Gendarmerie de Marjah

By: Maj Mathew K. LesnowiczPosted on September 15,2025

Article Date 15/09/2025

Success at ground level

Marjah, Afghanistan, was the financial base and perceived Taliban “heart of darkness” prior to Operation MOSHTARAK in early 2010.1 After a few months, the political perception of the progress of MOSHTARAK was that the reclaiming of Marjah for the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) was moving too slow. The former Commander, International Security Assistance Force, GEN Stanley McChrystal, USA, even referred to Marjah as a “bleeding ulcer.”2 Marjah needed a turning point, and one manifested in the combined efforts of Marines, the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), and, most importantly, grassroots security initiatives. This article seeks to capture the value and success of grassroots security initiatives in Marjah district in early 2011.

The fledgling, unofficial district of Marjah is a heavily populated rural area estimated to be home to 150,000 to 200,000 people. The district is built around a network of irrigation canals constructed by the U.S. Agency for International Development in the 1950s and 1960s. The district was split into two battalion areas of operation (AOs). The southern area, known as “Marjah proper” or “South Marjah,” was organized in blocks created by the 1 by 3 kilometer cultivable tracts cut from the desert and traced by irrigation canals. Marjah proper was essentially already organized into 50 platoon-sized AOs. Following construction of the U.S. Agency for International Development project, Marjah became an American-style melting pot of many different Pashtun tribes that took advantage of government land offers, resulting in intermixed, heterogeneous villages. This tribal dynamic meant the people were accustomed to compromising between tribes to accomplish daily tasks such as division of water usage for their crops.

Friendly forces in Marjah consisted of 2 reinforced Marine infantry battalions (2d Battalion, 9th Marines (2/9), to be replaced by 2/8 and 3/9, to be replaced by 3/6), 2 Afghan National Army (ANA) kandaks (battalions), 2 Afghan National Civil Order Police (ANCOP) kandaks, and 1 large district Afghan Uniformed Police (AUP) force. In the fall of 2010, 2/6 (3/9’s predecessor in South Marjah), under Regimental Combat Team 7 (RCT–7), then RCT–1, began the Interim Security for Critical Infrastructure (ISCI) program. ISCI was modeled after the Combined Forces Special Operations Component Command-Afghanistan (CFSOCC-A) program known as Afghan Local Police (ALP), which was unveiled earlier in 2010. ALP, exclusively partnered with special operations forces, was a GIRoA-sanctioned grassroots security initiative. It centered on locals defending their neighborhoods against the insurgency. Before ALP could operate in a district, the site had to be approved by International Security Assistance Force Joint Command, CFSOCC-A, and the Afghan Ministry of Interior (MoI), which could take months. The authorization and approval for conventional Marine forces to wield ALP in Marjah was uncertain. ISCI was created to provide Marjah the immediate benefits of a grassroots security program. ISCI was to be a transient program until an MoI alternative could replace it. At the time of 3/9’s arrival, 2/6 had recruited and trained between 200 and 300 ISCI members. In North Marjah, 2/9 recruited and trained between 40 and 50 members.

Coalition support of policing in Marjah was distributed across several parties. The primary advisor to the District Chief of Police (DCOP) was an RCT–1 officer assigned to the district government center where the DCOP lived but did not work. In addition to the DCOP’s primary advisor, there was the South Marjah Police Advisor Team (South Marjah PAT) platoon commander based at the Marjah District Police Headquarters (Marjah DPHQ). The platoon commander also worked with the DCOP daily and was primarily concerned with AUP issues in South Marjah. The battalion in North Marjah also had a PAT platoon commander who operated from his battalion CP several kilometers to the north. He was primarily concerned with AUP, ISCI, and ANCOP issues in North Marjah. ISCI issues in South Marjah were run by that battalion’s S–3A (assistant operations officer). Amidst these distributed duties, the DCOP remained the sole Afghan official responsible for all AUP, ISCI, and ALP within the district.

Mission

The Marines of Marjah saw the counterinsurgency fight as a numbers game where we sought to achieve the highest ratio of counterinsurgent to population; however, with Marjah’s large population and threat, we could not secure it quickly with the forces provided. We decided to grow our own combat power. The mission was to recruit, man, train, equip, finance, and advise a battalion-sized element to secure the population and link it to GIRoA.

Execution

Coalition and ANSF units needed specific roles so we could develop a “combined arms” approach to securing Marjah. Marines and ANA, capable of operating in austere environments, would expand the bubble of security from the center of Marjah to the desert outskirts. ANCOP, comprised of literate former AUP NCOs, were the most developed force and were logistically independent, capable, and reliable enough to accomplish basic tactical tasks. ANCOP served as a highway patrol that secured key lines of communications. The AUP were positioned around key population centers within the security bubble. Coalition forces and ANSF units formed a series of concentric circles centered on the district government center (see Figure 1). The perimeter, key population centers, and routes were secured, but a gap existed: In the bubble, there were still huge tracts of land and small villages lacking significant presence. Grassroots security initiatives were the answer to filling this gap.

The concept was to develop a large police force of local men and then train and professionalize them so they could defend their blocks and augment security forces. The relationship between ALP, ISCI, and AUP was modeled from a typical American county in which there are municipal police, highway patrol, and a county sheriff’s office working within the same AO with different powers. For example, Los Angeles County has the California Highway Patrol, Los Angeles Police Department, and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, where all forces operate side by side and work closely together on a daily basis.

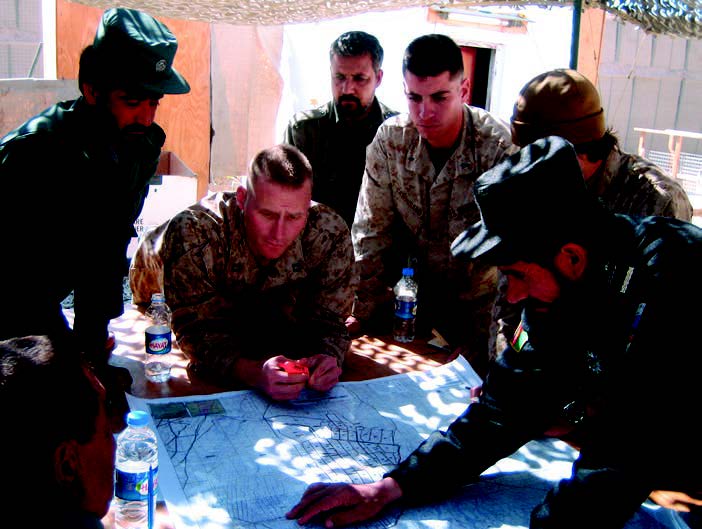

To realize our concept, we first had to reorganize our advising effort to efficiently develop the Afghans. Advisors are most effective when side by side with their partners 24/7. Marjah’s DCOP spent the preponderance of his time (daily from approximately 0600 to 2200) at his District Police Headquarters (DPHQ). He slept at the district center compound where his advisor resided. Day-to-day business was conducted at DPHQ, yet his advisor did not possess a workspace or consistent transportation to advise the DCOP during daily operations. In addition to the DCOP’s advisor, the South Marjah PAT, S–3A, and North Marjah PAT all influenced parts of the DCOP’s force. The DCOP had four different Marine officer advisors who pulled him in different directions. Most importantly, not one Marine advisor was in a position to appreciate the full responsibilities of the DCOP. The distributed advisors caused confusion and frustration on both sides of the partnership. We had success in consolidating the management of policing under the PAT. The South Marjah PAT, under the command of an RCT–1 officer, assumed control of advising the DCOP, manning, training, and equipping AUP, ISCI, and ALP. There still existed a potential fissure between the North and South Marjah PATs, but the South Marjah PAT provided a considerable amount of legwork in contracting (facilitating weapons and equipment procurement through Afghan processes) so that the relationship between PATs was mutually beneficial. As a result, the DCOP had a dedicated partner who shared the gravity of his responsibilities and became a single source for support. Afghan confusion and frustration decreased and coalition understanding of police capabilities and limitations increased. The good relationship and unity of effort between North and South Marjah PATs reinforced the AUP chain of command and forced the centralization of logistical and administrative support at the district level.

PAT organization. PAT organization was simple. The officer in charge handled engagement and advising with key Afghan leaders and issued commander’s intent. The executive officer ran the day-to-day operations of the various sections and developed courses of action for accomplishing the officer in charge’s intent. A training cell managed five training centers and issued guidance to cadres. A finance cell managed the drafting, processing, and organization of multiple contracts to finance ISCI salaries, uniforms, radios, and equipment. Administration of funding streams required several certified paying agents, purchasing officers, and project managers. An administrative cell partnered with AUP finance and personnel officers to ensure police were paid. Each member on the team held at least one collateral duty in addition to his primary mission.

We then organized the battlespace for efficiency. The PAT assisted the DCOP in dividing Marjah into four precincts. ANA, U.S. Marine Corps, ANCOP, AUP, and ALP headquarters were collocated to ease coordination and communication by key leaders.

Man. The recruiting effort was multipronged. The battalion commander down to platoon commanders saturated their conversations with ISCI recruiting messages; however, the DCOP was the pivotal recruiter, as he was crucial in recruiting block leaders. The first core group of ISCI leaders, or “White Kings,” energized recruiting by their example. A newly recruited block leader had to secure approval of his elders, which the DCOP and PAT recorded. The PAT would enter each approved member into the BAT (biometric automated toolset) system and issue an ISCI or ALP identification card. If a recruit was flagged on BAT, the DCOP and ISCI/ALP leadership would determine if he was eligible to serve. The Afghans had the final say. To build combat power fast, the PAT supported mobile registration of ISCI members and held regular registration hours at DPHQ. Within a few months we recruited over 1000 members.

Train. The PAT established and operated 5 training centers to support a 21-day MoI period of instruction for ALP. Cadres were small and included a lead instructor, translator, and an occasional assistant for practical application. Instructors levied Afghan leaders as troop handlers and in many instances, assistant instructors. Each day trainees exercised and recited a pledge of allegiance to GIRoA. Training days began early and concluded before noon so as not to disrupt farming and household business. White boards, tents, and chairs were purchased. Chairs were an important luxury; when a trainee received a chair, he felt that what he was doing was special.

Equip. We concentrated on facilitating the procurement of weapons, ammunition, uniforms, and equipment to the Marjah police. Weapons and ammunition were the most critical. An unarmed policeman was useless. Coalition forces were legally restricted from providing weapons to the police and we never violated those rules. We used the numerous weapons cache finds to our advantage. It became policy to turn over all AK–47 caliber (and below) weapons and ammunition to the DCOP. Once the DCOP possessed reclaimed weapons and ammunition, he could distribute them as he saw fit. The DCOP chose to outfit ISCI members with these weapons. The benefits of arming an ISCI member outweighed the alternative of sending caches away to be exploited as evidence. The PAT also assisted the AUP in pulling on its own supply chains to pick up weapons and ammunition from the provincial supply point in Lashkar Gah.

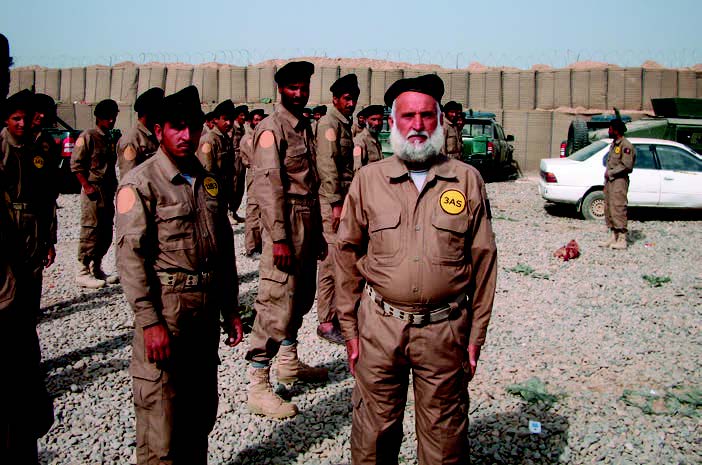

The PAT became experts at wielding the multiple funding streams present on the battlefield. Initially ISCI wore a yellow armband purchased via the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP), but it was hard to see. ISCI and ALP on the battlefield meant limited use of supporting arms since they were difficult to identify, so we outfitted them with uniforms in order to integrate supporting arms into their operations. CERP was used to purchase each member a full uniform, complete with blouse, trousers, belt, beret, boots, chest rigs, and unit patches. The DCOP designed the uniforms based on a prototype ALP uniform. The PAT used local contractors to produce and deliver all 1,200 sets of uniforms. We went to great lengths to transport the uniforms (which were made in Kabul) using both local ground and military air transportation. The PAT installed a tailor shop at DPHQ that produced 700 tactical vests on-site.

ISCI members were dependent on mobile phones for communication. Only one carrier, Afghan Wireless Communication Company, serviced Marjah. Local Afghan Wireless Communication Company towers would shut down daily at approximately 1600 to 1700, leaving no reliable means of communication until the next morning. The PAT set out to purchase GP360 Motorola VHF radios, ultimately delivering over 250 of them and working with the police to devise a basic communications plan. We laid the groundwork for the establishment of radio repeater towers to ensure reliable radio communications throughout the district. We also programmed our PRC–152 radios to talk to police radios. The improved network accelerated reaction times to enemy activity and increased command and control for the DCOP. Alerts could be transmitted quickly to tighten the noose on fleeing insurgents. Once in police hands, the radios and the communications plan took on lives of their own, and soon each leader had a call sign and a series of code words.

Finance. The most challenging task was ISCI’s financial management. CERP rules and regulations became a focal point of the PAT. A finance cell within the PAT, comprised of an officer and NCO, was solely dedicated to mastering CERP. The PAT did not receive training on USFOR-A Publication 1–06, Money as a Weapon System Afghanistan (MAAWS-A) (U.S. Forces, Afghanistan, December 2009), or the CERP, save a few classes once in theater. The cell managed the 40 to 50 simultaneous contracts as the program grew in popularity. Each contract contained roughly 16 to 20 pages of documentation. Afghan currency exchange rates would frequently fluctuate, causing on-hand cash shortages right before payday. Fluid timing for approval of new ISCI contracts would always cause instability and frustration for ISCI members. ISCI members relied on their first payday to reimburse the fuel and equipment costs accrued after weeks of standing up against the Taliban. To the enemy, a future ISCI leader waiting for contract approval was no different than an active ISCI leader. Changing interpretations of CERP rules as the scope of the ISCI program grew caused major delays.

Advising. Upon introduction to the DCOP, we met a small, frail, and quiet man in charge of a ragtag band of police. First impressions failed to reveal that the DCOP was an exceptional leader and his police had their priorities straight to fight an insurgency. The PAT advised the DCOP based on his strengths and weaknesses. As a former Mujahedeen fighter, the DCOP was a war hero. His reputation forged strong, effective relationships with key elders. The DCOP, however, was a terrible manager and lacked organization skills, a considerable problem since his responsibilities were those of a battalion commander. The DCOP would be successful if he was paired with an organized and loyal deputy. The PAT identified one of his talented, experienced officers, but the challenge was to get the DCOP to use him, as the concept of delegation in Pashtun culture equates to giving away power. The PAT persisted and began to see the DCOP delegate. The DCOP was an excellent public figure. Like an American county sheriff, he was more politician than law enforcement officer. He had the ability to recruit and mediate problems and disagreements. The PAT advised the DCOP to hold weekly ISCI meetings with district community council members and the district governor. His efforts in holding the police force together with peaceful mediation continually undermined insurgent efforts to divide ANSF in Marjah.

Considering the conditions, the police weren’t bad. Police weapons and ammunition were clean and uniforms were kept in surprisingly good condition. In fact, in some areas, the Afghans were superior to coalition forces. At the platoon level, Afghans were far faster than Marines. The Afghans were lightly armed and equipped, producing short response times. Marines—subject to their many rules and requirements to utilize complex technologies such as electronic countermeasures, radios, MRAPs, mine rollers, and optics—were very safe yet very slow when a required moving part reliably broke or malfunctioned. The police could rally and deploy a platoon-sized outfit within 20 minutes or less. In another few minutes, they could surge and completely saturate an area, which was a formidable capability from the enemy’s perspective.

Transition to ALP. The ISCI program coupled well with ALP. It could be started quickly and did not rely on slow-responding MoI institutions to finance and equip. ISCI whet the public’s appetite for grassroots security programs, but it lacked the authenticity of an MoI institution. ALP was one step closer toward the Afghan government. Once CFSOCC-A and MoI approved Marjah for ALP, we were ready to transition ISCI into ALP.

CFSOCC-A served as the executive agency of the ALP program in Afghanistan, and provided guidance on its shaping. While ALP is an armed police force, it is first and foremost a vehicle to link the people to their government. ALP must be rooted in the shura (meeting) or traditional Afghan council of elders. An ALP site first requires a village stability platform (VSP). In Marjah’s case, the VSP was the district community council.

After a validation shura in which MoI officials approved Marjah’s request for ALP, the district was approved for a 300-man tashkiel (table of organization and table of equipment). The tashkiel included 289 patrolmen, 10 platoon commanders, 1 district leader, 20 Ford Rangers, 30 Icom radios, and 300 AK–47s. The PAT recommended to the DCOP that the 300-man tashkiel be separated into three 100-man companies each to be commanded by an ALP company commander (Marjah would later receive an increase of another 100-man company and would increase to four 100-man precincts). ISCI membership was not a prerequisite to becoming an ALP officer, but the elders preferred to select ALP officers from the large existing pool of ISCI members. Each candidate had to complete the 3-week ALP period of instruction, a biometric scan, a drug test, a yearlong contract, and a taskera. A “taskera” is the Afghan national identification card proving citizenship. The PAT went through great lengths to arrange the most convenient means for ISCI members to receive a taskera. Marjah, as an unofficial district, was a special case since it lacked standard government services (specifically a district taskera office and official). The PAT had to arrange for a taskera official and the provincial recruiting officer to travel to Marjah on several occasions to issue taskera applications. While the PAT continued to train candidates as ALP officers, an MoI/CFSOCC-A in-processing team administered biometric enrollment and drug tests. Candidates were disqualified for opium use only. Marijuana use was common in Marjah. Candidates discovered using marijuana were disciplined by the DCOP and in most cases retained. Multiple infractions brought more severe punishment and severance. Once the candidates were official ALP officers, MoI supplied weapons, ammunition, uniforms, vehicles, radios, and, most important, salaries. We continued to pay ALP an ISCI salary until the government salary (which we also assisted the police with administering) kicked in. The PAT assisted the police with multiple trips to the provincial capital in Lashkar Gah to engage provincial AUP staff officers to requisition and transport ALP supplies.

Marjah’s employment of ALP differed from special operations forces–partnered ALP sites. CFSOCC-A advertised that outlying district areas were to be secured by ALP with other ANSF units securing population centers. In Marjah, outlying areas were enemy-held. The enemy was well armed and not subject to caliber restrictions on weapons as was ALP. MoI supplied ALP with 1 AK–47 and 2 magazines with 30 rounds each. They received no heavier weapons such as rocket-propelled grenades, PKMs (Kalashnikov machineguns), or 25mm grenades. We pursued caliber waivers for ALP, but, even if approved, delivery would have been subject to a slow and corrupt MoI supply system. Instead we (DCOP and Marines) employed ALP in the security bubble, in the gaps existing within the concentric circles of ANSF and coalition forces. ALP operated the same way as ISCI; their policing allowed Marines and ANA to clear and hold outlying areas.

There were many problems with the police but they all could be solved or mitigated. Rivalry between ANSF units was an early problem that took solid partnership from the entire battalion to overcome. We made it clear that the alternative to cooperation was defeat. Conflicts never completely disappeared but were seriously reduced as each ANSF unit settled into solid working relationships. ISCI and ALP were not immune to corruption, but they didn’t break any records either. The corruption levels in ISCI and ALP mirrored those of any other ANSF institutions. ISCI and ALP would break rules and need constant education on their limits of power and responsibility, but that’s precisely why we as advisors were there. Perhaps most of all was the tremendous fear of having a large armed group that would face unemployment once the insurgency was defeated. “Off-ramp” plans for ISCI and ALP involved vocational/technical schools and funneling former members into other ANSF units; however, the PAT noticed a trend of ISCI members voluntarily leaving the ranks to seek employment in the developing bazaars. ISCI was part-time work. Members provided invaluable service as local police officers, but continued to farm and earn income elsewhere. The salary for ISCI may have initially seemed like a draw, but the $150 a month wasn’t that much considering a good AK–47 (a job requirement) cost $800 to $1,000. Most ISCI members would dissolve into the emerging economy and the agricultural life they never left. It was a risky endeavor that had its fair share of problems. Arming a group of folks that didn’t always get along, with agendas that sometimes ran contrary to GIRoA, posed a challenge, but the risks never outweighed the gains.

The failure of previous grassroots security initiatives in Afghanistan, such as the Afghan National Police Auxiliary and later the Afghan Public Protection Force Program, and the memory of complications with the Sons of Iraq program, caused apprehension and, in some cases, opposition to the ISCI program. Opponents saw the program for what it seemed to be on paper: hired U.S. Government security contractors blindly selected and managed by Americans willing to pay anyone to improve security. The design and management of ISCI contained three key principles that set it apart from previous programs:

• First, the ISCI program was Afghan-led. Each block appointed its own leader along traditional lines in which elders selected and approved a man, and that leader reported to Marjah’s DCOP.

• Second, local Afghans managed the ISCI program. Afghan elders and block leaders selected each man chosen for duty in the ISCI program—no man was selected by coalition forces. The DCOP and district governor approved all block leaders and their units.

• Third, the ISCI program provided a critical link for the people to their government. ISCI leaders became elected district community council members. ISCI membership was not a prerequisite for election, but those involved in ISCI already possessed a natural inclination for community and government involvement. ISCI began to fulfill ALP objectives even before a Marjah ALP site was approved.

What Did They Bring to the Fight?

Cost effectiveness. The ISCI and ALP programs could accomplish the same tasks with a few scantly equipped men, whereas coalition forces would be forced to use expensive intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; large vehicles; fuel; and the support structure it takes to put a Marine on the ground. These brave Afghan men were not chaff, but if you look at their results compared to what it costs them to operate, it’s a very convincing argument in times of looming budget cuts.

Credibility. Of specific importance was the credibility of GIRoA’s cause to the local population. There are cultural and religious obstacles that need to be overcome for a fence-sitting local Marjah man to side with a bunch of Americans or ANA or AUP from a different province. It is easier for that same man to side with a neighbor involved in a grassroots security program.

Unique knowledge of physical and social landscapes. Local knowledge from ISCI was used to refine operations whether it was a recommendation on a safe, trafficable route or how a certain neighborhood may respond to a company helo raid in their backyard. ISCI and ALP were consistently included in operational planning. No matter what the tactical yield of the operation, if it was a scheme of maneuver endorsed by the public, it was a victory for the people and for GIRoA. Any instance where the peoples’ will could be manifested in a GIRoA operation was a critical blow to the insurgency. The people want an instrument to provide their needs and will use any instrument available, whether insurgent or legitimate government. It is imperative that the government be the most accessible and easy instrument to provide the needs of the people.

Symmetrical approach to the enemy. Fight fire with fire. The insurgents enjoyed fighting coalition forces asymmetrically. They benefitted from typical insurgent advantages: concealment and logistical support from the population. ISCI and ALP denied insurgent access to the population. An ISCI or ALP member was a “human biometric machine” who could identify insurgent members and supporters. ISCI and ALP turned the tables on the insurgents. The population was teeming with ISCI and ALP. The insurgency was now surrounded uncertainty and danger. The psychological impact was tremendous, as confirmed by reports of Taliban leadership being frustrated by the success of the ISCI and ALP. We learned that the Taliban bounty for ISCI and ALP members surpassed the price tag for an American officer.

Conclusion

The measures of effectiveness of ISCI and ALP were simple: Wherever ISCI and ALP were active, there were no significant enemy actions or events. Perhaps the most glaring measure of effectiveness came when we received reports of insurgent leaders issuing calls to prayer in Quetta, Pakistan, specifically against Marjah’s ISCI. The enemy justified the value of grassroots security initiatives. At the risk of seeming like a self-licking ice cream cone, it is important that this story be told. What we ended up building was one of the largest police forces in Afghanistan. Growing our own Afghan-owned and -operated combat power linked to GIRoA was the turning point Marjah needed. Our work was similar to that of Smedley Butler and Chesty Puller and their experiences in the Gendarmerie de Haiti. The efforts of RCT–7, RCT–1, 2/9, 2/6, 3/9, and 2/8 were in keeping with the Marine Corps’ small-wars tradition.

Notes

1. Staff, “British soldier makes ‘ultimate sacrifice’ as he dies in Afghanistan on first day of Operation Moshtarak,” Daily Mail, 13 February 2010, available at www.dailymail.co.uk.

2. Nissenbaum, Dion, “McChrystal calls Marjah a ‘bleeding ulcer’ in Afghan campaign,” McClatchy Newspapers, 24 May 2010, available at www.mcclatchydc.com.

>Originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette, February 2014. The author’s biography is available in the original edition.