German Training and Tactics

Posted on July 23,2019Article Date Oct 01, 1983

THE INTERVIEWERS (Billets held at time of interview)

Col Francis Andriliunas, Marine Liaison Officer, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command

Maj William B. Blackshear, Armor and Mechanized Instructor, Marine Corps Education Center

Maj Wellington H. Gordon, Head, Infantry Officers Course, The Basic School

LtCol Hans R. Heinz, Deputy Director, Amphibious Warfare School

LtCol Robert E. Kiah, Jr., Chief, Academic Plans and Doctrinal Review, Amphibious Instruction Department, MCEC

LtCol James M. Rapp, Chief, Supporting Arms Instruction Department, MCEC

Col William T. Sweeney, Assistant Chief of Staff, Amphibious Instruction, MCEC

LtCol M.D. Wyly, Head, Tactics Division, Amphibious Warfare School

The professional warrior must be willing to look outward. . . Ideas, techniques, and philosophies of other armies are always of interest. We are indebted to the staff of the Education Center, and particularly to LtCol M. D. Wyly, for providing these extracts from an interview held with a retired German officer.

Napoleon Bonaparte, mastermind of more decisive victories than any of us today has experienced battles, offered this counsel for those who might desire to follow him as serious students of warfare:

Read and reread the campaigns of Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne, Prince Eugene, and Frederick the Great. The history of those 88 campaigns, carefully written, would be a complete treatise on the art of war; the principles that ought to be followed in offensive and defensive war would flow from it spontaneously.

Napoleon advocated studying and even copying methods of foreign armies. Though he epitomized the nationalist, he chose not to narrow the focus of his studies to war as waged by his own countrymen. The professional warrior must be willing to look outward as well as inward. Ideas, techniques, and philosphies of other armies are always of interest. If we only study Americans or Marines, that is, if we only look inward, the foreseeable result would be that our views would become narrower and narrower. Our tactics would become increasingly predictable; our forces, more vulnerable.

In order to do the opposite, that is broaden our perspectives, the Marine Corps Education Center, Quantico, on learning that Col Hans Gotthard Pestke, a retired German officer with firsthand experience fighting the Soviets, was visiting in this country, dispatched a team of officers to ask him questions about training and tactics.

Col Pestke was visiting his daughter, whose husband, an active duty Bundeswehr colonel, was assigned to the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command at Fort Monroe, Va. His combat experience is extensive, and we were particularly pleased that he agreed to interrupt his vacation for an interview. In his insights, we were to discover a wealth of useful ideas.

Col Pestke’s comments are of particular interest because much has been written in military journals over the last few years about German tactics and maneuver warfare. His answers to questions validated many of the things that have been said. He also gave us a more complete understanding of the German model and its similarities and differences compared to U.S. Services. Most important, Col Pestke provided some professional notes from which all Marines may profit.

On meeting Col Pestke, we were immediately impressed with his military bearing. Though his dress might have identified him as a lawyer or banker, his bearing clearly marked him a soldier. He is tall, lean, and erect. His haircut would easily pass any U.S. Marine inspection. He is extremely alert and personable, appearing a good 10 years younger than he is. Though retired 10 years ago from the Service, he is still a professional. Because of experiences as a soldier and in his civilian profession, leadership and future development of land forces doctrine became his main interest in life. He discussed military history and his experience in combat with the authority of one who is thoroughly knowledgeable of the art of war. And, when doing so, his face, voice, and mannerisms combined to convey vividly that this is the subject of his interest.

The panel had prepared a list of questions which Col Pestke had read in advance. However, as the conversation progressed and the participants relaxed, many of the questions and answers became impromptu.

We used an interpreter as Col Pestke prefers to speak in German, in order to convey as precisely as possible his intended meaning. We perceived that he understands English well, as often he had his answers ready before the interpreter intervened.

Col Pestke asked to make an opening remark. He told us that he was honored to be queried about the profession of arms by U.S. Marines. He wanted us to know of the tremendous respect that he has always had for our Corps. He felt a kinship with us as brother warriors. He quoted a remark made by Charles de Gaulle in 1962 at the German Armed Forces Staff College in Hamburg: “We had a duty to be enemies. Now we have the privilege and right to be friends.”

What is the most important ingredient of a greate army?

Most of all, the individual soldier must be motivated. He must know why he is fighting and why he must defeat the enemy. He must understand and believe in the mission of his unit-the mission of his army. Only in this way will the organization function as one.

It would seem, then, that much must depend on the junior leaders in order to achieve that kind of motivation. How should young NCOs be trained and prepared to motivate their men properly?

First, they must be trained to make decisions on their own. That is, they must understand the concept of mission orders. You will find this to be a common thread woven throughout my answers. Mission orders require the strictest kind of discipline on the one hand, but on the other hand, and equally important, is the soldier’s capability to act on his own and to perceive the bigger picture.

Second, the NCOs and their soldiers must feel superior to the enemy. They must have confidence that they are superior, mentally and physically.

Third, they must have confidence in their commanders.

Fourth, the soldier must be given good equipment and a dependable logistics system.

And finally, soldiers, NCOs and officers must know that they can depend on each other. There must be a feeling of camaraderie.

I can see that NCOs would be particularly important when you attach so much importance to the motivation of even the youngest soldiers. Have you any opinions on special requirements for senior leaders?

Yes, but I would like to come back to that later. Most important is to understand that the Bundeswehr uses a system where the decisions are not always made vertically. There must be decisions made at each level of command.

It must be said in regards to the senior leaders that they should never forget that they have to bear the responsibility for each and every one of their subordinates. The subordinates must also be aware of this.

You have stressed the importance of decision-making ability among juniors. How do you train for this?

You must let young officers make decisions. They must be given the chance to make on-the-spot decisions, through wargames, that is, terrain models and map exercises. When a young soldier makes a decision, you must praise him. He might not have found the perfect or right solution, but he made a decision. Praise at this point must be forthcoming. You must do this again and again. That is how we give our young officers and NCOs confidence.

How do you make your training realistic, as a preparation for war?

If you really want to find out the capability of a man, put him under stressful situations and then give him some missions where he must demonstrate that he still has the capability to make decisions while taking care of his soldiers. If he can do this, he will probably be a good leader in combat. Of course, you cannot approximate the conditions of war. The eye and the mouth of a good critical umpire are more important than 10 simulated detonations.

Training of junior leaders must begin, I suppose, with a good, sound course in fundamentals. Wouldn’t this have to precede exercises in decisionmaking?

Here, I would disagree. Wherever possible, there must be training for the decisionmaking process. As Clausewitz has said, “One has to see the whole before seeing each of its parts.” The quality of the German NCO in World War II, of course, was the fact that he was not just able to lead his squad, but that he could make a valuable contribution by thinking himself into the position of the platoon or even the company commander. A squad leader must be able to lead his squad and to employ his weapons effectively, but this is not enough. He must be able to lead a platoon. He must be able to think on the level of the company. This system is characteristic of all German Army command levels, past and present.

We asked our squad leaders outright to know the mission two echelons up. During map exercises we demanded: “Answer me. What are the intentions of the next higher commander and what is your mission?” If he knows this, he is able to fulfill mission type orders.

How do the staffing procedures, the decisionmaking process in the German Army of today, compare with those of the German Army of World War II?

Up to the corps-level command, that of today compares favorably with that we experienced in World War II. Above corps level, it becomes a problem. There is a bureaucratic sluggishness simply because the German Army today must consider two points at this higher level. One is cooperation with the Allies and the other is the bureaucratic and political administrative jungle that one has to plow through in order to perform. As a soldier, this second problem is often extremely frustrating.

What about Soviet command and control techniques?

There is, in my opinion, one large difference. In the Soviet Army, unmitigated obedience absolutely dominates. In the Second World War, the Russian soldier was more afraid of punishment than he was of the enemy soldier. Whether it is that way today, I cannot say. I do know that during World War II we had a great advantage over the Russians because their lower levels could not make decisions. They could not react to us. Later on, however, especially by 1943, our army began to develop similar problems. Because of our high losses we had to train rapidly and this in turn caused the quality of replacements to suffer. Leadership ability declined.

Could you comment on “unit cohesion” and its effect on the performance of the army?

As far as my experience goes, the Reichswehr, the 100,000-man army, was a tightly-knit, excellent force. Perhaps one could compare it with the U.S. Marine Corps because it had the capability to be selective when choosing personnel. The Reichswehr also conducted training where the squad leaders knew how to lead a platoon and one higher-the company. That obviously had a very positive effect on the German Army when it had to expand so rapidly after 1935.

In the course of the war my regiment, on the Eastern Front, suffered extremely high losses. The amazing thing about this was that every man in this regiment who had been wounded tried to get back to his particular unit. That tightened the unit again and gave it an inner skeleton-an esprit de corps.

One of the mistakes that caused the Wehrmacht to lose effectiveness was of a political nature. For instance, new units were formed-the Waffen SS (the combat arm of the SS), the Luftwaffen Felddivision (Air Force field division), and the Volksstrum (home guard)-instead of reinforcing and restrengthening those older units of the Wehrmacht that already had an inner cohesion and combat experience.

How important is history in the education of battalion commanders? What should be the focus of any such study?

I think that the study of history is extremely important. However, I must also say that at this time in Germany we are not doing all that we should, simply because the young people want to distance themselves-they do not want to look at that part of history that I, for example, lived.

I would recommend to you that officers study history to bring forth how soldiers, NCOs, platoon leaders, company, battalion, and brigade commanders turned the battle in the decisive moment by making decisions on their own. In other words, history must be selectively studied to glean tactical lessons. Learning names and dates-these are not important. History must be selectively studied so that valuable military lessons are drawn out.

Are battle simulations and wargames an effective method of training?

Speaking from long experience as a company commander, battalion commander, brigade commander, and general staff officer, I would say the map exercise is the best method of teaching. Without a great deal of effort, many decisions are asked for and the officers, especially the young officers, are forced to formulate their orders quickly, clearly, and precisely. During these exercises all must make decisions and act accordingly. This is done at all levels. Using the terrain model or map exercise, a company commander trains his platoon leaders while the platoon leaders train their squad leaders. The battalion commander uses the map exercise to train the company commanders, the brigade commander to train his battalion commanders, and the division commander to train his brigade commanders.

Many times I have seen someone try to take these “simple” map exercises and turn them into high technology, computer-assisted wargames. My experience with this has been very negative. The technological efforts, the peripheral construction of such a computer game, for example, detracts tremendously from the actual real objective of such a map exercise, which is learning to make decisions on the spot, as is absolutely required in combat.

The most essential part of the map exercise is the officer-in-charge. He must be an experienced officer who knows what he is looking for. He must be an authority. He must to able to ask at anytime, without warning, “Now, you, what do you do?” Every map exercise participant must have imagination and must be able to react immediately. During the final conference, the officer-in-charge must be clear in his value judgment of the decisions made. He must critically examine these decisions and say something about each of them. In the old German Army rarely were these comments complimentary. The Bundeswehr became a bit more polite. The officers and NCOs are more sensitive today than in the past.

Do you conduct these map exercises at every level, beginning with the squad, for instance, and working up through the division, corps, and higher?

For our officer candidates, we use battalion scenarios. He is not a lieutenant yet, but consistent with our method of training two levels up, we put the candidate in the battalion-level situation first. This way he builds a framework of understanding that will enable him to know what he is doing when he begins considering how to employ his platoon. He cannot make logical decisions about how to employ a platoon or company unless he is thoroughly familiar with how his unit fits into the overall battalion scheme.

We put him in a continuing situation in which he faces a threat and must report this because it affects his mission. “Now the communication is dead, Candidate. What are you going to do?” He should know what he has to do as he has been trained to know how his commander would act in this situation. So this is how we teach initiative and how to decide, given mission-type orders. He must take the initiative when the situation changes, but if communications are available, he should report the situation to his leader, so the action can be coordinated. The importance in this connection is that the orders-mission-type orders-given by the commander must tell the subordinate when, where, and which type of operations he (the subordinate) should engage in. What is left to the subordinate is how he is going to do this.

What is the highest level at which these exercises are conducted? Are senior officers-colonels for instance-tested in this kind of exercise?

We use this method at all levels-even today in the Bundeswehr. We use it for training general officers. For example, Gen Wenner, commander of the German Army office, is hosting a commanders’ conference, which lasts five days. He has all his school commanders there, and all his deputy directors from his staff sections. For two and a half days of this five-day period, he conducts a map exercise. There are only generals there. This is our primary method of teaching major principles and tactics to our leaders. They may be generals, but they still need to be trained to be good leaders on the battlefield? We use map exercises to do that.

How do the officers who participate in map exercises present their solutions? Do they prepare staff estimates, etc.?

Someone is going to be asked to present the estimation of terrain; another, the estimation of the enemy or of their own forces. Nobody knows who will be asked to make the presentation. Everyone must be prepared. Everybody must be “living” in the situation. Then the game will be developed. In a division map exercise, the division commander may then ask, “Brigade Commander, what is your decision?” The brigade commander must give his decision on the spot. Then the division commander will ask, “Why did you do that?” The division commander is not calling for the estimate of the situation-he is asking for the decision with rationale. This is not a “decision with excuse.” Think, then make a decision. In a map exercise it is called “thinking aloud.”

In regards to the enormous freedom of action that characterizes German tactics, please discuss this at the level of the junior lieutenant. What is your philosophy of how you prepare the lieutenant for this freedom of action or did you give him as much freedom of action as we perceive?

As I mentioned in describing the training of our generals, we have no differences in principles from lower to higher level training. I am not only a German, I am a Prussian and I keep my Prussian tradition. If you are familiar with Frederick the Great, you know that he had a great impact on training in the Prussian Army. Frederick the Great was famous for saying to an officer on the field of combat, “His Majesty the King did not make you a staff officer because you know how to obey. He made you a staff officer because you know when not to obey.” This principle of knowing when to obey and when to make independent decisions is something that was totally lost under Hitler in the Army of the Third Reich as the war progressed.

I think this principle is again being taught and instilled in our modern army.

In many studies, it has been concluded that because of your General Staff system, you were much more receptive to ideas from your junior officers-even disagreement. A General Staff officer, in fact, was required to express forthright and candid opinions. Is this a correct impression?

Yes, the General Staff officer was raised not so much to criticize, but to give always his open, frank, candid opinion-his honest opinion-to his commanding officer. Even though a commander might have gone so far as to have reached a conclusion that, “This is the way we are going to do it,” the General Staff officer was allowed-encouraged-to speak up. “But, consider this point,” or “This could happen.” That type of criticism was encouraged. The subordinate officer was at the same time expected to have absolute loyalty. Once the commander made his final decision and terminated discussion of the matter, the subordinate officer received the order and carried it out to the best of his abilities.

Is it true that the German General Staff system institutionalized the practice of free and open debate and respect for each others’ roles, sometimes regardless of seniority?

Yes. For example, I think it was an advantage to the Wehrmacht that everybody ate the same food. This was true only of the German Army in my experience. In the Russian Army, there were five classes of food, depending on whether you were a private foot soldier or a general. This illustrates the fact that in the Russian Army it was thought that you had different rights according to rank. In the war, the German Army general recognized his dependence on the private to win battles for him. Our traditions and customs in the Wehrmacht contributed to developing the idea that, “We eat together. We fight together. We act together.” (It is not so strange, then, that there was also an environment where frank opinions could be expressed between respected comrades-in-arms).

When Americans look at mission-type orders and the idea of a fluid battlefleld, marked by rapid maneuver and tremendous initiative by subordinate commanders, one of the flrst concerns is how to coordinate supporting fires so that you don’t hit your own troops. How do you do this?

The danger of hitting friendly troops with your own fires can never be eliminated. In World War II, there was an old artillery joke, which was: “What do I care if it is friend or enemy? The main thing is that I hit a valuable target!”

We keep this problem under control by being sure we have a connection, an interaction, between the battalion and brigade commanders in order to immediately stop friendly fire when it is hitting our own troops.

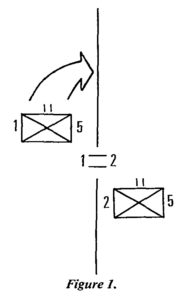

What about control measures, boundaries, and coordination lines? (Here the interviewer drew a sketch similar to Figure 1.) What if the 1st Battalion were to become aware of an opportunity to attack the enemy in 2d Battalion ‘s zone? Say 2d Battalion has no forces in this upper part of his zone now. Whom must 1st Battalion coordinate with in order to cross over into or call fire into 2d Battalion ‘s zone?

What about control measures, boundaries, and coordination lines? (Here the interviewer drew a sketch similar to Figure 1.) What if the 1st Battalion were to become aware of an opportunity to attack the enemy in 2d Battalion ‘s zone? Say 2d Battalion has no forces in this upper part of his zone now. Whom must 1st Battalion coordinate with in order to cross over into or call fire into 2d Battalion ‘s zone?

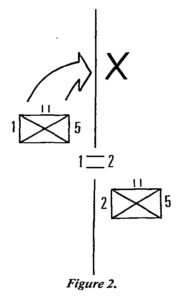

(Col Pestke took the sketch.) If the 1st Battalion has this opportunity, it should take advantage of it. Remember that each battalion commander knows the intent of the brigade commander. He will try to inform the 2d Battalion if he is crossing the boundary, but the most important thing is that he does not miss an opportunity. (Col Pestke drew an “X” in 2d Battalion’s zone of action as shown in Figure 2). Now, if the 1st Battalion enters this zone and is here (at X) I ask you, who is responsible for controlling fires here? The answer is that now it must be the 1st Battalion. We have a principle. Whoever can observe the fire  must control the fire. Otherwise, you miss opportunities. Your response will be too slow. The decision is always made by the one who is able to see the situation right there on the battlefield. Even if the division commander might be smarter, in a situation like that, the lieutenant’s decision might be more important than the general’s.

must control the fire. Otherwise, you miss opportunities. Your response will be too slow. The decision is always made by the one who is able to see the situation right there on the battlefield. Even if the division commander might be smarter, in a situation like that, the lieutenant’s decision might be more important than the general’s.

Now let me say something about these lines and boundaries. These have utility in the defense. But the moment you shift to the offense, such boundaries and lines become impediments. You’ve got to get rid of them.

When you are in the attack, you may set boundaries left and right, but they are coordinating lines, not walls. They are for the initial moves only. They must be very flexible or disappear entirely. Otherwise, they become like blinders on a horse-they hinder more than they help.

What organizational structure do you have for controlling fires?

Out of our war experience, we came to the conclusion to put the artillery on the brigade level. In our brigades there are four combat battalionsarmored or heavy mechanized-and one artillery battalion which is in direct support. So, the brigade commander has his own artillery commander. This artillery commander can also provide the general support by the artillery battalions of the division if it is approved on division level. The artillery commander provides forward observers, captains or first lieutenants as artillery advisors to the maneuver battalions and second lieutenants and sergeants to the company level. In addition, we train our combat platoon leaders, especially in the infantry, to be able to call in and adjust fires. The forward observer has a direct link with his battery commander. But the forward observer gives the order to fire. This can happen almost instantaneously.

When we began discussing fire control we were speaking of boundaries and other control measures. In the American forces, confusion arises from the term “objective. ” Sometimes it is construed as a synonym for “mission.” “Objective” is one of our principles of war, but it also denotes a control measure, usually drawn on a piece of terrain, toward which we direct our attack. The problem arises over the word itself which literally is defined in the English language as an end toward which efforts are directed. If we see the end results of our efforts, fixed on apiece of terrain, then our combat becomes “terrain-oriented.” We become more concerned with the terrain than with the enemy. Would you discuss this?

In German, we have the same control measure. If I speak to you in English, I call it the “objective.” Speaking in German, however, I would not refer exclusively to the terrain as the Objekt. That would imply that the terrain would be the whole object of our effort. In German, the terrain that you designate as objective, we call Angriffsziel or the aiming point for the attack. The Angriffsziel might change in the course of the battle, especially if the enemy is mobile. It is the enemy that is the Objekt of our efforts. The terrain, of course, is extremely important, as we must use it to gain advantage. But the objective of the attack is the enemy. The objective must be to take the enemy out of action, to destroy him, or disarm him. We cannot do that simply by seizing a piece of terrain and holding it. We must be prepared to move continually, wherever necessary, to confuse and disrupt him through a combination of fire and maneuver.

What about logistic support in a fast-moving situation, in the offensive, such as you are describing? Does it become more difficult?

That question gives me the opportunity to say something that I wanted to mention. During war, the most important ability is improvisation. The Russians knew how to do it and still do so today. We also had this ability until the end of World War II. But now, I am afraid we learned too much from the Americans, who want to do everything perfectly.

How do the Soviets cope with such logistics problems?

I think it must be made extremely clear that the Soviets have the ability to make do with almost nothing. For instance, in their ability to get along with a minimum of food and clothing as well as contend with fatigue and severe climate, the Soviets are, in my opinion, superior to us and to the Americans.

They have very robust materiel, be it a tank, artillery, or any vehicle-simple and robust materiel.

Another point is the extremely hard training that the Soviet troops go through. To cite an example, the troops stationed in East Germany generally have no contact with the local population, unlike the American troops in West Germany. They train from early in the morning until late at night. Only on Sunday afternoons are they allowed to go out.

Twice you have discussed the Russians-once when we were discussing command and control and again when we were discussing logistics. As the only one here who has experience fighting the Russians, could you elaborate more?

When we were discussing command and control, I alluded to a certain mental inflexibility-obedience to the death kind of thing. Discipline and obedience can be a negative trait in certain situations, especially if the fear of your superiors is greater than fear of the enemy.

Another weakness which I can relate to you from my war experiences, but which also could be seen in Warsaw Pact exercises today, was a completely rigid and fixed holding of a particular piece of terrain. What I am saying is, hitting the same spot again and again without regard for human life. (I should qualify this by pointing out that it has been 10 years since I have retired from the Bundeswehr and had actual knowledge about what was done behind the “Iron Curtain.” Things may have changed.)

But, this defiance of death is a strength of the Soviets. There is an almost magnificent courage in the Soviet soldier-even the injured man on the ground will still throw his last grenade.

Another very important point is the pride that has been instilled into the Soviet forces because of the victory of what they call the Great Patriotic War or World War II.

Not to be underestimated are the effects of the Marxist-Leninist ideology, which has effectively replaced religion.

The last point is the premilitary training, which starts with very small children and does not end, and with the honor given to the veterans of the Great Patriotic War. For example, for every couple married in a civil ceremony, their first action as a married couple is to visit a memorial to those killed in the Great Patriotic War and place the bridal bouquet at the base of the monument. This respect is not only given to the soldiers who lost their lives in the war, but also to the young soldiers now, who are doing their duty in the armed forces.

At one time during World War II, two German battalions were surrounded and absolutely massacred-including those who tried to surrender. Is this behavior still to be expected in the Soviet soldier?

I would like to answer this question from my own perspective and not make general statements against the Soviets. We Germans were simply not able to hate-to hate as intensely as the other side was. And one must consider the propaganda value (for the Soviets) of the “invader coming in from the West.” The “invader” propaganda was used over and over to play up and keep fervent this kind of hate. If any of you have read Solzhenitsyn you can see that very clearly. The Germans were not able to do that.

Let me make another remark. What the world still thinks of as the “soul” of the Russian people, in my opinion, is no longer there. In the revolution, and at the latest during Stalin’s reign, this “soul” was rubbed out.

The Russian atrocities committed, for example, in my home town in West Prussia, can’t be understood by anybody who wasn’t there. When one compared those with the atrocities committed by the Nazis, I would say that the Soviet actions were at least as unthinkable and inhuman.

The best illustration is that people who were living in what was then East and West Prussia moved, under very dire circumstances, toward the English and American troops, because they knew the Russians were after revenge. This is evidenced by what happened when they did catch up with the civilian population.

How is it possible to better learn the Soviet soldier’s mind set-how he thinks and how he is likely to react in combat?

To say anything about the mentality of the Russian soldier today is very difficult. In my opinion his way of thinking is best illustrated in Russian war literature-war novels. These are not simply war histories or after-action reports. These are personal accounts-war novels-written by Russians who were in the war. They are extremely personal. You can see how the individual soldier suffered and how he admired the party. It goes down to the company and platoon level. The stories are incredible. If you compare them with us in the West, then we are on the decline like the Romans, because of our softness. The Soviets are still hungry and tough.

These books have given me more insight into the Russian soldier’s mind-how he acts on the battlefield, from the leader to the soldier-than any other literature or report.

As you know, the Soviet Union is composed of many almost autonomous nations. The Soviet Union does not have the capability of integrating its people like the United States of America. Each member of a nationality remains within his national capsule-a Lithuanian is a Lithuanian, a Georgian (from the Caucasus) remains a Georgian.

One can notice, however, two opposite developments. One is an increasing Russianization because of the educational system. This Russianization by education is affecting only what they call the intelligentsia-the upper crust of the population. Another development, which is seen as dangerous in the Soviet Union, is that non-Russians in the Soviet Union, outnumber the Russians. In connection with this, I think that one can expect a new awakening of nationalistic sentiments of the many nations within the Soviet Union. People who attended the 1980 Olympics in Moscow reported an awakening of pride in the Baltic states, as well as in the Asian states-an awareness of heritage. So we not only have an increase of the ethnic national consciousness, we also have an opposition to the [Russian] state developing.