“Key Maritime Terrain—Any landward portion of the littoral that affords a force controlling it the ability to significantly influence events seaward.”-Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, Second Edition 2023

Alaska is the most central place in the world … in the future, he who holds Alaska will rule the world.”–BGen Billy Mitchell, U.S. Army Air Corps, Congressional Testimony, 1935

The Aleutian Campaign may be one of the most forgotten U.S. undertakings of World War II. Its human carnage and materiel costs were not insignificant for both American and Japanese forces, yet few today know anything about it. Even among military history enthusiasts, names like Attu and Kiska often go unrecognized. Such obscurity is hardly surprising when one considers the large number of campaigns that took place across Admiral Chester Nimitz’s vast Pacific Ocean Areas during the war. Not only was the North Pacific Area a decidedly peripheral operational theater to Nimitz, but the campaign’s surprising and anticlimactic conclusion was also not one U.S. and Canadian commanders wanted to be remembered for. The subsequent decision by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) not to use the Aleutians as stepping stones to invade the Kuriles and attack the Japanese home islands from the north further contributed to its historical ambiguity.

As a case study, however, the Aleutian Campaign offers numerous insights for commanders and planners on the tensions that frequently arise between theater priorities and strategic imperatives driven by time-sensitive political expectations. It also provides lessons on why the value of key maritime terrain should be periodically reassessed from both friendly and enemy perspectives. Considering the tremendous operational and logistical accomplishments of both Japan and the United States, the inclusion of this campaign in professional military education and on reading lists could elevate discussions on distributed maritime operations as envisioned today by the Navy-Marine Corps team. Certainly, the strategic implications of seizing, occupying, and/or controlling key maritime terrain in the context of amphibious operations and expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) deserve study.

In the case of the Aleutians, the law of unintended consequences affected both sides. By seizing and retaining key maritime terrain for purposes subject to broad speculation by the United States, Japan set in motion events that reverberated well beyond the region and achieved outsized strategic effects on the pace and direction of the wider U.S. war effort. From this perspective, observations and decisions from the North Pacific Theater may have relevance to future naval campaigns against a peer adversary.

Strategic Context

The persistent presence of a relatively small but capable Japanese amphibious force in the Aleutians starting in June 1942 was an audacious affront to the nation’s sovereignty and a psychological burden on Washington. With the United States now in a global world war tilting precipitously in the Axis’ favor, the intense political pressure on the Joint Chiefs of Staff to push the Japanese out of the Western Aleutians was counterbalanced by regional fears bordering on paranoia about a Japanese invasion of the North American continent. Service commanders in theater began uncoordinated actions against the Imperial Japanese Navy and its advanced bases before they were fully ready. As the perceived Japanese threat in the North Pacific grew, a cumbersome and disjointed command and control structure was hastily concocted to oversee the massive buildup of land, sea, and air capabilities unsupported by prewar planning. Hundreds of thousands of American soldiers, sailors, and airmen, along with millions of tons of equipment and supplies, were diverted to the Alaskan theater on short notice. This military might would aggregate steadily into overwhelming land, sea, and air power until it could be focused on the annihilation of two isolated Japanese garrisons doing little more than occupying the most remote American territory in the world.

The Aleutian Allure

Comprising over 660,000 square miles of mostly wilderness and 34,000 miles of coastline, Alaska stands out prominently on the globe because of its enormous size and strategic placement in the North Pacific adjacent to the Eurasia land mass. The Alaskan Peninsula extends to the southwest from the mainland over a thousand miles before transitioning to the Aleutian Archipelago which continues in a gentle westward arc for another thousand miles. Comprised of 14 large islands, 55 smaller islands, and innumerable islets, the Aleutians appear on a map to form a natural approach route to either the North American or Asia continents. Their appeal as an invasion route in either direction quickly fades under analysis, however. The remoteness, inhospitable topography, and relentlessly harsh weather make the Aleutians unforgiving to all forms of movement and sustainment. Most of the islands are dominated by snow-covered peaks rising to 9,000 feet above the frigid, turbulent waters of the North Pacific. What level ground can be found is usually covered by muskeg—a thick, wet, spongy bog into which vehicles quickly sink up to their axles. Harbors and airfields essential for intratheater movement or to support landward operations are scarce and underdeveloped. When the islands are not shrouded in thick clouds and mist, they are battered by shrieking winds, driving snow, and freezing rain. Not even trees grow in the Aleutians. Despite these daunting conditions, neither the United States nor Japan discounted the possibility that the other side might make strategic use of the Aleutians in a war.

Preparing Alaska for War

Although the Aleutians’ strategic linkage to control of the North Pacific was generally understood, little was done to protect the archipelago until war loomed. In 1938, Congress appropriated nineteen$19 million dollars for the construction of air, submarine, and destroyer bases in Alaska but few military forces were assigned until after the war began in Europe.1 The only military presence in the Aleutians themselves was a Navy radio station and a small Coast Guard base at Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island.2 In early 1940, the War Department developed plans to increase the Army garrison in Alaska, establish a major Army base near Anchorage, develop a network of airfields across Alaska, and provide troops to protect the naval installations at Dutch Harbor, Sitka, and Kodiak.3 The 750-soldier-strong Alaska Defense Force was created in July 1940 under the command of the energetic and flamboyant Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner of, the US Army. The remoteness of the proposed base locations, poor weather, and the lack of existing transportation infrastructure delayed progress on these plans until mid-1941—though Buckner spared no effort in tackling the myriad of tasks before him.4

Buckner was emphatic that Japan not be allowed to gain an expeditionary lodgment anywhere in Alaska from which they could launch air and naval operations across the North Pacific.5 He focused on defensive preparations, but remained convinced of Alaska’s offensive potential, believing the Aleutian Chain formed a “spear pointing straight at the heart of Japan.”6 He traveled throughout the archipelago identifying every island where an airfield could be built: Umnak, Adak, Amchitka, Kiska, Shemya, and Attu. Before the war’s end, all would host advanced air bases with semi-autonomous garrisons to support maritime reconnaissance and offensive air operations.7

Japan’s North Pacific Gambit

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Imperial High Command commenced a war of conquest to establish its long-desired Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. By late April 1942, Japan had swept aside Allied power and seized strategic terrain across the Pacific at the cost of nothing larger than a destroyer.88 The elated Japanese High Command chose to capitalize on this momentum and press on to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands to set conditions for an invasion of Australia.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, respected American industrial capacity enough to know that time was not on Japan’s side. He believed their only hope for victory lay in keeping America on the defensive while striking a decisive blow against what remained of the U.S. Pacific Fleet—principally its aircraft carriers—while Japan still had the advantage.9 Such a victory might compel Washington to recognize Japan’s expanded empire and negotiate an end to the war. To this end, he sought to draw the American fleet from Hawaii into the Central Pacific where it could be destroyed by Japanese air power. To lure in the American carriers, Yamamoto developed an ambitious plan to seize Midway and conduct diversionary attacks in the western Aleutians. From Midway, he could project enough land-based air power to form a protective barrier for Japan straddling the North and Central Pacific.

Japan’s Aleutian operation was intended to capture or destroy “points of strategic interest” in the Aleutians and check further U.S. naval and air movements from the north.10 Interestingly, this was not the first time the Aleutians had been identified by Japan as key maritime terrain. Just a year earlier, the Japanese Army had proposed a plan to sever U.S. and Soviet lines of communication by seizing some portion of the Aleutians. Moreover, from a strategically defensive perspective, Japanese planners saw the Aleutians as a potential northern axis of advance on Japan well before the United States had developed the capability to use them as such. After the bombing raid on Tokyo by Lieutenant ColonelLtCol James Doolittle in April 1942, some on the Imperial Staff suspected his B-25 Mitchell bombers had originated from a secret base in the western Aleutians.11

Japan Seizes Key Maritime Terrain

On 5 May 1942, Japanese Imperial General Headquarters issued Navy Order 18 to capture Midway as well as the islands of Attu and Kiska in the western Aleutians. It also directed an air attack on the U.S. base at Dutch Harbor, some 200 miles east of Adak. As Yamamoto’s armada set course for Midway, a smaller Northern Area Fleet under Vice Admiral Hoshiro Hosogaya composed of two light aircraft carriers, six cruisers, a dozen destroyers, and various amphibious support vessels moved east from the Kuriles to attack the Aleutians. The element of surprise was crucial, but U.S. success in breaking portions of the Japanese naval code informed Nimitz in mid-May of Yamamoto’s plan. Buckner’s Alaska Defense Command was duly warned as Nimitz prepared to confront both Japanese fleets simultaneously. While three U.S. aircraft carriers converged on Midway, a smaller force—Task Force 8 under Rear Admiral Robert “Fuzzy” Theobald—raced to the North Pacific to defend the Aleutians.

During 3–4 June, Japanese carrier-based aircraft bombed Dutch Harbor, killing 43 soldiers and sailors, wounding another 64, and damaging infrastructure. The Japanese also destroyed eleven U.S. aircraft while losing ten, including an A6M Zero fighter that U.S. forces recovered largely intact. It was quickly disassembled and shipped to the States, where a complete technical analysis was performed that was later credited with influencing U.S. fighter designs.12 Throughout the two days of attacks on Dutch Harbor, Theobald’s Task Force 8 had remained just south of his headquarters on Kodiak Island, wary of being discovered by Japanese aircraft but frustrated by his inability to locate Hosagaya’s fleet with his PBY Catalina patrol aircraft and help from Eleventh Air Force bombers.

Japan’s crushing defeat at Midway temporarily delayed their planned landings in the Aleutians as the two actions were loosely coupled. However, Yamamoto thought a small naval success would help offset the disaster at Midway, and the defensive value of establishing advanced bases in the western Aleutians remained valid. At the very least, they would bedevil the U.S. Navy’s control of the North Pacific.13 So Yamamoto directed the Attu-Kiska landings to go forward. During 6–7 June, Hosagaya landed 2,500 troops on Kiska and Attu—the first U.S. territory captured by an enemy force since the War of 1812. The landings were effectively unopposed. Once established ashore, Japanese soldiers and sailors set about fortifying positions, building seaplane ramps, and installing antiaircraft batteries. They would later attempt to construct two airfields with little more than hand tools.

America Retaliates

The occupation of Attu and Kiska dealt a serious blow to American prestige. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff directed that the effort to recapture the islands begin as soon as possible. This operation, the first U.S. counteroffensive of the war (preceding Guadalcanal by two months), required a joint littoral campaign whereby a series of advanced bases would be constructed from east to west along the Aleutian Chain, with airfields suitable for heavy bombers situated close to sheltered harbors. The selection of mutually supporting airfields and harbor sites required close cooperation between the Services— a level of cooperation between the Army and Navy that had heretofore proven difficult.

Unfortunately, a unified theater commander for the Aleutian Campaign was never identified, exacerbating already tense command and personal relationships between Buckner and Theobald. In a rare oversight by Nimitz, the respective commanders of the Alaska Defense Command and North Pacific Force were directed to conduct a joint campaign through “mutual cooperation” and share the use of the Eleventh Air Force. Predictably, Buckner and Theobald were never able to set aside their differences and achieve a productive command relationship based on mutual trust and respect, and halfway through the campaign, Nimitz replaced Theobald.14

The campaign was slow to get organized and gain momentum, but Army and Navy engineers prevailed in unimaginably tough conditions, defying the skeptics, and proving essential to the ultimate success of the campaign. Meanwhile, the fledgling Eleventh Air Force mounted a sustained long-range bombing campaign while the Navy prowled the fog-shrouded seas searching for Japanese vessels with the electronic eyes of radar.15 The weather was as much an enemy as the Japanese. Shifting winds, squalls, and low clouds made air operations extremely hazardous, while rough seas and limited visibility made the U.S. naval blockade challenging. Japanese Navy submarines were a constant menace, while its destroyers and transport vessels still managed to periodically slip past U.S. air and sea patrols to resupply and reinforce the garrisons. Japanese forces ashore not only survived the bombardments but also, over the course of the campaign, increased their concentration of antiaircraft guns, redistributed forces between Attu and Kiska, reinforced Attu, defended Kiska with seaplane fighters, attacked the new U.S. airbase at Amchitka, and most importantly continued to deny the Americans a northern approach to Japan.16

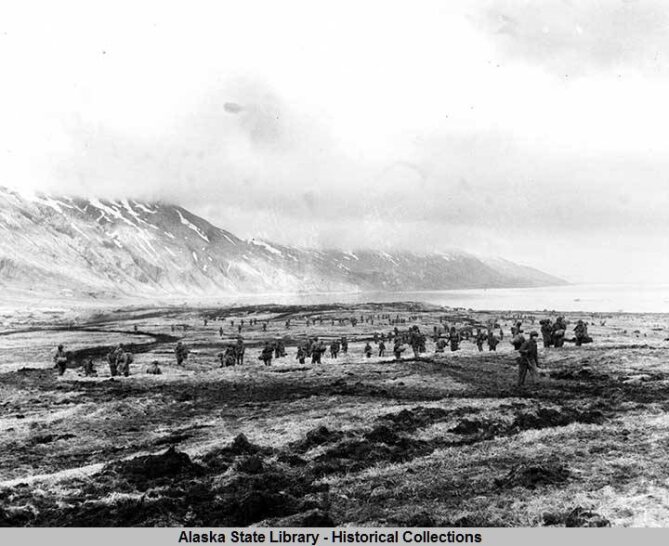

Finally, on 4 May 4, 1943, ten months after Japanese forces seized Attu and Kiska, an American amphibious task force set sail from Cold Bay to recapture Attu. Kiska, the closer and more heavily defended of the two occupied islands, was bypassed for the time being.17 Operation LANDCRAB, the assault on Attu, began on 11 May and was spearheaded by the untested 7thth Infantry Division (7thth ID). Intelligence reports estimated Attu to be defended by a force of 1,600, but a successful Japanese reinforcement effort by fast transports and destroyers in early April had clandestinely raised the number of defenders to over 2,600. (18)

Poor weather and difficult terrain hindered the entire U.S. operation. Dense fog caused at-sea collisions, and mist ashore delayed the multi beachmulti-beach landings and limited the use of naval gunfire. Trucks and artillery pieces became hopelessly mired in the muskeg, causing supplies and ammunition to pile up on the beach and ultimately be carried inland by hand.

Japanese light infantry occupied carefully prepared defensive positions on high ground that dominated the landing beach exits. Concealed from observers below by a protective mist that hovered a few hundred feet above the landing beaches, the dug-in Japanese soldiers could nevertheless see well enough to deliver deadly accurate fire on American soldiers below as they struggled to advance over the wet, spongy ground. By massing indirect fires, the 7thth ID was eventually able to close on the Japanese defenders from multiple points and drive them into a pocket. The last of the Japanese, some 800 soldiers, ended the battle abruptly on 29 May with a vicious banzai charge that overran several frontline formations and a field hospital inflicting horrific casualties before being stopped by a hastily formed defensive line on a promontory known as Engineer Hill.

Only 28 Japanese soldiers survived the Battle of Attu. Burial parties counted 2,351 enemy dead on the battlefield with another three hundred found to have been buried earlier by the Japanese. Of 15,000 Americans in the invasion force (10,000 of whom constituted 7thth ID), 549 were killed and 1,148 wounded in action. Another 2,132 soldiers were evacuated for sickness and severe cold-weather injuries. What was planned as a three-day operation had taken a reinforced infantry division backed by overwhelming air and naval power three weeks to accomplish. The 25-percent casualty rate inflicted on the landing force was only exceeded in the Pacific war at the Battle of Iwo Jima.19

The suddenness and ferocity of the final Japanese banzai charge left a deep impression on one of the few Marines in the Aleutians at the time. Major General MajGen Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, who had overseen the amphibious training of the 7thth ID in southern California, was present as an observer during Operation LANDCRAB. After the banzai attack, Smith made a conscious decision to train specifically for such occurrences in the future.20 He would later credit this experience on Attu with his anticipation of both the time and location of the fanatical banzai attack that would occur in the closing days of the Battle of Saipan a little over a year later.21

The Kiska Surprise

With Attu in American hands, preparations for Operation COTTAGE, the amphibious assault on Kiska, shifted into high gear. Intelligence estimates fixed Japan’s Kiska garrison at around 10,000 men. With the painful lessons of Attu still fresh, American commanders assembled a massive invasion force of 35,000 troops (including 5,500 Canadians) and 100 ships at Adak over the next three months. After weeks of preparatory bombing and naval gunfire, the landing took place on 15 August. It was unopposed. As U.S. and Canadian soldiers ventured inland, they encountered no resistance whatsoever. A cautious but thorough search revealed only abandoned and destroyed Japanese equipment, numerous bunkers, and an extensive network of underground tunnels.

The news that so large a Japanese force had slipped away undetected despite daily bombing and aerial reconnaissance missions—to say nothing of the vastly superior American armada that encircled the island—was greeted with shock and disbelief by nearly all senior leaders. One notable exception was Major MajGen General “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, who, along with some of his staff, had returned to the Aleutians to direct amphibious training for the landing force. He had no direct role in planning the Kiska invasion but remained in Adak as an observer. For two weeks prior to the landing, Smith studied intelligence reports and aerial imagery of Kiska and, recalling how six months earlier approximately 11,000 Japanese troops had quietly slipped away from Guadalcanal on destroyers at night, concluded that the Japanese had already left the island.22 His call for a small ground-reconnaissance element to scout the island before the landing was rebuffed as too risky by the Army’s landing force commander, Major General Charles Corlett, who dismissed Smith as an interloper and would not even show him the landing plan.23 The decision was ultimately left up to Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, the North Pacific Force commander who had replaced the prickly Theobald months before the Attu operation. Kinkaid considered the risk to the scouts greater than to the landing force and directed that the full-scale invasion proceed as planned, even if it turned out to be, in his words, just a “super dress rehearsal, excellent for training purposes.”24

Despite the absence of any Japanese defenders, however, the landings proved far more dangerous than a training exercise. Casualties ashore included 21 men killed and 50 wounded either by booby traps or shot by fellow Americans or Canadians, as edgy soldiers fired at each other in the mist, mistaking adjacent comrades for the dreaded Japanese.25 The last and most serious casualties of COTTAGE occurred when a destroyer, the USS Abner Read, had its stern ripped off by a moored mine in Kiska Cove, killing 70 sailors and injuring 47. (26) In his memoirs, Smith called the failure to allow a proper reconnaissance in advance of the landings an act of inexcusable negligence by senior commanders.27 Kiska was declared secure on 24 August 1942. Operation COTTAGE brought the Aleutian Campaign to an anticlimactic but frustrating end.

Only after the war would Americans learn how a Japanese surface task force, under the command of Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura, had accomplished the evacuation. Kimura had waited patiently for weeks until weather conditions favored an unobservable approach from Paramushir Island in the Kuriles to Kiska. Navigating by dead reckoning in a tight formation under radio silence, Kimura guided his task force through thick fog for a week to slip quietly into Kiska Bay on the afternoon of 28 July. Immediately upon anchoring, Kimura’s task force and the Kiska garrison began the evacuation with remarkable precision and efficiency. In less than one hour and again under complete radio silence, the entire Japanese garrison of 5,183 men was transported by landing craft and loaded aboard six destroyers and two cruisers.28 The Japanese aptly described the evacuation as a “perfect operation”; it was undoubtedly one of the most daring and successful evacuations in military history.29

Echoes of Attu and Kiska in the 21stst Century

While the Aleutian Campaign is rarely examined from the Japanese perspective, the accomplishments and shortcomings of Japan’s forces and methods offer some intriguing lessons and planning considerations for emerging operational concepts such as EABO—particularly in a conflict with a peer adversary such as China. Japan’s operational practices can be instructive for some of the challenges the United States currently faces in the strategic island chains of the Western Pacific. Certainly, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s operational reach, stealth, speed, and tenacity both on and below the surface were critical to the sustainment, mobility, and command and control of Japanese “stand-in forces” conducting a form of EABO in the Aleutians. That Japanese naval forces were able to evade detection, strike Dutch Harbor, seize key maritime terrain, and persist in their advanced Aleutian bases for well over a year was a remarkable feat. The weather conditions naturally helped in this regard. The adverse weather routinely shielded Japan’s most vulnerable assets from American eyes and bombs. At the same time, the Japanese Navy managed to exploit prolonged periods of darkness, fog, and cloud cover to evade U.S. air patrols and run the U.S. Navy’s blockade on several occasions. Japanese successes during the campaign were manifold. They were able to reposition and resupply their forces, deliver reinforcements, conduct seaplane operations, and build a formidable air defense capability. Their evacuation of an entire garrison completely undetected in an incredibly compact time period defies the imagination and remains an unrivaled achievement in the annals of amphibious evacuations under pressure.

Given the ongoing focus within the Marine Corps on light and mobile “littoral” formations, the effectiveness of the Japanese Army’s landward defense of key littoral terrain is also worth studying. Small numbers of well-trained, dispersed light infantrymen were able to attract considerable attention and impose severe costs on a far larger, multidomain task force after it landed on Attu. The defenders’ resilience and tenacity, despite prolonged isolation and severe conditions, were perhaps their most obvious attributes. These attributes remain relevant today, particularly for an isolated force conducting EABO. During the campaign, the Japanese ability to exploit difficult terrain and turn unique weather conditions into an advantage was equally impressive.

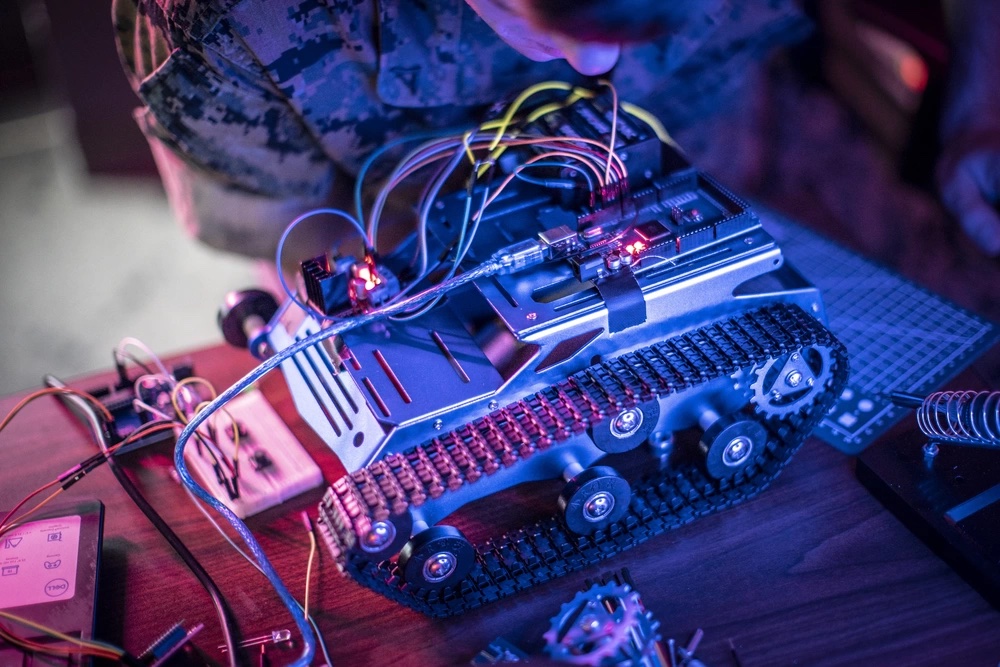

While it might appear that today’s advanced technologies such as long-range precision fires and unmanned aerial vehicles make comparisons between 1943 and the present (or even the near future) problematic, there are capabilities that remain valid for any outnumbered force defending a salient of key maritime terrain. The tactical value of all-weather, suppressive fires; anti-invasion obstacles; antiship weapons; air defense; and over-the-horizon reconnaissance assets is clear; these are enduring requirements for the defense of EABs. Stand-in forces operating inside an enemy’s weapons engagement zone may also require the ability to perform heavy engineering tasks to rapidly build airfields to project power and fortifications to survive sustained attacks. Furthermore, a force executing EABO that can organically emplace maritime sensors and undersea effectors (e.g., sea mines and decoys) to interdict enemy surface and subsurface vessels around vital, littoral chokepoints can contribute asymmetrically to sea denial with virtually no signature. Bringing such effects to bear requires a deep and modular inventory of maritime capabilities from across the naval force to build balanced or specialized task organizations as required.

In many ways, this depth in capabilities was the decisive American strength that eluded the Japanese, who were unable to complete even a single airfield during their year-long occupation of two Aleutian islandsAleutian Islands. Yet their ability to construct fortifications and tunnels dramatically improved their ability to survive bombardments requiring a sizable landing force to dislodge them from the advanced bases they had established. Had their diligence and determination been complemented by such capabilities as long-range radar and engineering, the Japanese would likely have been able to build and operate airfields which would have delayed both U.S. amphibious assaults for many months.

Conclusion

The impact of Japanese forces landing on American soil reverberated all the way to Washington. The political pressure to clear two Aleutian islandsAleutian Islands of fewer than 8,000 Japanese troops drained substantial resources at a dangerous time for the global Allied war effort. The Japanese achieved disproportionate effects against U.S. forces whose strategic objective became increasingly shaped more by emotional sentiment than reasoned assessment. Even when the actual invasion threat to the North American mainland was determined to be minimal, Washington had no strategic patience for any course of action that failed to yield a decisive tactical defeat of Japanese forces in the Aleutians. Thus, the United States adopted an attrition-centric operational approach that culminated in the costly recapture of Attu and, unknowingly, the embarrassing amphibious assault on Kiska nearly three weeks after the Japanese had departed.

In the end, the 15-month campaign drew in over 300,000 Americans, thousands of aircraft, and hundreds of warships, transports, and merchantmen. It also necessitated an immense diversion of military engineering resources to build dozens of U.S. bases and supporting infrastructure where none previously existed—including the 1,640-mile Alaskan Highway across Canada to link the “Lower 48” with Alaska. The heavy commitment of manpower to the North Pacific disrupted mobilization plans and delayed global force deployments to primary theaters for nearly two years. It also forced the U.S. to pour billions of dollars of materiel into a physically taxing and dangerous theater that in the end contributed very little to defeating Japan and hastening the war’s end.

The phenomena and interactions just described will likely be a feature of future wars and again prompt disproportionate, unnecessary, and even reckless decisions by distant political leaders seeking immediate results. The Aleutian Campaign case suggests that, in addition to contributing to sea denial, stand-in forces executing EABO can generate strategic effects by forcing an adversary to divert substantial resources from principal objectives to honor or neutralize the threat the stand-in forces appear to pose. Whether they can succeed in this regard will depend on their location and their attributes. Do they pose a credible and durable threat? Are they resilient, tenacious, stealthy, and survivable? Now, as then, the value of stand-in forces in the face of a regional hegemon will likely be tested. Whether they stand and fight, or slip away in the night, may once again be more a matter of strategy than tactics.

>Col Sinclair retired in 2018 after 30 years on active duty. He is currently a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Emerging Threats and Opportunities at the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory.

Notes

1. Stetson Conn, The Guarding of United States and its Outposts, US Army in World War II Series: The Western Hemisphere (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1964).

2. Brian Garfield, The Thousand Mile War (Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 1969).

3. Guarding of United States.

4. The Alaska Highway was not completed until November 1942. In 1940, there was only one government rail line between Seward and Fairbanks by way of Anchorage.

5. Guarding of United States.

6. Thousand Mile War.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Galen Roger Perras, Stepping Stones to Nowhere: The Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and American Military Strategy, 1867-1945 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2003).

10. Ibid.

11. Japanese Navy General Staff, “Aleutian Naval Operation, March 1942–February 1943,” Japanese Monograph No. 88, trans. Military Intelligence Service Group, G2, Headquarters, Far East Command (monograph, US Department of the Army, n.d.), http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Japan/Monos/pdfs/JM-88_AleutianNavalOperations/JM-88.htm.

12. George L. MacGarrigle, Aleutian Islands, Center for Military History Pub 72-6, (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1992).

13. Guarding of United States.

14. Thousand Mile War.

15. Attu is 350 miles west of Kiska and was initially out of range.

16. Thousand Mile War.

17. Although Kiska was smaller, it was the more militarily important of the two islands with a much larger Japanese force. Attu was selected first both to gain valuable experience and because the number of available amphibious ships could not accommodate a multi-division landing force as was deemed necessary for Kiska.

18. Thousand Mile War.

19. Ibid.

20. Norman V. Cooper, A Fighting General (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Association, 1987).

21. Holland M. Smith, Coral and Brass (Nashville, TN: The Battery Press, 1989).

22. Thousand Mile War.

23. Fighting General.

24. Thousand Mile War.

25. Ibid.

26. Aleutian Islands.

27. Coral and Brass.

28. Thousand Mile War.

29. Masataka Chihaya, “Mysterious Withdrawal from Kiska,” Proceedings 84, No. 2 (1958).