Homefront Heroes: Marines Recall Lifesaving Actions During Hurricane Katrina

By: Kyle WattsPosted on August 15, 2025

The Iraq war didn’t go as planned for Jerod Murphy, but it started out the way any Marine might have hoped. He was there at the very beginning. He deployed in 2003 as the maintenance chief of 3rd Platoon (Reinforced), Company A, 4th Assault Amphibian Battalion (AABn).

Being the only active-duty member of the unit’s Inspector-Instructor (I&I) staff assigned to 3rd Platoon, Murphy felt especially responsible for the reservists who were alongside him. The amtrackers staged in Kuwait with thousands of Marines and other U.S. servicemembers massed for invasion. On March 20, the Marines finally cranked up their tracks and pushed across the border into Iraq.

Murphy’s war lasted six days. His platoon’s amphibious assault vehicles (AAVs) rolled through Nasiriyah laden with infantry, and by the 26th, battled insurgents in Al-Shatrah. Murphy stood in a cargo hatch, fighting partially exposed above the roofline of the vehicle when a bullet shattered his arm. The injury required evacuation back to the States, where Murphy begrudgingly convalesced and assumed a new role supporting the war on the homefront.

His job looked much like a World War II-style “war bond tour” with travel and public speaking. Local news agencies touted Murphy as the first Mississippian wounded in Iraq. He obediently smiled, waved and shook hands. No one seemed to care he wasn’t from Mississippi. Murphy adopted the role as the primary point of contact with the families of Marines still deployed. He earned their trust and admiration despite the stories he fabricated to convince families their loved ones were safe overseas.

Fast forward two years, Murphy’s morale reached an all-time low. The intervening time improved little about his situation. His arm refused to properly heal. His hand worked but felt minimal sensation even after a major surgery on his ulnar nerve. He pushed himself to get back into fighting shape, but regular running caused shin splints. Shin splints evolved into stress fractures.

When the unit activated again for deployment, the officers in charge refused to let Murphy come along. For the second time in as many years, the disgruntled staff sergeant would spend a combat deployment trapped at platoon headquarters in Gulfport, Miss. Seventy amtrackers from the battalion returned to Iraq in March 2005. Given his experience with the families, Murphy led the battalion’s Casualty Assistance Program, acting as the link between the Marines in combat and their families. His duties included the heartrending task of notifying spouses, siblings, mothers and fathers when their Marine was injured or killed. Tragically, he kept busy.

The unit deployed in support of a reserve infantry battalion: 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines. Anyone familiar with the Iraq war remembers this deployment, where 3/25 suffered staggering and historic losses. The Marines from 4th AABn ferrying the grunts around the battlefield were not immune.

On Aug. 1, Staff Sergeant Shannon Sweeney arrived at the Naval Construction Battalion Center in Gulfport. An armorer by trade, Sweeney had recently wrapped up several years as a recruiter in Montgomery, Ala. Her new orders placed her on I&I duty with Murphy, serving as the chief armorer for the Marines working on the naval base. Two days after she came on deck, Aug. 3, 2005, tragedy struck in Iraq. One of the platoon’s AAVs detonated a roadside bomb near Haditha, killing 15 of the 16 men inside. The incident remains the deadliest attack of the war. Three amtrackers died in the explosion. A fourth, the driver, survived after the explosion ejected him through his hatch, landing in the road a few dozen feet away.

Word of the disaster raced back to Gulfport. Murphy enlisted Sweeney and several others to aid in his casualty assistance duties. Murphy knew each of the amtrackers killed or wounded, one of whom he had personally recruited to join the unit. A shockwave jolted the entire community as the Marines traveled from home to home through Mississippi and Louisiana speaking to families. Numerous others reached out to Murphy as their one and only trusted link to their son or brother still in combat. No stories about Iraq could be fabricated now to make them feel better. Everyone stood on edge, dreading every phone call or knock on the door.

One week later, another potential disaster brewed beyond the horizon. A tropical storm took shape over the Atlantic, barreling past the Lesser Antilles toward the East Coast of the United States. The storm increased to a Category 2 hurricane on an uncertain path. Murphy paused the work coordinating funerals to stand up a quick reaction team in the event the storm made landfall.

“I volunteered for the react team when I got to the unit several years earlier,” Murphy remembered today. “As one of the only amtrackers on the permanent I&I staff, I just felt like I was one of the only ones who could be available on a sustained basis. SOPs existed on how the team should operate, but they were written a long time prior and there had never been an actual incident that required the deployment of Marine Corps assets. Every time we stood this team up for whatever hurricane was coming through, we took it serious initially, but then we kind of realized that we basically just went down to the ramp with the tracks and played cards for a day or two. Nothing happened, then we went home. That happened probably four or five times while I was there.”

With the unit deployed, a skeleton crew remained behind in Gulfport. Even fewer of the Marines left were licensed to drive an AAV or had even been inside of one. Assembling a technically qualified team would be impossible. Murphy tapped Sweeney to join him. The fact that she was brand new to the unit and an armorer, completely unfamiliar with AAVs, meant little. The fact that she was a female, at the time still barred from service in combat arms, including AAVs, meant even less. She was a Marine, and a competent staff noncommissioned officer. Murphy would teach her whatever she needed to know. Within a day or two, the hurricane swerved back out to sea and dissipated, avoiding the continent entirely. The reaction team stood down. Murphy and Sweeney rejoined the others in the casualty assistance office.

Work with the families continued. Sweeney stayed so busy that after more than three weeks in Gulfport, she had not found the opportunity to enter the armory she was sent to administer. None of the Marines paid much attention on Aug. 25 when another hurricane made landfall more than 600 miles away on the east coast of Florida. Barely a Category 1, computer models varied on the path it might take. The storm tore across the peninsula into the Gulf of Mexico and intensified over the warm waters. The hurricane grew into a Category 5 monster with sustained winds of up to 175 miles per hour, one of the strongest recorded hurricanes ever to enter the Gulf. Models shifted and aligned. Everything pointed to a second landfall in Louisiana. President George W. Bush declared a state of emergency along the Gulf Coast. The mayor of New Orleans ordered a mandatory evacuation of the city, stating, “We are facing a storm that most of us have long feared.” By Aug. 28, every Marine and Sailor stationed in Gulfport knew the hurricane by name: Katrina. Murphy dropped all other duties to form another reaction team.

He needed six total, three Marines apiece to fill out two amtrac crews. Sweeney joined up just as she had earlier in the month. Like Murphy, another Marine staff sergeant remained at the base healing after his leg was broken in a motorcycle accident. Like Sweeney, he had zero AAV experience, but as a communications Marine, he could work the radios. Two brand new privates first class had just graduated from their military occupational specialty schools and checked into the platoon. One was a mechanic and the other, by sheer luck, was an AAV crewman who was licensed to drive. With five down and one to go, Murphy racked his brain. The Marine detachment at the base was spread so thin that there was not a single additional leatherneck available. Finally, he called his neighbor, a U.S. Navy Seabee assigned to Gulfport. Murphy discovered the Sailor was ordered to remain behind on a working party after his family evacuated. Murphy visited the base commander and negotiated his neighbor’s release, embellishing the Sailor’s AAV experience. He had, after all, brought his kids to climb over the vehicles a time or two, which made him more experienced than most others left.

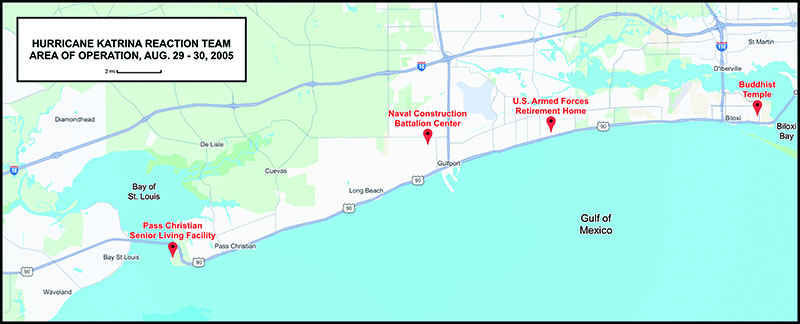

Katrina slammed into Louisiana on Aug. 29. Murphy staged the team’s two AAVs inside the structure that housed the base’s hurricane command post. He attended all the briefings. None of the Seabees seemed to understand the capability the Marines and their amphibious machines could offer. Meanwhile, the storm raged.

“I am from Ohio; the biggest thing I’d ever seen was a snowstorm,” Sweeney mused today. “The wind started picking up. We could see the commissary from where we were. The cars in the parking lot got rocked. Windows were busted out. Eventually, the roof was blown off. That’s when I knew this was for real. We were going to have to go to work.”

Murphy argued the case for deploying his team. All the Marines felt obligated to go out into the storm and help in the way that only they could. Murphy especially, having lived and worked in the area for nearly five years, felt compelled to assist his community. With power lines coming down, buildings collapsing, wind howling and water rising, the AAVs remained the only vehicle still able to negotiate the area. The base CO flatly refused. No one was leaving the command post. Hours ticked by into the evening as the eye of the hurricane passed over the Mississippi coastline. Finally, an official call for help arrived.

“I don’t remember if our cell phone coverage was dead yet, but the CO had some kind of contact with the police department in Biloxi, which was the city about 15 miles to our east,” Murphy said. “The messages we were getting from Biloxi were like, ‘hey, we’ve got people hanging out in trees over here and we can’t get to them.’ I overheard all of this and approached the CO while he was figuring out how we could respond or if we could respond at all. I told him, ‘Sir, I’ll pick my team up and we can go right now.’ Finally, he gave us permission to go. His condition, though, was that no one else was leaving the command post and literally gave us the keys to the base gate. We were on our own and we took off.”

The team exited the base headed east along Pass Road, a main thoroughfare into Biloxi. Winds up to 100 miles per hour pummeled the 30-ton machines as they crawled through an unrecognizable debris field. Rain battered Murphy’s face as he peeked through a crack in his hatch, driving into the dark. The AAVs splashed through tides fluctuating up to 8 feet across the already flooded urban landscape.

“It was the middle of the night, the winds were high, the waves were coming in,” Sweeney remembered. “It was for real like a movie. It was just crazy to go out there and see what water and wind can do to property.”

They finally reached the Biloxi police department headquarters, where officers came on board. They directed Murphy several blocks farther east into areas of the city totally inaccessible before the Marines arrived. Murphy weaved into the area. Suddenly, despite the winds and rain, the overpowering reek of natural gas smacked him in the face. He halted in the road, imagining all the sparks his tracked vehicles made while traveling on a paved surface. Through the storm ahead, he could see people, stuck and waiting for someone to save them.

“When you’re in Iraq doing a convoy or something, you get that serious pucker factor,” said Murphy. “That’s how this was. But at the same time, we could physically see people in despair so it’s not like we were ever going to stop doing whatever we were going to do. We couldn’t get over there on foot, or else we were going to wind up in the trees with everybody else. So, what do we do? All of my decisions were based on some-what-informed guesses that, thank God, happened to work out.”

Murphy ordered the police out of his AAV into the other vehicle behind him. Sweeney and Murphy’s neighbor volunteered to remain with him in the lead vehicle as he drove alone over the remains of houses toward the victims. All three buttoned up inside, praying that nothing would ignite the gas. They rescued victims one or two at a time until they arrived outside a Vietnamese Buddhist temple. The people who met him spoke no English, but Murphy quick-ly surmised that a large group had gathered inside. He filled the amtrac to capacity and returned to the other vehicle staged at the police station. Once the civilians offloaded into the care of first responders at the station, the AAV crew immediately turned around heading back into the area.

For the next several hours, Murphy drove trip after trip with Sweeney and his Seabee neighbor, evacuating the Buddhist temple. Once completed, they moved on to other areas farther east searching for anyone else stranded in the storm.

“With the wind, we were worried about getting smashed in the face by something, so we kept our comm helmets on just in case,” said Murphy. “But we were very serious about clearing everything. We came across this freaking reptile museum thing. I knew it had snakes and stuff in there. I f—king hate snakes. I hate them! But I had to go in there. I’m wading through water up to my nipples imagining the worst-case scenario. Not only do I have to go looking for people in this snake house, the damn things could be floating right up to my face! I went in there, but I was NOT happy about it. But I also knew that we had to go make sure, and I wasn’t going to force anybody else to do it.”

Throughout the night, the two Marine amtracs remained the only rescue vehicles operating in the entire area. They encountered their first body outside a casino. Mercifully, the living they encountered far outnumbered the dead. By the end of the night, Murphy’s team searched all the worst affected areas from Biloxi Bay all the way back to Gulfport, rescuing nearly 150 civilians. The two AAVs pulled back through the gate at the Seabee base well after midnight.

The team crashed for a few hours of well-deserved rest. Murphy rose with the sun to attend the next briefing from the base commander. By the morning of Aug. 30, Katrina pushed north of Gulfport, a pristine blue sky left in her wake. The trail of extraordinary ruination attested to her warpath. Through the night, more calls for assistance poured in. To the west, leaders from Pass Christian sounded the alarm over citizens trapped, the majority of whom resided in a waterfront senior living facility. Murphy’s team saddled up.

With the water greatly receded and the storm abated, the amtracs covered ground more quickly. Still, the rubble-strewn streets severely hindered progress. Future analysis of the storm would later reveal an unfortunate distinction for Pass Christian. The small town endured the worst part of Katrina’s storm surge, maxing out nearly 28 feet high. As a result, almost every structure lay in complete devastation. Cars and boats and pieces of buildings filled every street and yard. Power lines tangled the mess together, with sewage overflowing to contaminate the water. The Marines found numerous civilians in Pass Christian, not trapped, but having already returned to their homes only to find them vanished overnight. The team passed out case after case of water bottles to them all, now destitute and dehydrated.

The local chiefs of fire and police came onboard to help the amtracs navigate to the senior living facility. The complex stood in a marshy area on Henderson Point at the mouth of the Bay of St. Louis. According to the locals, the entire first floor was completely destroyed, and the facility had not been evacuated before the storm hit. Even in AAVs, the Marines couldn’t reach the site. Murphy explored multiple paths into the area, but an opening refused to yield.

“I was looking at the map and realized we were going to have to go out into the open water. That was our only way to get there,” Murphy said. “I know that’s what these AAVs are designed for, but I didn’t have time to do a pre-water op check to make sure they would actually float. And even if we found something, what’s that going to change? So, we just made sure there were hull plugs in the bottom and that the bilge pumps worked, then we took off.”

The AAVs pushed through debris-filled water around Henderson Point. The wreckage of the St. Louis Bay Bridge loomed ahead. Two days earlier, the bridge linked the 2-mile gap across the mouth of the bay. Now, huge spans of concrete angled out of the water against regularly spaced pillars like a row of fallen dominoes. The amtracs conducted an amphibious landing up the sandy beach in front of the facility and stopped outside the front door. The Marines spent the remainder of the morning evacuating residents of the home and searching the marsh around it for any other victims.

As the rescue mission in Pass Christian wound down, Murphy received a call from the command post. The CO needed a radio retransmission site established to support his communications network. He selected the roof of the U.S. government-sponsored Armed Forces Retirement Home in Gulfport as the ideal spot. The tracks rolled up to the building in the late afternoon. While the Marines set up antennas and comm equipment on the roof, Murphy checked in with the retirement home staff and residents.

Throughout his time in Gulfport, Murphy remained in close contact with the facility, visiting routinely to meet the veterans who lived there. He learned from the staff that through the night, the first floor flooded, and residents were evacuated to the higher floors. Through the chaotic process, conducted in dark-ness while the hurricane raged, two residents fell down the stairs sustaining critical injuries. After the comm gear was installed, Murphy directed his team to load the injured victims on stretchers into the tracks, along with several others suffering from heat exhaustion. The Marines evacuated the casualties to a nearby hospital. Bewildered staff watched the amphibious monsters roll right up to the awning designated for ambulance entrance to the emergency room.

“The best part of that day was when we were offloading those guys,” remembered Murphy. “One of them, an old World War II Marine looked at me and said, ‘Man, I always wanted to ride in one of those things, so thank you!’ ”

The team returned once more to the command post. By the end of day two, they rescued more than 70 additional victims, their total now well over 200 in barely more than 24 hours. Word of their staggering feat failed to impress or failed to reach beyond the city of Gulfport, however. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) arrived on scene, took control of the disaster response, and shut down all Department of Defense rescue efforts.

Murphy loaded the team up again the following day and drove the AAVs down Interstate 10 into Louisiana to where FEMA organized their command. With news reports of looters on the rise and police being shot in New Orleans, Sweeney opened her armory, finally seeing it for the first time, and issued sidearms to each member of the team before they departed. Now several days into the hurricane response, the urgent rescue efforts transitioned into a methodical recovery. FEMA wielded strict control and accounting over every search and recovery asset. They assigned the Marines to link up with an urban search- and-rescue team out of Virginia to search areas along the coast in western Mississippi, through Waveland and Bay St. Louis. The tracks got them into the area, but the searching had to be done on foot.

“We were wading through mud and filth up to our waist with sticks trying to figure out if we were stepping on bodies in the mud beneath us,” Murphy said. “It was pretty gross. We did that for hours. I remember getting down to the shore where a row of trees extended all the way to the beach. There was a line of trash across the top of every single tree where the waterline had risen. We had been out in some high water and saw it for ourselves, but seeing that was like, holy cow, I couldn’t believe it.”

“I think the hardest part for me was seeing people coming back and trying to find what would have been their property, but there was nothing there,” added Sweeney. “Stuff was everywhere; a door frame hanging from a tree, an exhumed casket washed up somewhere. People were trying to sift through all of that, and we were trying to help them get to it as best we could.”

After a few days of searching, Murphy learned that additional 4th AABn assets were finally involved in the effort. Apparently, word of their exploits and capabilities got around and FEMA called for additional AAVs. The battalion’s Company B loaded numerous tracks onto trailers at their home base in Jacksonville, Fla., and trucked into New Orleans. With more DOD personnel on scene, Murphy requested to stand down his exhausted team. They hardly showered or slept in more than 96 hours. They had yet to check on their own homes and loved ones. The battalion commander told Murphy to send his team home to take care of their families. Their job was finished.

Murphy drove home to his family in North Carolina. The visit was extremely short-lived. His job had only just begun. Before Katrina hit, he and Sweeney worked tirelessly to visit families and calm their fears, worried sick over the Marines in Iraq. Now, fortunes abruptly reversed. Messages poured into Gulfport from the Marines overseas, unable to contact their families. Halfway around the world, they saw the pictures and knew Katrina was bad. They feared the worst for their loved ones scattered across the impacted area. Murphy and Sweeney took on the task of visiting them all once again.

“The second we stood down, our focus shifted to driving to every single one of those 70 reservists’ families,” said Murphy. “We had to let the boys know their families were OK. That took a long time. We took chainsaws with us and things like that and did whatever we could to reach them. Thank God, no big issues with any families. We felt it was super important to get that information back to them after the losses they suffered at the beginning of the month.”

The Gulf Coast’s recovery after Katrina would take many years to return to a version of normalcy. Through the remainder of 2005, the region remained in a state of shock and desolation. Nothing about life endured unaffected, but life continued on. That fall, officers over the region named Sweeney as the lead coordinator of the Toys for Tots campaign based out of Gulfport. Always a tremendous undertaking, even under normal circumstances, how could toys be collected and distributed through such a ravaged area?

“The short story is that we just did it,” Sweeney reflected. “I’ll tell you one thing, as screwed up as this United States can be, we can really come together.”

Tractor trailers full of toys offloaded in Gulfport every day from across the nation. If they ran short, Sweeney drove an hour north to the Toys R Us in Hattiesburg to boost their stock. The Marines returned from Iraq in October and became Sweeney’s elves in the operation. Numerous nonprofit organizations set up stations from Pass Christian to Biloxi, passing out toys and provisions.

“The Toys for Tots Foundation gave me $50,000 to host a Christmas party,” Sweeney said. “I had no idea how or where they wanted me to pull that off. Our unit had some ‘good ol’ boy’ networks, and we found an indoor skate rink in Biloxi that didn’t really get damaged, so I threw a party in there. Schools were back in session, meeting in trailers. I printed off a ton of tickets at the office and handed them out to all the trailers. We brought in a ton of toys and a Marine dressed as Santa. Everyone got Subway, a Coke and toys. Throughout the whole campaign, we handed out over 90,000 toys and books. We didn’t turn anyone away and everyone was grateful.”

In December 2005, each member of the reaction team received the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal. The Corps also announced that all Marines involved in disaster relief efforts after Katrina would rate the Humanitarian Service Medal and the Armed Forces Service Medal. Sweeney was honored with a more prestigious recognition the following summer. For the combination of her rescue efforts with the reaction team and her critical role in the successful Toys for Tots campaign benefiting the devastated area, Sweeney received the Gerald R. Ford Medal for Distinguished Public Service. She accepted the award presented by the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Founda-tion in Washington, D.C., alongside four other recipients, one medal presented to a nominee from each branch of service. Sweeney retired in 2019 after 30 years of service. She achieved the rank of master gunnery sergeant, the first female in her MOS to earn this highest rank.

Murphy was selected for warrant officer in late 2005. He moved to Quantico, Va., to attend The Basic School in February 2006. While there, he too learned that others had nominated him for a higher personal decoration. In a ceremony in front of his classmates, an officer pre-sented Murphy with the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, the highest noncombat decoration awarded for heroism that a Marine or Sailor can receive. He later learned that no one within his 4th AABn chain of command outside of Gulfport even knew his team was operating until after the second day. The officer who penned his award citation confided that he was instructed to either write up Murphy’s initiative for a medal or write up his freelancing for an Article 32 investigation. Murphy eventually retired from the Marine Corps in 2020 as a chief warrant officer 4.

Today, 20 years later, the actions of Murphy’s team in the aftermath of Hur-ricane Katrina remain a preeminent, and perhaps unparalleled example of Marines on the homefront being exactly who the American public expects us to be. The 33rd Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Michael Hagee, personally called attention to the Marines who responded to natural disasters in 2005 in his Marine Corps birthday message that November.

“This past year has been one of con-tinuous combat operations overseas and distinguished service here at home … In Iraq and Afghanistan, Marine courage and mastery of complex and chaotic environments have truly made a difference in the lives of millions. Marine compas-sion and flexibility provided humanitarian assistance to thousands in the wake of the Southeast Asian tsunami, and here at home, Marines with AAVs, helicopters, and sometimes with their bare hands saved hundreds of our own fellow Americans in the wake of Hur-ricanes Katrina and Rita. Across the full spectrum of operations, you have show-cased that Marines create stability in an unstable world and have reinforced our Corps’ reputation for setting the standard of excellence.”

“There was no game plan for what we did at all,” Sweeney reflected. “We just had to go out as a team and do what we had to do to help the folks of Mississippi along that 26-mile stretch of Gulf Coast. Witnessing something like that, you start to view things differently. You cherish things more. You care for what you have. Over the years, the higher in rank I got, I always tried to make sure that my Marines and their families were taken care of. We are all part of the puzzle and have to be ready.”

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-13. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.

Featured Image (Top): Marine AAVs conduct an amphibious landing in Pass Christian, Miss., to rescue civilians stranded at a senior living facility on the shore at the mouth of Bay of St. Louis. The building proved completely inaccessible by land, even for AAVs, requiring the Marines to utilize the vehicle’s unique amphibious capability. (Photo courtesy of Shannon Sweeney)