A Brother’s Journey: Five Decades to the Story of a Lifetime

By: Kyle WattsPosted on March 15, 2023

On Saturday, Oct. 21, 1967, David Jensen was working at a caterer’s office in Hales Corners, Wis. As the 18-year-old prepared orders for the coming week, the office owner entered the room.

“Dave, you need to go home.”

His terseness caught David off guard. He appeared somber and was obviously not playing around.

“Well, no,” David replied. “I can finish up this order, at least.”

“No, Dave. You can’t linger. You need to go home, now.”

He gathered his things and returned to his parent’s house. The staff car from the local Marine Corps recruiter’s office sat in the driveway. A recruiter’s presence was not unusual. David had known them since he was 12, the first time he entered their office with his older brother, Alan. Alan was a Marine, and David was determined to become one too.

David walked through the front door. A major and first sergeant in dress blues sat in the living room with David’s parents. A Bible lay open on the coffee table. Tears poured down his mother’s cheeks. His father approached him.

“David,” he faltered. “Alan is dead. He was killed.”

David moved toward the recruiters. His gut reaction came out as anger.

“You got proof? Where’s his dog tags?”

The Marines sat him down and described what they knew. Alan was killed in Vietnam on a recon patrol a few days earlier. Due to the intensity of the firefight, Alan’s body had to be left behind. Marines were still working to recover him.

The recruiters left after David settled down. He sat with his family in a group hug. What now? Nothing would ever be the same. His big brother was gone.

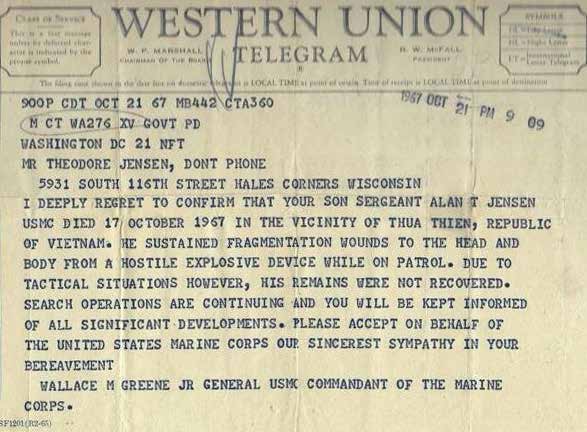

A Western Union telegram arrived the following day, officially confirming the news. One of Alan’s Marine buddies traveled to the Jensen home from Detroit. He stayed with them as they waited for further news, helping craft letters to Alan’s unit in Vietnam, and telling the family about Alan’s first combat deployment, where they served together in 1965. Finally, nearly a week later, more news arrived. Marines had recovered Alan’s body. He was coming home.

Alan’s remains arrived in Milwaukee, Wis., on Nov. 7. When his father arrived at the funeral home, the director informed him the funeral would require a closed casket. His father asked to see the body, but the director refused. His father insisted and witnessed firsthand the horrors of the war, and how unkind the enemy could be to an American body.

On Veterans Day, a police motorcade brought Alan to General Mitchell Field in Milwaukee to be transported to Arlington National Cemetery. The family flew to Washington, D.C., and prepared for his interment the following week. David watched his brother descend into the earth among the seemingly infinite rows of identical headstones. How could this be real? He reflected on his brother and decided, now more than ever, he wanted to follow in Alan’s footsteps.

David and Alan were the two boys in their family of six. Alan was the oldest child. David arrived seven years later, with a sister between them, and another sister after him. From his earliest memories, David always considered Alan his role model.

“We grew up hunting, fishing, trapping,” David remembered. “One of his friends told me once on a camping trip that Alan had berated him, telling him he didn’t even have what it took to be a Boy Scout. Even back then, Alan was a gung-ho kid, kicking ass and taking names. He taught me how to shoot, he taught me about girls. He was a Marine!”

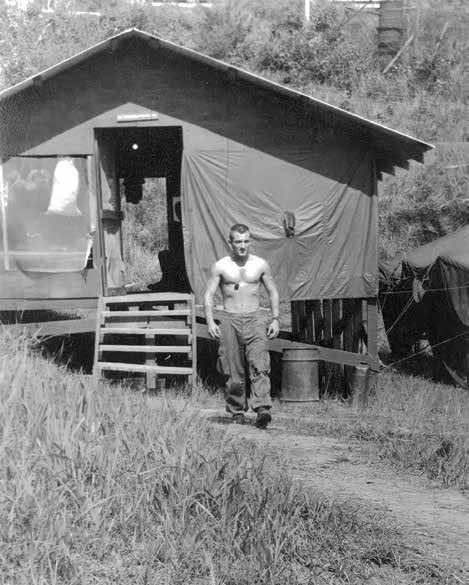

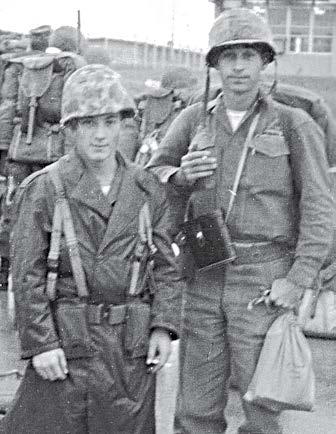

When Alan decided to enlist, David begged to sign his name on the papers alongside him. The age gap between them, however, meant David would have to wait. Alan shipped out in 1961, serving initially as a machine-gunner with “Golf” Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines. He worked his way up the ranks and became a section leader. He deployed to Vietnam where he transitioned to 3rd Recon Battalion and began running patrols behind enemy lines.

David received Alan’s letters and waited for his brother to come home. Alan finally returned during the summer of 1965. He left active duty altogether when his contract ran out that August. David was elated. The brothers returned to their usual outdoor activities. Now 16 years old, David was thrilled to show his brother how much older he’d become and how much closer to beginning his own enlistment in the Corps. Alan encouraged the decision.

“I remember he told me if you were going to be a Boy Scout, you’d better be an Eagle Scout,” David said. “And if you’re going to join the military, you’d better be a Marine.”

Alan tried settling back into civilian life. He got a job and even purchased 16 acres in northern Wisconsin with one of his Marine buddies. Something was off, however. David recognized the change. Alan seemed angrier. Neither brother had ever been the holiest of kids, but now Alan’s fuse proved extra short. One day while driving down the road, the car in front of them stopped at an intersection. Alan’s temper exploded when the driver took too long to drive on. David watched in awe from the passenger seat as Alan exited their car in the middle of the road, walked up to the vehicle in front of them, and yanked the driver out onto the street to fight.

Finally, in early 1967, Alan decided he could not take the civilian life anymore. He told David and the rest of his family he had to go back in the Marines. He could not see a good future for himself without the Corps. Alan contacted another Marine he’d served with on his first tour, who was now a recruiter in Louisiana. The recruiter told Alan that he could get him back in, but he’d lose the rank he had when he was discharged. Without hesitation, Alan jumped in his car and drove south to sign the papers. As Alan headed off again, David’s father took him aside.

“I was pissed,” David remembered. “My brother had such a profound influence on me. My father told me, ‘This is what he has to do. A man has to do what a man has to do.’ I was disappointed, but I had to understand.”

Alan reenlisted in February, and by May was already back in Vietnam. Now with 1st Force Reconnaissance Company, Alan once again operated on clandestine patrols behind enemy lines. By the time of his death that October, Alan had achieved the rank of sergeant and was an assistant team leader in the company.

David carried on with his plan to follow in his brother’s footsteps. His parents held reservations about him enlisting and they worked with recruiters to guarantee David would not see combat. He enlisted in March 1968 and served with land and carrier-based maintenance squadrons servicing jet engines. He tried to go to Vietnam but was refused. The Corps decided one son was enough for the Jensen family. David left active duty after his initial contract ended, then returned to service later in the Marine Corps Reserve as a Huey maintenance technician. He exited the Marines altogether in 1977.

In 1982, David learned about the newly dedicated Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. He had visited Alan’s grave at Arlington several times but now hoped to make the journey again and visit “The Wall.” For years, life’s obligations delayed the trip. Regrettably, David’s father passed away in 1985 before he had the opportunity to visit the memorial. Finally, in 1987, David flew to Washington with his mother and sister.

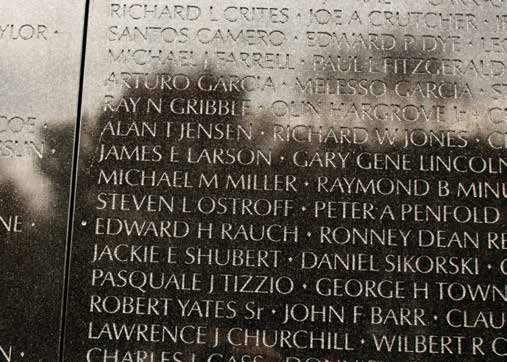

David entered The Wall’s pathway near the Lincoln Memorial. The Wall grew beside him as he searched for panel 28E. The sea of names blurred together. Others walked the path beside him. Some wept as they placed flowers at the base of a panel. Some stood in silence with hands raised over a name on the wall. As The Wall began to shrink once more, 28E came into view. David traced his finger down the left side counting lines. When he reached 26, Alan’s name surprised him, first in that line at the left of the panel. David paused with his fingers touching the name above his head. Below Alan’s name, David’s reflection filled the polished granite. Names continued to infinity left and right. Other passing visitors moved as a blur through the reflection. In that moment, David felt his brother again, just the two of them, there on The Wall.

“Looking at the big picture of over 58,000 names on that wall, that meant there were a lot of other people who had to go through these things like my family had to go through,” David reflected. “I realized there were so many other brothers or sisters out there with someone’s name on the wall. I was not the only one.”

David flew home to his wife in Colorado. Recounting the trip for her felt like reliving his brother’s death 20 years earlier. Memories of his parents’ house and the recruiters’ car in the driveway rushed back into his brain. They broke down his manly facade and forced him to confront a painful reality he’d long tried to ignore.

“I think I have more healing to do.”

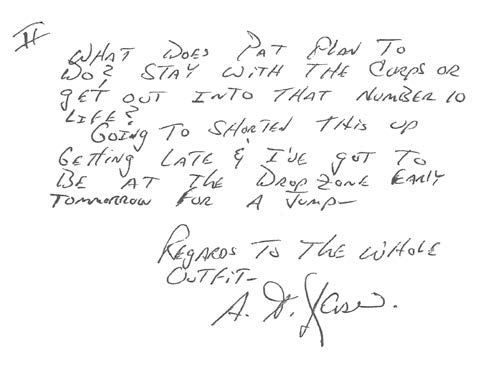

David embarked on a journey to discover what happened to Alan, and who he was as a Marine in combat. He reviewed letters his family had received 20 years earlier. Alan’s commanding officer, executive officer, platoon commander, and other fellow Marines responded to the family’s requests for more information in the wake of Alan’s death. Their letters painted a basic picture of the patrol where Alan died. David progressed slowly at first as the Marines directly connected to Alan’s final patrol proved difficult to find.

He finally achieved a breakthrough in 1989. An ad appeared in Leatherneck Magazine for an upcoming Force Recon Association reunion in Dallas, Texas. David explained who he was to the contact listed and received an invitation to attend. When the time came, David traveled to Texas, eager to learn what questions might be answered.

David discovered how small a world the Force Recon community lived in. Virtually everyone at the reunion either knew of or served with his brother. Marines who served with Alan on his first deployment in 3rd Recon Battalion told David of their shadowy missions in rubber boats off the Vietnamese coast in 1965. Many others told him stories from 1967, leading up to Alan’s death. David met Stan Chapman, a Navy corpsman. Chapman described his painful memories of caring for Alan’s remains once they were recovered, and his presence in the room when a group of Marines were summoned to positively identify him.

The patrol where Alan died was something out of the ordinary for Force Recon. A team of 17 Marines, dubbed Recon Team Petrify, went into an area swarming with North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers. The enemy presence was normal. The size of the patrol was not. Petrify consisted of more than double the number of Marines on a standard mission. Every member of the team was wounded. One other Marine besides Alan was also killed. A company-size “Bald Eagle” reactionary force was called to rescue Team Petrify. Multiple helicopters were shot down trying to extract them.

David arrived back in Colorado armed with information and contacts he’d never dreamed of making. Several weeks later, David found a package on his front doorstep. He cut open the box and removed an unlabeled cassette. A small note accompanied the tape, penned by one of the men he met in Dallas.

“David, I think you’ll find this interesting.”

He hustled to a cassette player and inserted the tape. The speaker crackled to life with pops and static as it turned from reel to reel. A grainy, scripted voice broke through in a southern accent.

“These interviews are narratives of a recon patrol originally inserted to set up an observation post in Elephant Valley northwest of Da Nang. The location is the Command Post, 1st Force Recon Company, 1st Marine Division, Quang Nam Province, Da Nang TAOR, Republic of Vietnam. The day is 23 October 1967. The subject is Recon Patrol Petrify. The classification of these interviews is secret until downgraded by proper authority.”

Different voices followed each other in succession. The interviews had been done in Vietnam mere days after Petrify returned to base. When they were recorded, David’s family had only recently been told of Alan’s death, and his body had still not yet been recovered. The tape played through interviews of four patrol members, all describing every detail they could remember surrounding the patrol, Alan’s death, and their terrifying extraction. David rewound the cassette and played it again. He still could not believe what he was hearing. Two years into his search, Alan’s story was finally coming into focus.

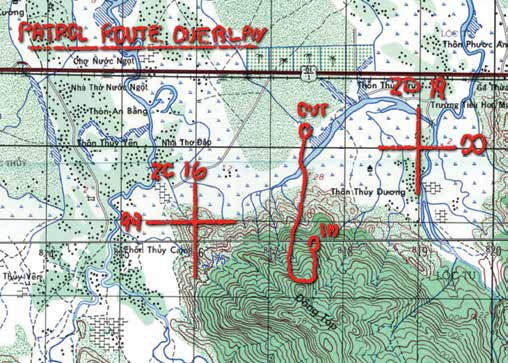

On Oct. 14, 1967, leaders from 1st Force called for volunteers to go out on a special mission. Another Recon team had inserted on a hill called Dong Top Mountain. In less than 24 hours, the Marines faced continuous enemy contact, taking a severe beating. First Force was tasked with relieving the team and continuing the patrol where they left off. Due to the known enemy presence, officers wanted a larger team and asked for volunteers. Seventeen Marines were thrown together into Team Petrify. Alan volunteered for the mission and acted as one of the senior members.

Petrify inserted the following day, picking up where the previous team left off. For over 24 hours they moved through the jungle around Dong Top without contact. Signs of the enemy, however, were omnipresent. In the afternoon of patrol’s second day, the team’s machine-gun crew opened fire when NVA soldiers rounded a bend in a trail. One soldier dropped dead, and a second enemy fell wounded. The two Marines advanced toward them. Grenade rounds launched from a M-79 grenade launcher suddenly exploded near them, driving them back.

Seemingly out of nowhere, Alan came sprinting through the underbrush. Screaming and hollering and firing his rifle, he drew enemy attention off the machine-gun team, allowing them to move to cover. When the M-79 rounds ceased, Alan ran forward to collect anything he could find. Blood and body parts covered the trail, but both NVA were gone. Alan and the gun team rejoined the main group. Alan exposed himself to more enemy fire to help the rest of the team break contact. The team harbored in the thickest brush they could find. Dusk settled into the defense with the Marines, and the last rays of sun faded to black. The night passed at an excruciating pace. Small arms fire punctuated the silence in all directions as the NVA scoured the mountainside.

Dawn of Oct. 17 brought little relief. At noon, the team decided they had to move. They located an area filled with huge rocks and set up their defense once more. The position offered ample cover and concealment. Unknown to the Marines, however, the NVA occupied a ridge above them. Rustling voices increased in all directions around Petrify. Suddenly, around 4 p.m., machine-gun fire raked the position and grenades rained down.

The opening enemy barrage devastated the Marines. Within seconds, Alan was dead. Two bullets ripped through his chest, and grenade fragments hit his head. LCpl Jerry DeGray fell also, shot twice in the head. Several other Marines were seriously wounded, and every member of the patrol suffered at least minor shrapnel wounds. Despite the damage inflicted, every surviving Marine returned fire. A ferocious roar enveloped the mountain as the Recon team battled with NVA surrounding them.

Huey gunships arrived on scene within 30 minutes. They worked over the ridge and surrounding jungle. An observation plane arrived, armed with an assortment of jets behind him. As the first flight of gunships expended their ordnance, jets took turns racing in with bombs. A second flight of Hueys arrived, pumping rockets and machine-gun fire into the jungle. A CH-46 approached at dusk to attempt an emergency medevac but was shot out of the zone. All the air support available seemed only to kick the hornet’s nest harder. Seeing the team’s predicament, officers called for a reaction force to get Petrify out. A company of grunts deployed to the base of Dong Top at dusk and began the long trek up the hill.

Helicopters arrived back over the team shortly after 7 a.m. the next morning. Hueys once again pounded the ridge and jungle floor. Even as more gunships and jets expended their ordnance, enemy fire struck three choppers attempting another extraction and forced them out of the zone.

Finally, around 9 a.m., the reaction force arrived on the hill. The grunts established their defense and worked toward the Recon team. A single squad finally battled through to reach them two hours later. Because of the amount of gear and wounded to get out, they split the patrol in half. The first group, with the most seriously wounded and the body of LCpl DeGray, moved out with the infantry squad. Nine Recon Marines remained behind with Alan’s body.

The firefight swelled as the morning wore on. NVA soldiers appeared from every direction with grenades, mortars and machine guns, hell bent on stopping the grunts and wiping out Petrify. After several hours, the remainder of the team still among the rocks decided their position was untenable. The grunts would not make it back. The team would have to make it to them.

They placed Alan’s body on a stretcher and moved out along a trail. The battle raging between the reaction force and NVA increased in ferocity as they neared the grunts’ position. A fever pitch of explosions roared through the jungle. Suddenly, tracer rounds crisscrossed the trail all around and among them. The Marines carrying Alan’s stretcher dropped his body and brought up their rifles. On one side of the trail, less than 20 meters away, a group of NVA fired machine guns and mortars. On the other side of the trail the same distance away, grunts fought back. The recon team hit the deck, trapped in the crossfire between the opposing forces. NVA grenades soared over and landed amongst the team. Marines scattered in all directions searching for cover, while Alan’s body remained unmoved on the stretcher. He lay less than 15 feet away from the rest of the team, but the enemy fire was so intense they could not move back to him.

The grunts advanced far enough to reach the team. They worked together to suppress the NVA, now mere feet away. One infantry Marine was killed in the fight and fell ahead of the rest, a stone’s throw away from Alan’s body. Two squads made multiple attempts to recover Alan and their own casualty but failed. Finally, the commanding officer on the hill directed all Marines to get back to the main line. They had to move off the mountain before the NVA overran their position.

A second reaction force arrived to relieve the first one and evacuate Dong Top. The going was incredibly slow as Marines worked down the steep terrain. They reached the bottom of the hill at dawn the following morning where everyone moved back to Da Nang. Two Marine infantry companies plus the heavy recon team lacked the numbers and firepower to overcome the NVA on Dong Top Mountain.

The contents of the cassette tape painted a vivid picture of the events surrounding Alan’s death, but for David, it was still incomplete. The interviews took place before his brother’s body was recovered. He remembered the funeral director refusing to open the casket at Alan’s funeral, and his father’s face after he’d seen the body. He remembered the words of the corpsman he’d met at the reunion when David insisted he tell him the details of what the NVA did to Alan’s body. The old Doc described the terrifying details of Alan’s mutilated corpse, and his disgust for the bastards who could do such things.

Over the next few years, David filled in Alan’s story. He attended two more Force Recon reunions. At one point, he met in person with a member of Team Petrify who was one of the seriously wounded on the patrol. David gave him copies of the cassette tape interviews, which the Marine never knew existed. David realized that because of his research, he actually knew more of the big picture surrounding the patrol than someone who was there on the ground. In less than five years following his visit to The Wall, David felt he’d accomplished his mission. His brother’s loss still tore at his heart. In some ways, even more so now than before, given the tragic details. Pride, however, overcame the grief. Alan was a loved and respected teammate within the recon community. For his actions on the patrol, Alan posthumously received a Bronze Star Medal with Valor device. As David closed the book on his research, he knew his brother’s death was not in vain and was remembered by more than just him.

Nearly three decades passed before David reopened the book, beginning a second chapter on his brother’s death. In 2018, David learned the name of the reaction force grunt killed in the same place as Alan. Lance Corporal Howard Ogden went down on Dong Top Mountain less than 50 feet from where Alan’s body was left. Though Alan eventually returned home, Ogden’s body disappeared. His status was officially listed as Killed in Action/Body Not Recovered. He posthumously received a Silver Star for his role in the battle.

David located Ogden’s memorial page on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund Wall of Faces.

“Thank you, Marine,” he wrote in the comments. “You sacrificed your life in recovering my brother’s body. Sgt Alan T. Jensen, who in his first enlistment was also in 2/7. God Bless you.”

David received a surprising response from a lady named Maggie Ardery. Maggie was Ogden’s older sister. Just like David, Maggie devoted considerable effort to discovering what had happened to her brother on Dong Top. Maggie’s journey, however, continued to the present, as Ogden’s case remained active at the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing In Action Accounting Agency (DPAA).

David called Maggie and learned of her quest to see her brother return home. He sympathized and understood her pain in ways most people never could. He committed to help Maggie with her efforts and resumed his own journey from a different perspective.

David learned of the Virtual Vietnam Archive, hosted by Texas Tech University, where he located the command chronologies of other units involved in Team Petrify’s extraction. The documents revealed a broader picture and told the story of Alan’s recovery a week later.

Marine Observation Squadron (VMO) 2 and Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron (HMM) 265 provided the helicopters that forced the enemy back and attempted the emergency medevacs of Team Petrify. Their efforts came at a cost. Enemy fire shot up one CH-46 so badly it was forced to crash land at the base of Dong Top. Another Huey gunship suffered similar damage and crashed nearby. Part of the reaction force sent to the mountain peeled off to secure the area around the downed aircraft. Despite the crashed choppers and enemy mortar fire into the crash site, no Marines were injured.

The first helicopter from HMM-265 attempting a medevac of Petrify’s wounded on Oct. 17, however, did not fare so lucky. When the CH-46 arrived at dusk, Cpl Howard Morse lay on his stomach peering down through the “hell hole” in the center of the bird’s belly as a hoist lowered painfully slowly to the ground. NVA on the ridge opened fire. Bullets passed through the thin aluminum skin of the helicopter. One found its mark and entered Morse’s abdomen below his body armor. The pilot aborted the extraction, but it was already too late. Morse died in the hospital eight days later. To quantify the air wing’s efforts over the two-day period of Petrify’s extraction, VMO-2 reported that their Hueys fired 446 rockets and 54,500 rounds of machine-gun ammo.

Golf Co, 2/7, formed the initial reaction force to rescue Petrify. The battalion also provided a reaction force to rescue the recon team that Petrify was assembled to relieve. On the same day Alan was killed, in a separate area of Dong Top Mountain, another company from 7th Marines deployed to rescue a third surrounded recon team. In the end, the jungle into which Team Petrify walked swarmed with an estimated 800 NVA, and a full battalion of Marines was needed to get all the recon teams out.

Several days later, 2/7 returned to Dong Top to search for Alan and Howard Ogden. The battalion’s casualties mounted once again as grunts spread across the hill. On Oct. 24, Golf Co reached the area where the Marines went missing. Through the jungle, they saw a desecrated body tied to a tree. Mortars, grenades, and machine-gun fire greeted them as they moved to recover the body. The grunts withdrew, unable to force their way through. A squad returned the following morning to find the NVA moved out of the area overnight. They cut the binds from the tree and moved the body back to the command post. They immediately identified the remains as a recon Marine. Ogden was nowhere to be found.

David worked with Maggie to locate Marines who served with her brother, the same way others had helped him locate recon Marines who served with Alan. They contacted veterans from 2/7 and spoke with Marines who fought on Dong Top alongside Alan and Ogden. Maggie included David on all her correspondence with the DPAA. In July 2019, a DPAA team went to Dong Top Mountain looking for information on Ogden and other missing Americans. They searched the area, but did not excavate, planning to begin those efforts at a later date. Regrettably, all DPAA field activities abruptly halted with the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. As of this writing, the excavation on Dong Top has still not been rescheduled.

In September 2020, David and Maggie met in person at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Angel Fire, N.M. Though they had been acquainted barely more than a year, they regarded each other as adopted siblings and embraced as if they were reuniting with a beloved old friend. They purchased memorial bricks engraved with the names of their brothers to be included in the memorial walkway. As Alan’s brick was lain down along the sidewalk, memories flooded David’s consciousness. His father’s face appeared as he told David of Alan’s death at their childhood home. David’s own face appeared, reflected in the memorial wall in D.C., as he determined to begin his journey. Over five decades of discovery led him here. He met many people who helped him along the way. He gained a new sister, one of those other siblings like him that he’d reflected on at the wall years before. He’d never imagine someone else out there might be enduring the same grief as he, losing their brother on the same mission and in the exact same place as his own.

David learned the man he knew as his big brother was no different to the Marines he served with; still a role model, a leader, and a friend. The time had still not come to close the book on the story of Team Petrify and Dong Top Mountain, only another chapter was set to close. Howard Ogden still needed to come home. Maggie’s family deserved the closure. As for Alan’s story, David felt whole. The healing he sought was finally found.

Author’s note: David’s journey, and this story, could not have happened without the help of many people over the five decades since David set out to learn what happened to his brother. David would like to recognize the following individuals. Semper Fi, and thank you!