Physical Fitness

Physical Fitness

“Even the bravest cannot fight beyond his strength.”

– Homer

The Marine Corps Physical Training Program

Purpose and Philosophy

As professional warrior-athletes, every Marine must be physically fit, regardless of age, grade, or duty assignment. Fitness is an essential component of Marine Corps combat readiness. Furthermore, physical fitness is an indispensable aspect of leadership. The habits of self-discipline and personal commitment that are required to gain and maintain a high level of physical fitness are inherent to the Marine Corps way of life and must be a part of the character of every Marine. Marines who are not physically fit are a detriment and detract from the combat readiness of their unit.

The core of the Marine Corps Physical Fitness Program (MCPFP) and key to its success is the Force Fitness Instructor (FFI), assigned throughout the total force down to the company and squadron level, with the end state of optimizing the physical fitness of their unit, and creating a more knowledgeable and capable force. The FFI will serve as the commander’s subject matter expert (SME) on nutrition, physical fitness, and injury prevention. The FFI will advise the commander on the design and implementation of a structured physical fitness training program that is uniquely tailored to the unit’s Training and Exercise Employment Plan (TEEP). The FFI will assess and baseline the physical fitness of the unit and individual Marines and design a comprehensive program to facilitate progressive improvement. The FFI will also facilitate integration of resources such as the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP), the Marine Corps Water Survival Training Program (MCWSTP), Semper Fit, High Intensity Tactical Training (HITT), strength coaches, and Navy medicine to support the commander’s physical fitness training objectives and unit mission.

Components and Principles of Physical Fitness

There are many ways to define fitness. Oftentimes the definition will depend on the goals of a particular program. For the Marine, the obvious goal is combat preparedness. As such, training must focus on preparation for the unforeseen and unforeseeable requirements of combat. To capitalize on the components of physical fitness that can benefit training efforts, the following categories of exercises should be included in both individual and unit physical training programs:

- Cardio-Respiratory Endurance. Cardio-respiratory endurance refers to the efficiency with which the body’s circulatory and respiratory systems deliver oxygen and nutrients needed for sustained physical activity. The two types of endurance training needed for a Marine to meet the physical demands of combat are aerobic and anaerobic.

- Aerobic activity, meaning “in the presence of oxygen,” is categorized by physical demands that are sub maximal and continuous in nature (lasting more than three to five minutes). Examples of aerobic activity are road marching and long distance running.

- Anaerobic activity, meaning “without oxygen,” is categorized by physical demands that are high intensity and of shorter duration (lasting less than two to three minutes). Examples are most forms of weight lifting and sprinting.

- Muscular Strength. Muscular strength is the greatest amount of force any given muscle or group of muscles can exert in a single effort. Muscular strength is often associated with training with weights or machines. To the contrary, however, a Marine’s ability to effectively handle his body weight must be prerequisite to integrating resistive exercises using weights or machines. Strength training can be broadly separated into two categories, general and specific.

- General strength training strengthens the entire muscular system by focusing on a full body workout. In this type of training, muscle groups are exercised without a specific task or functional goal in mind. General strength training contributes greatly to combat preparation and overall health.

- Specific strength training strengthens individual muscles or groups of muscles by focusing on a specific task. In this type of training, individual muscles or muscle groups are exercised in isolation. Specific strength training may be useful to assist in preparation for particular martial tasks. For example, Marines desiring to climb a rope better would climb ropes while wearing body armor and focusing their training on only those muscles involved in rope climbing.

- Muscular Endurance. Muscular endurance is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to perform repeated movements at a sub maximal effort for a sustained period of time.

- Stamina. Stamina is defined as the body’s ability to process, store, and deliver energy throughout a period of prolonged, stressful effort.

- Power. Power is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to apply force rapidly. Mathematically, power is expressed as a work/time ratio. For example, a Marine climbing a wall takes an abnormally long time to elevate his body to the second deck. On the other hand, a Marine climbing stairs elevates his body the same distance in a short amount of time. Both Marines have done the same amount of work, yet the Marine climbing the wall has a lower power rating than the Marine opting to take the stairs.

- Speed. Speed is the ability to minimize the time it takes for the body to execute a movement.

- Coordination. Coordination is the ability to combine a series of different movements into one movement pattern.

- Agility. Agility is the ability to perform a series of movements in rapid succession and in opposing directions.

- Balance. Balance is the ability to control the body’s center of gravity while either stationary or in relation to the movement of its base.

- Flexibility. Flexibility is a joint’s ability to move freely through a full and normal range of motion. During such movement, a muscle or group of muscles will relax, stretch and lengthen.

- Nutrition. Nutrition is the makeup of the individual’s daily caloric needs in relation to operations, physical training and performance.

Because of the unique nature of the Marine Corps’ mission, physical training must prepare the individual Marine to maintain a high level of fitness throughout the length of his career. There are several different principles of physical fitness to consider when developing an effective physical training program:

- Progression. The intensity (how hard) and duration (how long) of exercise must gradually increase over a period of time in order to maximize potential gains and minimize the risk of injury.

- Regularity. Regular exercise, rest, and sleep are vital to a healthy body. There are no easy or occasional methods to develop fitness. Individuals must exercise regularly in order to achieve the desired training effect. Daily exercise is preferred and encouraged. Regularity is not only a vital aspect in exercise, it is important in recovery and diet. The lack of regular exercise, rest, and proper nutrition can do more harm than good. To realize any training effect, programs must be conducted at least three times per week.

- Overload. Overload is the basis for all exercise training. In order for physical fitness to improve, exercise must exceed the body’s normal workload. Unless the body is taken beyond its “comfort zone” by running either faster or longer, or putting more workload on the muscles, then physical fitness will not improve. Only when the various systems of the body are overloaded will they become able to handle greater load.

- Variety. Providing a variety of training reduces boredom and increases motivation and progress. The most successful programs usually include conditioning activities, competitive events, and military physical skill development. Physical training should emphasize unit and fitness training, rather than training solely for the physical fitness test (PFT).

- Recovery. Recovery is the most important principle of physical fitness. Gains from physical training are realized during recovery. There are two types of recovery—active and passive. A moderate to light training day, following a hard training day, is an example of active recovery. Days off during a training cycle are examples of passive recovery. Too many days or weeks of high intensity training can inadvertently lead to overtraining and injury. Recovery is essential for allowing the systems overloaded during training to adapt and become stronger.

- Balance. To enhance its effectiveness, a program should include activities that address all fitness components equally. Programs that overemphasize any single component has the potential to suppress other components. Examples of overemphasizing a single component of fitness may be found within the weight lifter or long distance runner communities. Many weight lifters lack cardio-respiratory endurance and many long distance runners lack muscular strength. Balanced training programs ensure that all the components of physical fitness are properly addressed.

- Specificity. Training that is specific in nature yields specific gains. For example, a fitness goal of “getting in shape” is non-specific; rather, a more particular fitness goal would be “getting in shape by improving cardio-respiratory endurance (through running, swimming, aerobics) and muscle tone (by reducing fat through proper eating habits and weight lifting).” Nevertheless, physical training programs must contain specificity, while remaining cognizant of balance.

- Synergy of Training. Properly designed physical training programs develop a high level of physical fitness, mental toughness and discipline throughout the unit, while simultaneously building character and leadership within the individual. Training in this manner enhances the synergy of the mind, body, and spirit of the Marine.

Phases of Daily Physical Training

Every physical training evolution should flow in the following sequence: dynamic warm-up, abdominal and lower back core strength training, conditioning event, cool-down, flexibility training, and recovery.

- The dynamic warm-up exercises facilitate gradual distribution of blood flow to the muscles, preparing both the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems for the exercise session. The increased blood flow to the muscles produces a warming effect, increasing the elasticity of the muscles and connective tissue. This effect is believed to produce fewer injuries than preworkout static stretching alone.

- Core strength development is crucial for combat fitness. Marines often train the abdominal region but not the lower back, leading to lack of muscular balance and resulting injury. Core specific strength training ensures balance and an increase in core strength. Core strength training may be conducted either before or after the conditioning event.

- The conditioning event is whatever physical training exercises, circuit training, cross training, or agility training that has been selected as the individual’s or unit’s workout of the day.

- The period immediately following the conditioning event is known as the cool-down. Much like the dynamic warm-up prepares the body for an exercise session, the cool-down facilitates a gradual relaxation in which an individual’s heart rate is designed to decrease.

- By incorporating frequent flexibility training, a Marine prevents injuries, increases his natural range of motion and increases the flow of blood to muscles. The benefits of flexibility training far outweigh the alternative. If need be, the training event should be reduced by 10 to 15 minutes in order to facilitate proper and comprehensive flexibility training. There are several flexibility training techniques and methods that are applied to combat conditioning.

- 1. Active stretching occurs when the only force required to conduct the stretch is supplied by the individual. For example, if an individual raises his leg to the front as high as possible, agonist muscles (hip flexor and quadriceps) are supplying the force of the stretch while antagonist muscles (glutes and hamstrings) are stretching.

- 2. Passive stretching involves the use of a partner or device (belt, rope, or towel) to provide force for the stretch. Using a passive stretching device is both an excellent and efficient means of conducting flexibility training.

- 3. Static stretching is the most convenient method of stretching. The method refers to the constant tension being held at the end position of the stretch. The amount of time spent in the end position of a static stretch should vary from 30 to 60 seconds. The only requirements for static stretching are proper form and technique.

- 4. A dynamic stretch is one that involves mimicking the range of motion that will be required to conduct the conditioning event. Specifically, dynamic stretching uses movement specific to the activities about to be performed. Marines may use this type of stretching to prepare for calisthenics or obstacle course evolutions. For example, prior to obstacle course training, Marines performing slow, full range of motion high stepping to the front and laterally may prepare their respective muscles for leaping and bounding over obstacles.

- 5. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) is considered the gold standard of flexibility training. Throughout PNF stretching, the same or opposing muscles contract and relax. This causes a neural response that prevents the contraction of the muscle being stretched, resulting in reduced resistance and increased range of motion. An added benefit to PNF stretching is that this method can increase one’s muscular strength due to the isometric or concentric contraction of the muscle being stretched. PNF stretching is best done with the help of a partner; however, a passive stretching device will work as well. PNF stretches should be held for 30 to 60 seconds.

- 6. Ballistic stretching uses bouncing movements in which a joint’s range of motion is moved beyond normal limits. As such, the muscle or group of muscles is not stretched and held at its end position. Ballistic stretching is the least desirable form of flexibility training for Marines due to its tendency to damage and injure the muscles and surrounding tissues. Irregularly bouncing, jolting, and snapping movements may damage muscles and joints and should generally be avoided.

- Again, gains from physical training activities are realized during the recovery phase. Recovery will last from the last repetition of the current conditioning event until the first repetition of the next conditioning event.

Physical Training Circuits,

Cross Training, and Agility Training

Physical training circuits should be developed with designated stations that encompass combat conditioning agility training, exercises, and standard martial tasks. For example, a station based drill on the LZ filled with various exercises and martial arts techniques would include each of the functional areas of combat conditioning circuit training.

Cross training consists of multiple exercises performed in a specific order that will significantly affect the body. These cross training events can be highly varied, short in duration, and very intense, promoting a high fitness level among Marines and ideally preparing them for the unexpected rigors of combat. For example, three rounds of 10 buddy squats, 15 pull-ups, and a 400-meter run would take a relatively small amount of time to complete; however, it would likely produce a relatively high degree of intensity.

Agility training assists in the development of coordination, or the ability to maneuver on the battlefield. This may be accomplished by incorporating cone drills, agility ladders, and mini-hurdles. Additionally, training may be integrated into immediate action drills, command and control drills, fire and movement drills, and bayonet engagements.

Physical Conditioning Exercises

The exercises depicted are divided into five categories: individual conditioning exercises, buddy exercises, buddy carries, movement exercises, and strength training exercises. These physical training events/exercises can be completed with minimal equipment by any Marine anywhere and are not necessarily inclusive of all equipment and methods that can be used to develop physical capacity.

- Individual conditioning exercise includes core strength conditioning and calisthenics. These exercises are designed to increase the Marine’s level of fitness, using only the Marine’s body weight.

- Buddy exercises include calisthenics, core strength conditioning and stabilization exercises that, in order to be conducted, require a partner. Buddy exercises are designed to increase teamwork, as well as provide additional weight or resistance during exercises in order to increase the muscular strength and endurance required to accomplish martial tasks.

- Buddy carries and movement exercises are designed for movement on the battlefield while under fire, moving to the objective or while evacuating a casualty to cover or an aid station. These movements may be executed individually or as a squad.

- Strength training exercises are important in providing Marines with a rounded physical training program, while providing skill transfer for martial tasks. These strength training exercises focus on the use of austere equipment rather than weight training as one would find in a gym.

- 1. Weighted ammo can or five-gallon water can training provides a means of strength training for operational units. Both types of cans are easily deployed and cost effective. Moreover, if cans cannot be obtained, sandbags, bricks, large rocks, and similar items may be used as well. In addition to fighting, Marines should be capable of training in every clime and place.

- 2. Sandbag medicine ball training also provides skill transfer for martial tasks, while potentially increasing one’s range of motion and strength. Single sandbags filled with varying amounts of sand, shaped appropriately, and duct taped will provide field expedient medicine balls that can be used in garrison or in the field.

- 3. Sandbag kettlebells are performed with one-half to three-quarters full sandbags that have been formed with a handle to represent a kettlebell. Training with sandbag kettlebells will help develop strength, power, and explosiveness.

When programming drills, circuits, or routines, trainers must have an understanding of the body’s movement during a particular exercise. The four basic movements include pushing, pulling, overhead, and squatting. Drills and routines must be designed in a specific order. For example, four pushing movement exercises executed in a row greatly increases muscular fatigue and are not ideal in most situations. Most routines should alternate between pushing and pulling, overhead and squatting movements. This emphasizes the principle of balance by alternating working muscle groups and provides specific muscle groups a brief period of recovery. Additionally, alternating movements tends to intensify the workout by making the body work harder to send blood and oxygen to multiple muscle groups throughout the body during a routine.

There are three categories of exercise that assist in programming workouts. The first category of exercise is weighted, in which any weight other than the body is used during the exercise. Examples of weighted exercises include buddy squats and sandbag swings. The second category of exercise is body weighted, in which only one’s body weight is used during the exercise. Examples of body weighted exercise include push-ups, pull-ups, and body squats. The third category of exercise is aerobic, in which the focus of the exercise is aerobic conditioning. Examples of aerobic exercises include running, swimming, hiking, and rowing.

An Assortment of Physical Conditioning Exercise

Illustrations and Descriptions

Core Strength Exercises

Front Plank. This position can begin from any of the side plank or front leaning rest positions. The Marine will begin on the elbows while keeping the upper arm perpendicular to the torso creating a 90 degree angle. (See Figure 9-1.) Once in this position the Marine will suck the stomach in and keep the back straight. The hips will remain up and in alignment with the shoulders; the head will be in a neutral position. (See Figure 9-2.) The exercise will be held for a specified time.

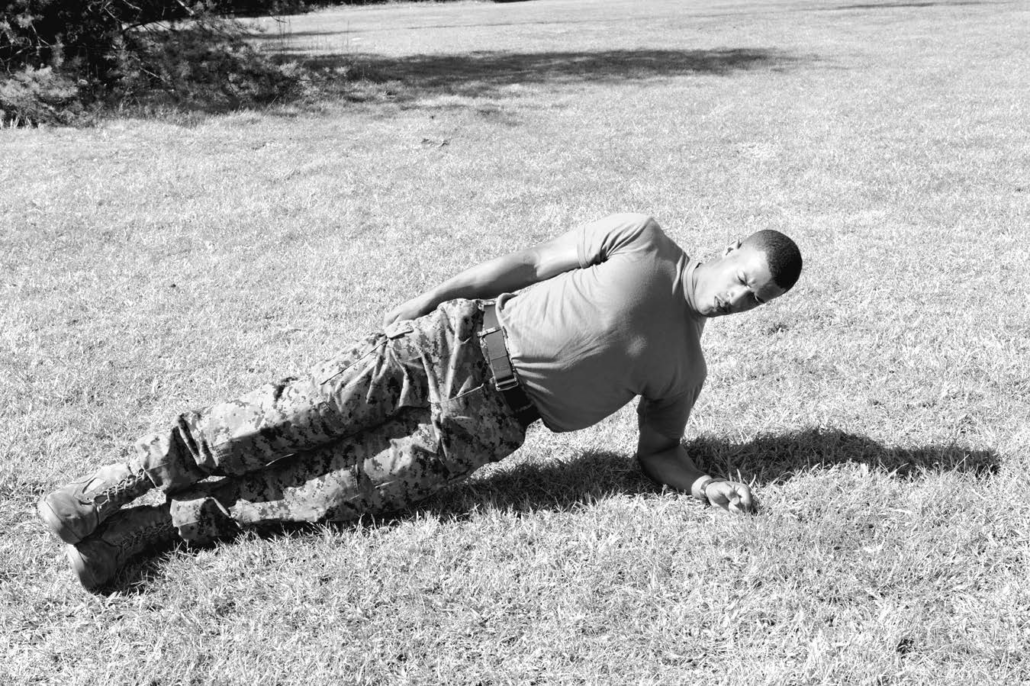

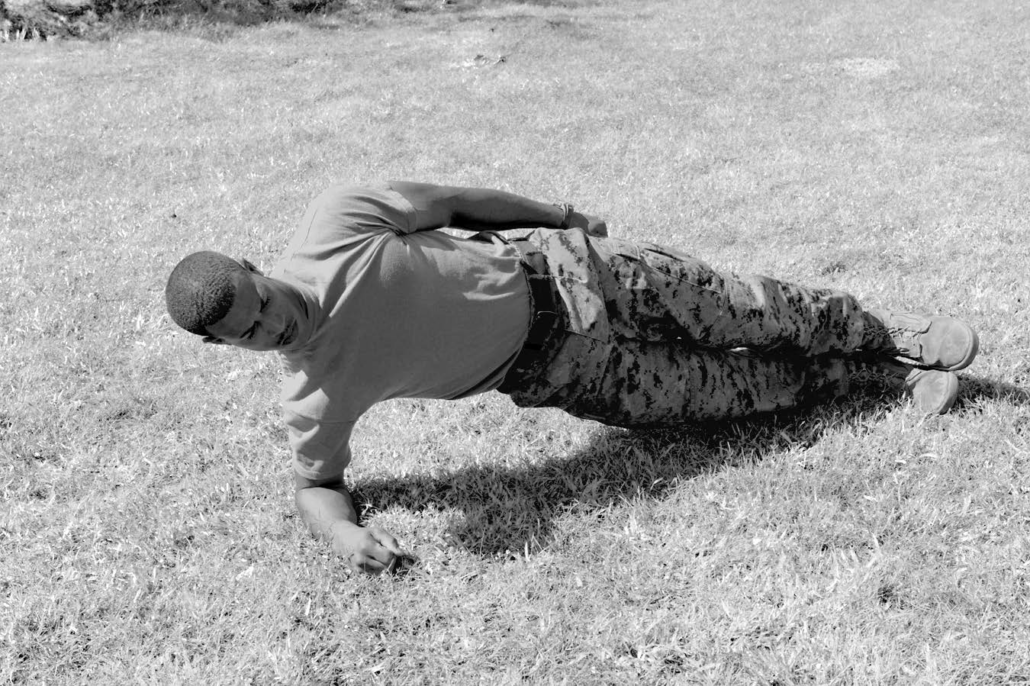

Side Planks. There are two positions of the side plank: left and right. This position may begin from the front plank or the front leaning rest position. The Marine will turn on one side while making only two points of contact with the deck: the forearm and foot. The upper arm will remain perpendicular with the ground. (See Figure 9-3.) The head will remain neutral while the hips will be up away from the deck, forward and in alignment with the shoulders. The shoulders will be rolled back and the position will resemble that of a modified position of attention. (See Figure 9-4.) The exercise will be held for a specified time.

Back Bridge. The Marine will begin in the front leaning rest or front plank. The Marine will shoot one arm underneath the opposite armpit and turn to his back. (See Figure 9-5) The hips will be raised while the Marine maintains three points of contact with the deck: each foot and the upper back. (See Figure 9-6) This exercise will be held for a specified time.

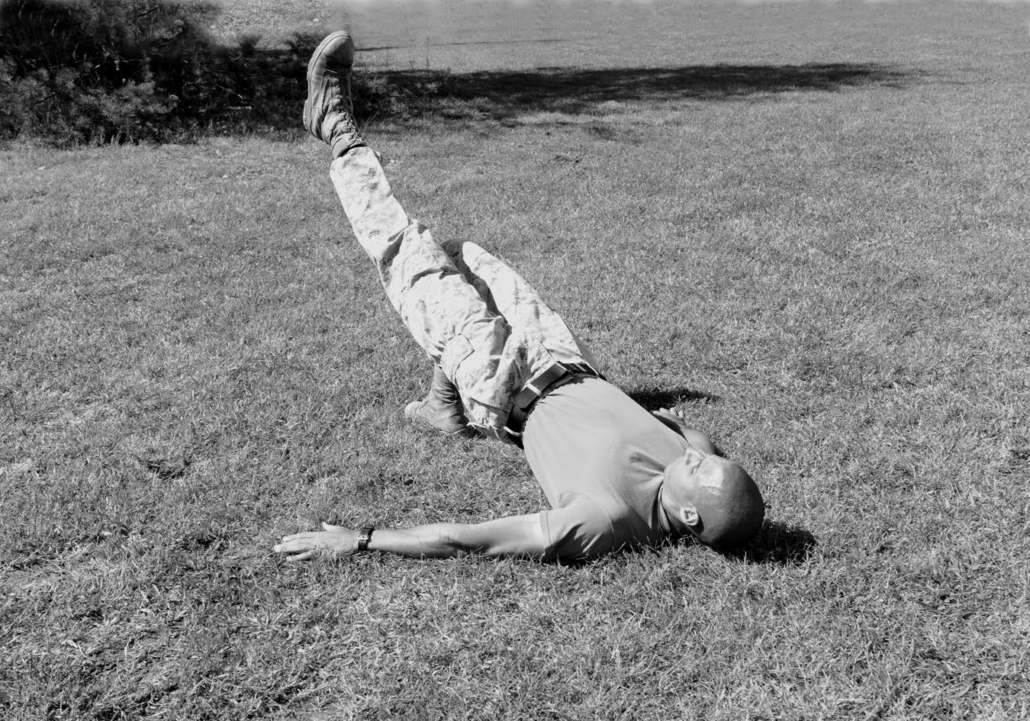

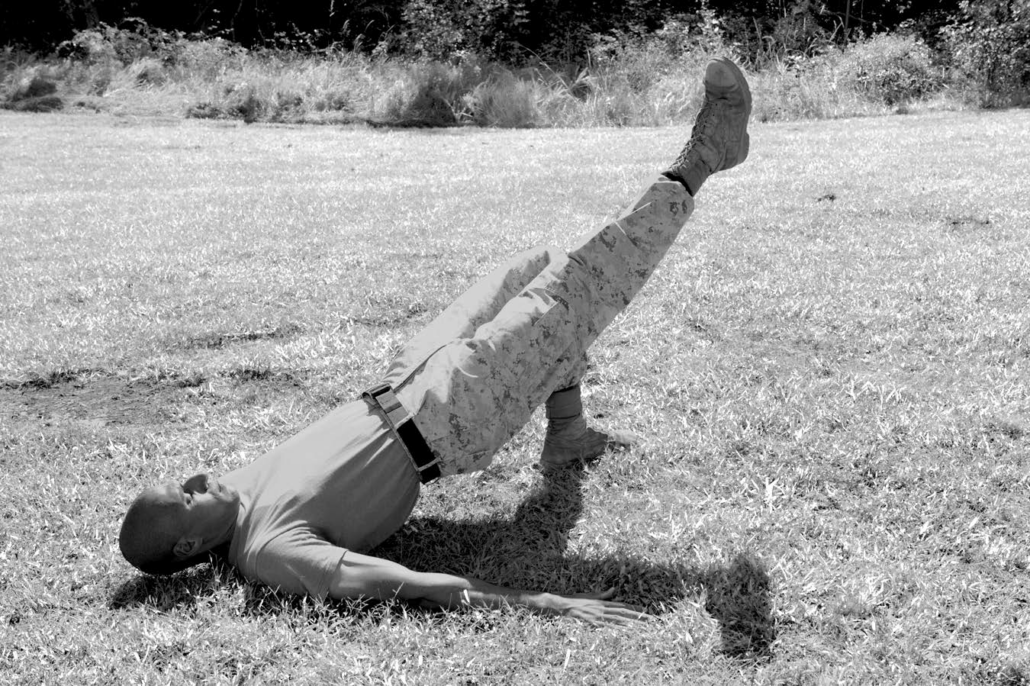

Back Bridge With Leg Extension. The Marine will begin in the back bridge position. The Marine will extend either leg to a 45-degree angle and point the toe upward. (See Figure 9-7) The Marine will continue to bridge the hips upward ensuring that the thighs are parallel but not touching. (See Figure 9-8.) Each leg should be held for a specified time.

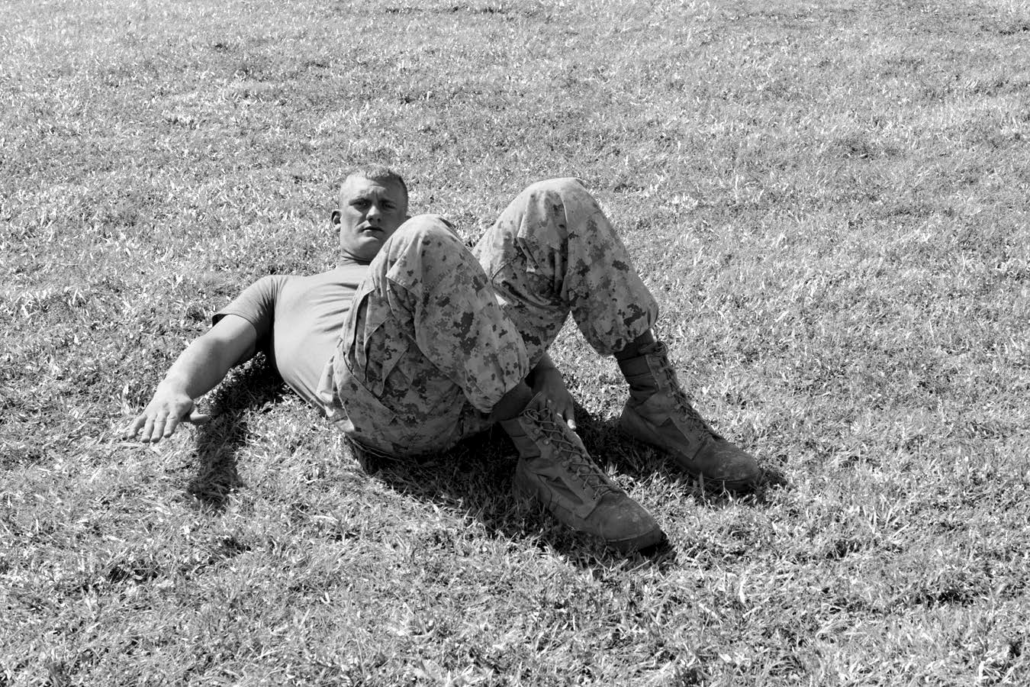

Abdominal Crunch. The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with hands behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. At no time during the exercise will the Marine pull up on the head. The knees will be bent and feet shall remain in contact with the deck at all times. (See Figure 9-9.) On order, the Marine will suck the stomach in and force the lower back into the deck. The Marine will use the abdominal muscles to raise the shoulders off the deck. (See Figure 9-10.) On order, the Marine will lower the torso back to the starting position.

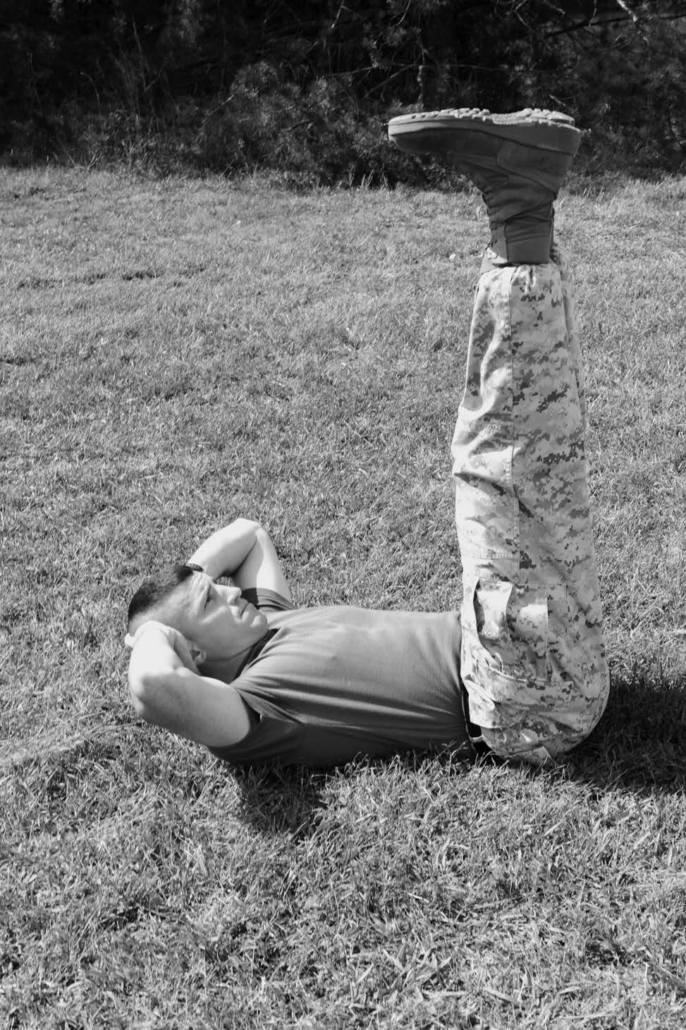

Combination Crunch. The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with hands behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. At no time during the exercise will the Marine pull up on the head. The thighs will be elevated and the knees bent at 90 degrees at all times. (See Figure 9-11.) On order, the Marine will suck the stomach in and force the lower back into the deck. The Marine will use the abdominal muscles to raise the shoulders and hips off the deck until neither the shoulder blades nor lower back are in contact with the deck. (See Figure 9-12.) On order, the Marine will lower the torso and hips to the starting position.

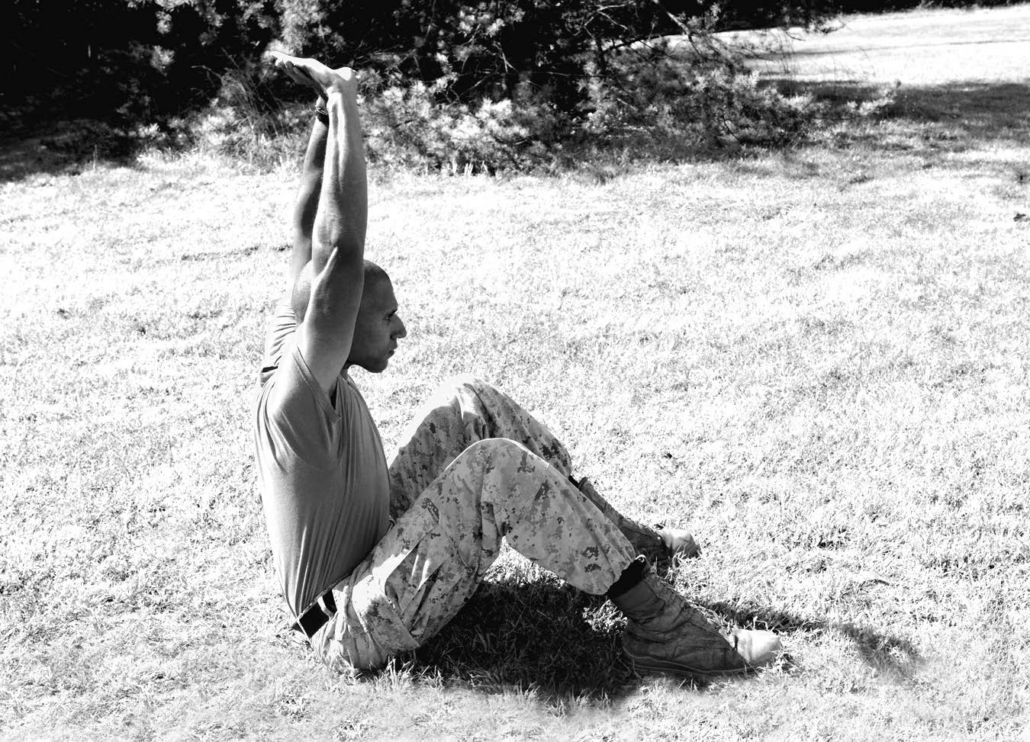

Free Foot Sit-Ups (Sit and Reach). The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with arms straight and extended perpendicular to the torso. The Marine will keep the knees bent and feet in contact with the deck at all times. (See Figure 9-13.) On order, the Marine will suck the stomach in and force the lower back into the deck. The Marine will use the abdominal muscles to raise the torso off the deck and into the seated position. The arms will remain perpendicular to the deck throughout the entire exercise. (See Figure 9-14.) On order, the Marine will lower the torso back to the starting position.

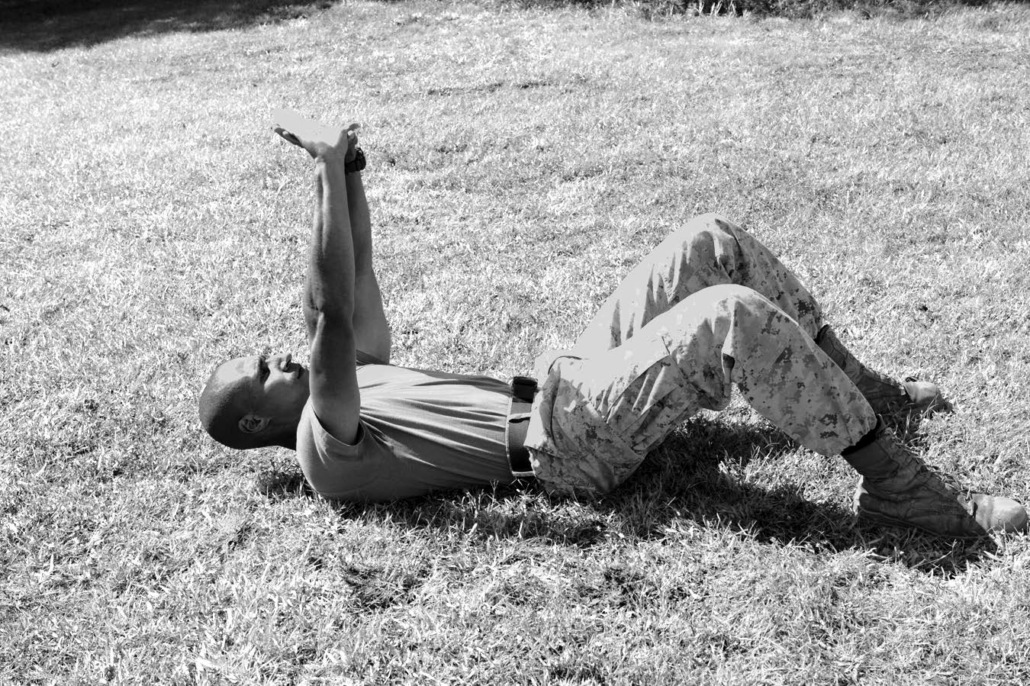

45- to 90-Degree Leg Raises. The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with hands behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard while the legs are straight and elevated at 90 degrees. (See Figure 9-15) The Marine will keep the legs elevated and straight at all times. On order, the Marine will suck the stomach in and force the lower back into the deck. The Marine will use the abdominal muscles to lower the legs to 45 degrees. (See Figure 9-16.) The lower back will be pressed to the deck throughout the entire exercise. On order, the Marine will use the abdominals to raise the legs back to the 90-degree angle.

Bicycle. The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with hands behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard while the legs are straight and elevated at approximately 45 degrees. At no time will the head be pulled during the exercise. The exercise will be executed to a four-count cadence. On the command one, the Marine will bring the left knee in toward the shoulders while raising the right elbow and shoulder blade off the deck toward the knee. (See Figure 9-17.) On two, the Marine will return to the starting position. On the command three, the Marine will bring the right knee in toward the shoulders while raising the left elbow and shoulder blade off the deck toward the knee. (See Figure 9-18.). On four, the Marine will return to the starting position.

Slide Side Reach. The Marine will begin by lying on the deck with hands off the deck and to the side of his body at a 45 degree angle. The Marine will keep the knees bent and feet in contact with the deck at all times. The exercise will be executed to a four-count cadence. On the command one, the Marine will crunch to the left side, forcing the left hand through the opening between the hamstring and calf. (See Figure 9-19.) On two, the Marine will return to the starting position. On the command three, the Marine will crunch to the right side, forcing the right hand through the opening between the hamstring and calf. (See Figure 9-20.) On four, the Marine will return to the starting position.

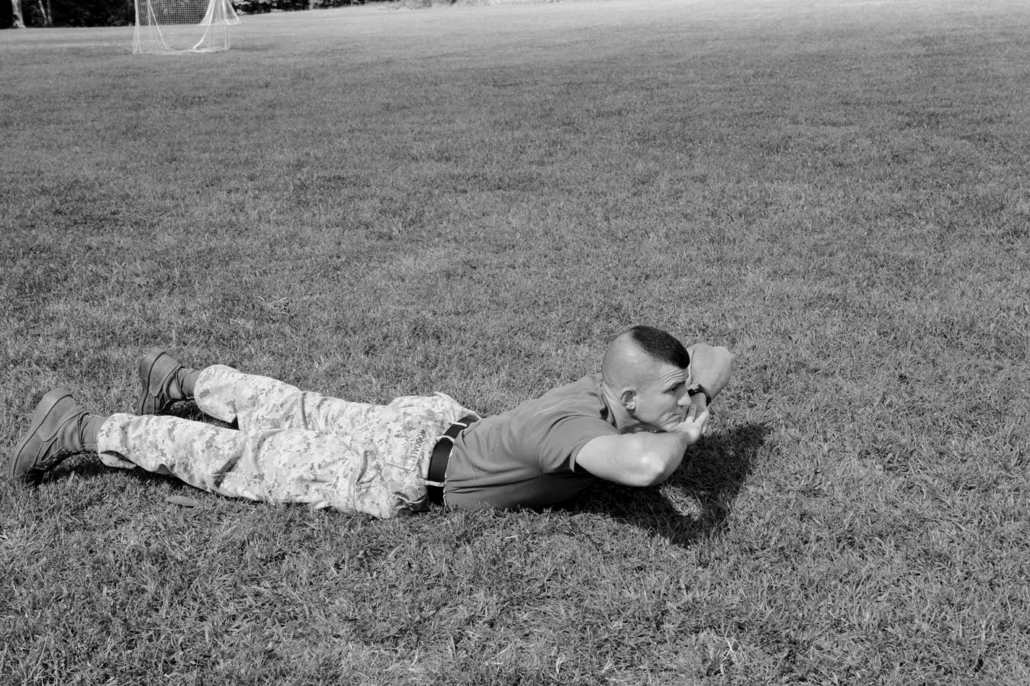

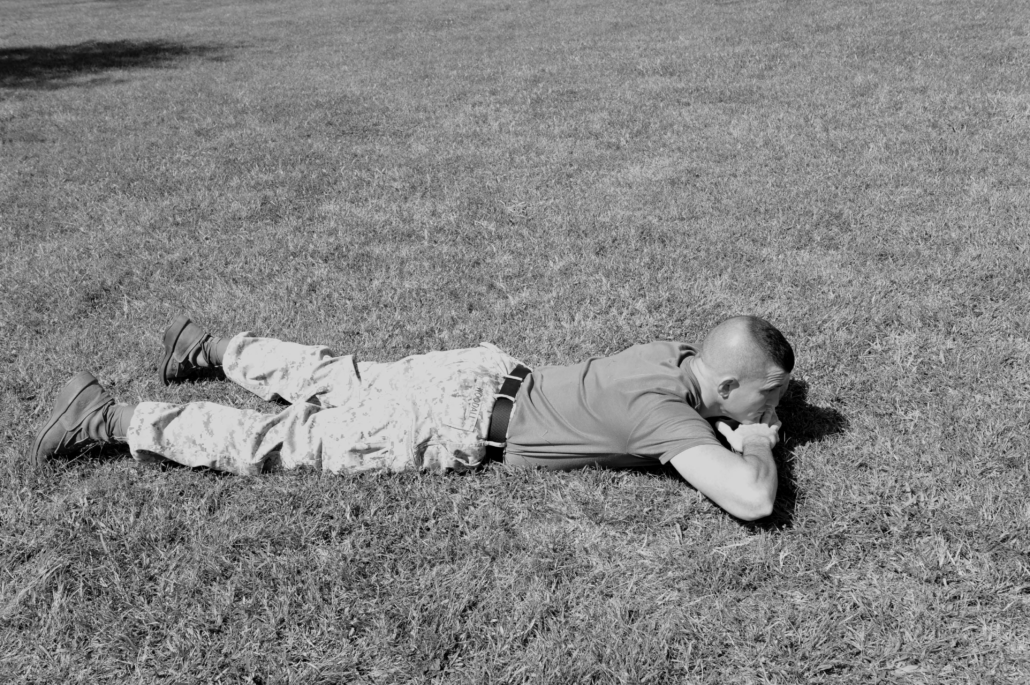

Hyperextensions. The Marine will begin by lying on the stomach in the beginner (arms to the side), intermediate (hands overlapped under the chin), or advanced (arms extended past the head and parallel to the deck) position. (See Figure 9-21). On order, the Marine will raise the torso while keeping the toes on the deck. (See Figure 9-22.) On order, the Marine will lower, not drop, the torso to the starting position.

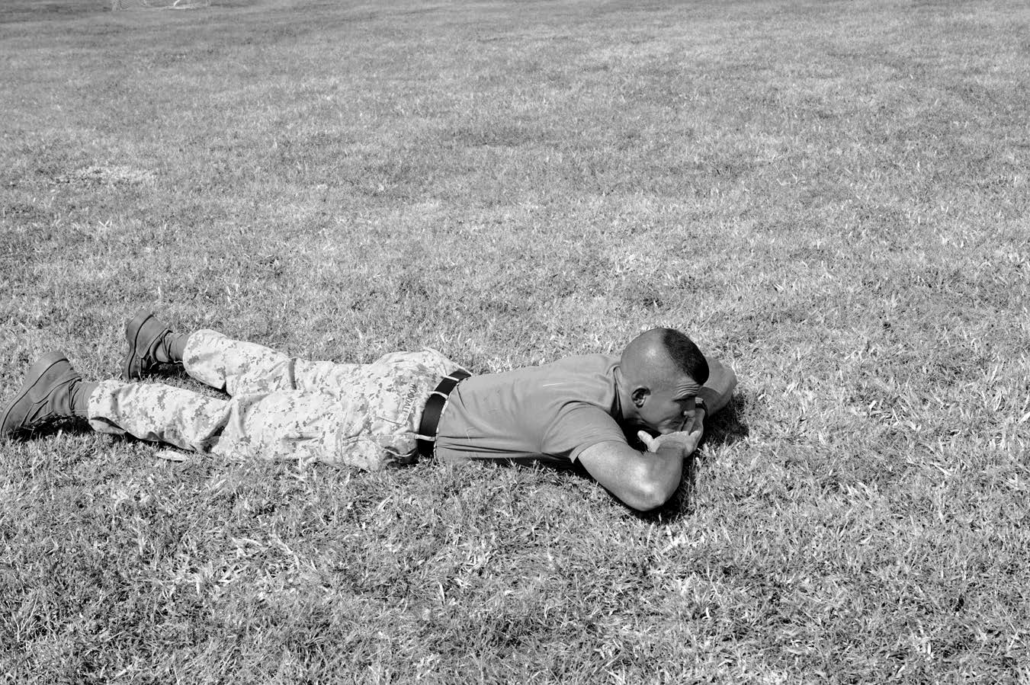

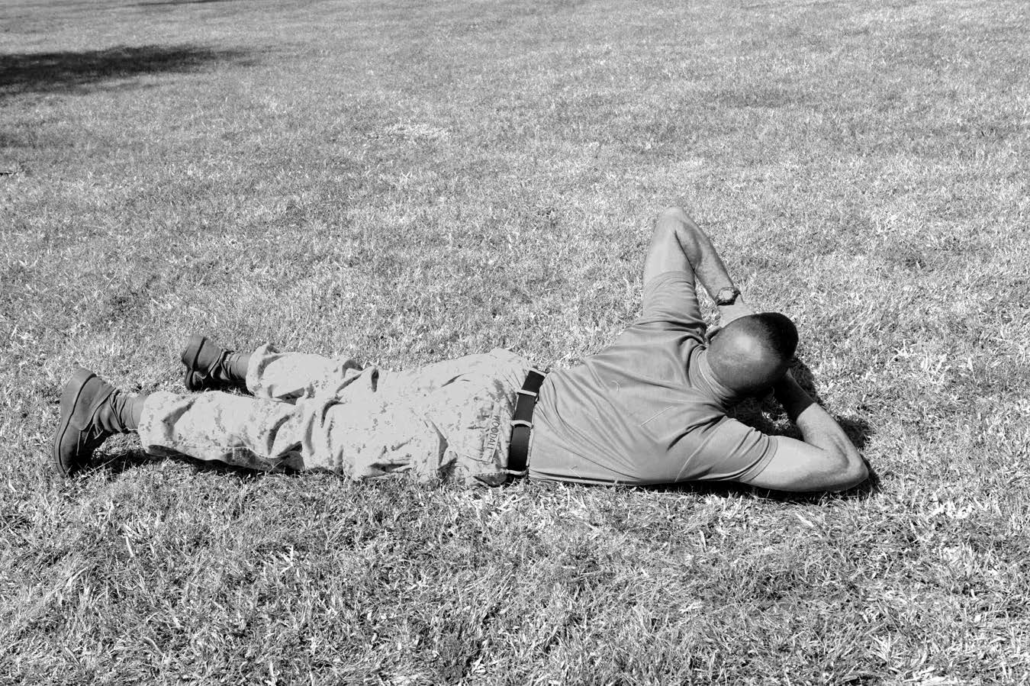

Reverse Hyperextensions. The Marine will begin by lying on the stomach with the hands overlapped and under the chin. (See Figure 9-23.) On order, the Marine will raise the feet and thighs off the deck while keeping the legs straight. (See Figure 9-24.) On the down command the Marine will lower, not drop, the legs to the deck.

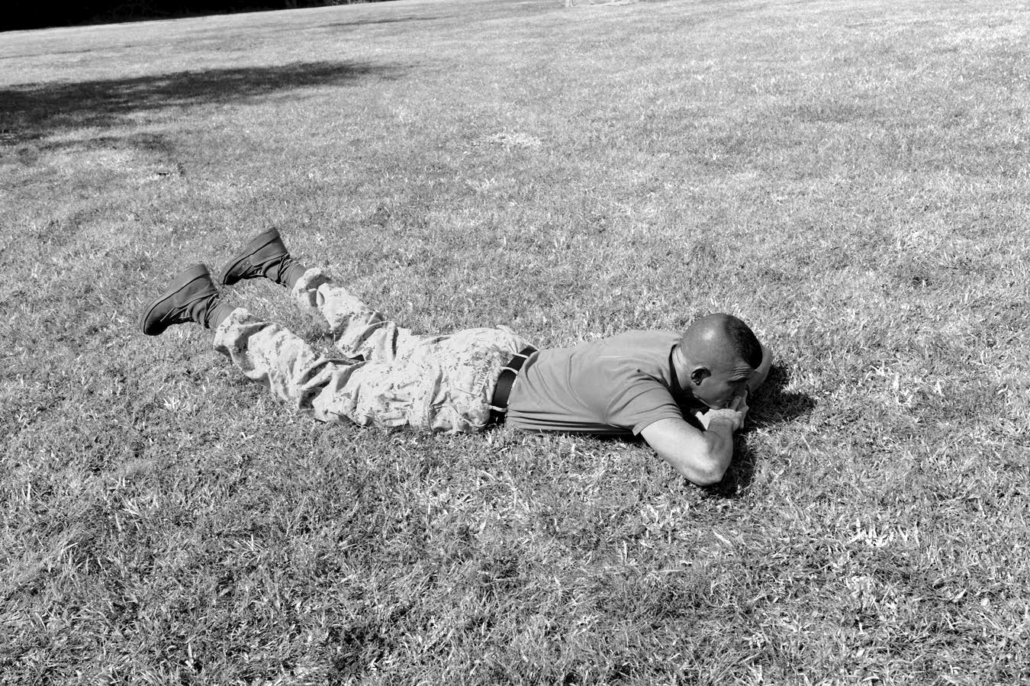

Combination Hyperextensions. The Marine will lie on his stomach in the beginner (arms to the side) intermediate (hands overlapped under the chin), or advanced (arms extended past the head and parallel to the deck) position. (See Figure 9-25.) On order, the Marine will raise the torso and thighs, while simultaneously lifting the legs straight and off the deck. (See Figure 9-26.) On order, the Marine will lower, not drop, the torso and thighs to the starting position.

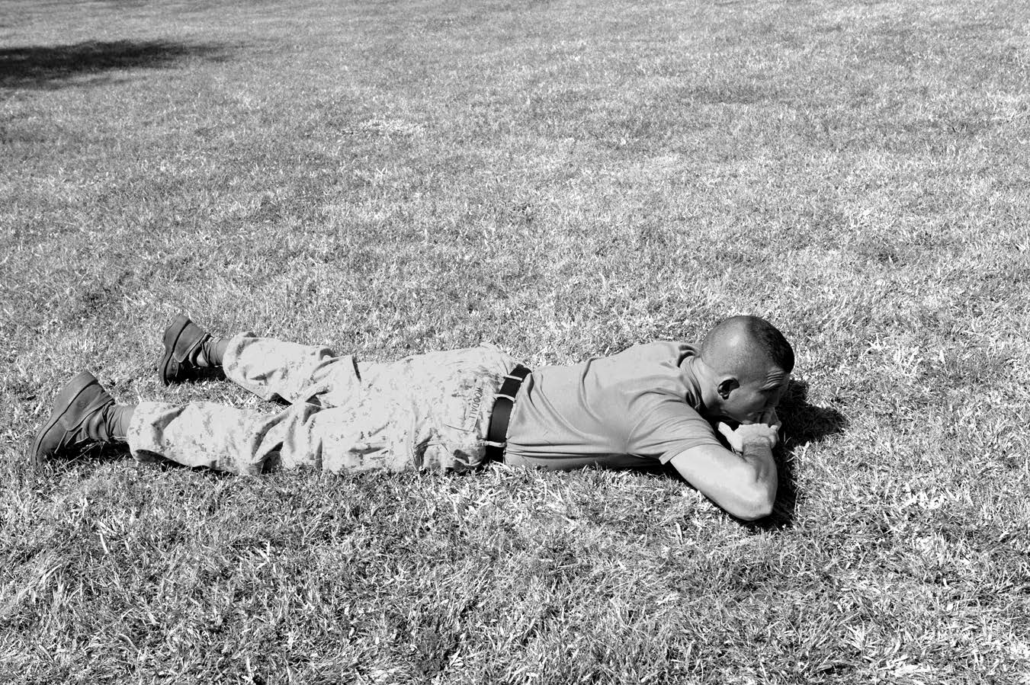

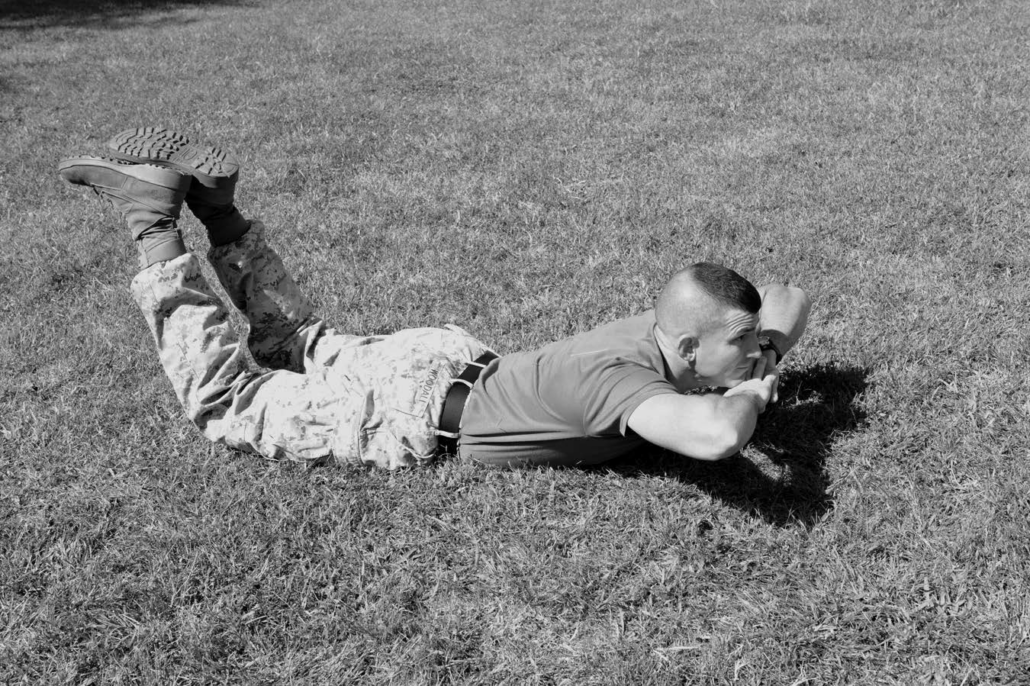

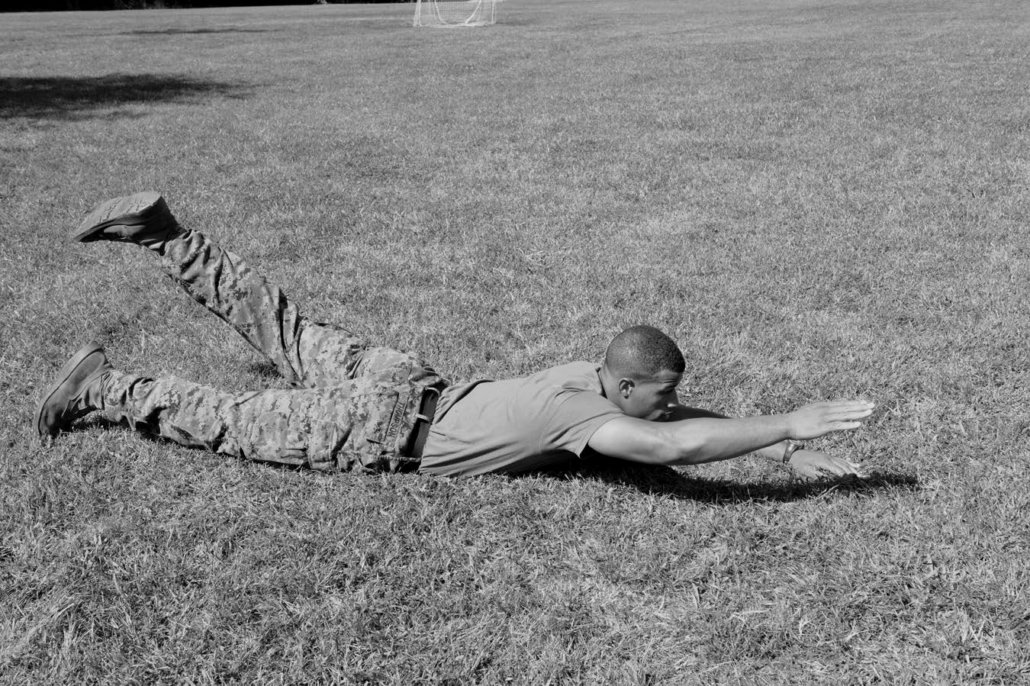

Swimmer Hyperextensions. The Marine will begin by lying on the stomach with the arms extended past the head and parallel to the deck. The exercise will be executed to a four-count cadence. On the command one, the Marine will raise his left arm and the right leg. (See Figure 9-27.) On two, the Marine will lower, not drop, the arm and leg to the starting position. On the command three, the Marine will raise the right arm and left leg. (See Figure 9-28.) On four, the Marine will lower, not drop, the arm and leg to the starting position.

Hyperextension Twist. The Marine will begin by lying on the stomach with the arms bent and hands overlapped under the chin. The exercise will be executed to a four-count cadence. On the command one, the Marine will raise the left elbow up and to the rear toward the right hip. (See Figures 9-29 and 9-30.) On two, the Marine will return to the starting position. On the command three, the Marine will raise the right elbow up and to the rear toward the left hip. On four, the Marine will return to the starting position. The feet will remain on the deck throughout the exercise.

Bodyweight Exercises

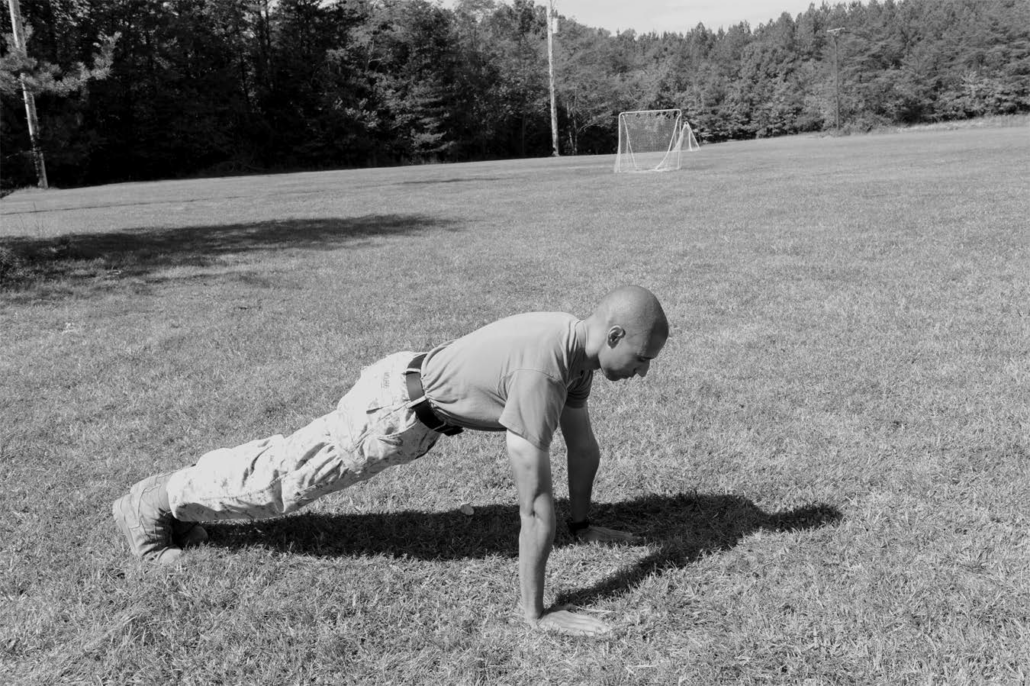

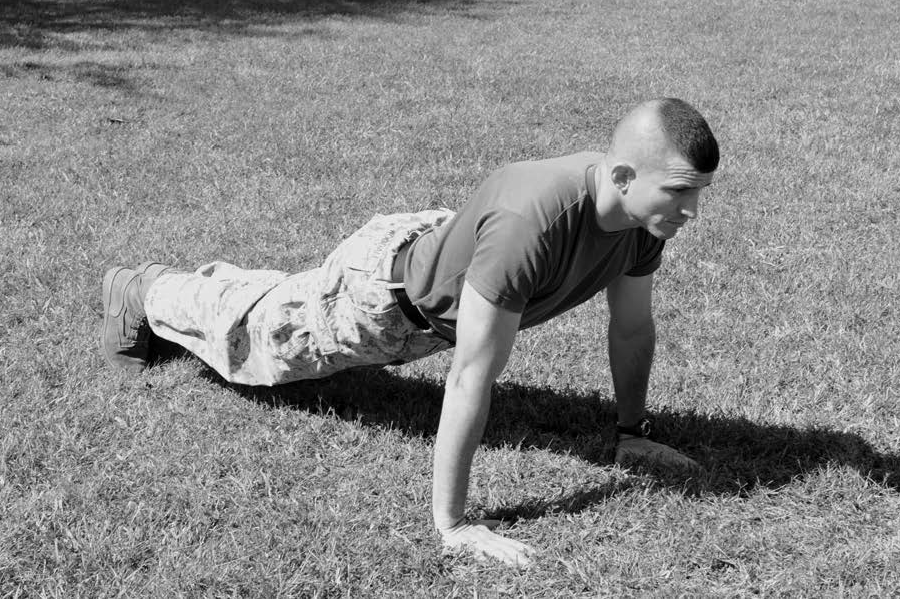

Push-Ups. The Marine will begin by lying on the stomach with the hands shoulder width apart. The “V” between the thumb and forefinger will be in line with the shoulder. The elbows will not point away from the torso more than 45 degrees. Throughout the entire exercise the Marine will keep the stomach sucked in and the back straight. The hips should be in line with the shoulders. (See Figure 9-31.) The exercise can be executed to the commands up and down or four-count cadence. On order, the Marine will press to the up position and hold. At this time the Marine will suck the stomach in and keep the back straight. The arms will be straight and elbows locked out; the hips will remain up and in alignment with the shoulders; the head will be in a neutral position. (See Figure 9-32.) On order, the Marine will lower the torso and lower body to the deck, maintaining the previously described alignment. To ensure proper form, the exercise should not be executed at a high tempo.

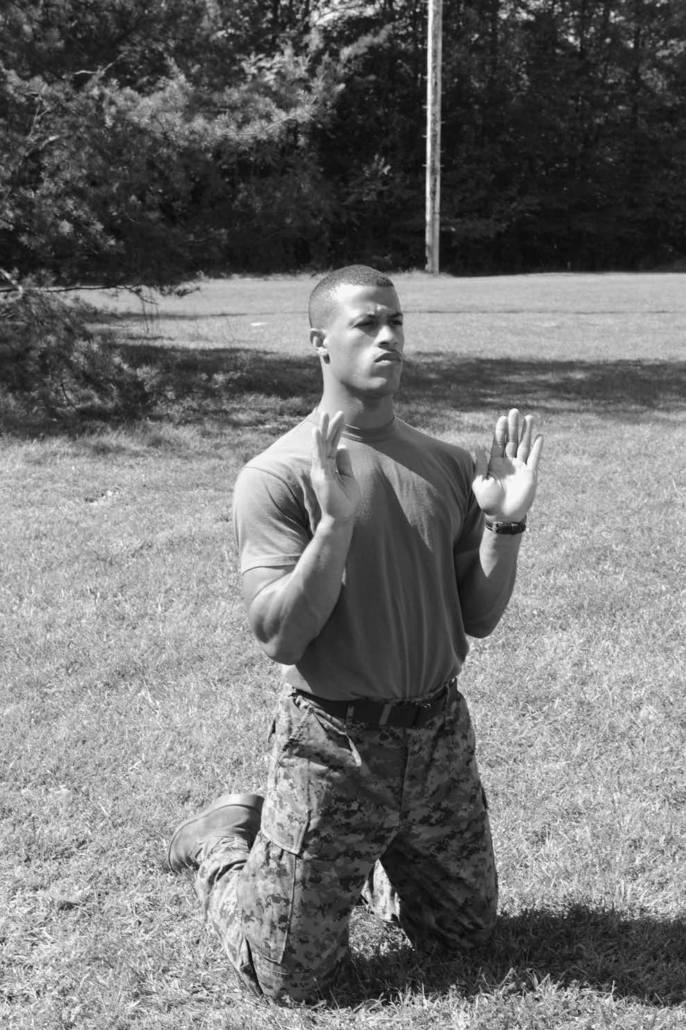

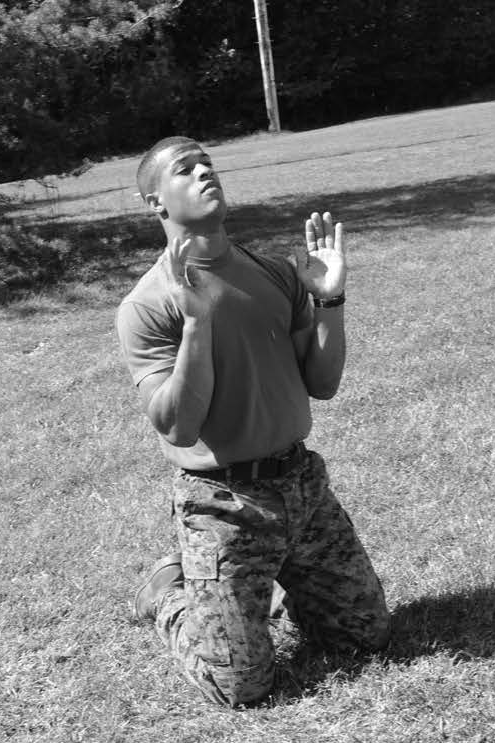

Power-Ups. The Marine will begin in the kneeling position with the stomach sucked in and the back straight. Forearms will be perpendicular with the deck; the hands will be placed approximately shoulder-width apart and the “V” between the thumb and forefinger will be slightly below and in line with the shoulder. (See Figure 9-33.) On order, the Marine will extend the arms and fall forward to the deck. The stomach will remain sucked in and the back flat throughout the entire exercise. Upon contact with the ground, the elbows will not point away from the torso more than 45 degrees. (See Figure 9-34.) On order, the Marine will rapidly extend the arms, explosively pushing away from the deck and returning to the kneeling position. (See Figure 9-35.) To ensure proper form, the exercise should not be executed at a high tempo.

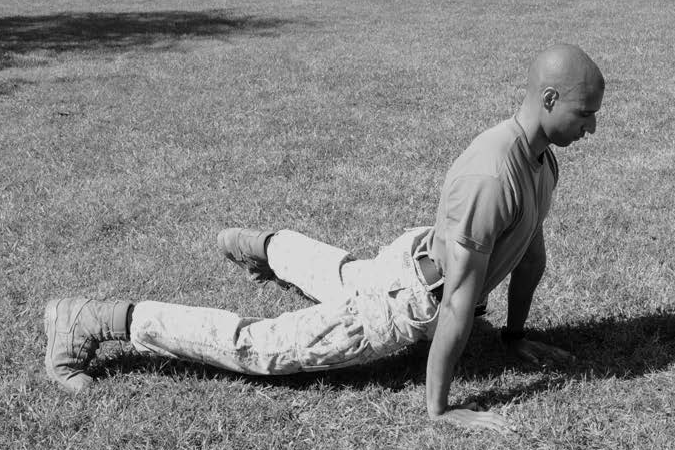

Dive Bombers. The Marine will begin in a modified push-up position with the hips raised higher than the chest and feet more than shoulder width apart. (See Figure 9-36.) On order, the Marine will lower the chest to the deck in a parabolic motion (see Figure 9-37) and extend upward until the arms are straight, the elbows locked out, and the chest is higher than the hips. (See Figure 9-38.) On order, the Marine will reverse the motion (see Figure 9-39) and return to the starting position (see Figure 9-40). The exercise should resemble the Marine attempting to push himself under a fence, or similar obstacle, and returning to the side from which he began.

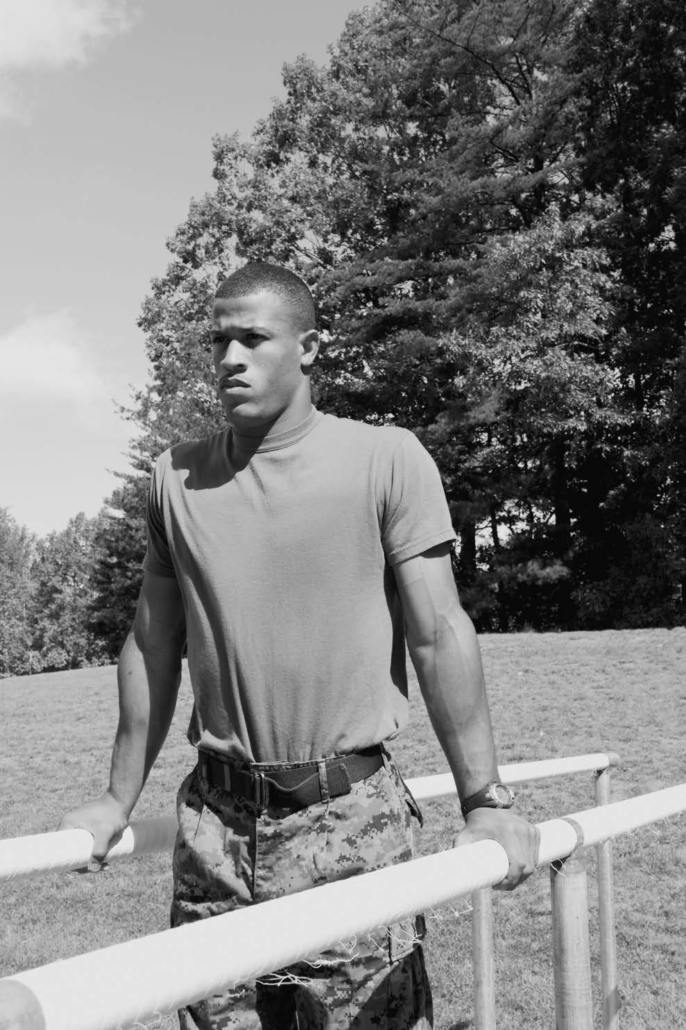

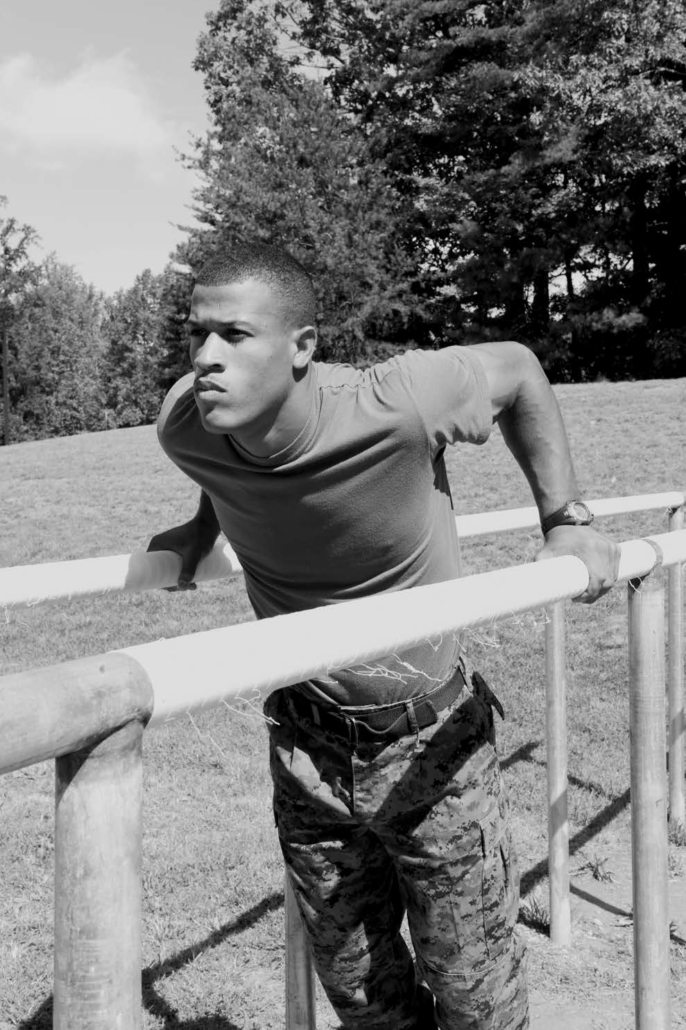

Dips. The Marine will perform this exercise on a dip bar or between two stable surfaces of approximately the same height. The Marine will begin with the arms fully extended and the elbows locked out. (See Figure 9-41.) On order, the Marine will slowly lower the body until the bend of the elbow is slightly less than 90 degrees or where the shoulders are lower than the elbows. (See Figure 9-42.) On order, the Marine will return to the starting position by extending the arms until the elbow has locked out. (See Figure 9-43.)

Burpees. The Marine will begin in a standing position. On order, the Marine will drop down into a squatting position, placing both hands flat on the deck approximately shoulder width apart. (See Figure 9-44.) The Marine will shoot both legs backwards (see Figure 9-45) and perform a push-up without resting on the deck (see Figure 9-46). While maintaining hand placement on the deck, the Marine will bring the legs back to the squatting position (see Figure 9-47) and perform a vertical leap for maximal height. This exercise most closely resembles an eight count bodybuilder executed at a much faster rate.

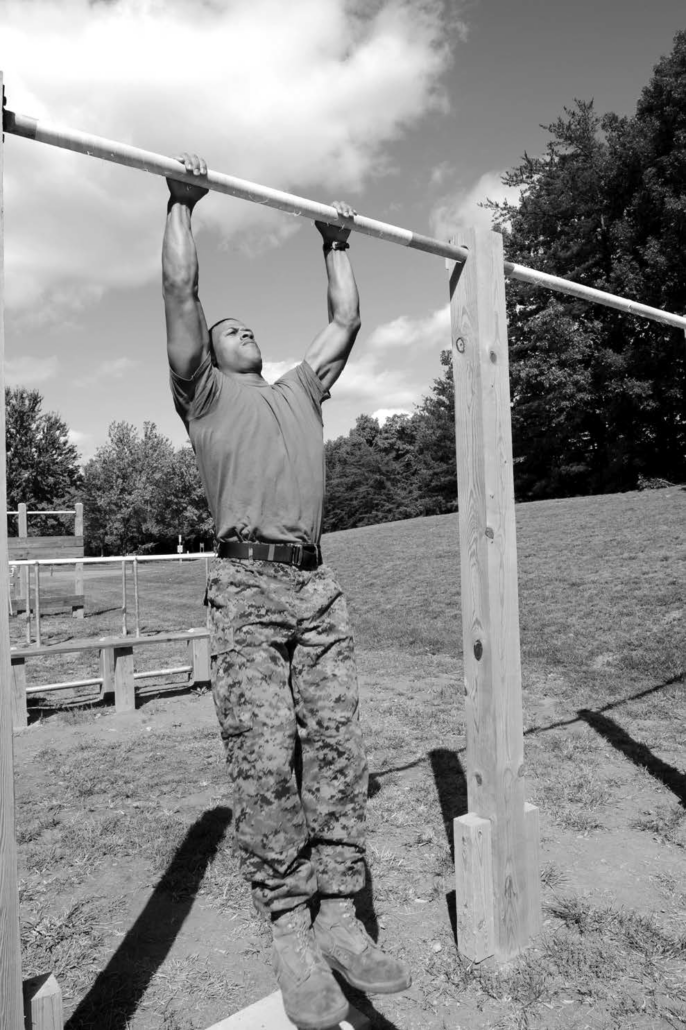

L Pull-Ups. The Marine will begin by mounting a pull-up bar and arriving at a “dead hang.” The Marine may grip the pull-up bar with the palms facing either outboard or inboard. The Marine will raise the lower body until the legs have formed a 90-degree angle with the torso, or the body forms an “L.” (See Figure 9-48.) On order, the Marine will execute a pull-up while maintaining the legs in the “L” position. (See Figure 9-49.) On order, the Marine will lower himself back to the starting position. (See Figure 9-50.)

Knees to Elbows. The Marine will begin by mounting a pull-up bar and arriving at a “dead hang.” The Marine may grip the pull-up bar with the palms facing either outboard or inboard. (See Figure 9-51.) On order, the Marine will raise the lower body until the knee caps and elbows are touching. (See Figure 9-52.) On order, the Marine will slowly lower the legs, returning to the starting position. (See Figure 9-53.)

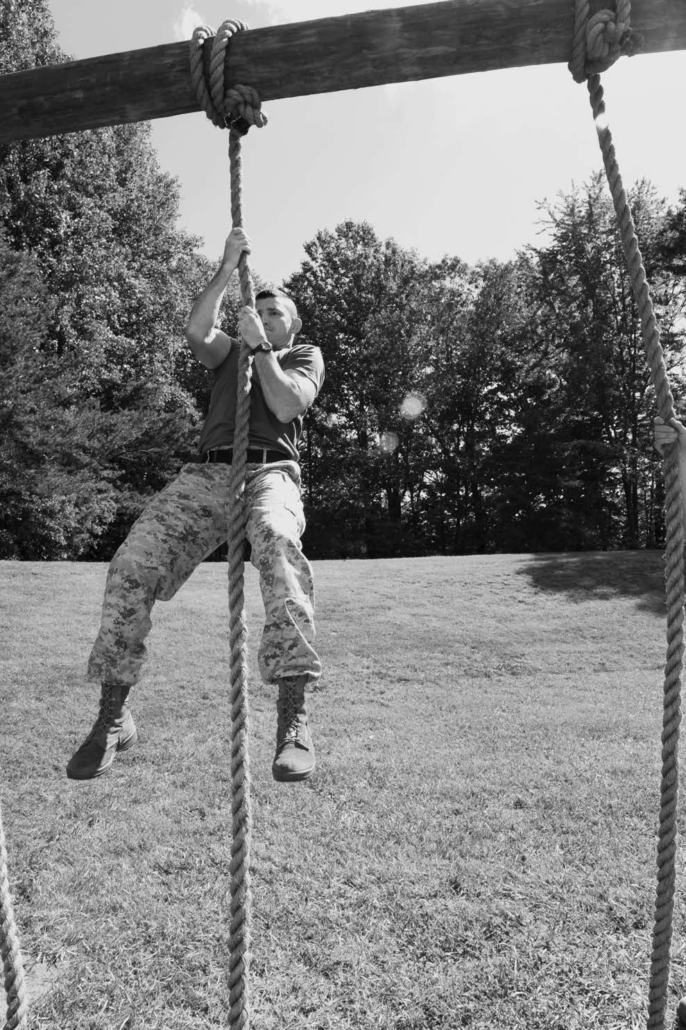

Rope Climb. The rope climb is a movement that all Marines should be able to perform. There are three primary means of climbing a rope; one involves mostly upper body strength, while the remaining two are significantly more energy efficient. The hand-over-hand method does not require the use of the legs or feet. (See Figure 9-54.) The “wrap” method involves the rope being wrapped around one leg and over the foot while simultaneously being locked into place by constant pressure exerted by the opposite foot. (See Figure 9-55.) The “J-hook” method involves the rope being threaded under one foot and overtop the opposite foot. (See Figure 9-56.)

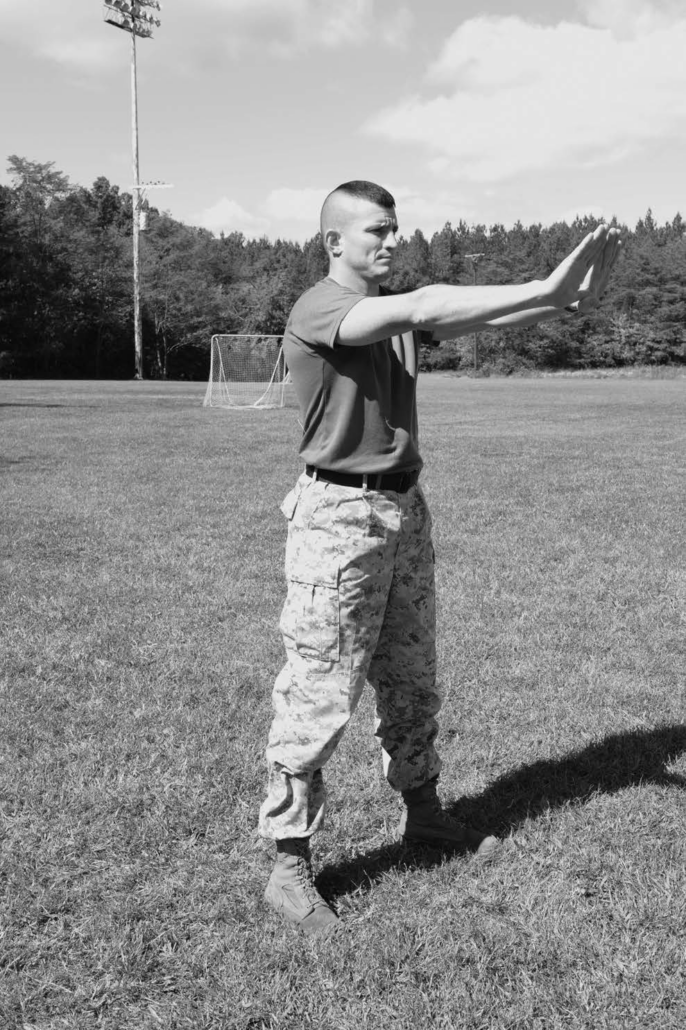

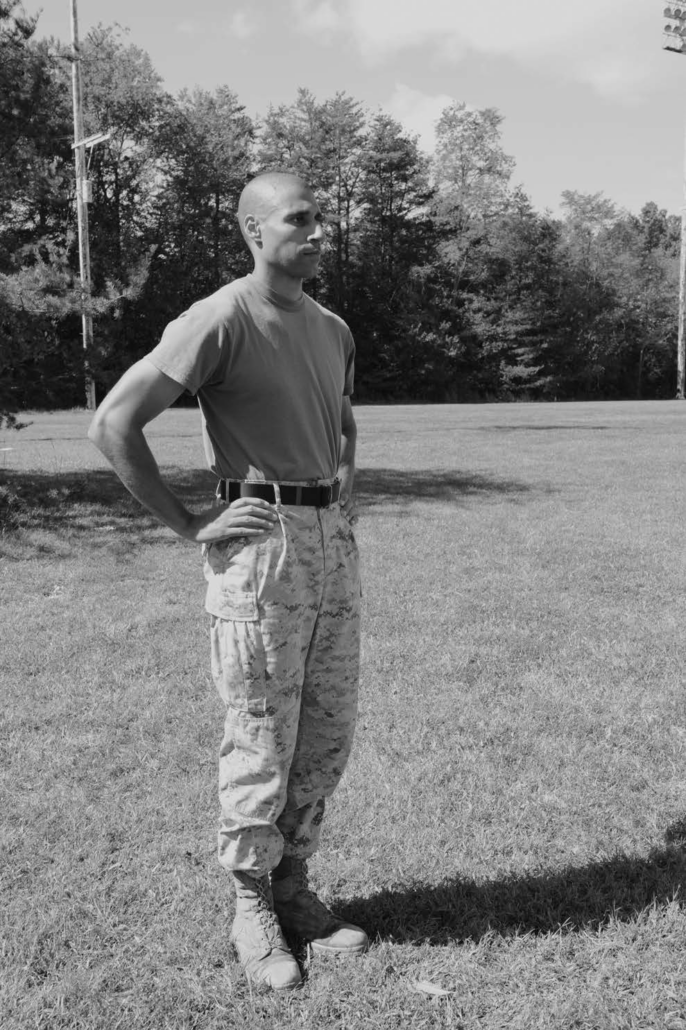

Body Squat. The Marine will begin in the standing position with the feet shoulder width apart. The stomach will be sucked in and the back flat. Hand placement may be behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. Alternatively, the arms may be held outstretched from the body, parallel with the deck. The head will be erect at all times. (See Figure 9-57.) On order, the Marine will bend at the knees, keeping the stomach sucked in and the back straight. The knees will not move forward past the toes. Although the optimal bend in the knee will result in slightly less than a 90-degree angle, individual flexibility will determine the Marine’s ability to perform a deep squat. The lumbar curve of the lower back will be maintained throughout the course of the exercise; weight will be distributed through the heels, while the chest and posterior are pushed out. (See Figure 9-58.) On order, the Marine will return to the starting position by extending the hips and straightening the legs. (See Figure 9-59.) To ensure proper form, the exercise should not be executed at a high tempo.

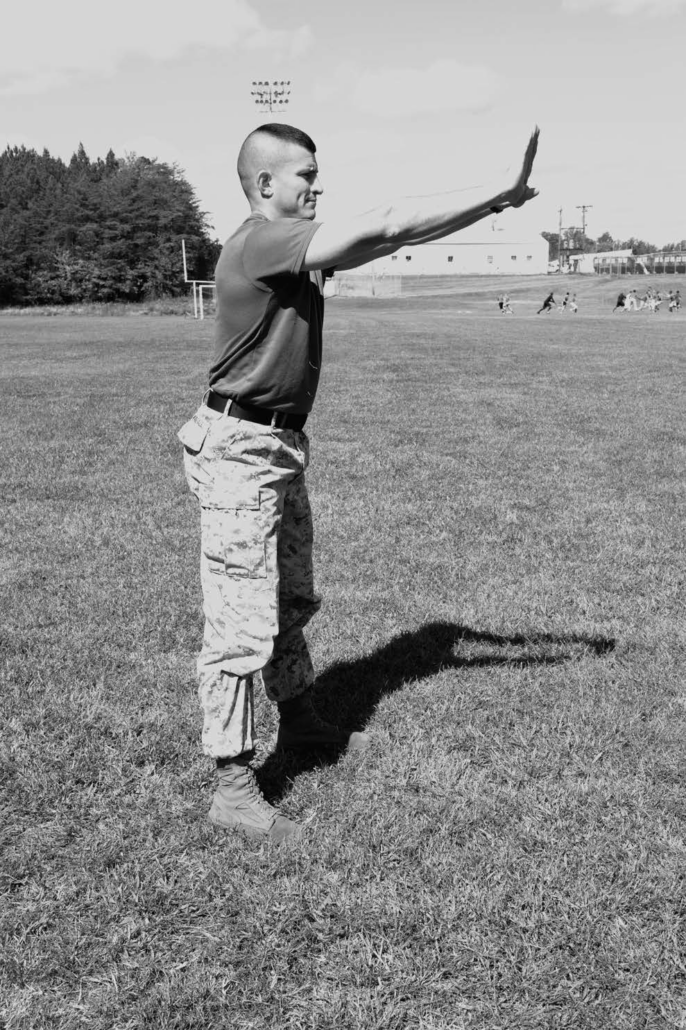

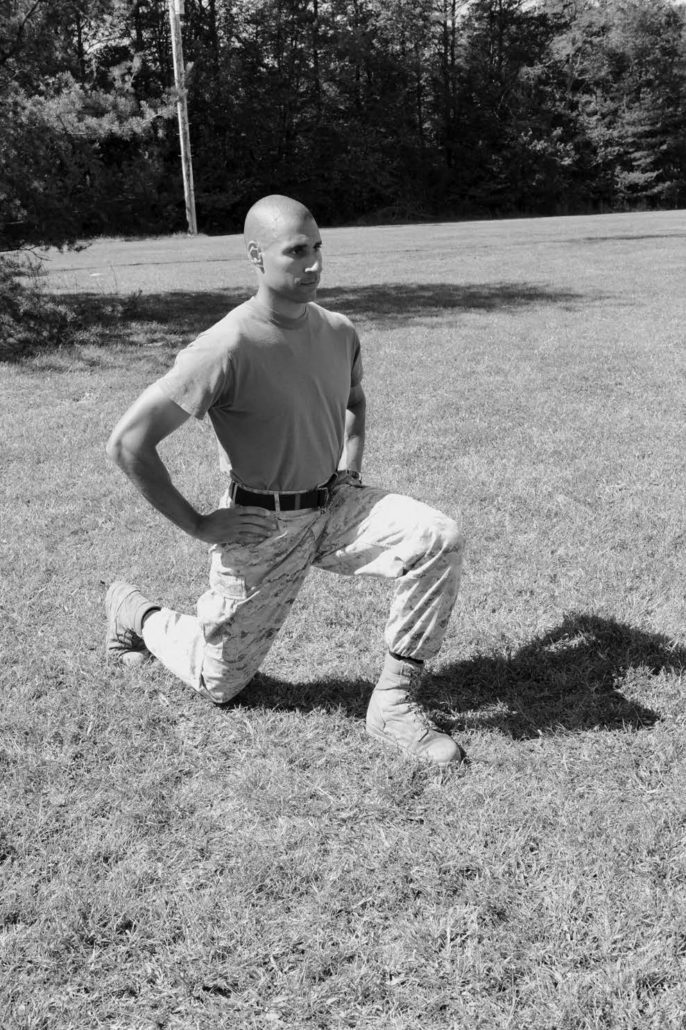

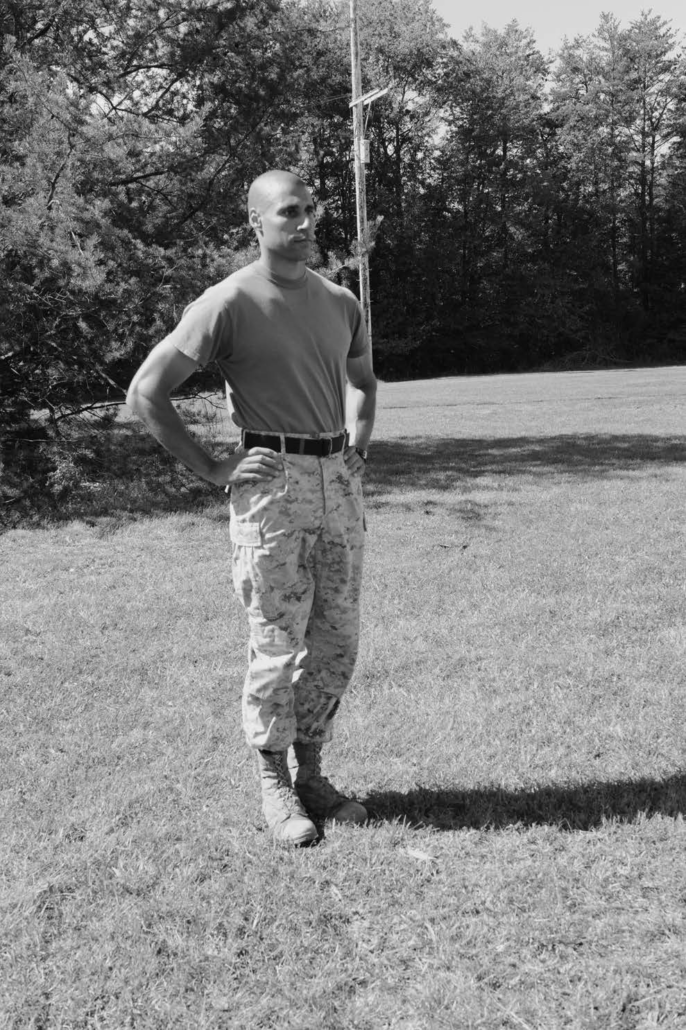

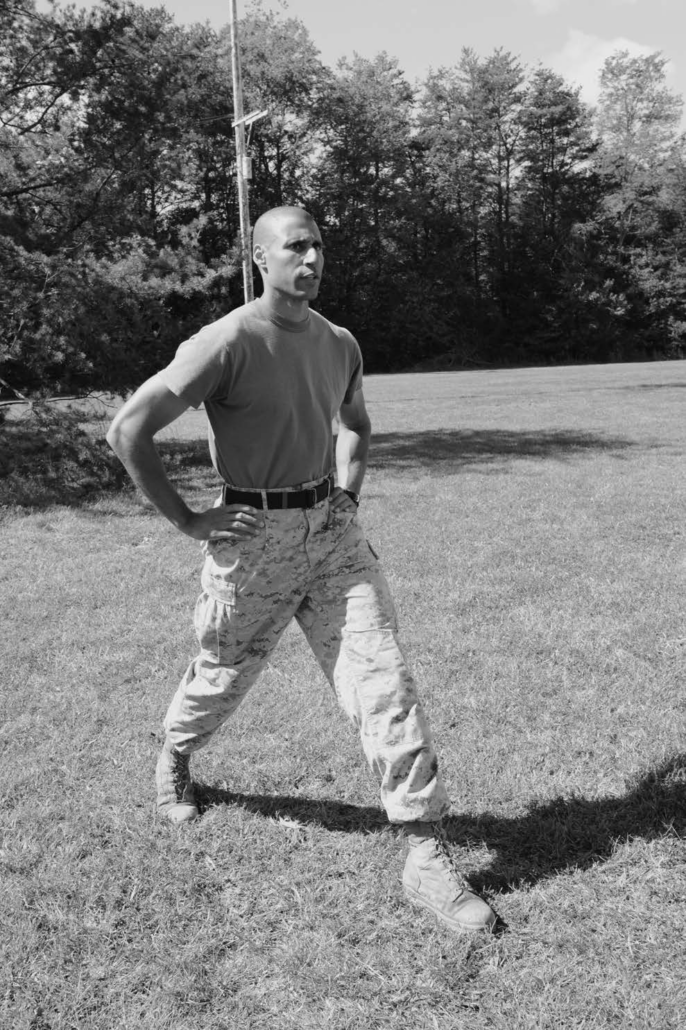

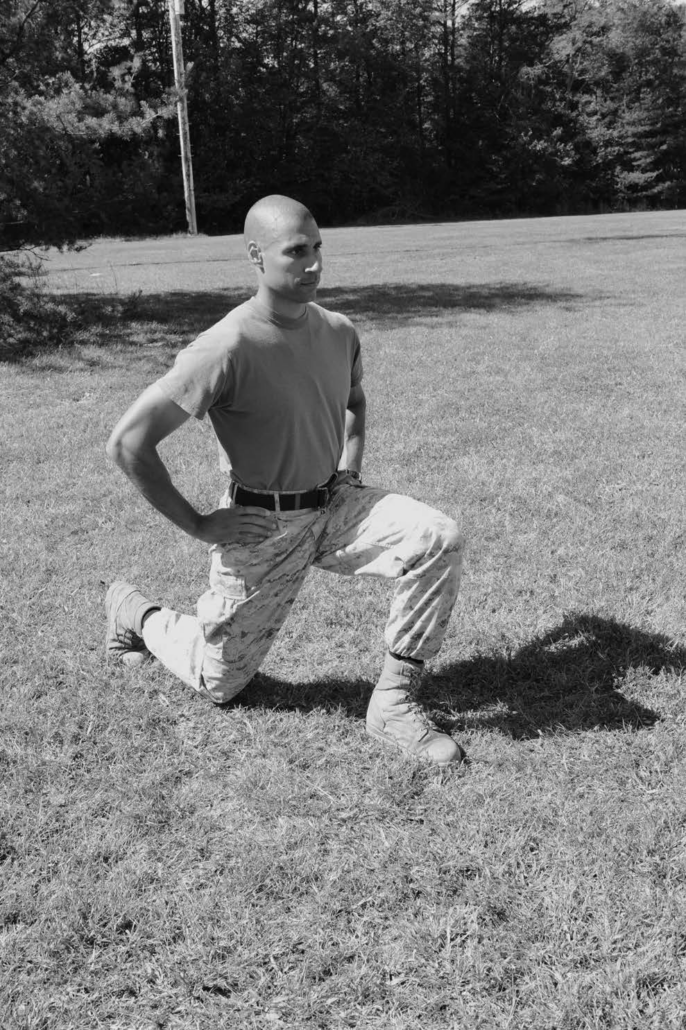

Lunges. The Marine will begin in the standing position with the feet shoulder width apart. The stomach will be sucked in and the back straight. Hand placement may be behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. Alternatively, the hands may be placed on the hips. The head will be erect at all times. (See Figure 9-60.) The exercise will be executed to a four-count cadence. On the command one, the Marine will step forward. The heel of the foot will make contact with the deck first, followed by the rest of the foot. The step should be wide enough to keep the knee from moving forward of the toes. The rear foot will provide balance during the exercise. On two, the Marine will lower the hips until the rear knee almost makes contact with the deck. Both the lead and rear legs will be bent to approximately 90 degrees. (See Figure 9-61.) On the command three, the Marine will rise up and begin to push off with the lead foot. The heel will be the last portion of the lead foot to break contact with the deck. On four, the Marine will have returned to the starting position. (See Figure 9-62.) The Marine will then alternate legs and repeat the exercise as prescribed above. To ensure proper form, the exercise should not be executed at a high tempo.

Split Squat. The Marine will begin the exercise with one leg forward. The stomach will be sucked in and the back straight. Hand placement may be behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. Alternatively, the hands may be placed on the hips. The head will be erect at all times. (See Figure 9-63.) This exercise may be executed to the commands down and up or as a four-count cadence. On order, the Marine will lower the hips straight down. The shoulders and hips will travel on the same imaginary line throughout the entire movement, as if the torso was affixed to a pole. The rear leg will be the working leg and the lead leg will provide the balance throughout the exercise. (See Figure 9-64.) On order, the Marine will rise up by extending the rear leg while keeping the stomach in and the back straight. The torso will continue to move as if it were affixed to a pole until the Marine returns to the starting position. (See Figure 9-65.) The Marine will continue the exercise until the assigned repetitions are accomplished before switching legs.

Buddy Exercises

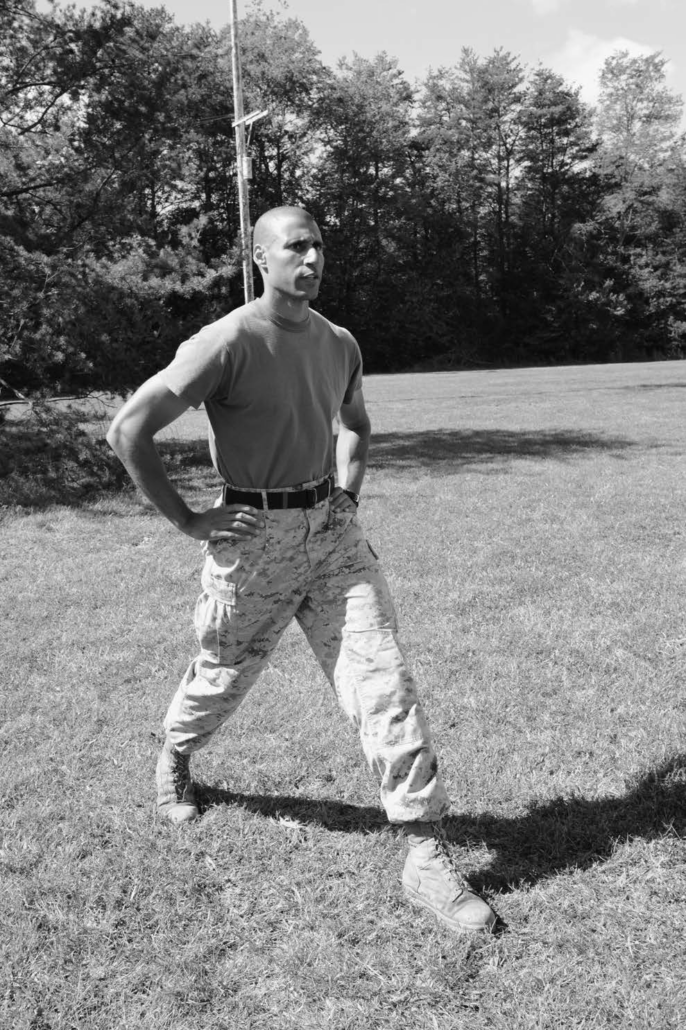

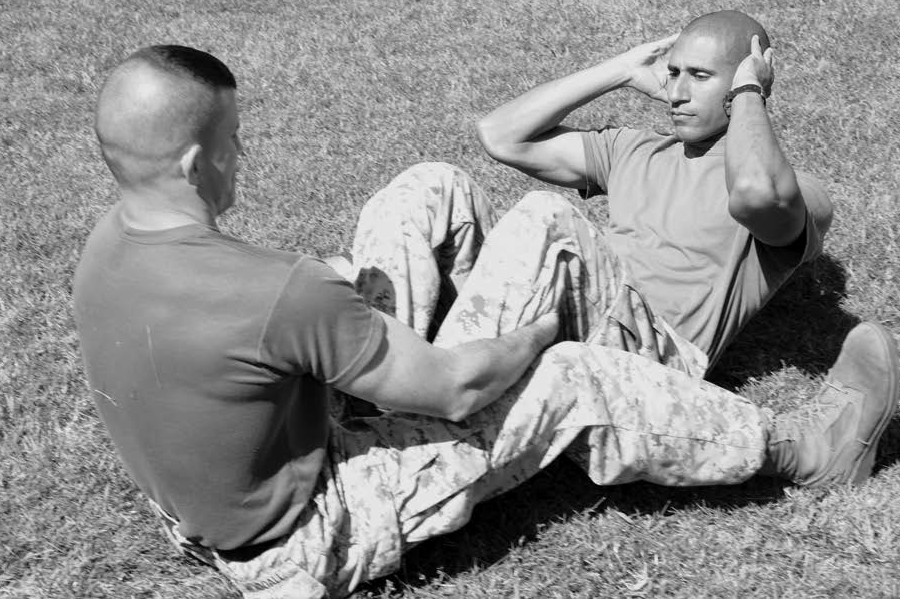

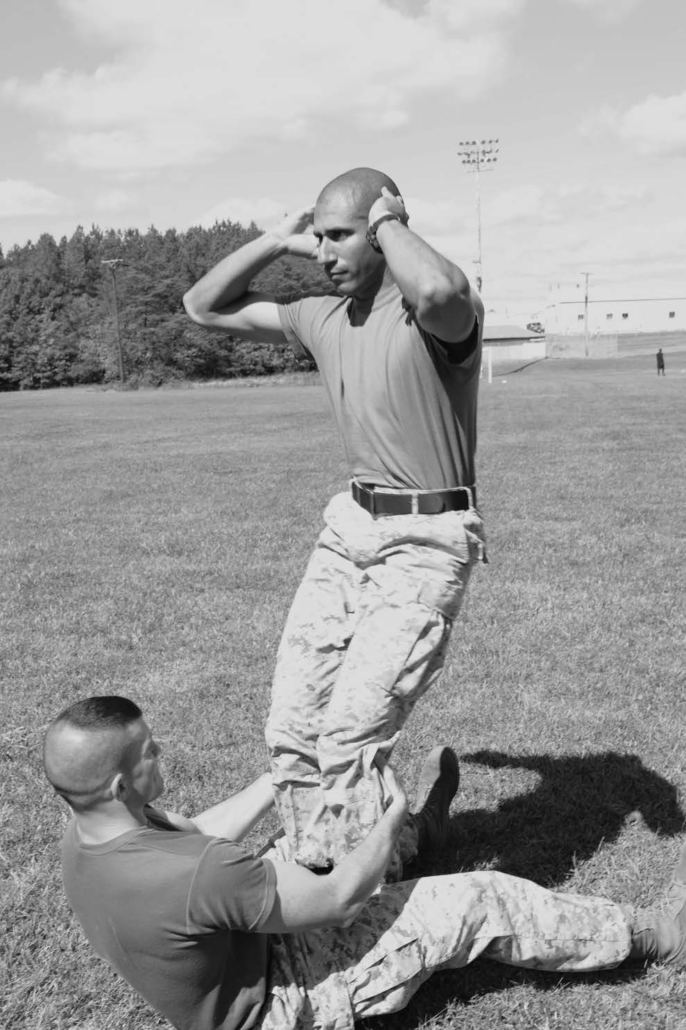

Vertical Sit-Ups. To begin, Marines will be seated with one Marine securing the other’s feet by grasping the left calf with the left hand and right calf with the right hand. (See Figure 9-66.) At no time during the exercise will the Marine securing the legs use the forearms to simultaneously secure the left and right calves. Additionally, placing the hands or forearms above the calves or directly behind the knee is not authorized. The Marine whose feet and legs are secured will be executing the exercise. The Marine executing the exercise will lay on the deck with arms crossed over the chest or the hands behind or to the side of the head. Fingers will not be interlocked and the elbows will remain pointing outboard. The Marine will have knees bent and the stomach sucked in. On order, the Marine will press the lower back into the deck executing a sit-up. (See Figure 9-67.) Once in the sit-up position, the Marine will transition to the standing position. (See Figure 9-68.) While standing, the Marine will push the hips forward while maintaining a straight back and erect head and shoulders. On order, the Marine will lower himself to the deck by first squatting down to the sit-up position and then lowering the torso back to the starting position. The Marine who is securing the feet and legs must maintain a secure hold throughout the exercise to provide balance and assistance.

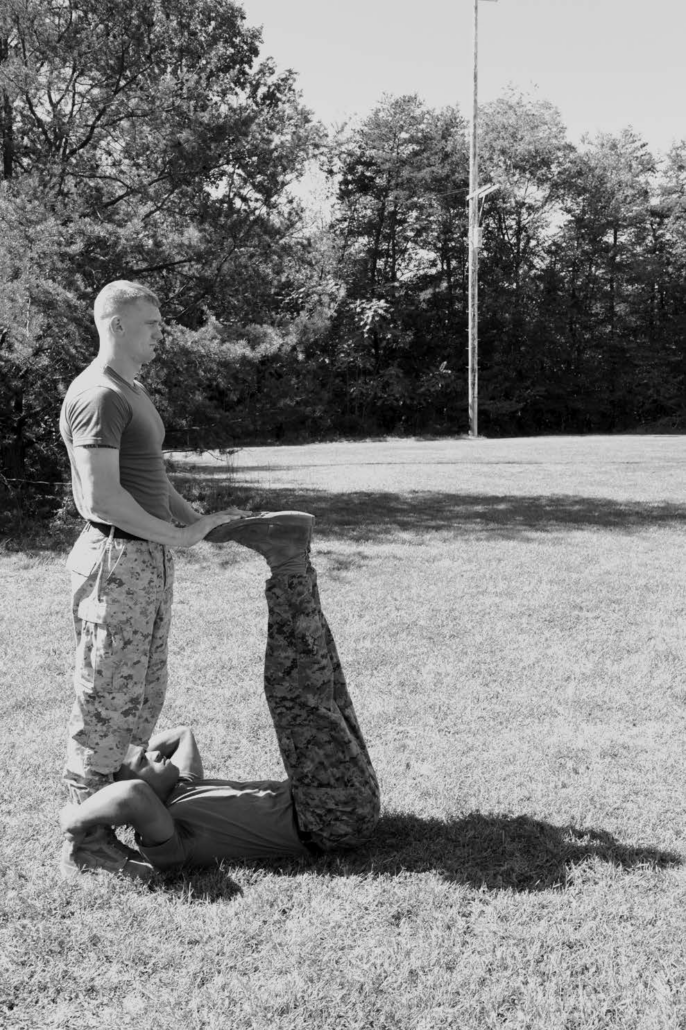

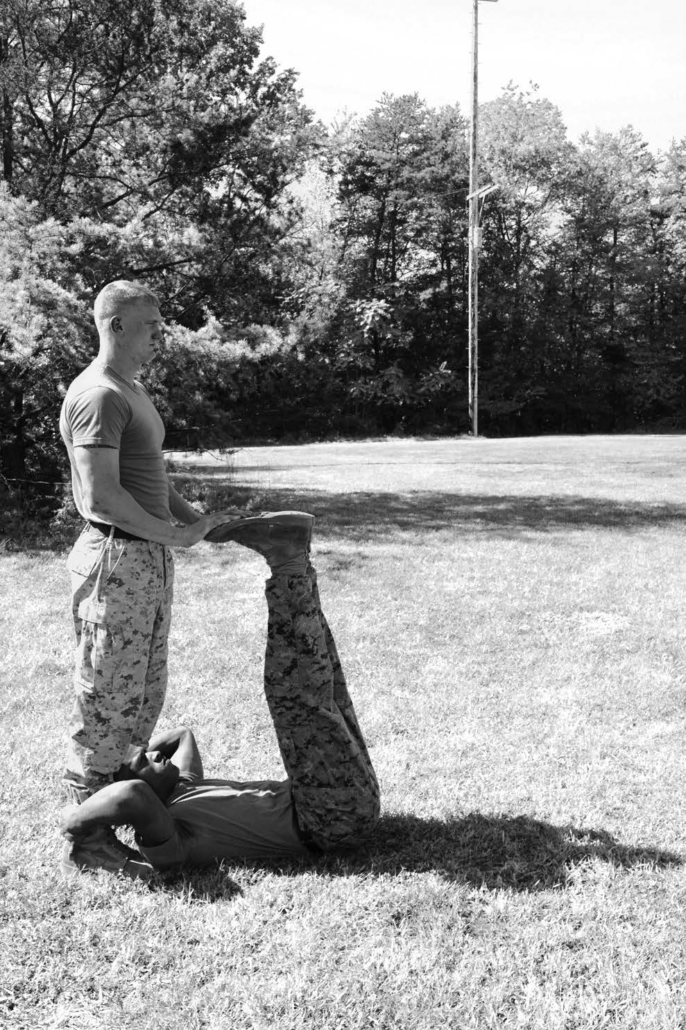

Buddy Leg Raises. To begin, one Marine will lay on the deck with the legs straight and perpendicular to the deck. The other Marine will straddle the head and grasp the feet of the Marine on the deck. The Marine standing will have the feet approximately shoulder width apart; the Marine on the deck will grasp the ankles of the Marine standing. (See Figure 9-69.) On order, the Marine standing will lightly push the legs toward the deck in the left, right, or center forward angles of movement. The Marine on the deck will keep the stomach sucked in and the lower back pressed into the deck. Once the Marines legs and feet are assisted downward, the Marine lying down will not allow them to touch the deck, but rather, will stop the legs and feet approximately six inches off the deck. (See Figure 9-70.) The Marine will then return the legs and feet to the starting position by contracting the abdominal muscles. (See Figure 9-71.) The Marine pushing the legs and feet toward the deck must be conscious of avoiding a predictable movement pattern. The Marine on the deck will be forced to work harder to stabilize the core if he is not cognizant of the direction in which the legs and feet are going to be pushed.

Squad Push-ups. Marines will begin by lying on their stomachs with their hands shoulder width apart. The “V” between the thumb and forefinger will be in line with the shoulder. The elbows will not point away from the torso more than 45 degrees. Throughout the entire exercise, Marines will keep their stomachs sucked in and backs flat. Each Marine will place the shins and feet on the shoulders of the Marine behind him. (See Figure 9-72.) On order, each Marine will push off the deck into a fully locked push-up position. At this time, Marines will suck their stomachs in and keep their backs straight. The arms will be straight and elbows locked out; the hips will remain up and in alignment with the shoulders; the head will be in a neutral position. (See Figure 9-73.) On order, all Marines will slowly lower themselves to the deck. (See Figure 9-74.) Anyone incapable of coming to a fully locked-out push-up position should be moved to the head or rear of the squad; Marines capable of performing such push-ups with relative ease should be moved to the center of the squad. It is recommended that no more than 10 Marines execute the exercise as a squad.

Buddy Squat. To begin, one Marine will begin in the fireman’s carry position with the feet shoulder width apart. The stomach will be sucked in and the back flat. The Marine being carried will use the free hand to support the lumbar curve of the other Marine’s lower back. (See Figure 9-75.) On order, the Marine will bend at the knees, keeping the stomach sucked in and the back flat. The knees will not move forward past the toes. Although the optimal bend in the knee will result in slightly less than a 90-degree angle, individual flexibility will determine the Marine’s ability to perform a deep squat. The lumbar curve of the lower back will be maintained throughout the course of the exercise; weight will be distributed through the heels, while the chest and posterior are pushed out. (See Figure 9-76.) On order, the Marine will return to the starting position by extending the hips and straightening the legs. (See Figure 9-77.) To ensure proper form, the exercise should not be executed at a high tempo.

Movement Exercises

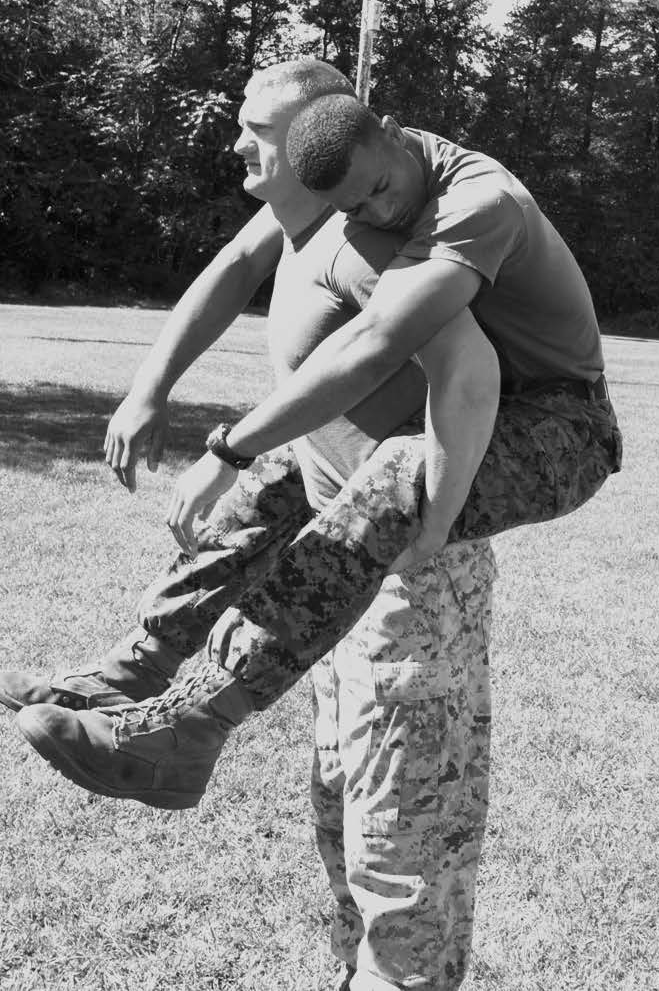

Fireman’s Carry. This movement exercise will begin with both Marines in the standing position. The Marine performing the carry will stand perpendicular to the Marine being carried. The Marine will execute a squat while reaching between the other Marine’s legs with one arm and grasping the other Marine’s wrist. The Marine being carried will lean forward until he lies across the other Marine’s shoulders. (See Figure 9-78.) The Marine performing the carry will transition control of the wrist to the hand that is between the legs of the Marine being carried. Once in this position, the Marine performing the carry will rise to the standing position. (See Figure 9-79.) Throughout the entire execution, the Marine being carried will place the palm of the free hand in the small of the back of the Marine performing the carry. On order, the Marine will rapidly carry the other Marine the designated distance. To prevent fatigue, Marines may change roles at the half-way point.

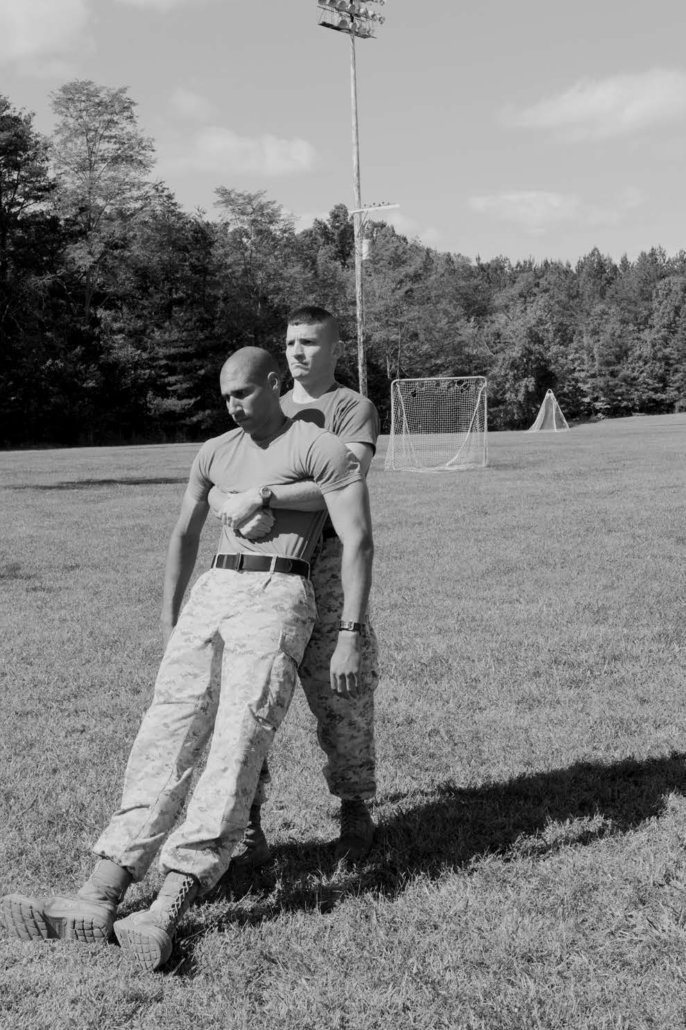

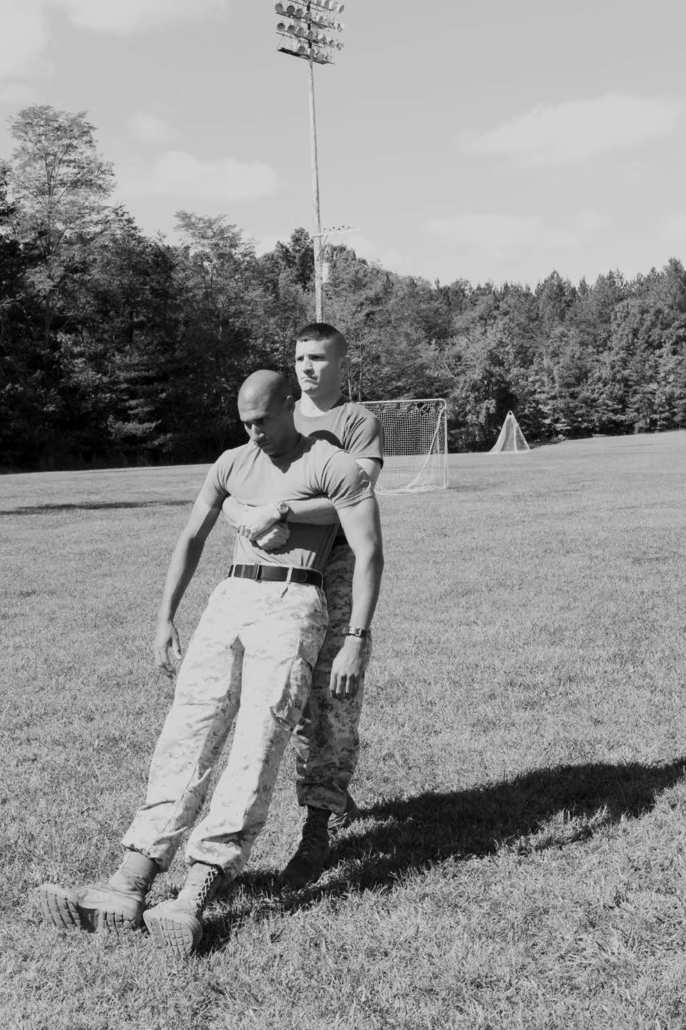

Under Arm Drag. This movement exercise will begin with Marines covered-down and facing the opposite direction of movement. The Marine standing behind the other Marine and closest to the starting line will execute the carry. The Marine performing the carry will thrust the forearms under the other Marine’s armpits, until the Marine’s back is touching the chest of the Marine performing the carry. The armpits should be positioned in the bend of the elbow or on the biceps of the Marine performing the carry. Once in this position, the Marine executing the drag will lock the hands without interlocking the fingers. (See Figure 9-80.) On order, the Marine will begin to move backwards in the direction of movement. The Marine that is being dragged will begin to move closer to the deck. The Marine executing the drag must lower his hips in order to remain upright throughout the carry. (See Figure 9-81.) The feet of the Marine being carried will be splayed such that the instep of the foot is facing upward. At no time will the Marine being carried dig the heels into the deck or place the soles of the feet on the deck. Additionally, at no time will the Marine being carried assist the Marine executing the drag. To prevent fatigue, shorter distances (25 meters or less) are preferred and Marines may change roles at the halfway point.

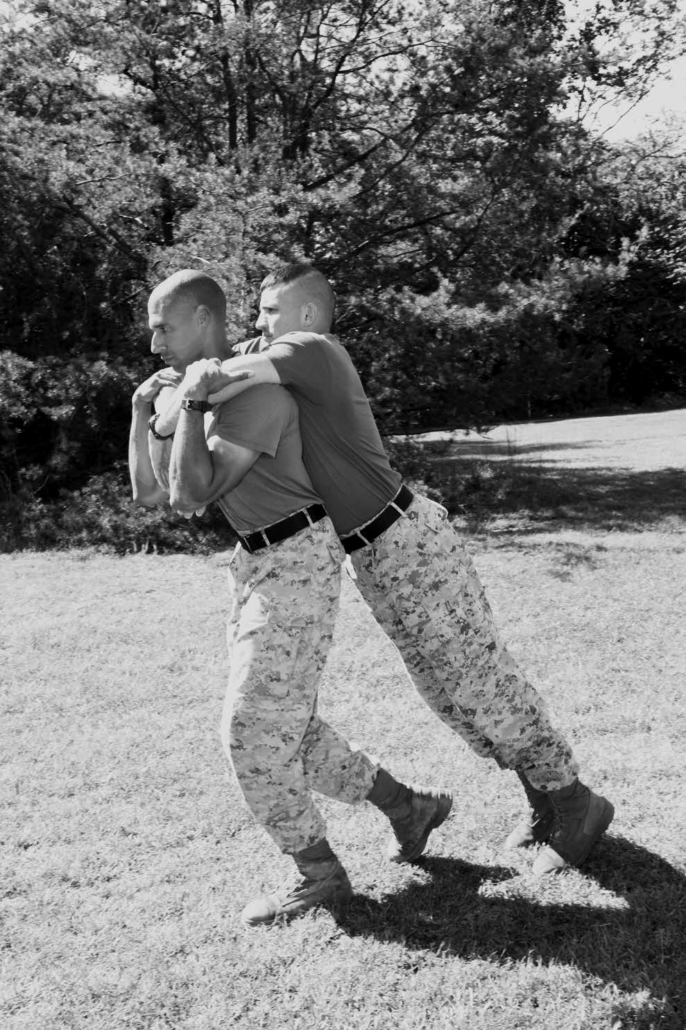

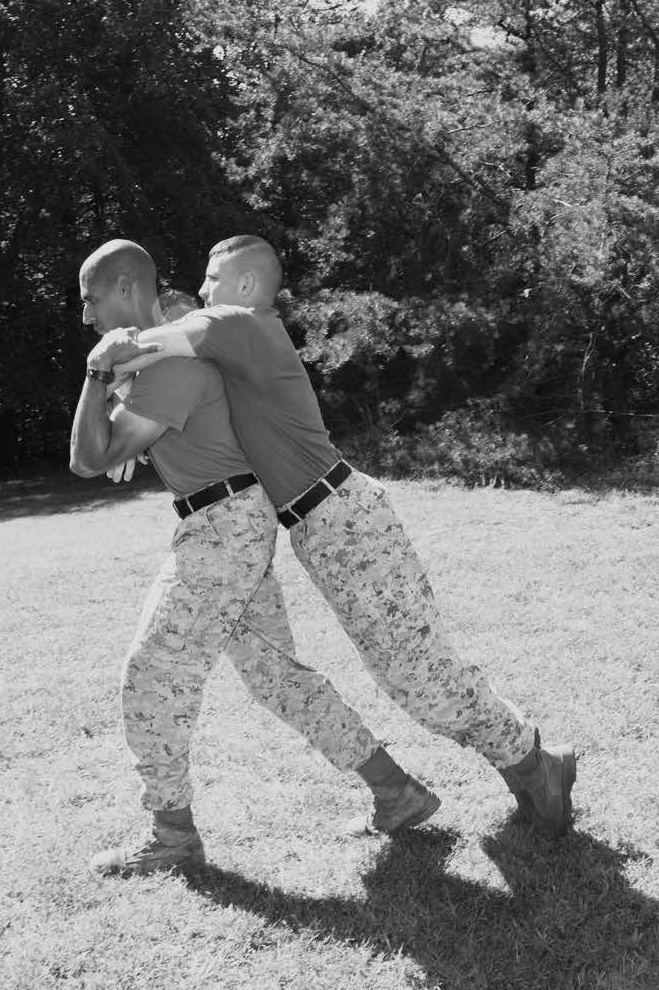

Cross-Body Carry. This movement exercise will begin with both Marines in the standing position. The Marine performing the carry will stand perpendicular to the Marine being carried. The Marine performing the carry will wrap one arm over the near shoulder, around the head, and under the armpit of the Marine being carried. (See Figure 9-82.) The Marine performing the carry will lean forward slightly, bending at the hips and maintaining a straight back and slightly bent knees. The Marine being carried will lie across the back of the Marine performing the carry. The Marine performing the carry will reach over legs of the Marine being carried and place the free arm around the other Marine’s legs, grasping the leg closest to the deck. The Marine performing the carry will straighten up, lifting the other Marine off the deck, and adjust the Marine being carried such that he is parallel to the deck and positioned at or above the hips of the Marine performing the carry. (See Figures 9-83 and 9-84.) On order, the Marine will rapidly carry the other Marine the designated distance. To prevent fatigue, shorter distances (25 meters or less) are preferred, and Marines may change roles at the halfway point.

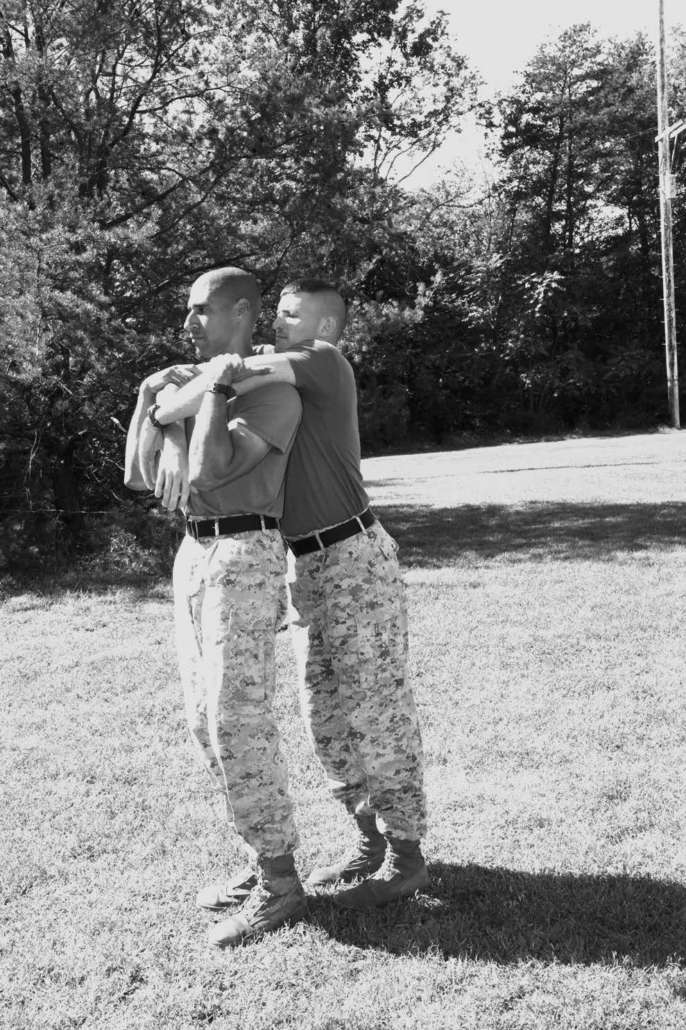

Buddy Drag. This movement exercise will begin with Marines covered-down and facing the direction of movement. The Marine standing in front of the other Marine and closest to the starting line will execute the carry. The Marine being carried will thrust both arms over the shoulders of the Marine performing the carry. Once in this position, the Marine being carried will lock the hands without interlocking the fingers. (See Figure 9-85.) The Marine performing the carry will ensure that his shoulders are seated in the armpits of the Marine being carried. The Marine performing the carry will grasp the wrists or forearms of the Marine being carried. (See Figure 9-86.) At no time will the forearms of the Marine being carried contact the neck or throat of the Marine performing the carry. Additionally, the feet of the Marine being carried will remain in contact with the deck; however, at no time will the Marine being carried place the soles of the feet on the deck. Further, at no time will the Marine being carried assist the Marine executing the drag. On order, the Marine will rapidly carry the other Marine the designated distance. (See Figure 9-87.) To prevent fatigue, shorter distances (25 meters or less) are preferred and Marines may change roles at the halfway point.

Piggy-Back. This movement exercise will begin with Marines covered-down and facing the direction of movement. The Marine standing in front of the other Marine and closest to the starting line will execute the carry. The Marine being carried will place the hands on the shoulders of the Marine performing the carry. The Marine performing the carry will lean forward slightly, bending at the hips and maintaining a straight back and slightly bent knees. The Marine being carried will jump onto the back of the Marine performing the carry and lock the hands, without interlocking the fingers, around the shoulders of the Marine performing the carry. The Marine performing the carry will reach over the legs of the Marine being carried and grasp the hamstrings or behind the knees. (See Figure 9-88.) The Marine performing the carry will straighten up, lifting the other Marine, and adjust the Marine being carried such that he is perpendicular to the deck and positioned at or above the hips of the Marine performing the carry. (See Figure 9-89.) At no time will the forearms of the Marine being carried contact the neck or throat of the Marine performing the carry. On order, the Marine will rapidly carry the other Marine the designated distance. To prevent fatigue, shorter distances (25 meters or less) are preferred, and Marines may change roles at the halfway point.

Bear Crawl. The Marine will begin by maintaining four points of contact with the deck: the hands and feet. The Marine will face the deck and move forward by placing the right hand and left foot forward. (See Figure 9-90.) Once both the hand and foot are on the ground, the Marine will move forward by placing the left hand and right foot forward. (See Figure 9-91.) The Marine will continue in this manner until the prescribed distance has been reached. The Marine performing the bear crawl will not stand up until the exercise has been conducted for the designated distance. At no time will the knees make contact with the deck.

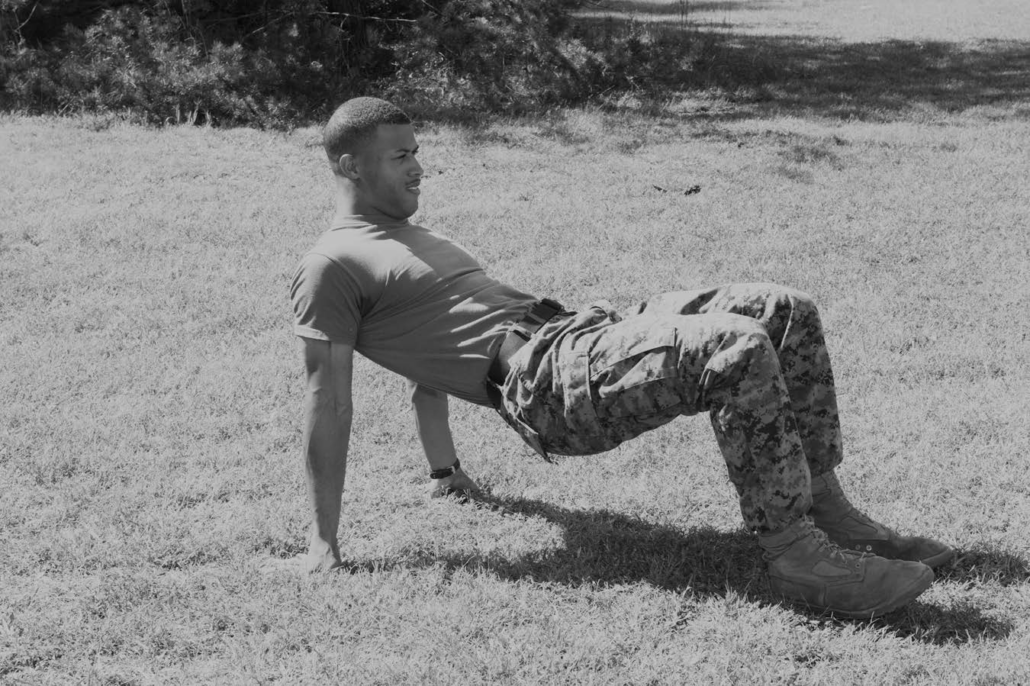

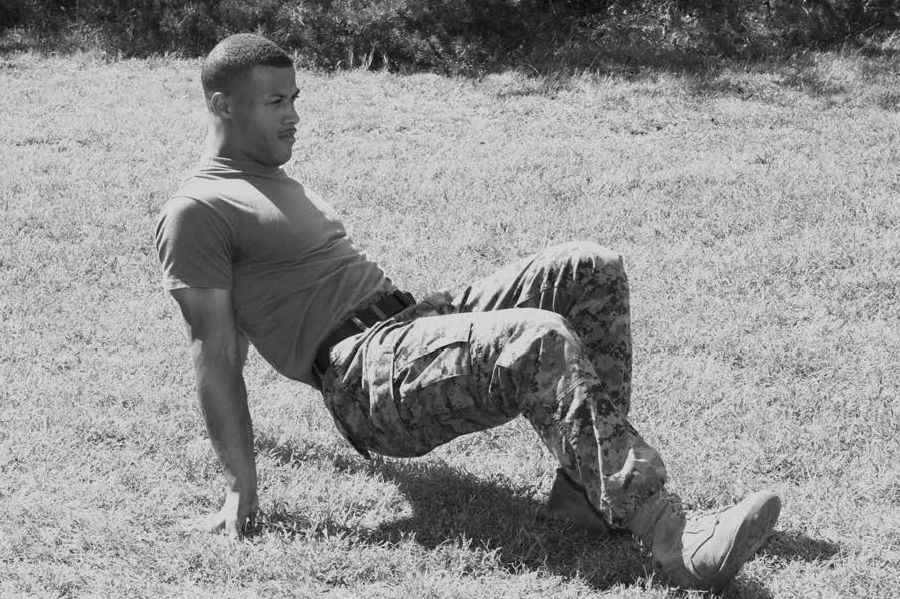

Crab Walk. The Marine will begin by maintaining four points of contact with the deck: the hands and feet. The Marine will face away from the deck, maintain elevated hips and support the body with only the hands and feet. The Marine will move forward by placing the left hand and right foot forward. (See Figures 9-92 and 9-93.) Once both the hand and foot are on the ground, the Marine will move forward by placing the right hand and left foot forward. The Marine will continue in this manner until the prescribed distance has been reached. The Marine performing the crab walk will not stand up until the exercise has been conducted for the designated distance. At no time will the Marine rest on the heels or allow the hips to contact the deck. Exercise variations include performing the crab walk laterally, as well as in a linear fashion.

General Aerobic Training

Aerobic training is often linked to endurance training. Such training requires aerobic, or oxygenated, energy pathways to supply fuel to each of the working muscles. Terms often used to describe aerobic training include: cardiovascular, cardiopulmonary, or cardio-respiratory endurance training because aerobic training significantly challenges the heart (cardio), blood vessels (vascular), and lungs (pulmonary or respiratory). The purpose of aerobic conditioning is to improve the efficiency with which the body produces energy for working muscles by means of aerobic metabolism. Quite simply, cardio-respiratory endurance training will improve aerobic energy production and lead to positive long- and short-term changes within the Marine’s body.

Within the first few weeks of beginning a cardio-respiratory endurance program, a Marine’s body will adapt to the various stresses placed upon it, resulting in a decreased heart rate whether resting or working, an increase in the amount of blood pumped by each heartbeat (stroke volume), and an increase in the amount of blood pumped by the heart in one minute (cardiac output). After engaging in a cardio-respiratory endurance program for more than 16 weeks, it is common for a Marine to possess an increased number of red blood cells, higher plasma volume in his blood, greater capillary density, weight loss, and a decreased resting heart rate.

To develop a proper cardio-respiratory endurance program, Marines must apply the combat conditioning principle of overload. By “shocking” his system and allowing adequate recovery, a Marine may improve aerobic fitness while simultaneously limiting the risk of injury and/or illness. Aerobic fitness requires three to five training sessions per week, at a moderate intensity, for a period of 20 to 60 minutes. Additionally, recent research indicates that aerobic exercise sessions may be separated into two or more sessions of at least ten minutes, resulting in significant cardio-respiratory endurance gains.

There are several different exercise modes that may enhance a Marine’s cardio-respiratory endurance, including, but not limited to: running, jogging, walking, swimming, cycling, rowing, and striding on an elliptical trainer. By cross training, or providing multiple aerobic activities in a single exercise program, a Marine may increase his cardio-respiratory endurance through a varied, rather than boring, workout. Besides reducing boredom, the physical conditioning principle of variety allows for more enjoyable physical training sessions.

Developing Cardio-Respiratory Endurance

Beginning an aerobic training program by imitating a friend or following a fitness magazine’s schedule may not necessarily be the best approach to developing cardio-respiratory endurance. Oftentimes, sample programs present idealized training that most people with jobs, families, and additional responsibilities cannot follow without significantly disrupting their lives. The most efficient training programs are individually tailored and incorporate long slow distance, pace, and interval training sessions.

- Long Slow Distance Training. Long slow distance training is conducted at an intensity of approximately 50 to 85 percent of one’s heart rate reserve (HRR). The HRR may be determined by subtracting the resting heart rate (the number of heartbeats per minute while at rest) from the maximal heart rate (220–one’s age). Long slow distance training should be performed for a duration ranging from 30 minutes to several hours. The main benefit of this type of training is improved energy production due to an increase in the amount of capillaries transporting oxygen and nutrients to the working muscles, as well as an increase in the number of mitochondria in each muscle cell.

- Pace Training. Pace training involves exercise sessions that are conducted at approximately the same pace in which one runs the semiannual PFT three-mile run or slightly faster. Pace training forces a Marine to push himself and challenges the Marine’s body to adapt. Just as in strength training, the body will respond to the demands placed upon it; if a Marine always runs at the same pace, the body will not be stimulated to adapt and become more efficient. Unlike long slow distance training, pace training relies on a combination of aerobic and anaerobic energy production. Training with high intensity will often cause a rapid increase in breathing rate, as well as a burning or heavy sensation in the working muscles. Such sensations are caused by an increased production of lactate, a product of anaerobic energy production. After an appropriate cool-down period, Marines may effectively remove lactate from muscles by participating in a comprehensive flexibility session. The main benefits of pace training are the improvement of one’s running economy and the understanding of how to run with high intensity.

- Interval Training. Interval training consists of short, high intensity bouts ranging in duration from 30 seconds to several minutes. The purpose of interval training is to condition one’s body to elevate performance and exercise at very high intensities. Much like sprinting at the end of a long distance run, interval training assists Marines in pushing beyond an already strenuous capacity. An interval session may consist of five to ten interval and recovery sessions. It is important to remember that interval training is very stressful. As such, after each interval session, an equal period of rest or low-intensity exercise should be allotted for recovery. Additionally, interval training should be limited to a small portion of one’s overall cardio-respiratory endurance training program. Interval training in excess not only results in fatigue but carries a heightened risk of injury as well.

Benefits of Cardio-Respiratory Endurance Training

A properly designed cardio-respiratory endurance training program, consisting of three to five sessions per week, will provide a Marine with a strong aerobic fitness level. By combining long slow distance, pace, and interval training, a Marine will likely maximize his performance during day-to-day physical activities, as well as during the semiannual PFT.

Semi-annual Physical Fitness Test and

Semi-annual Combat Fitness Test

For the most current information on the semi-annual Physical Fitness Test (PFT) and Combat Fitness Test (CFT), including male and female scoring and how to prepare for the tests visit the Marine Corps Force Fitness website at: https://www.fitness.marines.mil.

Negative Effects of Physical Training

Fatigue. In addition to muscular soreness and stiffness, the Marine who exercises for fitness will experience fatigue as a result of exertions. Fatigue is a feeling of tiredness that results from prolonged or intense physical or mental activity. Fatigue is a regulator in that it prevents us from damaging our body’s systems by overexertion (too much work). The accumulation of training fatigue can result in long term decrements in performance with or without the associated physical or mental signs and symptoms of maladaptation. This is called overtraining. Overtraining limits a Marine’s ability to increase physical performance and often results in degraded performance. It can take weeks or months to recover. Thus it is extremely important to be aware of indications of excessive fatigue. Fatigue may be neuromuscular, organic, or mental.

- Neuromuscular fatigue is indicated by cramps, heaviness in the limbs and failure of the muscular system to perform. It is temporary and normally not dangerous. Examples of neuromuscular fatigue would be the cramps in the stomach muscles when you’ve done just about your maximum in situps or the heaviness felt in your legs at the end of a long run.

- Organic fatigue is normally felt in the inner organs and is indicated by hyperventilation (uncontrollably high rate of breathing), heat illness (the failure of the body’s cooling system to maintain the normal temperature range), and nausea or other illness.

- Mental fatigue may be brought on by nervousness, low morale, depression, and lack of rest. Energy is spent on worry and through muscular tension. Chronic mental fatigue contributes to an inability to exert maximum physical effort. This lack of tolerance for effort is called the effort syndrome.

Fatigue is natural and normal. Everyone experiences it in one of its forms. It is important to be able to recognize fatigue because unchecked fatigue will lead to exhaustion and collapse. An example of exhaustion is the case of a runner who has gone far past the point of a good maximum effort, is starting to experience severe muscular pain and an inability to focus vision, is experiencing nausea, has a very high body temperature (104 degrees or higher), and is experiencing an uncontrollable shortness of breath. If that person continues to run, one or more body systems will fail and cause collapse. A good warning sign of overexertion is a strong pounding sensation in the temples of the individual with each pulse.

Sleep and Rest. Nature’s way of eliminating fatigue is through sleep and rest. Our need for sleep and rest is obvious, and the Marine Corps plans accordingly. Even during basic training, which may be the most demanding experience a Marine faces, each recruit normally receives a full eight hours of sleep. The sleep is necessary in order for a recruit’s body to recover from one training day and build its reserves of energy for the next.

- Sleep is a state of unconsciousness produced by the body’s central nervous system for the purposes of restoring and rebuilding its capabilities. The characteristics of sleep are relaxation of the muscles and of the mind. While all people do not require the same amount of sleep, eight hours are recommended for most young adults. Getting the proper amount of sleep is important. Too much sleep can cause you to be lazy. Too little sleep causes irritability and a reduction in the mental powers of reasoning and learning.

- Rest is a relaxation of the mind and body. The characteristics of rest are a lessening of physical and mental activities. The amount of time required for rest depends upon a person’s age, level of fatigue, and overall physical condition. An example of rest is the 10-minute break given during each hour of a forced march. Resting regularly during the day will increase both your effectiveness on the job and your enjoyment of your daily pursuits.

The Rewards of Physical Fitness

Physical fitness is not a gift; like the respect of your fellow Marines, physical fitness must continually be earned. It must be done by each individual Marine; no one can do it for you. Self-improvement requires a hard, determined effort; however, the reward is a strong, healthy body capable of accomplishing any mission, at any time, under any set of circumstances. This chapter presented basic concepts related to physical training for combat. For more information seek out a FFI, your NCOs, and visit www.fitness.marines.mil