Core Values and Leadership

Core Values and Leadership

Every private in the Marine Corps serves as a potential squad leader. Every squad leader can become a sergeant major. These concepts have provided the Corps with the world’s finest body of small unit leaders since 1775. The backbone of the Marine Corps is its NCOs. Every one of them started as a private.

Marine Corps sergeants and corporals provide the most direct and personal leadership found anywhere. They do it in peacetime as well as in war. And like their forerunners of the “old Corps,” none of them was a “born leader.” They became leaders through hard work, skill, and a strict sense of duty.

All Marines embrace our basic Core Values of Honor, Courage, and Commitment, and our leaders must model them in all that they do. These values and their attributes are defined in detail on the next page. This chapter deals with character development of Marines and the principles and traits used to develop leadership. When you have developed them, you will have achieved as well that all-important sense of duty. The hard work is up to you. You will see that a leader with an ethical mindset knows right from wrong and has a firm moral compass that guides every action. You will begin to understand that this mindset cannot be developed in Marines at the moment of action; NCOs who demonstrate the steady resolve of a principled warrior must ingrain it beforehand. Marines must possess an ethical instinct to make instinctive decisions and an ethical mindset to frame the problem. It takes the moral and physical courage of a Marine to do the right thing.

If you are now a private, this chapter informs you what is expected of leaders in the Marine Corps. Study it, and be ready to take on the responsibilities of higher rank when they come your way. This era of the “Strategic Corporal” means that tactical decisions made on your part of the battlefield can affect the Marine Corps and the United States. Make no mistake; your actions do have an impact.

Warrior Ethos

Marines are warriors, and warriors are professionals and part of a profession of arms. It’s not just what we do; our ethos is who we are and what we believe. Although war is a violent, chaotic, and destructive environment, the Marine warrior is guided in all actions by principles and values that are embraced within the Corps and the Nation. For this reason, Marines have earned the trust and respect from those they serve and defend.

As Marines, we are distinguished by our commitment to our core values and our warrior ethos. Ethos means the distinguishing character, sentiment, moral nature, or guiding beliefs of a person, group, or institution. When we say we have a warrior ethos, it means we are focused on being warriors: “Marines fight and win–that’s what we do, that’s who we are. To be a Marine is to do what is right in the face of overwhelming adversity.” It’s upholding our core values and demonstrating honor through integrity; doing what is right, morally, and legally; taking responsibility for actions; and holding ourselves and others accountable.

Core Values

The Marine Corps formally established Honor, Courage, and Commitment as our core values in 1996. Our Core Values do not diminish our ability to fight and win; in fact, ethical conduct on the battlefield is a combat multiplier. As leaders, NCOs are responsible for making sure that their Marines understand the impact of ethical conduct on the mission of their unit and the Marine Corps. It is important to know that the battlefields may change, but our values will not. Modern war by its very nature, often blurs the lines between friend and foe, but our values remain constant. Our enemies may not be bound by the same rules we are and may kill without conscience—but that does not change who we are as Marines or what we believe in.

The success of the Marine Corps on the battlefields of today and the future will come as a result of the discipline and ethical conduct of the individual Marine. An ethical mindset in action in the operational environment is an absolute requirement. Knowing right from wrong and having a firm moral compass that guides your actions as a Marine cannot be developed in combat. It will be ingrained beforehand by leaders sustaining the foundation laid during recruit training, through realistic training, and by the commitment to excellence of every Marine.

Leadership Traits

You don’t inherit the ability to lead Marines. Neither is it issued. You acquire that ability by taking an honest look at yourself. See how you stack up against 14 well-known character traits of a Marine NCO. These are:

- Integrity.

- Knowledge.

- Courage.

- Decisiveness.

- Dependability.

- Initiative.

- Tact.

- Justice.

- Enthusiasm.

- Bearing.

- Endurance.

- Unselfishness.

- Loyalty.

- Judgment.

Set out to acquire those traits that you might lack. You improve those you already have, and you make the most of those in which you are strong. Work at them. Balance them off, and you’re well on the road to leading Marines in war or peace. Marines expect the best in leadership, and they rate it. Give them the best and you’ll find that you accomplish your mission and have the willing obedience, confidence, loyalty, and respect of your charges. In fact, you will have lived up to the official definition of a military leader.

Now, take a closer look at each of the character traits a leader must have.

1. Integrity. The stakes of combat are too high to gamble leadership on a dishonest person. Would you accept a report from a patrol leader who had been known to lie? Of course you wouldn’t. All your statements, official or unofficial, are considered by your Marines to be plain, unadorned fact. When you give your word, keep it. Do what is right legally and morally. Many others will depend upon you.

2. Knowledge. Know your job, weapons, equipment, and techniques to be used. Master this Guidebook and your other training material. Be able to pass on that knowledge to your Marines. You can’t bluff them. They are expert at spotting a fake. If you don’t know the answer to a question, admit it. Then find out. Most important, know your Marines. Learn what caliber of performance to expect from each of them. Put confidence in those who you can. Give close supervision to those who need it.

3. Courage. This comes in three kinds: mental, moral, and physical. If you are in a tight place and feel fear, recognize it. Then get control over it and make it work for you. Fear stimulates the body processes. You can actually fight harder, and for a long time, when you are scared. So don’t let a little fear make you panic inside. Your physical strength comes from personal conditioning and your ability to withstand hardships in any clime or place. Keep busy when under fire. Fix your mind on your mission and your Marines. Courage grows with action. When things are really tough, take some action, even if it only amounts to a gesture or a distraction for you or your Marines.

As for moral courage, know what’s right and stand up for it. Marines are not plaster saints by any means. But they serve God, Country, and Corps and maintain their warrior spirit. A combat leader also must be a moral leader.

When you’re wrong, say so and openly. Don’t try to evade your mistake. Everybody makes a mistake now and then. The trick is not to make the same one twice. When a job is left undone, true leaders don’t harp, “Sir, I told those people … ” They fix the breakdown, instead of blaming. Be prepared to take responsibility.

4. Decisiveness. Get the facts, all of them. Make your mind up when you’ve weighed them. Then issue your order in clear, confident terms. Don’t confuse your Marines by debating with yourself out loud. Say what you mean, and mean what you say. Make up your mind in time to prevent the problem from becoming bigger, but don’t act with half-thought ideas. If the decision is beyond the scope of your authority, take the problem up the chain of command to the person authorized to make that decision. But if the decision is yours, make it. Don’t pass the buck.

5. Dependability. If only one word could be used to describe Marine NCOs over the years, that one word would have to be “dependable.” They accomplish the job, regardless of obstacles. At first, they may not agree with the ideas and plans of their seniors. Being dependable, if they have a better plan, they tactfully say so. But once the decision comes, they carry out the tasks to the best of their ability, whether or not it was their own plan that went into effect. Follow orders to the letter, in spirit, and in fact. The mission comes first, then the welfare of their Marines, then their own requirements.

Dependable NCOs are solid citizens. They’re always on time, never make excuses and stay hot on the job until it’s done. They’re on board when needed and out of the way but ready when not needed. Duty demands that they often make personal sacrifices. They sense what has to be done, where duty lies.

6. Initiative. Think ahead. Stay mentally alert and physically awake. Look around. If you see a job that needs to be done, don’t wait to be told. If the barracks shows the clutter of newspapers and food wrappers on a Sunday morning, organize a detail and get the place squared away. Your situation and the lot of your Marines can always be improved. Do what you can. Use the means at hand. Think ahead, and you’ll stay ahead.

7. Tact. The right thing at the right time, that’s what we mean by tact. It embraces courtesy, but it goes much further. It’s the Golden Rule; consideration for others, be they senior or subordinate. Courtesy is more than saluting and saying “Sir” or “Ma’am.” It doesn’t mean you meekly “ask” your Marines to do a job, either. You can give orders in a courteous manner which, because it is courteous, leaves no doubt that you expect to be obeyed. The tactful leader is fair, firm, and friendly. You always respect another’s property and person. Learn to respect human life, dignity, customs, and courtesies as well. If an individual needs counseling then do it—but in private. Don’t make a spectacle of them and yourself by doing it in public. On the other hand, when they do a good job, let their friends hear about it. They will be a bigger person in their eyes, and you will too.

There are times, particularly in combat, when a severe “dressing down” of one person or a group of people may be required. Even so, this is tactful, when it is the right thing at the right time.

In dealing with seniors, the Golden Rule again applies. Approach them in the manner you would want to be approached were you in their position with their responsibilities.

When you join a new outfit, just keep quiet and watch for a while. Don’t assert that your old outfit was a better one just because it happened to do things differently. Make a few mental notes when you find something that is wrong. When you have established yourself, make those changes that you have the authority to make.

8. Justice. Marines rate a straight-shooting leader. Be one. Don’t play favorites. Spread the liberty and the working parties around equally. Keep anger and emotion out of your decisions. Get rid of any narrow views that you may have about a particular race, creed, or section of the country. Judge individuals by what kind of Marines they are; nothing else.

Give your Marines a chance to prove themselves. Help those who fall short of your standards, but keep your standards high.

9. Enthusiasm. The more you care about something, the greater your interest and enthusiasm. Show it. Enthusiasm is more contagious than the measles. Set a goal for your unit, and then put all you have in the achievement of that goal. This is particularly applicable in training. Marines are at their best when in the field. After all, they joined the Corps to learn how to fight. They’ll learn, all right, but only when their instructor is enthused about what is being taught. Show knowledge and enthusiasm about a subject, and your troops will want that same knowledge. Show your dislikes and gripe about what’s going on, and you’ll still be leading—but in the wrong direction. The choice is yours.

Don’t get stale. “Take your pack off” can sometimes be good advice. Do it once in a while. Rethink your issues and then come back strong with something new. When you find yourself forced to run tactical problems over the same old terrain, run them from the other direction.

10. Bearing. Think of drill instructors: lean, leather-lunged, and firm. With superb posture and impeccable uniform, they didn’t walk, they marched! And they taught you to do the same. You learned from them that a uniform is more than a mere “suit of clothes.” You wear a suit—but you believe in a uniform. Therefore, you maintained it—all the time. Every stripe, every ribbon, every piece of metal that you see on a Marine was earned. You earned your uniform and everything on it. Wear it with pride.

That’s part of what is meant by bearing. The rest of it is how you conduct yourself, in or out of formation, ashore or on board, verbally and emotionally. Manage your voice and gestures. A calm voice and a steady hand are confidence builders in combat. Don’t ever show your anxiety over a dangerous situation, even if you feel it.

Speak plainly and simply. You’re more interested in being understood than in showing off your vocabulary. If you ever rant and rave, losing control of your tongue and your emotions, you’ll also lose control of your Marines. Swearing at subordinates is unfair. They can’t swear back. It’s also stupid, since you admit lack of ability to express displeasure in any other way. There may be one exception to this rule. The time might come, in battle, when tough talk, a few oaths and the right amount of anger is all that will pull your outfit together. But save your display of temper until it is absolutely needed. Otherwise, it won’t pay off because you’ll already have shot your bolt.

Sarcasm seldom gets results. Wisecrack to Marines—they’ve been around—they’ll wisecrack back. Make a joke out of giving orders, and they’ll think you don’t mean what you say. This doesn’t mean to avoid joking at all times. A good joke, at the right time, is like good medicine, especially if the chips are down. As a matter of fact, it is often the Marine Corps way of expressing sympathy and understanding without getting sticky about it. Many wounded Marines have been sent to the rear with a concerned smile, a grasp, and a remark about, “What some people won’t do to get outta’ work!”

Dignity, without being unapproachable—that’s what bearing is. Work at it.

11. Endurance. A five-foot Marine sergeant once led his squad through 10 days of field training in Japan. He topped it off with a two-day hike, climbing Mt. Fuji on the 36 miles back to camp. When asked how a man of his size developed such endurance, he said, “It was easy. I had 12 guys pushing me all the way.” What he meant, of course, was that 12 other Marines were depending on his endurance to pull them through. He couldn’t think about quitting. Leaders must have endurance beyond that of their troops. Squad leaders must check every fighting position and then go build their own. On the march, they often will carry part of another’s load in addition to their own. An unfit body or an undisciplined mind could never make it.

Keep yourself fit, physically and mentally. Learn to stand punishment by undertaking hard physical tasks. Force yourself to study and think when tired. Get plenty of rest before a field problem. Don’t stay on liberty until the last place is closed. The town will still be there when you get back. A favorite saying of Marines is that you don’t have to be trained to be miserable. That’s true. But you do have to train to resist misery.

12. Unselfishness. Marine NCOs don’t pull the best rations from the case and leave the rest to their Marines. They get the best they can for all unit members all the time.

Leaders get their own comforts, pleasures, and recreation after troops have been provided with theirs. Look at any chow line in the field. You’ll see squad leaders at the end of their squads. You’ll find staff noncommissioned officers (SNCOs) at the end of the company. This is more than tradition. It is leadership in action. It is unselfishness.

Share your Marines’ hardships. Then the privileges that go with your rank will have been earned. Don’t hesitate to accept them when the time is right, but until it is, let them be. When your unit is wet, cold, and hungry—you’d better be too. That’s the price you pay for leadership. Give credit where credit is due. Don’t grab the glory for yourself. Recognize the hard work and good ideas of your subordinates and be grateful you have such Marines. Your leader will look after you in the same way. They know the score, too.

13. Loyalty. This is a two-way street. It goes all the way up and all the way down the chain of command. Marines live by it. They even quote Latin for it—Semper Fidelis. As a leader of Marines, every word, every action must reflect your loyalty—up and down. Back your Marines when they’re right. Correct them when they’re wrong. You’re being loyal either way. Pass on orders as if they were your own ideas, even when they are distasteful. To rely on the rank of the person who told you to do the job is to weaken your own position. Keep your personal problems and the private lives of your seniors to yourself. But help your Marines in their difficulties, when it is proper to do so. Never criticize your unit, your seniors, or your fellow NCOs in the presence of subordinates. Make sure they don’t do it either. If deserving persons get into trouble, go to bat for them. They’ll work harder when it’s all over.

14. Judgment. This comes with experience. It is simply weighing all the facts in any situation, application of the other 13 traits you have just read about, then making the best move. But until you acquire experience you may not know the best move. What, then, do you use for experienced judgment in the meantime? Well, there are more than 200 years’ worth of experienced judgment on tap in the Marine Corps. Some of it is available to you at the next link in the chain of command. Be a good observer of these leaders. Ask, and you’ll receive. Seek, and you’ll find.

Leadership Principles

Now that you’ve had a look at the character building leadership traits required of Marine leaders, let’s see how these are fitted into what we call the Leadership Principles. The Marine Corps has set forth eleven principles and is not concerned as much about the words and phrases as we are about their application. They’re all common sense items, anyway, and when you get right down to it, a discussion of leadership is only common sense with a vocabulary.

1. Set the example. As a leader, you are in an ideal spot to do this. Marines are already looking to you for a pattern and a standard to follow. No amount of instruction and no form of discipline can have the effect of your personal example. Make it a good one.

2. Develop a sense of responsibility among your subordinates. Tell your Marines what you want done and by when. Then leave it at that. If you have junior leaders, leave the detail up to them. In this way, kill two birds with one stone. You will have more time to devote to other jobs, and you are training another leader. A leader with confidence will have confidence in subordinates. Supervise and check on the results. But leave the details to the person on the spot. After all, there’s more than one way to skin a cat. And it’s the whole fur you’re after, not the individual hairs.

3. Seek responsibility and take responsibility for your actions. The leader, alone, is responsible for all that the unit does or fails to do. That sounds like a big order, but take a look at the authority that is given you to handle that responsibility. You are expected to use that authority. Use it with judgment, tact, and initiative. Have the courage to be loyal to your unit, your Marines, and yourself. As long as you are being held responsible, be responsible for success, not failure. Be dependable.

4. Make sound and timely decisions. Knowledge and judgment are required to produce a sound decision. Include some initiative and the decision will be a timely one. Use your initiative and make your decisions in time to meet the problems that are coming. If you find you’ve made a bum decision, have the courage to change it before the damage is done. But don’t change the word any more than you absolutely have to. Nothing confuses an outfit more than a constant flow of changes.

5. Employ your unit in accordance with its abilities. Don’t send two Marines on a working party that calls for five. Your Marines may be good, but don’t ask the impossible. Know the limitations of your outfit, and bite off what you can chew. In combat, a “boy sent to do a man’s job” can lead to disaster. In peacetime, it leads to a feeling of futility. Conversely, those who have a reasonable goal and then achieve it are a proud lot. They’ve done something and done it well. Next time, they’ll be able to tackle a little more. Don’t set your sights clear over the butts; keep them on the target.

6. Be technically and tactically proficient. Know your job. This requires no elaborations. It does require hard work on your part. Stay abreast of changes. Techniques, Tactics, and Procedures (TTPs) are constantly being changed and updated. Stay up-to-date on the latest weapons and equipment. Stay current with international and national news and recent developments in the Marine Corps and other services.

7. Know yourself and seek self-improvement. Evaluate yourself from time to time. Do you measure up? If you don’t, admit it to yourself. On the other hand, don’t sell yourself short. If you think you’re the best leader in your platoon, admit that also to yourself. Then set out to be the best leader in the company. Learn how to speak effectively, how to instruct, and how to be an expert with all the equipment that your unit might be expected to use.

8. Know your Marines and look after their welfare. Loyal NCOs will never permit themselves to rest until their unit is bedded down. They always get the best they can for their Marines by honest means. With judgment, you’ll know which of your troops is capable of doing the best job in a particular assignment. Leaders share the problems of their Marines, but they don’t pry when an individual wants privacy.

9. Keep your Marines informed. Make sure your Marines get the word. Be known as the person with the “straight scoop.” Don’t let one of your unit be part of the so-called “10 percent.” Certain information is classified. Let your Marines have only that portion that they need to know but make certain they have it. Squelch rumors. They can create disappointment when they’re good but untrue. They can sap morale when they exaggerate enemy capabilities. Have the integrity, the dependability to keep your unit correctly posted on what’s going on in the world, the country, the Corps, and your unit. Never forget that the more your Marines know about the mission that has been assigned the better they will be able to accomplish it.

10. Ensure that the task is understood, supervised, and accomplished. Make up your mind what to do, who is to do it, where it is to be done, when it is to be done, and tell your Marines why, when they need to be told why. Continue supervising the job until it has been done better than the person who wanted it done in the first place ever thought it could be.

11. Train your Marines as a Team. Train your unit as a unit. Keep that unit integrity every chance you get. If a working party comes up for three, take your whole fire team. The job will be easier with an extra hand, and your unit will be working as a team. Get your Marines on liberty together now and then. They work as a team; get ‘em to play as one. Put your Marines in the jobs they do best, then rotate them from time to time. They’ll learn to appreciate the other person’s task as well. When one member of your team is missing, others can do that share, but don’t ever permit several Marines to do another person’s job when they’re around. Everybody pulls their load in the Marine Corps.

When you and your unit have done something well, talk it up. This builds esprit de corps. You can’t see it, but you can feel it. An outfit with a lot of esprit holds itself in very high regard while sort of tolerating others. There’s nothing wrong with that. All Marines have a right to figure their unit is the best in the entire Corps. After all, they’re in it!

What You Can Expect as a Leader

We’ve spent some time on what the Corps expects of you as a junior leader. Remember, Marines are warriors, and warriors are professionals, and as professionals, the NCOs have the toughest tasks of all. NCOs are charged with upholding our core values and demonstrating honor through integrity; doing what is right, morally, and legally; taking responsibility for actions; and holding yourself and others accountable. In garrison, you are tasked with the maintenance of good order and discipline. In combat, you make hard decisions—often in a split second. However, it’s not all one way. There are certain things that you have a right to expect in return. First of all, since you are the link in the chain of command that lies squarely between your senior and your subordinates, you can expect the same leadership from above that you’ve just read about.

Then there’s the additional pay you’ll be getting along with every promotion—and promotion comes to real leaders, regularly. Also with promotion comes additional authority. It’s granted to you on a piece of paper known as a Certificate of Appointment, commonly called a warrant. When you get one, take the time to actually read it and digest what it says.

You’ll see more there than simply a piece of paper—much more. First, there’s an expression of “special trust and confidence” in your “fidelity and abilities.” That is recognition of the highest order. It says you are a professional. It’s appreciation for your hard work thus far. But look further. You don’t rest on your laurels in the Marine Corps. There’s a charge to “carefully and diligently discharge the duties of the grade to which appointed by doing and performing all manner of things thereunto pertaining.” That means additional responsibility, which, when you think about it, is also a reward.

Next, you’ll find that additional authority we mentioned a while back. It’s in the words, “and I do strictly charge and require all personnel of lesser grade to render obedience to appropriate orders.” Commanding officers who sign that Certificate are delegating a part of their authority to you. They get their authority from the President of the United States and have chosen you to help them in the execution of their responsibility. Notice, however, that they haven’t delegated their responsibility to you or to anybody.

When it comes to leadership, there is no truer statement. Only the NCO is in a position to give the close, constant, personal type of leadership that we’ve been discussing. When you, as a Marine NCO, have provided your unit with that type of leadership, then you already will have reaped the greatest return. By definition, you’ll (1) have accomplished your mission and (2) command the willing obedience, confidence, loyalty, and respect of the U.S. Marines under you. There is no more satisfactory reward, anywhere.

Marine Leader Development Program

Sponsored by Education Command’s Lejeune Leadership Institute, the Marine Leader Development (MLD) program directs and encourages leaders to engage their Marines across the six functional areas of fidelity, fighter, fitness, family, finances, and future as a comprehensive approach to foster development of all aspects of Marines’ personal and professional lives. The “teach, coach, counsel, mentor” model provides the framework for leader-led developmental discussions to occur and sets the conditions for engagements on career goals/plans. The MLD directs a combination of required and event-driven engagements between leaders and Marines across the six Fs, with supporting resources and tools found at https://usmcu.edu/lli/marine-leader-development.

The Components of the Decision Cycle (OODA) Process

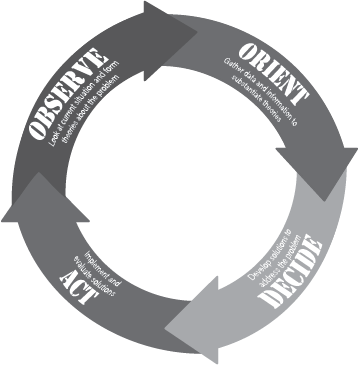

Boyd’s decision cycle is the constantly revolving cycles that the mind goes through when dealing with tasks that range from the mundane to the most complicated. This cycle follows the pattern of Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA). (See Figure 4-1.) Boyd theorized that each party to a conflict first observes the situation. On the basis of observation, one orients; that is, makes an estimate of the situation. On the basis of the orientation, one makes a decision. Finally, one implements the decision—acts. Because their action has created a new situation, the process begins anew. Boyd argued that the party who consistently completes the cycle faster gains an advantage that increases with each cycle. The enemy’s reactions become increasingly slower by comparison and, therefore, less effective until, finally, the enemy is overcome by events.

Observation, the first step in the ooda loop is a search for information relative to the tactical situation. Information could include the environment, enemy tactics, techniques, and procedures. It is an active effort to seek out all the available information by whatever means possible.

During orientation, the Marine uses information to form an awareness of the circumstances. As more information is received, the Marine updates the perceptions as needed. Orientation helps to turn information into understanding. It is understanding that leads to making good decisions.

Decide on a course of action. This is a conscious activity following orientation. The decision is based upon your perceived observations, training, experience, rules of engagement (ROEs), orders, and directives. Through repetitive training, some decisions can become automatic or reflexive.

An act is the implementation of the decision. It is crucial to understand the action taken will influence the environment, potentially changing it. This change in the environment will require that Marine to recycle through the OODA loop process. Instead of remaining fixated on the object, the Marine reassesses the situation.

The Dangers of Social Media

Remember that you are a Marine 24/7—in person and online. Participation on these sites makes you “the Marine Corps”—your conduct is a direct reflection of the Marine Corps. The best advice is to approach online communication in the same way we communicate in person—by using sound judgment and common sense; adhering to the Marine Corps’ core values of honor, courage, and commitment; following established policy; and abiding by the UCMJ.

Violations of federal law and DOD regulations or policies may result in disciplinary action under the UCMJ.

Dangers associated with social media include but are not limited to:

- Divulging Personal Identifiable Information (PII) that could be used by the enemy/threats (e.g. family info, address, telephone number, email address, etc.).

- Inadvertently exposing unit information (e.g. deployment schedule, troop movements/locations, size, capabilities, etc.).

- Susceptibility to hacking, phishing, malware, spyware, viruses, etc.

- Friends unknowingly make you vulnerable (privacy issue).

- Identity thieves.

- Fake profiles.

- Third party sharing/selling of your information.