U.S. Marines, Cuba, and the Invasion that Never Was: Part 1

By: Dr. Edward T. Nevgloski, Ph.D.Posted on August 15, 2023

In both open and back-channel discussions with Soviet officials, President Kennedy demanded the construction of the sites cease and that the missiles be removed. To convince Khrushchev of his resolve, Kennedy ordered a U.S. invasion force, including more than 35,000 Marines, into positions off Cuba and throughout the Caribbean in anticipation of having to take direct military action. Among the tasks assigned to the II Marine Amphibious Force in military contingency plans was the largest amphibious assault since Okinawa in 1945 aimed at seizing the Port of Havana and follow-on amphibious and ground asaults to expand the perimeter of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station. Drawn from documents maintained by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Md., and the Marine Corps archives at Quantico, Va., this article reveals—for the first time to many—the Marines’ roles in the planning and execution plan for the invasion that never was.

Marines and Initial Invasion Planning

The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved America’s first Cuba invasion plan in July 1959 following communist revolutionary Fidel Castro’s brutal six-year struggle to remove Fulgencio Batista from power. Designed by a multi-service team of planners in Admiral Robert L. Dennison’s U.S. Atlantic Command, Operation Plan (OPLAN) 312-60 called for a brief air campaign followed by an Army XVIII Airborne Corps’ assault on the Jose Marti and San Antonio de los Banos military airfields south of the capital at Havana. After 19th Air Force transports delivered additional Army ground forces to seize the Port of Havana, the Second Fleet’s Atlantic Amphibious Force would land an armored regiment at Regla inside the port to assist in capturing the capital. Planners later changed the armored regiment’s insertion from sea to air. After toppling Havana, the American ground force would have to clear all remaining pockets of resistance east to the Guantanamo Bay. Planners estimated it would take 30 days to complete the invasion.

The Marine Corps did not participate in OPLAN 312-60 planning and, in the event of an invasion, had no role other than defending the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station and providing fixed-wing attack squadrons for air strikes. It is unclear as to why Marines were more or less left out, though the most plausible explanation was President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s open animus toward the Marine Corps and the service’s diminished role in the national defense strategy. With the nuclear triad of missiles, submarines and bombers syphoning off most of Eisenhower’s defense budget beginning in 1953, the Marine Corps endured a more than $40 million budget cut and an end-strength reduction of over 60,000 Marines between 1954 and 1959. The Marine Corps’ 21st Commandant, General Randolph M. Pate, known more for his administrative acumen, overlooked his service’s bloated supporting establishment and deactivated six infantry battalions and six aircraft squadrons in 1959—a more than 30 percent reduction in combat strength—and left the remaining battalions and squadrons to function at 90 percent and 80 percent manning levels. Eisenhower’s misguided policies and Gen Pate’s misplaced priorities kept the Fleet Marine Forces chronically understrength and incapable of supporting contingency plans like OPLAN 312-60.

The Marine Corps’ scene changed dramatically in 1960 when General David M. Shoup became the 22nd Commandant. Restoring operational readiness as the service’s primary focus, Gen Shoup chose to downsize training and support commands and used a 3,000 Marine end strength increase authorized by newly elected President Kennedy one year later to bring the Fleet Marine Forces back to full capacity. Under Kennedy and Shoup, observed Marine Corps historian Edwin H. Simmons, “technical capabilities had caught up with doctrinal aspirations.” The likelihood that current events would lead the Joint Chiefs to modify the invasion plan were high as were the chances that the Marines would play a part given the changes as a result of Shoup’s operational focus and Kennedy’s defense strategy.

OPLANS 312-61 and 312-61 (Revised)

The January 1961 Department of Defense (DOD) study “Evaluation of Possible Military Courses of Action in Cuba,” outlining potential courses of action “in view of increased capabilities of the Cuban Armed Forces and militia” and the Soviet military buildup on Cuba was a clear indication that Marines would have a role in invasion planning and a possible invasion. Specifically, DOD officials included in the study the forces available for an invasion, namely the U.S. Atlantic Fleet’s “two carriers, a Marine Division, and a Marine Air Wing.” When Admiral Dennison reconvened invasion planning in February at the direction of the Joint Chiefs, he invited Fleet Marine Force Atlantic planners to help develop the ground scheme. The resultant OPLAN 312-61 added an amphibious assault by a Marine brigade to seize the Port of Havana.

Concepts derived from Major General Robert E. Hogaboom’s Fleet Marine Force Organization and Composition Boards in 1955 and 1956 offered planners integrated Marine air-ground forces at the expeditionary unit to force level for rapid deployment anywhere in the world by sea and air. With the prospects of a presidential decision to invade Cuba could come with little-to-no notice, the inclusion of fast landing forces, flexible emergency plans, and pre-loaded combat supplies on amphibious ships in contingency were now essential and part of every discussion.

Intelligence gleaned from the botched Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored Cuba invasion by anti-Castro exiles in mid-April 1961 brought Atlantic Command planners back together. Of particular concern were reports of Soviet-made tanks and antiaircraft systems and a Cuban ground force of upwards of 75,000 soldiers. In turn, planners produced OPLAN 312-61 (Revised). Remaining in were the air strikes, airborne assault on the military airfields, seizing Havana, and defeating all Cuban forces between the capital and Guantanamo Bay. The most significant change was an amphibious assault east of Havana and a series of land and sea-based attacks by II Marine Expeditionary Force. The Atlantic Amphibious Fleet commander, Admiral Alfred G. Ward, recalled, “We would plan on where the Marines would land, plan what cruisers would be needed in order to provide gunfire support, and what would be necessary to protect these landings.”

Concerned that President Kennedy might order military action with very little notice, the Joint Chiefs directed ADM Dennison to develop a more synchronized invasion scheme. Although the concept of operations and force composition remained intact, OPLAN 314-61 now had more elaborate time strictures governing force deployments, the air campaign, and the time between the airborne and amphibious assaults. The changes had no impact on II Marine Expeditionary Force’s plan completed during the summer of 1961.

II Marine Expeditionary Force Operations Plan 312-61

Marine Corps HUS-1 helicopters with HMR-262 take off from USS Boxer, during operations off Vieques Island with the 10th Provisional Marine Brigade, March 8, 1959. (Photo courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.)

II Marine Expeditionary Force’s involvement coincided with General Shoup’s directive that Fleet Marine Force Atlantic and Pacific headquarters also function as expeditionary force-level command elements during division/wing-level exercises and contingencies. Lieutenant General Joseph C. Burger, in addition to commanding Fleet Marine Forces Atlantic, activated and assumed command of II Marine Expeditionary Force in June 1961. Explaining to Leatherneck that same month that being “prepared to react in the shortest possible notice” was his focus, LtGen Burger oversaw the detailed planning and completion of both Fleet Marine Force Atlantic Operation Plan 100-60 and II MEF Operations Plan 312-61. Burger’s blueprint for keeping 25,000 Marines ready involved quarterly brigade-size amphibious assault exercises on Puerto Rico’s Vieques Island with several smaller exercises taking place at Camp Lejeune in between. Doing this kept one third of his units assigned to II Marine Expeditionary Force Operations Plan 312-61 embarked and within a few hours transit time from Cuba.

In the event that President Kennedy ordered an invasion, the II Marine Expeditionary Force owned four major tactical tasks; one within each of OPLAN 314-61’s four phases. In Phase I (Counter the Threat to Guantanamo and Prepare for Offensive Operations) LtGen Burger was responsible for defending the naval station. To do this, the battalion afloat in the Caribbean would land and immediately take up positions the length of the demarcation line separating the naval station from sovereign Cuba. Burger would then fly 2nd Marine Division’s “ready” battalion and a regimental headquarters directly to Guantanamo Bay where it would absorb an armor platoon, an engineer detachment, and an artillery battery deployed from Camp Lejeune as augments to the naval station’s permanent Marine Barracks.

With the 2nd Marine Division (minus those defending the naval station) and 2nd Marine Air Wing’s helicopter squadrons embarked on amphibious ships at Little Creek Amphibious Base near Norfolk, Va., and anchored off Camp Lejeune, N.C., the II MEF deployed to the Caribbean for Phase II (Position for Operations).

Once off Cuba, two helicopter squadrons had to relocate to Guantanamo Bay to support 2nd Marine Division elements there. Meanwhile, Marine fixed-wing squadrons transitioned to either aircraft carriers or to the Naval Air Station Key West, Fla., and the Naval Air Station Roosevelt Roads in Puerto Rico.

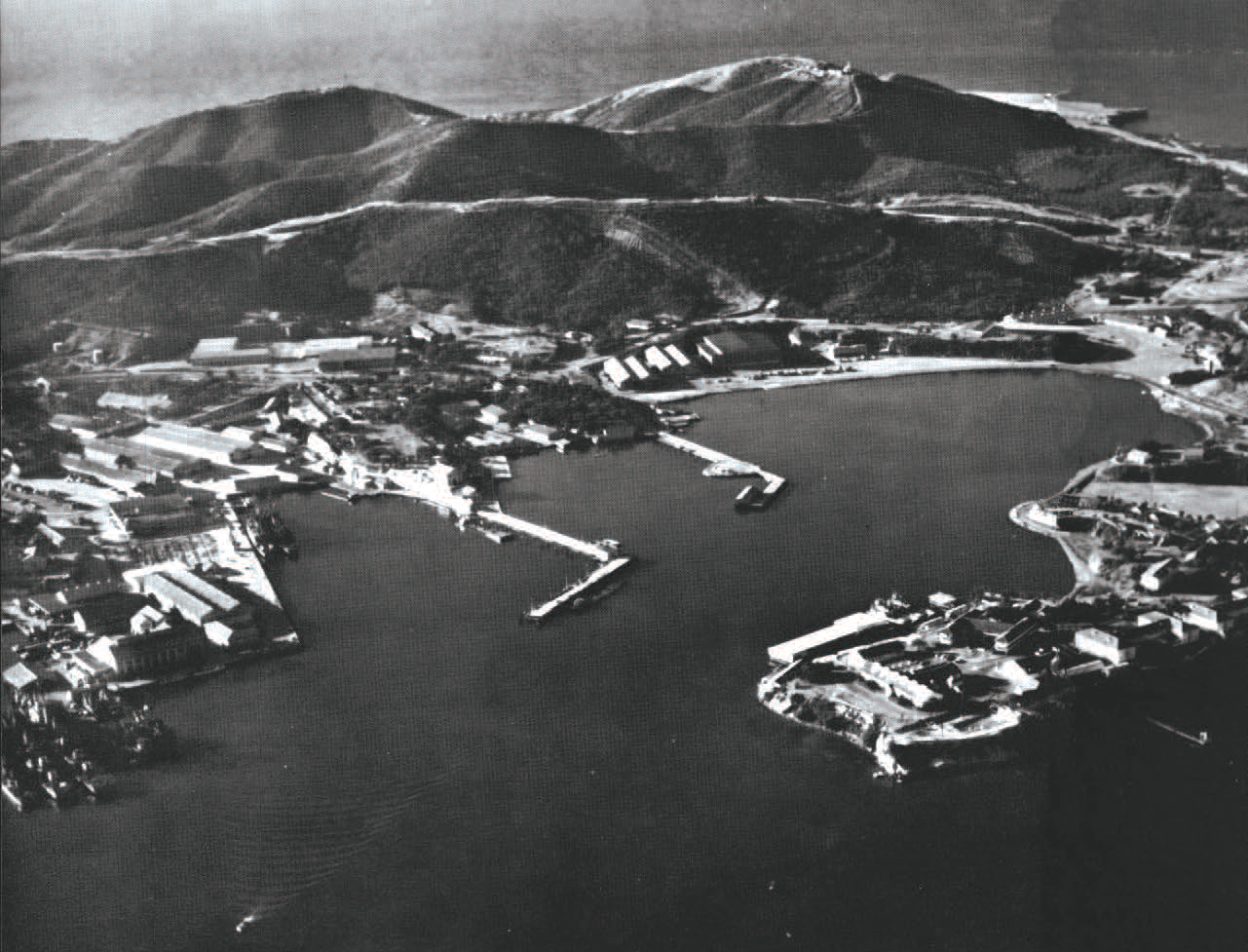

On the order to invade, 2nd Marine Air Wing’s fixed wing squadrons would strike Soviet and Cuban air defense systems and ground forces in and around Havana and near Guantanamo. As a counter to Cuban and Soviet infantry, armor, and mechanized formations defending Havana, planners tasked the Army’s 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions and the 1st Armored Division with landing 10 miles east at Tarara and sweeping southwest and then north into the capital. For this to happen, 2nd Marine Division, in Phase III (Assault Havana Area) and “in coordination with airborne and surface-landing of Army forces,” had to establish a beachhead at Tarara. The division’s two infantry regiments reinforced with engineers and armor and supported by an artillery regiment would then attack west to seize the Morro Castle and the Port of Havana.

During Phase IV (Assault Guantanamo Area) operations, the II Marine Force re-embarked amphibious ships for “assault landing operations” in conjunction with 2nd Marine Division elements attacking west from the Guantanamo Bay. A consolidated II MEF would then attack toward central Cuba and link up with the Army’s XVIII Airborne Corps and the 1st Armored Division. Planners assessed that major combat operations would take 60 to 90 days to complete.

President Kennedy and the Joint Chiefs grappled over invading Cuba. The Joint Chiefs’ perspective was that in addition to Castro’s growing military capability and ongoing Soviet military buildup, the failed CIA-sponsored invasion exposed gaps in Cuba’s defenses such that if an invasion were to happen, it should be sooner rather than later. Surprisingly, Gen Shoup disagreed. In his novel “The Best and Brightest,” journalist David Halberstam recalled how Shoup’s primary concern was the size of the invasion force needed to control the island and American casualties. To elaborate, Shoup placed a map of the U.S. on an overhead projector and covered it with a transparent map of Cuba. Drawing attention to Cuba’s vastly smaller size in relation to the U.S., he covered the two maps with a transparency containing a small red dot. When asked what the red dot represented, Shoup explained it was the size of Tarawa before adding, “It took us three days and 18,000 Marines to take it.” Whether or not Shoup influenced Kennedy’s decision is unknown. Talk of an invasion, however, subsided. By the summer of 1962, the U.S. and Soviet Union were once again on the brink of war.

Editor’s note: Read Part II of “U.S. Marines, Cuba, and the Invasion that Never Was,” in the October issue of Leatherneck.

Author’s bio: Dr. Nevgloski is the former director of the Marine Corps History Division. Before becoming the Marine Corps’ history chief in 2019, he was the History Division’s Edwin N. McClellan Research Fellow from 2017 to 2019, and a U.S. Marine from 1989 to 2017.