Operation PROVIDE COMFORT

By: Col James L. JonesPosted on August 15,2025

Article Date 01/09/2025

Humanitarian and Security Assistance in Northern Iraq

>Originally published in the Marine Corps Gazette, November 1991.

The multinational relief effort to aid Kurdish refugees in southern Turkey and northern Iraq was a “joint” operation in every sense of the word. Here the commanding officer of the principal Marine unit involved, the 24th MEU(SOC), details the events that triggered this humanitarian mission.

Hoping to take advantage of the allies victory over Iraq in DESERT STORM, dissident factions within Iraq seized on the moment to launch a courageous, but unsuccessful attempt to topple Saddam Hussein from power this past March. In the aftermath of his army’s defeat, Saddam Hussein unleashed the still-capable remnants of his battered force against the Kurdish population of northern Iraq, triggering a desperate human exodus towards sanctuaries in the bordering nations of Turkey, Iran, and to a lesser extent, Syria.

As the media of the world focused on the developing human tragedy of the Kurdish people fleeing by the hundreds of thousands before a vengeful Iraqi Army, worldwide outrage galvanized allied coalition support. From the moment the decision was made to air drop supplies to the fleeing refugees on 7 April, it was clear that there was yet another chapter to be written about DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM. It would become known as PROVIDE COMFORT.

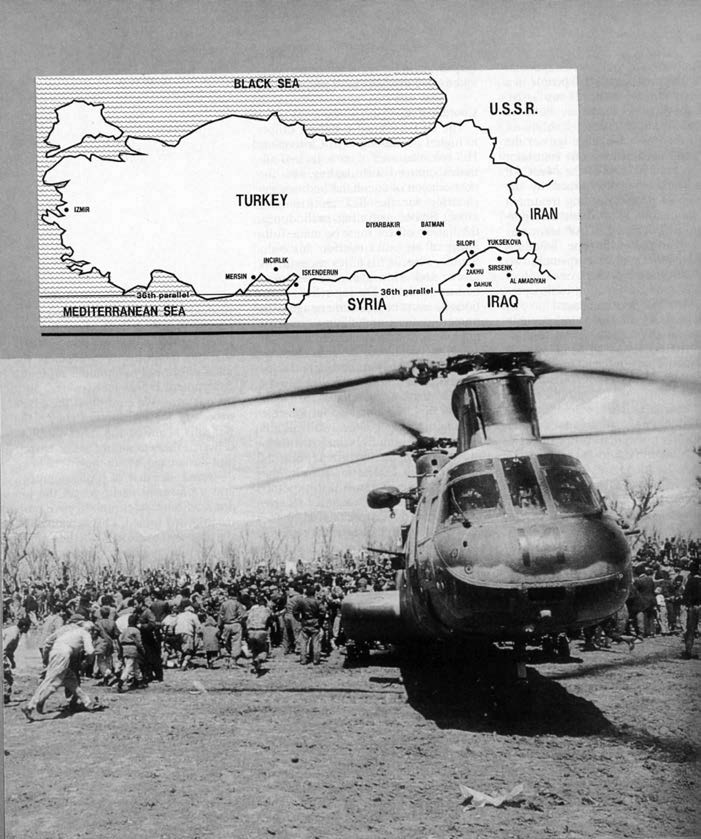

As the situation unfolded during March and early April, the Kurds’ flight ended in the mountains of southern Turkey, where an estimated 500,000 refugees were massed, having been pushed over the border and herded into so-called “sanctuaries” by Turkish forces. To the east and south, an estimated 1.3 million Kurdish refugees huddled in similar camps along the Iranian border. The fate of this group has yet to be determined.

It was during the last few days of March that BGen Richard Potter, USA, was ordered to insert his 10th Special Forces Group into the refugee camps. At this time there were 12 such camps with an average population of approximately 45,000. Conservative estimates had approximately 600 people dying of exposure, malnutrition, and disease daily. In this area of the world, March is still a winter month and many camps abutted snow-capped peaks. The many trails from Iraq were littered with abandoned possessions that no longer served any utility—broken-down cars, appliances, family heirlooms, furniture, suitcases that had become too heavy to carry, and tragically, people who were unable to withstand the rigors of the march and simply stopped walking, waiting for the cold to end their suffering.

Within days of its insertion, the 10th Special Forces Group organized and identified camps and drop zones, provided medical assistance as needed, and made plans for security requirements. The 10th Special Forces Group formed the first element of what became Joint Task Force Alpha (JTF-A), whose principal mission was resupply of the Kurdish refugees. JTF-A was based in Incirlik, Turkey, along with the headquarters for Combined Task Force (CTF) PROVIDE COMFORT, initially commanded by MGen James Jamerson, USAF, and subsequently by LtGen John M. Shalikashvili, USA.

On 9 April, the 24th Special Operations Capable Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU(SOC)) was into its third month of a planned six-month Mediterranean deployment when the call went out to respond to the rapidly developing situation in northern Iraq. Embarked aboard the USS Guadalcanal (LPH 7), USS Austin (LPD 4), and USS Charleston (LKA 113), the 24th MEU(SOC) was in the midst of a landing operation in Sardinia, Italy, when the commander, U.S. Sixth Fleet, ordered the amphibious ready group to begin backload, depart the waters of the western Mediterranean, and proceed to the port of Iskenderun, Turkey, for duty with CTF PROVIDE COMFORT. The backload was completed the next morning and the three ships arrived on station on 13 April. The following morning, the 24th MEU(SOC) and Amphibious Squadron 8 (PhibRon-8), commanded by Capt Dean Turner, USN, reported to MGen Jamerson and his deputy, BGen Anthony C. Zinni.

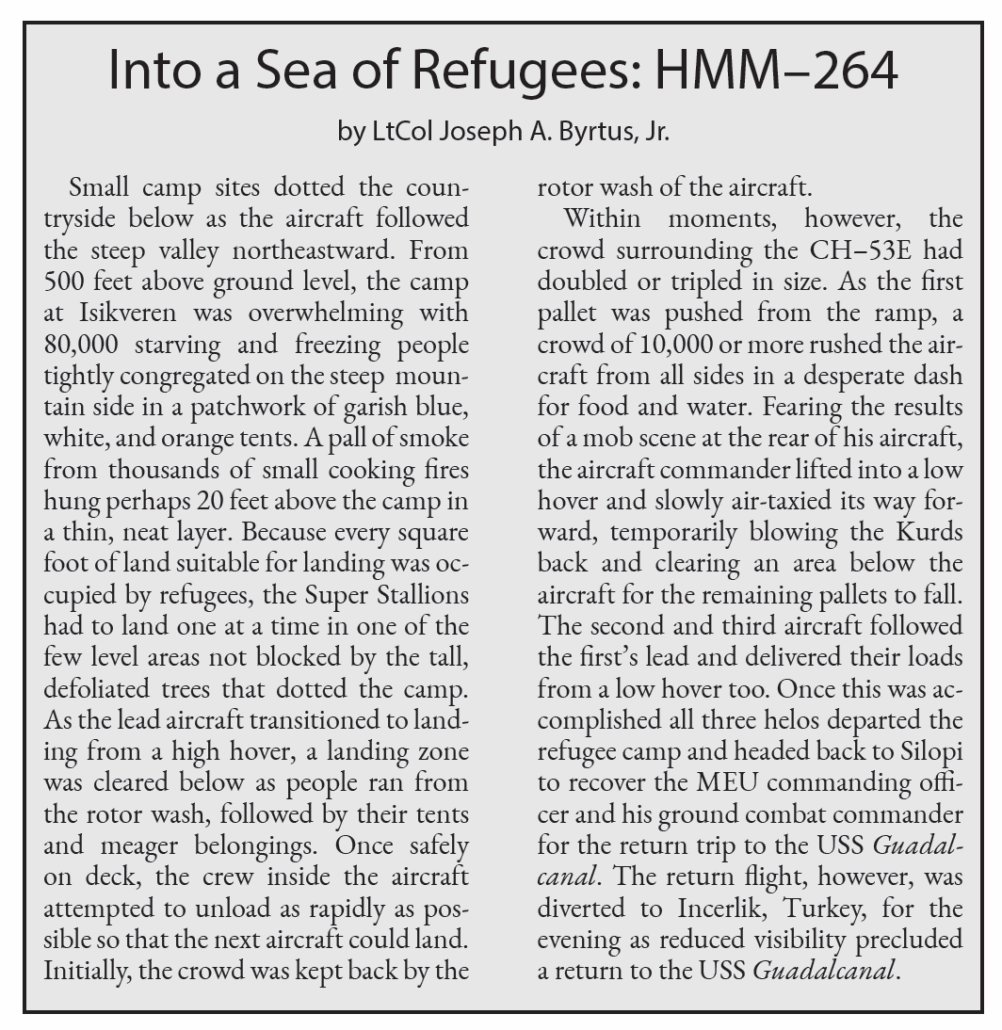

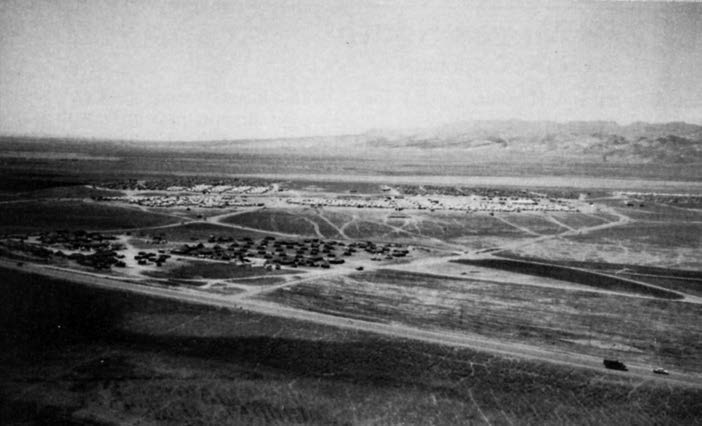

The mission was clear. The 24th MEU(SOC) was to establish a forward support base at Silopi, Turkey, from which helicopters could begin to carry supplies to refugee camps in the mountains. Implied in the mission was the establishment of a forward arming and refueling point (FARP) and a Marine air control detachment to run the airfield. By 15 April, HMM-264, the aviation combat element of the 24th MEU(SOC), had displaced itself 450 miles inland, set up its base, and had begun its humanitarian mission with 23 helicopters in support of BGen Potter and JTF-A (see “Into a Sea of Refugees”). During the following two weeks the Squadron would deliver over 1 million pounds of relief supplies and fly in excess of 1,000 hours without mishap.

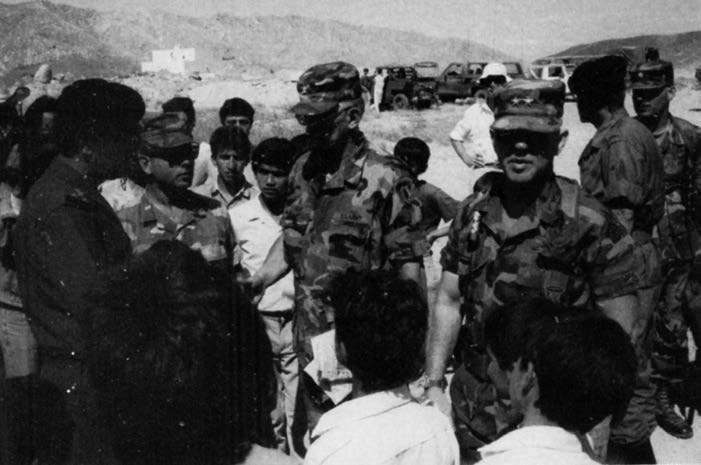

Rapidly changing events revealed that the entire 24th MEU(SOC) would be required ashore in short time. Within a few days, the unit was operating out of Silopi, Turkey, preparing to be part of the security force that was to enter northern Iraq. On 19 April, Marines provided the security element for a meeting between LtGen Shalikashvili and an Iraqi delegation at the Habur Bridge border crossing in Iraq. At that meeting, Iraqi representatives were informed that coalition forces intended to enter Iraq on 20 April; the mission was to be humanitarian; there was no intent to engage Iraqi forces; Iraqi forces were to offer no resistance; and a Military Coordination Committee would be formed for the purpose of maintaining direct communication with both Kurdish and Iraqi authorities.

While plans to cross the border to the west of the city of Zakhu were being finalized on 19 April, allied coalition forces received instructions from their respective governments to proceed towards the Turkish-Iraqi border. CTF PROVIDE COMFORT responded to the orders of the Supreme Allied Commander Europe, Gen John R. Galvin, USA, the unified commander in Germany who had cognizance over all operations in the area, to proceed into northern Iraq and establish security zones to expedite the safe transfer of refugees from their mountain havens to the countryside they had originated from. LtGen Shalikashvili quickly activated Joint Task Force-Bravo (JTF-B), which would be responsible for this part of the mission. Its focus would be to neutralize the Iraqi Army in the northern region of Iraq and implement a plan to reintroduce 500,000 Kurdish refugees back into that country.

The problem for JTF-B was in creating conditions in Iraq that would entice the refugees to return voluntarily to the region. Climatic conditions are such that there are only two seasons in the region—winter and summer. Coalition forces were already witnessing winter’s last gasp. Soon the mountain streams, which were the main source of water for many of the refugees, would dry up under the intense heat of summer. For obvious reasons, it was critical that the refugees be out of the hills before this occured.

On 17 April, MajGen Jay M. Garner, USA, arrived in Silopi from his post as deputy commanding general, V Corps, in Germany, with the lead element of what was to become the JTF-B staff. At the outset his troop list consisted of the 24th MEU(SOC), which was given the task of conducting a heliborne assault into a valley to the east of Zakhu on the morning of 20 April. Overhead U.S. Air Force A–10s, F–15s, and F–16s provided air cover, while the Iraqi Army watched precariously from the high ground surrounding Zakhu. Previously inserted force reconnaissance Marines and Navy SEALs had established observation posts along the main avenues of approach and key terrain around the city. Assault helicopters were deployed carrying Marines from Battalion Landing Team 2/8 (BLT 2/8), commanded by LtCol Tony L. Corwin, to designated zones near the city. Reports from the recon units confirmed the presence of a significant number of Iraqi reinforcements billeted near the MEU command element. Consequently, LtCoI Corwin sent emissaries to the Iraqi positions with clear instructions concerning the movements he expected the Iraqi Army to make in withdrawing from the region and the city of Zakhu. As a demonstration of humanitarian intent, Marines erected 12 refugee tents before nightfall on 20 April in what was to ultimately become one of the largest resettlement camps ever built. Patience and firmness paid off within a few days as the Iraqi Army issued orders to withdraw. By nightfall on 23 April, Marines occupied the key positions and road network around the city.

MajGen Garner and his JTF-B staff were headquartered along with the command element of the 24th MEU(SOC) in the deserted headquarters of the Iraqi 44th Infantry Division. Garner immediately directed the bridge and road leading from the border to Zakhu to be opened for traffic. This was particularly significant as the Habur Bridge at the border would become the only means by which surface convoys could pass from Turkey into Iraq.

On 22 April, LtCol Jonathan Thompson, commanding officer, 45th Commando, Royal Marines (United Kingdom), and LtCol Cees Van Egmond, 1st Air Combat Group, Royal Netherlands Marines, reported for duty to MajGen Garner, who placed both units under the tactical control of the 24th MEU(SOC). With a total force of 3,400 Marines from three nations, MajGen Garner lost no time in developing a plan to rid Zakhu of Iraqi oppression

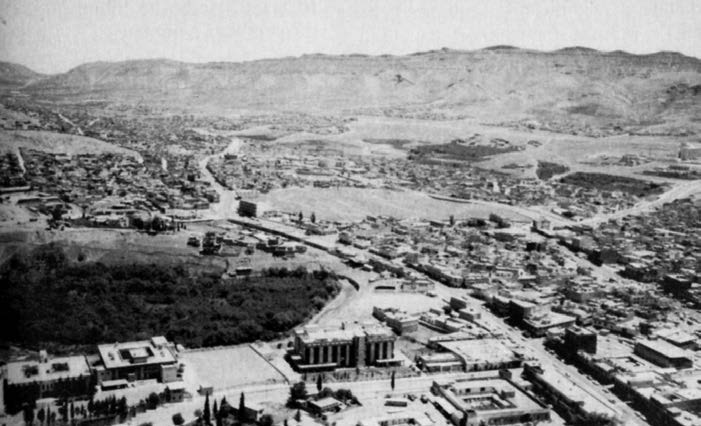

Zakhu, a city of 150,000 under normal times, was a ghost town when coalition forces arrived there on 20 April. Fewer than 2,000 inhabitants remained. Those missing were still in the mountain camps of southern Turkey. Their homes had been looted and vandalized by the Iraqi Army, which continued pillaging local towns and villages as it retreated south.

Despite agreeing to withdraw his army, Saddam was not about to surrender Zakhu without a last effort to retain control of the city. He did so by ordering 300 “policemen” into Zakhu to maintain law and order and protect coalition forces from Kurdish rebels. Clearly, the few residents left in Zakhu were still being terrorized. Something had to be done.

Col Richard Naab, USA, the recently assigned head of the Military Coordination Committee, met daily with BGen Danoun Nashwan of the Iraqi Army to explain coalition intent and expectations. After several meetings, a demarche was drafted and released on 24 April. Its key points are listed below:

• Iraqi armed forces will continue to withdraw to a point 30 kilometers in all directions from Zakhu (in other words, out of artillery range).

• Iraqi police will be immediately withdrawn from Zakhu.

• Iraq will be allowed no more than 50 uniformed policemen in Zakhu at any one time. They would have to be indigenous to the region, carry only one pistol, and display coalition force identification badges at all times.

• In 26 April coalition forces will enter Zakhu for the purpose of verifying compliance and would begin to regularly patrol the city.

• Coalition forces will establish a security zone complete with checkpoints within a 30-kilometer radius around Zakhu. No weapons other than those of coalition forces will be permitted in the zone.

• No members of the Iraqi Army will be permitted in the security zone—in or out of uniform—without approval from the Military Coordination Committee.

Shortly after the issuing of this de-marche, the Iraqi police were observed boarding buses headed south. While the full impact of the demarche was being studied by the Iraqis, LtGen Shalikashvili and MajGen Garner lost no time in directing the 24th MEU(SOC) to establish this security zone, which it was thought would permit the Kurds to consider coming out of the mountains without fear.

During the hours of darkness on 25 April, BLT 2/8 cordoned off the city from the south, east, and north, while Dutch Marines sealed off the western approaches and ensured the integrity of the bridges at the border. British Royal Marines from 45th Commando, having just arrived from Northern Ireland, were tasked with patrolling the streets of Zakhu, sending what few Iraqis remained scurrying for an escape route. By nightfall on 26 April, Zakhu enjoyed its first taste of freedom.

During this time, the resupply effort continued. On 26 April alone, HMM-264 delivered 24.5 tons of relief supplies to the refugees. They were soon augmented by helicopter assets from other coalition forces that had begun to arrive in the area, making operational the Combined Service Command (CSC) at Silopi, Turkey. Other reinforcements were forthcoming as well. On the morning of 27 April, the 3d Battalion, 325th (3/325) Airborne Combat Team, commanded by LtCoI John Abizaid, was placed under the tactical control of the 24th MEU. The 18th Engineer Brigade, commanded by Col Steven Windsor, USA, reinforced by Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 133 (SeaBees), also arrived during this same timeframe, providing much needed relief for the Sailors and Marines of the 24th MEU(SOC) who, alone, had raised 1,100 tents in 10 days.

Another capability of critical impor-tance throughout PROVIDE COMFORT was the presence of the U.S. State De-partment Disaster Assistance Relief Team headed by Fred Cuny, a former Marine. This team was critical in help-ing coordinate the actions of the many multinational government and nongov-ernmental organizations that played a role in the operation. Bolstered by years of expertise in such matters, Cuny was invaluable in prosecuting a humanitarian campaign that ultimately relocated 500,000 Kurds in 60 days.

24th MEU(SOC)’s MEU Service Support Group (MSSG-24), commanded by LtCoI Richard T. Kohl, also showed its mettle early on by installing a reverse osmosis water purification unit and establishing medical/dental civic action projects in Zakhu. Almost overnight, the local hospital sprang to operating capability. Coalition engineers sought to restore electricity and water to a city that had been without for months. Stores slowly reopened and people once again took to the streets, (see “Pushing Logistics to the Limit”). These initiatives were key in convincing the citizens of Zakhu that this was an army, perhaps the first in memory, that only meant them goodwill.

It didn’t take long for the message to reach the mountains. Local community leaders and Pesh Merge chiefs began arriving in Zakhu to verify for themselves the changes underway and to give proper guidance to their people in the mountains. The allies referred to Zakhu and its growing refugee camp to the east as the coalition security zone. As the demarche noted, it was to be free of visible weapons, rules which were meant to apply to Kurds as well as the Iraqi Army.

At first, only a trickle of refugees dared to leave the camps to begin the trip back to Zakhu. Soon, however, as news of a secure city inside Iraq spread to the mountains, many residents slowly began to return to their former homes. A large number of refugees, however, still refused to budge from their hilltop havens. They were waiting to see what coalition forces would do next.

As Zakhu was being repopulated, coalition leaders decided that the next move should be to the east. Already, British and French forces had probed in that direction and plans to extend the zone eastward were put into effect. First, 45th Commando pushed to the town of Batufa, a small but strategically important city, then onto the airfield at Sirsenk, another important objective, and finally to the city of Al Amadiyah, a veritable fortress dating back some 3,000 years; this became the eastern limit of what was referred to as the British sector under the 3d Commando Brigade, commanded by BGen A.M. Keeling, OBE. Again, the instruction to the Iraqis via the Military Coordination Committee was clear and unequivocal—back off and let us do our job. Compliance occurred shortly thereafter.

One area that received special consideration was Saddam Hussein’s palace complex, which was a series of partially completed mansions intended for use by Iraq’s elite. These modern structures, erected on choice properties, were guarded by elements of the Iraqi army. Iraqi negotiators did not want coalition forces to take possession of these properties and an agreement was reached that allowed Iraq to retain control of the palaces, maintain a small numerically controlled security force on the grounds, and that coalition forces would not enter the properties.

Of far greater value to coalition forces, however, was the airfield at Sirsenk. The airfield was a DESERT STORM-damaged runway, which, when repaired, could accommodate C–130 aircraft. The airfield was being looked at as the key supply point for JTF-B in northern Iraq. Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen worked feverishly for six days to repair the damaged runway. By 14 May, the airfield was operational, and a key logistical forward base in Iraq had been established.

Another key element in PROVIDE COMFORT’S logistical network involved Marines and Sailors from the 3d Force Service Support Group (FSSG), which was based with III Marine Expeditionary Force on Okinawa. Early in the operation it became apparent that additional skills resident in the landing support battalion of an FSSG would be needed. Consequently, a request was sent from CTF headquarters asking for two companies to meet combat service support requirements. As the flow of relief supplies grew, the need for this unit became greater. In response, Contingency Marine Air-Ground Task Force 1–91 (CMAGTF 1–91), under the command of LtCol Robert L. Bailey, was formed and flown in theater from Okinawa, setting up initially at Silopi. CMAGTF 1–91 organized CSS detachments that were spread out over the entire CTF operating area. Throughout the operation, CMAGTF 1–91’s element remained headquartered in Silopi, providing combat service support detachments to various nodes in the relief supply network that had been established.

The expansion of our security zone, however, was still incomplete. Coalition forces continued to press eastward, beyond Al Amadiyah. French forces, under the command of BGen Xavier Prevost, pushed out to the town of Suri, which was to become the easternmost point of advance for the allies. The famous 8th Regiment Parachutiste d’Infanterie de Marine, reinforced with medical and humanitarian capabilities (not to mention a field bakery capable of producing 20,000 loafs of bread per day), formed the centerpiece of the French sector.

By this time, the skies of northern Iraq were becoming crowded. French Pumas, British Sea Kings and Gazelles, Dutch Alouettes, Italian and Spanish Hueys, Spanish CH–47s, and American transport, cargo, and attack helicopters of every type and variety contributed heavily to the humanitarian and security missions. The 4th Brigade of the 3d Infantry Division, commanded by Col Butch Whitehead, USA, reported for duty on 26 April. This maneuver element gave Gen Garner the “eyes” he needed—day and night—to see exactly what the Iraqi Army was up to in the south. To this day, these units still patrol the skies of the coalition zone, reminding both Kurds and Iraqis that there will be no repeat of last winter’s human tragedy.

By 10 May 1991, the coalition security zone, from east to west, was 160 kilometers in length and was secured by the physical presence of allied forces. This was an important point for the Kurds who maintained that they would only return to those areas that were physically occupied by coalition forces. As dramatic as it was, the expansion of the zone to the east did not have the desired effect of launching a human exodus from the camps back into Iraq. By now, however, the reason was becoming clear. The majority of refugees in Turkey came from the city of Dahuk, the provincial capital located 40 kilometers south of the allies security zone. Kurds were willing to use resettlement camps as temporary way stations en route to their former homes, but they were unwilling to accept these camps as a permanent solution. Thus, moving toward this city became the key to resolving the refugee problem in southern Turkey where approximately 350,000 refugees still remained.

In early May, overflights of Dahuk revealed that the city was abandoned except for elements of the Iraqi Army. During normal times, Dahuk is a bustling city of 350,000, modern by contrast to most other villages or cities in the security zone. Two major roads intersect just west of the city, one going to Zakhu, the other toward Al Amadiyah. Built for the efficient movement of Iraq’s army, these roadways were also the economic lifeline of the region.

The remaining refugees in the mountains were getting restless, waiting and watching for any sign that coalition forces would move south. On the 12th of May, perhaps celebrating their new found freedom, 1,500 Kurds demonstrated in Zakhu calling for allies to move toward the city of Dahuk.

Soon after, JTF-B ordered the 24th MEU(SOC), reinforced by the 3d Battalion, 325th Regiment, Airborne Combat Team, to move south and establish checkpoints to the west and east of the city at the edge of the allied security zone (see “BLT 2/8 Moves South”). Ongoing negotiations between the Iraqis and the Military Coordination Committee resulted in an agreement that would allow humanitarian and logistical forces to enter the city along with United Nations (U.N.) forces and nongovernment organizations. Combat forces were to advance no further beyond their present positions. In return, Iraq agreed to withdraw all armed forces and secret police from Dahuk and take up new positions 15 kilometers to the south of the city. On 20 May, a small convoy of coalition vehicles entered Dahuk and established a forward command post in an empty hotel in the heart of the city. The security zone now extended 160 kilometers east to west and 60 kilometers north to south below the Turkish-Iraqi border.

Although there was considerable doubt as to whether this would be enough to attract refugees from the camps, the presence of an airborne combat team to the east of Dahuk and BLT 2/8 to the west, the patrols of the 18th Military Police Brigade throughout JTF-B’s main supply routes, the increasing capabilities of Italian and Spanish forces around Zakhu, and the presence of British, Dutch, and French forces nearby, all seemed to convince Kurdish leaders that the time was right to repopulate the security zone. Thousands of Kurds began leaving their temporary shelters heading for Dahuk.

All available transportation was used during this movement. Many refugees walked, but once on the roads and footpaths, they helped one another using cars, mule-driven carts, buses, tractors, motorcycles—whatever could be found. Coalition forces sent teams of mechanics and fuel trucks into the mountains to provide assistance to those attempting to return home. Intermediary way stations were set up by civil affairs units under the command of Col John Easton, USMCR, JTF-B’s chief of staff, to provide food, water, and medical assistance at various points along the journey.

By 25 May, the movement of refugees reached its peak. 55,200 refugees sought temporary refuge in what had become three camps in the valley east of Zakhu. The activity was feverish, but incredibly well controlled. People who had never dreamed of an operation of this magnitude were thrust together to make critical decisions. They overcame language, cultural, and ethnic barriers. Nongovernmental workers from all parts of the world joined with military forces to make this effort successful. Even U.N. representatives joined in the race against time to get the Kurdish people out of the mountains. By 2 June, the U.N. had taken over the administration of both refugee camps from coalition forces, which by this time numbered over 13,000 personnel.

At the 90-day mark, it was clear that coalition objectives were achieved. Kurdish refugees were out of the mountains and either back in their villages of origin, on their way there, or in camps built by coalition forces. In the Mediterranean, the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71), which had flown air cover over northern Iraq for much of PROVIDE COMFORT, was relieved on station by the USS Forrestal (CV 59). At Silopi, Turkey, the Combined Support Command, under the direction of BGen Hal Burch, USA, was now functioning as the logistical pivot for all supplies flowing into Iraq.

On 8 June, JTF-A was deactivated and BGen Potter’s troops began their retrograde out of Turkey. On 12 June, the Civil Affairs Command was also deactivated.

The remaining days of coalition presence in northern Iraq were devoted to continuing to stabilize the region and reassuring Kurdish leaders that although coalition forces would soon be leaving, this act would not signify a change in the resolve of the allied forces to support the Kurdish people. It was also a period of planning for the allies, who were now tasked with retrograding their forces and material from northern Iraq. At this time the unannounced date for coalition forces to be out of Iraq was 15 July. A second demarche was drawn up and presented to the Iraqi government outlining the type of conduct coalition forces expected of Iraq in the future. In essence, its terms were as follows:

• Iraqi fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft were not to fly north of the 36th parallel, which is approximately 60 kilometers south of Dahuk.

• The Iraqi Army and secret police were not to enter the security zone.

• Coalition ground combat force, composed of forces representing several nations, would be maintained across the border in Silopi, Turkey.

• Coalition aircraft, both fixed- and rotary-wing, would continue to patrol the skies above the security zone.

• The Military Coordination Committee would continue to monitor the security zone and Iraqi compliance of the terms of the demarche.

In the ensuing days, coalition forces continued their drawdown. On the morning of 15 July, Marines from BLT 2/8 along with paratroopers from 3/325 Airborne Combat Team were the last combat elements to withdraw from northern Iraq. In the early afternoon, the American flag was lowered for the last time at JFT-B headquarters at Zakhu. Minutes later, U.S. military leaders, who had entered Iraq on 20 April, walked across the bridge over the Habur River, leaving Iraq for the last time. Two Air Force F-16s followed by two A-10s made low passes over the bridge as the group made its way across the bridge. On 19 July, the 24th MEU(SOC), now back aboard amphibious shipping watched as the city of Iskenderun and the Turkish horizon slipped into the sea. After a six-month deployment, it too was finally on its way home.

>The author wishes to thank SSgt Lee J. Tibbets for his assistance in preparing this article.