opportunity Knocks.”

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. National Archives, Federal Register Volume 6, Number 21 (Washington, DC: 1941).

10. R.D. Heinl, The Defense of Wake (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, 1947).

11. Report on the Defense of Wake Island.

12. The Defense of Wake.

13. The Story of Wake Island.

14. The Defense of Wake.

15. Building for War.

16. Report on the Defense of Wake Island.

17. Building for War.

18. The Story of Wake Island.

19. Utsumi Aiko, “Japan’s World War II POW Policy: Indifference and Irresponsibility,” The Asia-Pacific Journal May 2005, https://apjjf.org/-Utsumi-Aiko/1790/article.html.

20. Final Record of the Diplomatic Conference of Geneva of 1949, Vol. I, Federal Political Department, Bern, Section III, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gciii-1949?activeTab=undefined.

21. Final Record of the Diplomatic Conference of Geneva of 1949, Vol. I, Federal Political Department, Bern, Section I, Article 4; https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gciii-1949?activeTab=undefined.

22. Building for War.

23. Mark F. Cancian, U.S. Military Forces in FY 2020: SOF, Civilians, Contractors, and Nukes (Washington, DC: CSIS, 2019).

24. Building for War. See specifically Appendix II.