Noncommissioned officers (NCOs) perform one of the most critical functions of the Marine Corps. They serve as the first line of leadership in every small unit and can make or break the officers over them. In combat, the significance of their role expands greatly as they make decisions with immediate impact on the lives of their Marines.

Active-duty personnel and civilians on Marine bases around the world dedicate their full-time efforts to the professional military education (PME) of up-and-coming NCOs. In Quantico, Va., the College of Enlisted Military Education enjoys the benefits of their proximity to the National Museum of the Marine Corps and all the resources it can offer.

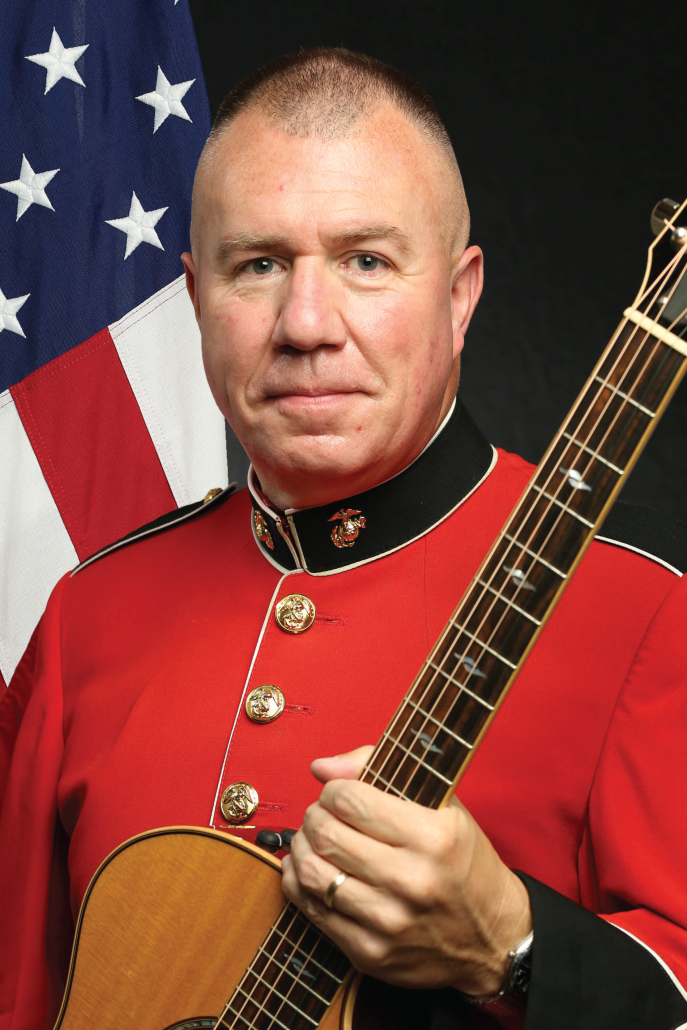

One of the most important resources comes from the experience of docents who volunteer their time to help preserve the history on display and educate the public. Ronald Echols has served as a docent since 2008. He left the Marine Corps as a second lieutenant in 1968 after four years of service. At first glance, his lowly rank and time in service may seem unremarkable, but for those who know him, Ron’s time on active duty proved an action-packed whirlwind of combat, leadership challenges and, ultimately, a battlefield commission. As a result, today he helps lead a portion of the PME for new sergeants during their four-week primary course.

“I try to explain to them that caring for the Marines under them is the most important thing they’ve got to do,” Ron said. “It’s like being a parent. All of them are now in charge of somebody and they’ve got to take care of them. I have the students for about 45 minutes, and it always makes me feel good to feel like I’m giving something to these young Marines.”

Baptism by Fire

Ron joined the Marines in 1964 at the age of 18. He received selection for sea duty and spent two years aboard ship before joining the 2nd Marine Division rifle team at Camp Lejeune, N.C. He made sergeant in less than three years, and in June of 1967, deployed to Vietnam. Assigned to “Mike” Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, Ron endured his baptism through fire in short order. The battalion operated in the northern part of South Vietnam along the Demilitarized Zone. Through the summer, several Marine units were bloodied and nearly wiped out by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) near Con Thien. 3/26 arrived in September for their turn in the melee.

The battle opened on Sept. 7. Ron’s company witnessed their heaviest action three days later.

“We had four tanks, two Ontos, and a battalion of Marines,” Ron remembered. “Who is gonna mess with a battalion of Marines and all that armor? Well, the 324th NVA Division attacked us. Within 15 minutes, we had one Ontos left, and the tanks were blown all to crap. It was raining artillery on us. For seven and a half hours, it was on, with hand-to-hand and everything.”

At one point during the battle, Ron pushed forward with his Marines. A punch to his face temporarily stunned him before he surged ahead again.

“He’s hit!” screamed one of Ron’s Marines.

“Who’s hit?” Ron yelled.

“You’re hit!”

Ron discovered a splash of blood across his flak jacket increasing in size. He put his hand to his face and lowered it covered in red.

“Well, give me a bandage then!”

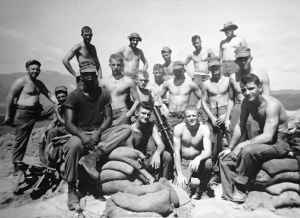

SSgt Ron Echols, left, and one of the Mike Co Navy corpsmen on Hill 881S during the siege at Khe Sanh. (Photo courtesy of Charles McCarty) He continued fighting until the next day when he could be evacuated to the hospital ship. Doctors discovered a bullet entered his cheek near the mouth and exited the other side of his face in front of his ear. Miraculously, no bones or nerves were hit. A plastic surgeon went to work, and less than a month later, Ron returned to the front lines. He counted as one of 434 Marines from the battalion wounded in the fight around Con Thien where 55 had been killed. Due to the attrition his company suffered, Ron was appointed the platoon sergeant. He would hold the responsibility for his platoon for the rest of his time in Vietnam.

The remainder of 1967 proved mercifully less eventful for Company M as a whole. October and November held several significant events for Ron, however. He received a second Purple Heart during one patrol when an ambush caught them with mortar rounds. Shrapnel peppered his leg, but Ron completed the mission without evacuation from the field. Later, on another patrol around a U.S. Navy Seabees gravel operation called “the rock crusher,” Ron further increased his reputation as a bold and decisive leader.

Ron volunteered one morning to take out a recon patrol of eight Marines, in place of a squad leader who typically led the daily tours around the perimeter. As they moved down a dirt road, friendly mortars suddenly exploded nearby over the crest of a distant hill. Ron grabbed the radio as the patrol found cover.

“What the hell is going on?”

“We’ve got a large group of Viet Cong in the open!” Replied a voice on the other end.

“Well, you’re almost on top of us!”

Sprinting figures appeared over the top of the nearby hill, holding AK-47s and heading directly toward Ron’s patrol. More followed behind the lead group. Even more sprinted up and over the crest behind them. Ron moved the radio back to his face.

“I see them! They’re coming over the hill right in front of me!”

“Act as a blocking force!”

Ron laid eyes on the seven other Marines of his patrol. At least five times their number of VC were already over the hill and coming on fast.

“Do you know who you’re talking to?” Ron asked, presuming the voice believed Ron was at the head of a company, or even a full platoon.

“Yes! Now act as a blocking force!”

Ron dropped the radio and ordered the Marines into a ditch alongside the road.

“Stay down! Nobody shoots until I do!”

The first group of enemy stopped alongside the road less than 20 yards away. They waited in the open as more VC poured over the hill. Within minutes, a group nearly 50 strong gathered by the road catching their breath.

“I swear to God, I do not know what made me do this,” Ron remembered recently. “I jumped up and shouted, ‘Stop!’ in Vietnamese and every one of them threw their hands straight up in the air. The only thing I can figure is that they had just gotten through being mortared like crazy and they thought they had run into some big unit, so they surrendered.”

The Marines led the group of prisoners to an open spot in the road and surrounded them as they lay on the ground. Ron radioed for immediate help. The closest available unit was a group of Australians.

“I don’t care who they are,” Ron advised. “We need help now!”

A dust cloud soon formed in the distance as a convoy of Australian vehicles approached. The Aussies tucked prisoners into every nook and cranny of their trucks to transport their haul away. The Marines moved aside as the convoy sped off. As the engines faded into the distance, Ron turned to his stunned men.

“This patrol is OVER!”

They returned to base safely and found the platoon commander and company commander waiting for them inside the wire.

“Sergeant Echols,” said the captain, “You come with me.”

The officer immediately filed paperwork for Ron’s meritorious promotion to staff sergeant. Less than three weeks later, with just over three years total in the Marine Corps, Ron received his promotion to staff sergeant. After Ron’s elevation to platoon sergeant, several new lieutenants cycled through. Some were wounded, some were fired, but either way, the end result left Ron ultimately responsible. He excelled in his role as acting platoon commander to such an extent that existing and incoming officers deferred to him, and left Ron in charge of his platoon.

By the end of December 1967, 3/26 received orders to support the looming conflict at Khe Sanh. Ron and the Marines of Company M occupied a front-and-center role in the siege, positioned west of Khe Sanh Combat Base on Hill 881 South.

“That wasn’t some training evolution, that was a real firefight,” SSgt Ron Echols said recently. “If I would have known at that time he was taking a video, I’d have grabbed that camera and stuck it where the sun don’t shine!” Courtesy of Charles Martin.

Marine defenses on 881S spread across two distinct hill tops, separated by a low saddle in between. Company I, 3/26, occupied the higher hilltop. Two platoons from Mike took over the lower side. Ron arrived with his Marines and found basic defensive positions carved out of the hill by its previous occupiers. He immediately ordered his Marines to dig deeper. They placed multiple layers of concertina wire outside the trench line, designed to funnel any oncoming enemy into the Marines’ machine guns. Ron directed his platoon to complete their defensive barriers with a tall, barbed wire fence immediately outside of their trench line, preventing any approaching enemy from jumping into the trenches. The Marines spaced mines and claymores around the entire perimeter. When they ran out of claymores, Ron found an abundance of detonators remaining. He improvised by filling empty ammo cans with spent rifle brass and explosives lining one side, then connected a detonator as a homemade anti-personnel device. Ron directed his men to save their empty C-ration tins and place several small rocks inside. The lid was then bent over a strand of the perimeter wire, creating a noise-making early warning device.

“I don’t even remember who our platoon commander was, but I remember Ron” said Charles McCarty, Ron’s radioman for the duration of the siege at Khe Sanh. “He was doing everything a platoon commander would do. There was this old comic book character called, ‘Sgt Rock,’ and that’s what we used to call Ron, because he was hard as a rock.”

As days turned into weeks on the hill, the trench line surrounding Mike Company evolved from a shallow ditch to a six-foot-deep channel, lined with sandbags and bunkers dug underground. Ron insisted on underground shelters, as their position proved a favorite target of NVA artillery and rockets.

Incoming of some sort hit 881S every day. Snipers kept the hill continually under fire and observation. Another hill less than a mile away, designated 881 North, acted as a NVA stronghold and observation post. Nobody knew exactly what enemy strength 881N housed. Marines patrolling that direction suffered numerous casualties without successfully reconnoitering the hill, included a company-size movement by Company I on Jan. 20, 1968. The Marines on 881S became increasingly exhausted under the constant threat of attack.

U.S. air power afforded the garrison its best chance of survival. The Marines called in air strikes on any suspected enemy position. On one occasion, a sniper harassed Mike Co for several days. Finally, Ron had enough. He grabbed a pair of binoculars and kept watch over the area where the rounds originated until, finally, incoming shots gave away the sniper’s position. He found the sniper perched high in the fork of a tree branch.

“Ron saw him and he says, ‘well, I can take care of that,’ ” remembered Charles Martin, a squad leader in Ron’s platoon. “Ron called in jet. That thing circled the tree one time and came in from the back side. The sniper was climbing down when a bomb hit the base of the tree and blew it in a million pieces.”

A ridgeline several hundred meters away from 881S proved a continual source of incoming NVA artillery and rifle fire. The ridge was close enough that individual enemy soldiers were easily seen moving around. Despite its close proximity, B-52 “Arc Light” strikes rained down continuously across the ridge.

“Have you ever seen video of an arc light?” asked Charles McCarty. “To this day, when I say the word, ‘arc light,’ I get chills.”

Marines who knew what to look for might spot contrails high in the sky, signaling the coming devastation. For those unaware, the bombs fell out of nowhere. A line of explosions suddenly plumed up at one end of the ridge and worked their way across. As the explosions continued, the sound of the falling bombs, followed by their explosions, reached the Marines in a deafening roar. Shockwaves tossed the hill beneath the Marines like an earthquake. Finally, after three B-52s emptied their bomb bays of nearly 30 tons of ordnance per aircraft, nothing but a barren landscape remained.

“B-52s hit that ridgeline every day,” remembered Ron. “They told me on the radio to have the men get in the bunkers, put their fingers in the air, and hold their mouths open. They hadn’t dropped one that close to friendly troops before. I cannot begin to describe the noise. The whole hill was shaking like we were on a ride at the fair or something. There were big rocks falling out of the sky and I thought someone would be killed. It was just unreal.”

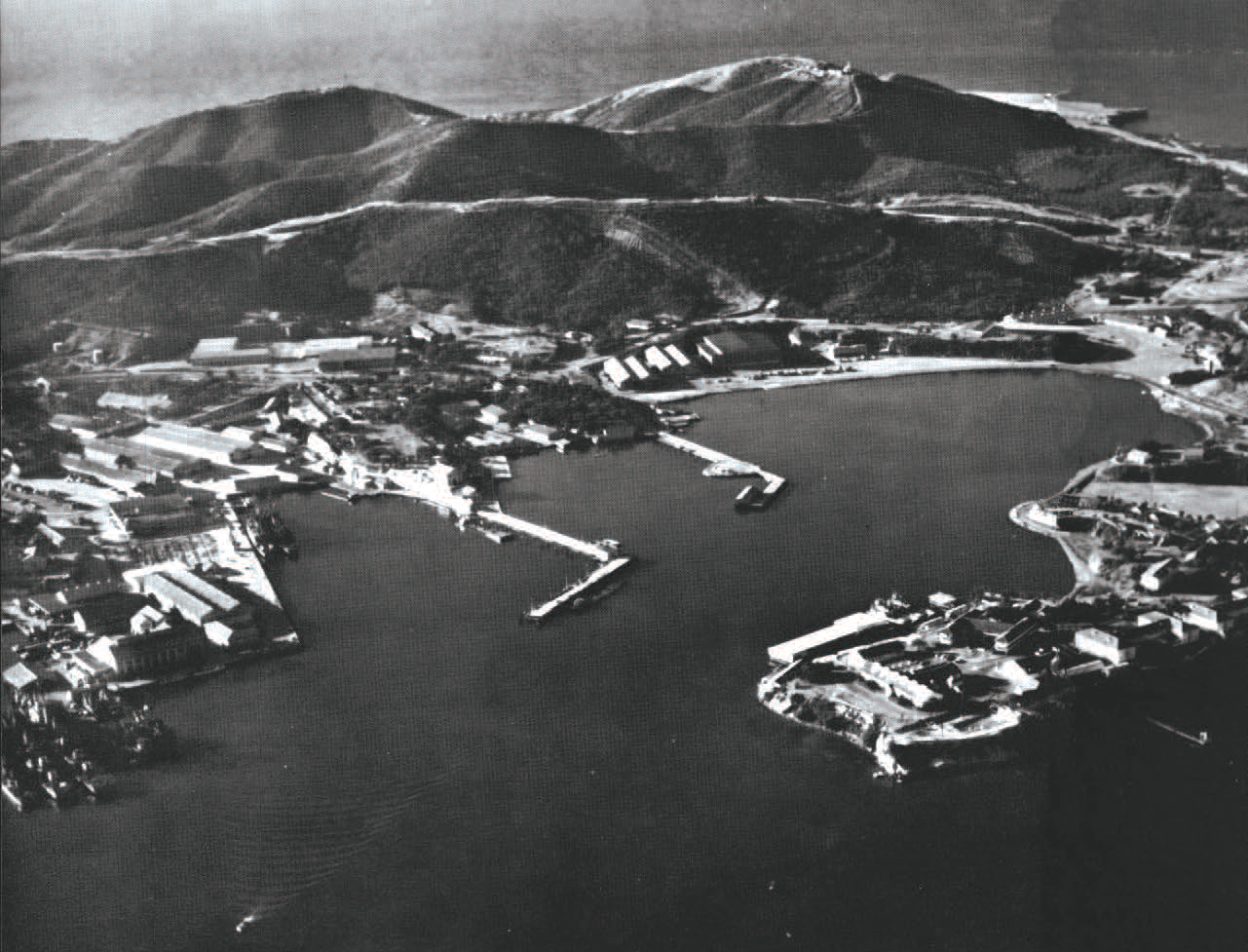

USMC History Division.

Despite the impressive show of air power, the NVA dominated the hills and jungle surrounding Khe Sanh. Hill 881S was inaccessible by land and could only be resupplied by helicopter. The NVA shot down several choppers attempting to resupply the Marines on 881S. Even so, the brave helicopter pilots, primarily from the “Purple Foxes” of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 364, continued coming. Eventually, a “super gaggle” of jets and attack helicopters proved necessary to strafe and bomb the surrounding jungle to cover the resupply choppers. The enemy threat, combined with daily fog and inclement weather, often prevented the Marines from obtaining the critical supplies they needed.

Harry W. Jenkins arrived at 881S as the new captain in charge of Company M, in March 1968. Jenkins, who later retired as a major general, was shocked by the conditions on the hill yet impressed by the level of morale and preparedness maintained. Dirty and bearded Marines in tattered clothing filled the trenches. He found several Marines with visibly decayed teeth.

“I asked the Marines where their toothbrushes were,” MajGen Jenkins said. “They told me they were using them to clean their rifles. Under the circumstances, I couldn’t argue. That’s just one minor example, but things like that led to emergency resupply orders for any number of things. I just couldn’t believe it. We had astronauts in space going around the moon, but we couldn’t get toothbrushes to 881 South.”

Ron rationed food and water among his platoon as critical supplies ran short. At one point, the Marines ran out of C-rations and went for nine days without food before a resupply finally made it into the hill. They spread tarps out over the ground each night, capturing the morning dew to save as drinking water. A mountain stream north of the hill tantalized the Marines. The flowing sounds carried up the slope, but an unknown number of enemy in a parallel trench line stood between Mike Company and the water.

One day, while walking the perimeter, Ron heard movement outside the line, coming up the south slope. He shouldered his shotgun and prepared to fire. At the last second, three Marines appeared through the brush carrying full canteens. After Ron scolded them for being outside the wire and almost getting themselves killed, the Marines explained that they discovered a spring in a gully down the hill, where they had filled their personal canteens. Ron informed them the following day, they would be going back down to the spring with the rest of the platoon’s canteens to draw water for everyone else.

By April, Marines on the hill grew exhausted. Lack of sleep, lack of supplies, and isolation pushed them to the brink. Continual bombardment by the NVA, without real opportunity to retaliate, created a high level of aggression. On April 14, 1968, Easter Sunday, the Marines of 3/26 got their chance to let their aggression out. The order arrived to finally oust the NVA from 881N. Ron’s platoon advanced alongside Marines from Company K, down 881S to the base of 881N. A furious bombardment preceded their attack. Direct fire from 106 mm recoilless rifles on 881S soared overhead as the Marines advanced up the hill. Ron prayed none would fall short into the advancing Marines. The fight ended quickly. Six Marines died in the effort to take the hill. More than 100 NVA bodies littered the abandoned enemy emplacements. An American flag flew over 881N long enough to signal the victory to those observing from 881S, before the Marines backed down the hill once more and choppered out to Khe Sanh Combat Base. This Easter assault marked the end of the siege for Mike Co.

The battalion received a short respite following Khe Sanh. All too quickly, though, they returned to the front lines, attacking into a place ironically called, “Happy Valley,” deep into the mountains Southwest of Da Nang during Operation Mameluke Thrust. The enemy remained determined to send Ron home in a body bag.

During one patrol in their new area of operation, Ron’s platoon walked through chest high elephant grass. They spotted movement in the grass and Ron called the Marines to a halt. As everyone took cover, Charles Martin moved slowly around to a hill on the other side of the suspicious area and began working his way back. Ron gave hand signals directing Martin down the hill toward the area as he crept up from the opposite direction.

Throughout his time in Vietnam, Ron’s weapon of choice was a pump-action shotgun. He shouldered it now once again as he approached Martin. Three Vietnamese soldiers suddenly popped up out of the elephant grass between Ron and Martin. One took off sprinting away from the Marines. Another opened fire at Martin. Martin unloaded a few rounds before a bullet knocked him off his feet. He fell to the ground gasping for breath.

Ron squeezed hard on the shotgun’s trigger and pumped the forestock as fast as he could, instantly emptying seven shells into the grass. He rotated the gun on his shoulder and loaded more shells into the magazine tube. As he slid in a third shell, an enemy soldier appeared out of the grass with rifle raised. Ron shot him down, then continued up the hill.

“I could hear Ron running up the hill after he shot two or three more times saying, ‘Marty, don’t die on me, damn you! Don’t you die on me!’ ” Martin remembered today. “He came up there and rolled me over and slapped me and said, ‘Are you OK?’”

A quick evaluation revealed the bullet tore a hole through Martin’s flak jacket but missed his abdomen. One enemy soldier escaped, and one lay badly wounded in the leg. The Marines found the third soldier dead in the grass, ripped apart by Ron’s initial volley of shotgun blasts.

On May 29, Company M choppered into a newly cleared landing zone (LZ) in the mountains. Ron boarded one of the last CH-46s to depart with 11 Marines from his platoon.

“Once we land, ya’ll need to get the hell off here!” the crew chief screamed to Ron over the noise of the engines. “We’ve been taking heavy fire up there all day!”

As the helicopter approached the LZ, enemy bullets punched holes through the aluminum skin. Hydraulic cables across the entire roof of the interior caught fire and the bird plummeted towards the ground. Tons of small arms and mortar ammo brought in by previous flights remained staged in the LZ. The doomed chopper crashed directly into it and rolled on its side. Ammo began cooking off around the burning wreck. One Marine on the ground near the LZ was killed by flying pieces of the helicopter. Shrapnel stung across Ron’s back, but miraculously, he and all seven of his Marines survived the crash and exited the chopper before it exploded.

Well-Deserved Commission

Official recognition of Ron’s role as a platoon commander finally came through in the last month of his deployment to Vietnam. In the weeks following Khe Sanh, Capt Jenkins submitted the paperwork for Ron to receive a battlefield commission. This distinguished achievement proved exceedingly rare during the Vietnam War. Numerous outstanding NCOs were plucked from combat and sent home to attend Officer Candidates School and The Basic School as part of the Meritorious NCO Program. Others received a temporary commission that reverted at the conclusion of their deployment. An incredibly select few, however, skipped these training steps of the commissioning process, remained in combat, and retained their commission as a permanent rank. Some famous names, such as the legendary Force Recon Marine Major James Capers Jr., are included in this tally. The rest are Marines such as Ron Echols, whose names, reputations, and combat exploits are known only to the Marines with whom they served.

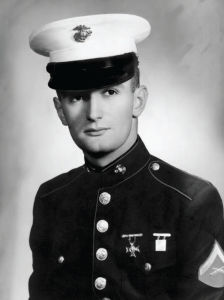

In June 1968, Ron was called out of the field to receive a physical. Wondering why a physical was so important to call him away from his platoon, Ron was informed a physical was necessary for his promotion. In short order, the officers over Ron removed his staff sergeant chevrons and replaced them with the gold bars of a second lieutenant. The fact that Ron’s date to leave Vietnam drew near mattered little. The promotion formally recognized the position he had held all along, through all the trying times his Marines endured.

Ron arrived back in the States the following month. Just four years earlier, he stood on the yellow footprints at Parris Island as a recruit. Now, he faced the end of his enlistment as a battlefield-commissioned officer with a combat distinguished Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts. A third Purple Heart for injuries received in the helicopter crash never came through. With a lifetime of experience far greater than his age of 22 might let on, Ron elected to leave the Marine Corps. Mentally, he had had enough.

Like many Vietnam veterans, Ron dove into civilian life after leaving the military and it was years before he reconnected with the Marines he fought beside. In the early 1990s, Ron began attending 3/26 reunions, and continues to this day. As he reflected back to his time in Vietnam, Ron realized his biggest regret; through all the combat and harrowing situations he and his Marines faced, he had never found the time to recommend any of his brave men for the awards they deserved for their heroism.

In 2007, the reunion group met at the National Museum of the Marine Corps shortly after it opened the previous November. The veterans of Khe Sanh found themselves transported back in time and airlifted to their old positions in the immersive exhibit dedicated to 881S. The mural surrounding the CH-46 ramp recreated the hill with stunning accuracy, and Ron could immediately look down to Mike Company’s side of the hill and point out where his bunker had been, and where some of his comrades had died.

“There is no question that there are Marines alive today thanks the superb leadership and attention to duty displayed by Ron Echols under the most trying conditions,” said MajGen Jenkins today, who also attended the 2007 reunion. “He clearly is one of the best combat leaders I ever served with. Some of that experience is passed on today, as he is often called upon to speak to classes of NCOs and enlisted Marines in various courses at Quantico.”

A Lesson in Leadership

Ron began volunteering at the museum in 2008. He and other docents began their work with the Sergeants Course at Quantico several years ago.

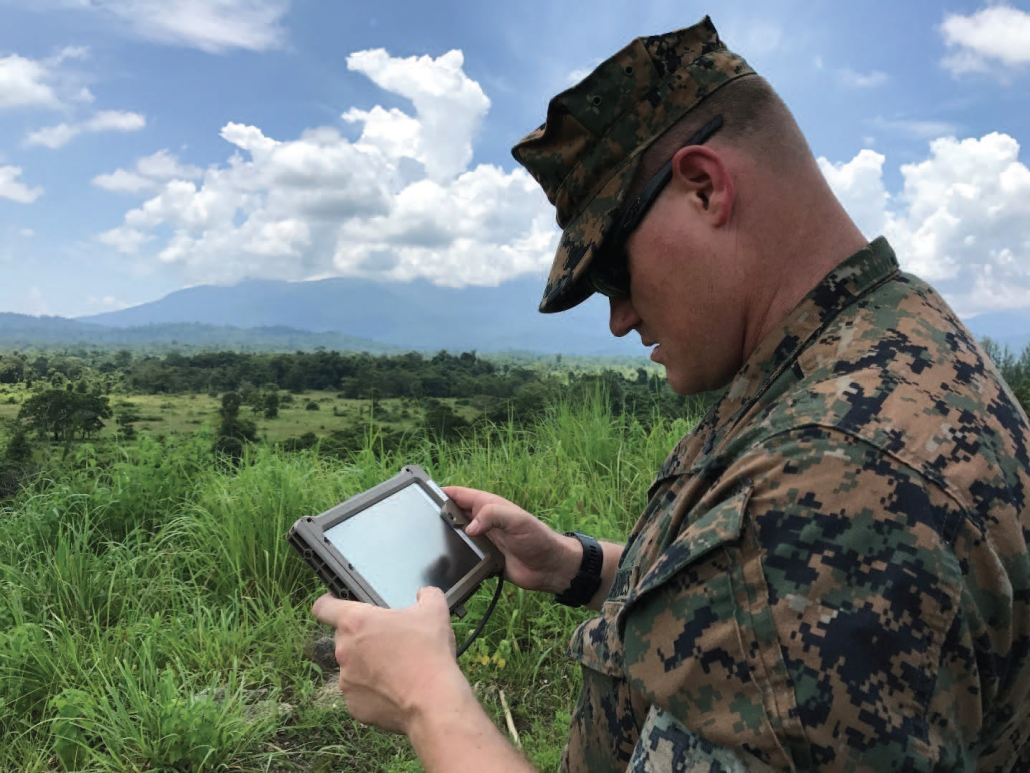

“Going to the museum is not technically a part of our curriculum, but by proximity, we take advantage of the museum and take the students over there,” said Master Sergeant Christian Tetzlaff, the staff noncommissioned officer in charge of the sergeant’s course in Quantico. “The docents are always energetic to help, and they take the opportunity to tell the students about events from their experience and background. Students are pretty impacted by them. It’s real stories from real people who are from their heritage.”

The museum tour comes during the “heritage” portion of the four-week long course. The curriculum covers battlefield case studies on places like Inchon and the Pusan Perimeter from the Korean War. The trip to the museum provides students with a more tangible understanding of the events covered in the classroom. Anywhere between 30 to 70 new sergeants reap the benefits offered through museum and the docents’ class. They begin with Ron in the theater, where Ron walks them through his time on 881S, and what it looks like to work “tirelessly to ensure the safety and well-being of his men,” as is stated in his Bronze Star citation read aloud to the class. The students then proceed to other docents stationed around the museum to learn more from their experiences.

“For sergeants, this course is really about reinvigorating their core values,” said MSgt Tetzlaff. “They are still sponges, trying to figure out what the Marine Corps is really all about and if they’re staying for the long haul. They see representatives like the docents who have no real reason to keep coming to the museum and volunteering their time, other than the fact that they are proud of what they are a part of. Demonstrating that to these young Marines, they’re going to look at these guys and think, ‘they are so passionate, and so thankful for all their experiences,’ knowing that they have experienced tough times,” Tetzlaff said.

“These interactions at the museum are not little things. They are profound moments that embody our culture of, ‘once a Marine, always a Marine.’ A lot of young Marines might look at that and think it’s just a cliché, but then they see it in action and see these docents volunteering their life to serve the betterment of the Marine Corps and keep our heritage alive. There is a lot of opportunity for reflection.”